In Photoworks Issue 5, David Campany looked at the multiple layers of Helen Sear's work

In William Henry Fox Talbot’s early treatise on photography The Pencil of Nature there is a humble image of a piece of fabric. Talbot placed black lace directly on to sensitised paper and exposed it to the sun. The lace appears white on a dark background. It doesn’t look like a negative, since we are as familiar with white lace as black. It doesn’t look like a cameraless photogram either – the flat fabric is so well rendered by the simple technique. Talbot’s term for the process was ‘photogenic drawing’, connecting it the idea that the photographic image was a mechanised stencil of the world. His image is simple and fascinating. The not yet standard mechanism of photography takes as its subject a piece of not quite standardised, hand made lace. It is scientific, distant and cool. It is also intimate, close and tactile. In this it embodies the paradoxes that run right through thinking about photography from its beginnings to the present. A photograph is all about surface yet it appears to have no surface. It is formal and systematic yet it brings out the particular in things. It is stoic and removed yet the light that touches the object then touches a receptive surface.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

Helen Sear has been making photographic work as an artist for fourteen years. Her output is remarkably varied but much of it makes a virtue of the qualities we see Talbot’s picture. Questions of touch and the experience of surface are central, as they are for many painters coming to photography. Inside the View also involves the presence and absence of lace.

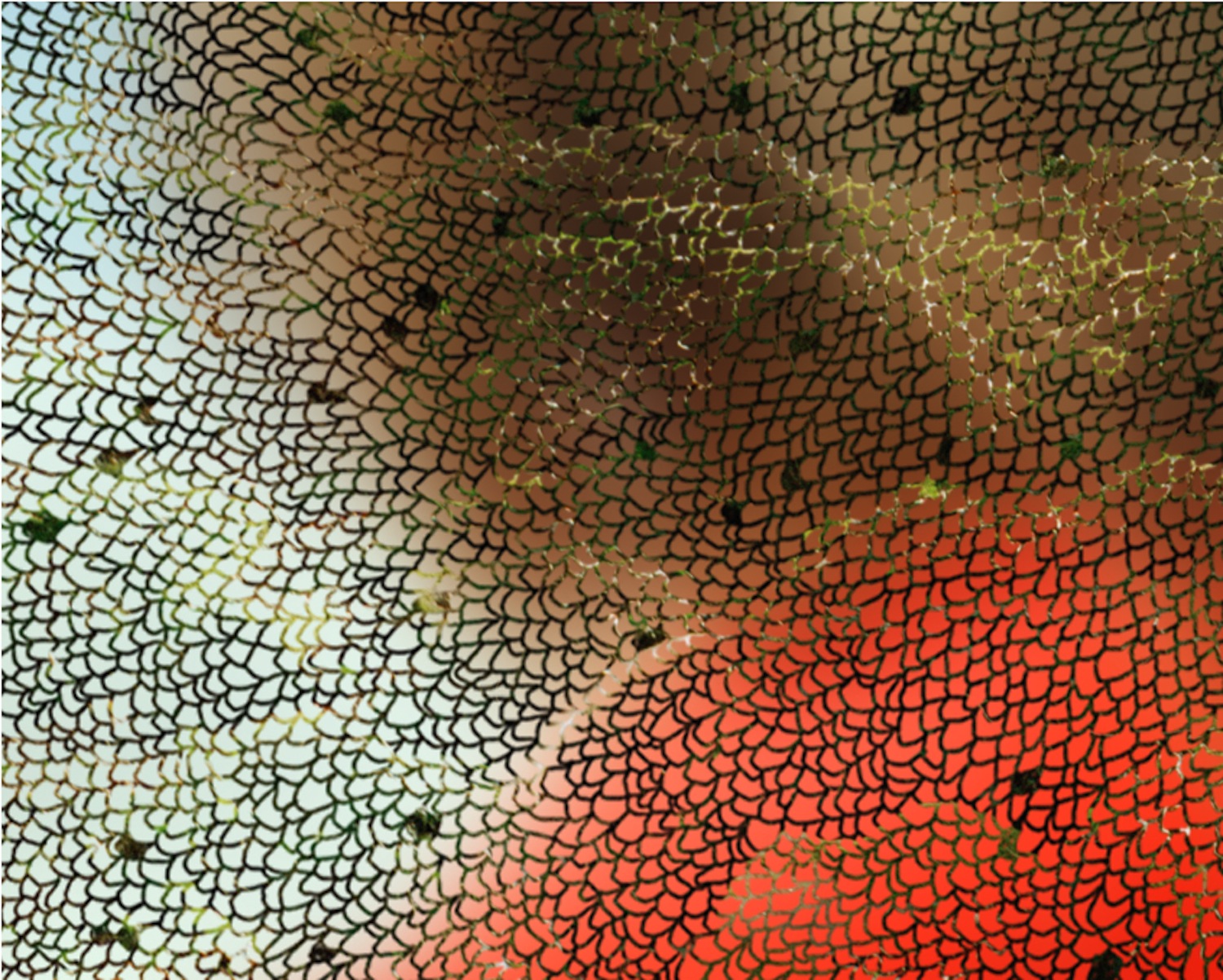

Sear is one of photography’s foremost innovators. For her the medium is one of magic as much as realism. It is never pure, fixed or entirely knowable. Each new series presents a new set of challenges that offer up her fascination with craft and our habits of looking. Inside the View is a set of combined images. On one level they contribute to the long history of montage. Two images are brought together to generate a third meaning. Here a portrait and a landscape are combined. But there is something more complicated. Sear also produces a third image out of her method. The two photos are brought together on a computer screen in Photoshop. Onto the image of a woman’s head, Sear ‘draws’ a lace-like network of lines in which emerges a photo of a landscape. In painting and drawing the line is usually there to form an image. In Sear’s work the line is the image. The network becomes a veil to look at and to look through. It is difficult to tell if it is really ‘there’.

The recent influence of painting on photography has been dominated by a kind of classical imitation. Photographic artists and documentary photographers in particular seem to wish to quote from painting, often in pursuit of credibility or knowingness. Think of the ex-battlefield photographed like a Constable; or the inner city portrait posed like a Vermeer or a Chardin; or moments of human uncertainty alluding to Manet’s tableaux of the everyday. In general photography borrows from artists and artworks that allow it to retain its well-established modes of realism and transparency. But Sear shows there are other relations photography may take up to the painterly.

Certainly Sear engages with the pictorial, with genres as they have been handed down and modified. In addition her painterliness also emerges in the image as a worked surface. It is often thought that photography lacks surface, that its picture plane is intangible. This is why pictorialist photographers in the early part of the last century wanted to work with hand brushed emulsions. It is also the reason why the modernists that came after compensated for the sheen of their prints by obsessing over texture in their subject matter (think of the crumbling walls, sand, bark that dominate the work of Edward Weston, for example). Sear is interested in touch and surface but in a different mode.

Inside the View involves two screens. Firstly there is the computer screen on which the lace effect is drawn. Obviously the hand doesn’t touch the screen. Sear draws by way of an pen on an electronic tablet. It is an abstracted mode of drawing with which we are all becoming familiar now. We move our hand in one place – using a mouse – and its indexical effect is felt somewhere else. Hand and eye work together.

Within the multiple layers of Sear’s art we face the complex questions of work and invention. The innovative labour of image craft is central here. She does things few others do with the medium. Each new body of work is a separate challenge, for herself and for the viewer. It is a restless process of intellectual risk, aesthetic demand and technical experiment. Making Inside the View was painstaking. Forming the lace image was immersive work that demands an inner intensity. It is slow and involved. Perhaps this is why Sear takes as her subject women contemplating landscapes. A landscape is always in some sense an mindscape, not least when we are ‘immersed’ in it. But the women wee see are not strictly ‘in’ these spaces. Sear has combined images to give that impression. The effect is seen spatially but constructed on our mental screen, so to speak. It is we who are “inside the view”.

[/ms-protect-content]

Published in Photoworks Issue 5, 2005/6

Commissioned by Photoworks

Buy Photoworks issue 5