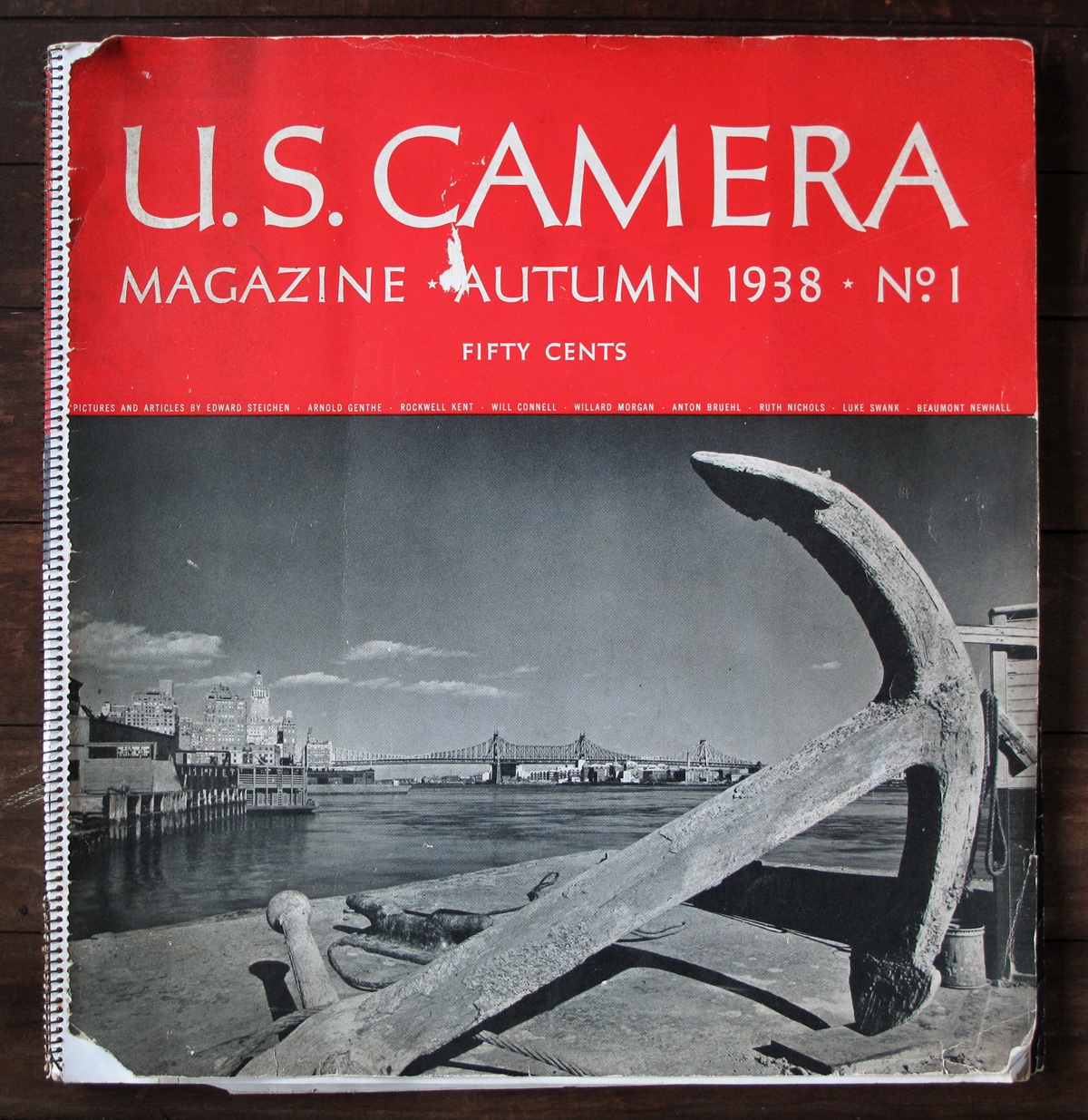

Late last summer, buried deep in a New England barn that had been converted into a cluttered antique shop, I spotted a dusty old copy of the defunct magazine, U.S. Camera.

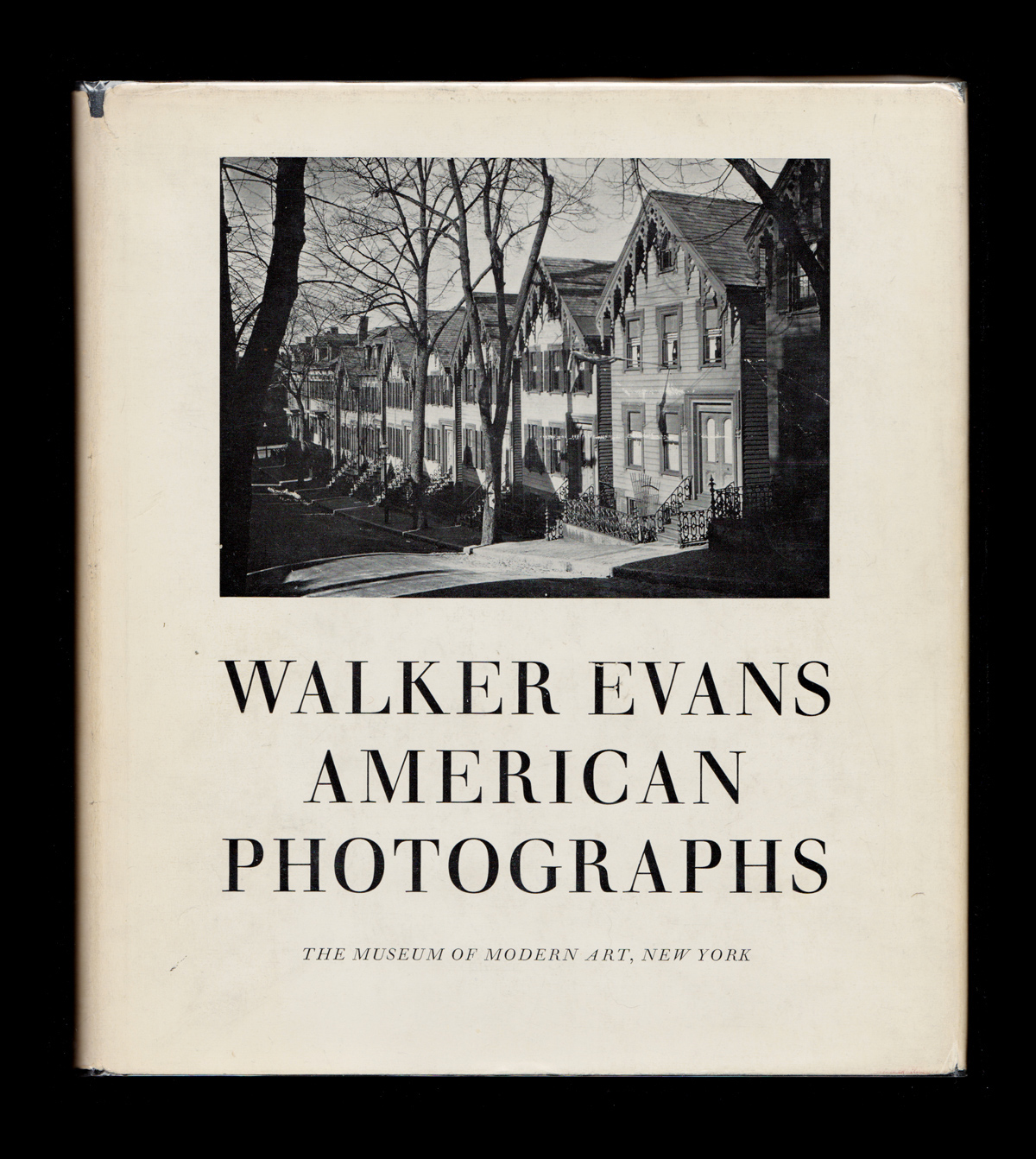

Looking closer I realized that it was, in fact, the magazine’s inaugural issue – Autumn 1938 – and amongst technical reviews of enlargers, advertisements for cameras and so on, it included an impressive line-up of contributions by Edward Steichen, Edward Weston, Eliot Porter, Beaumont Newhall, Arnold Genthe, ‘London’s Bashful Boy-Wonder’ Norman Parkinson, and more. In its back pages, I was even more thrilled to discover a short review of the then newly-published American Photographs, by Walker Evans. Unattributed, but presumably written by the magazine’s founder and editor Thomas J. Maloney, it insightfully stated in its opening paragraph, ‘[E]veryone interested in American photography should read this book. This is a case where read applied to pictures is better terminology to see.’

Given the infinite variables and variations within the genre, as well as the ever-expanding design, printing and publishing possibilities now available to photographers, answering the question ‘What makes a good photobook?’ today is ‘a large order – read at all literally, the phrase would be an absurdity’ (to appropriate a quote from Robert Frank’s 1954 Guggenheim Fellowship application for what became The Americans, most often cited as ‘the greatest photobook ever published’). But for me – and as the relatively recently compounded term ‘photo / book’ itself suggests – Maloney’s review reinforced the notion that what makes a good photobook often comes down to the delicate balance between the two distinct acts we engage in when we dive into the pages of such a publication; namely, between seeing and reading.

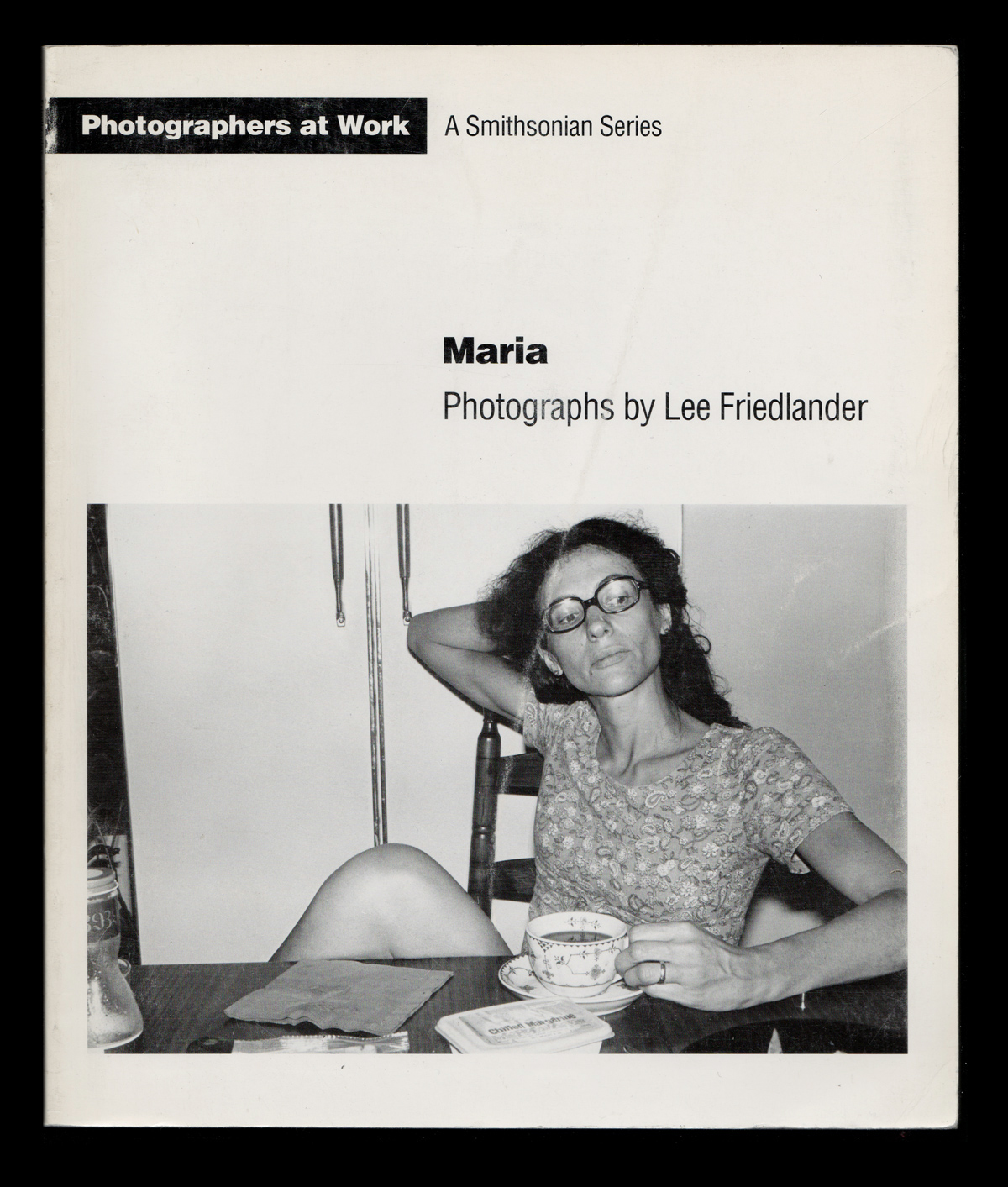

In Maria – published in 1992 as part of the Smithsonian’s Photographers at Work series, and despite its modesty, one of my all-time favourite photobooks (a battered copy of which I treasure like no other) – Lee Friedlander states, ‘I love the work of other people that I first saw in books, like Walker Evans’s or Robert Frank’s.’ ‘There’s so much information,’ he continues, ‘that often I don’t see until the fifth reading or thirty years later. I can pick up Walker’s book American Photographs today and see something I never saw before – and I’ve owned that book for over thirty years…so I think that books are really a wonderful way to show photographs. I can go back and re-read things. “Oh shit, I didn’t see that before.”’

In this particular interview, Friedlander seems to flip back and forth between the acts of seeing and reading quite casually, intimating that when it comes to photobooks they are so integrated that, in a sense, they are interchangeable. But if we look closely, there are vital differentiations to be made between them. What we see in a photobook are the photographs themselves, and the totality – as well as the ambiguity – of the information that they contain; what we read, whether it takes us thirty minutes or thirty years, is this same information, but distilled – through the interplay between the photographs, through our experience and imagination, and through the relationships that are built, asserted and insinuated by the structure of the photobook itself. It is here, in the precision of this distillation, imagination and structure – in the filtering, editing, sequencing, positioning, pacing, shaping, shifting, sculpting and interweaving of this overwhelming plethora of information – where the authorship and specific artistry of the photobook lies.

But most importantly, because of the beautifully ambiguous nature of the photographic medium itself, no matter how precise author’s efforts are in these matters, the power of the photobook is not purely determined by their own ingenuity, but also by the their understanding of – and faith within – the reader’s own interpretive and imaginative skills beyond it.

As the U.S. Camera review of American Photographs progresses, it becomes clear that such confident surrenders to both photographic ambiguity and the intelligence of one’s readers weren’t always fully appreciated when it came to the photobook:

‘The Museum of Modern Art has given [the book] a severe, or perhaps ‘twere better to say virginal, format…The photos are printed on the right-hand page, the left unsullied except for a page numeral. Though the treatment is in keeping with the book, the reader would probably prefer to have a few of the ordinary aids to easy enlightenment such as captions, and possible footnotes with the pictures. There’s hardly a picture in the book that wouldn’t be a better picture with a limited amount of text, and though it’s obvious that the author and publishers felt just the opposite, there is still room for the statement.’

Yet nearly eighty years later, the ‘virginal’ format described above has become one of the definitive formats – if not the definition, in a more general sense – of the contemporary photobook. We are drawn to photobooks, and into them, by their sparse, uncertain, enigmatic nature; we crave and celebrate the complexity and interpretive potential of their individual photographs, and relish the friction and fusion that occurs when those images are carefully placed for us amongst one another, without the support of ‘ordinary aids to easy enlightenment’ such as texts, captions, footnotes or otherwise.

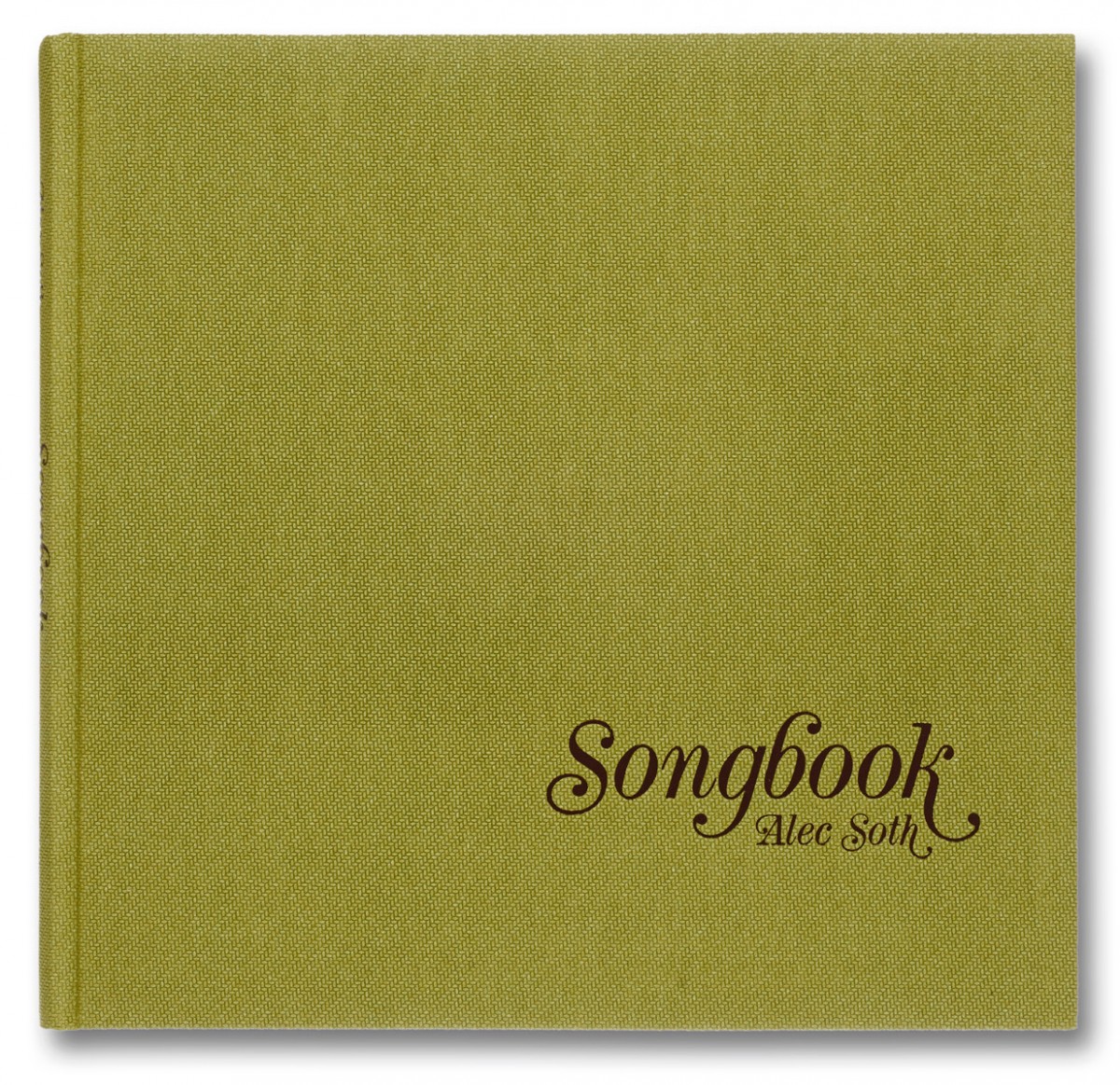

Alec Soth’s stirring Songbook – released only weeks ago by MACK, but already hailed critically as a classic – is an ideal example of a brand new publication that deliberately rejects such aids, and continues to borrow directly from American Photographs in its ‘virginal’ presentation, as well from the traditions of ‘lyric documentary’ photography that Evans initially established. ‘Unsullied except for a page numeral’, every image printed in Songbook was originally made in collaboration with a writer whilst on assignment – whether it be for Soth’s own self-published newspaper The LBM Dispatch, The New York Times, or otherwise. Yet when it came to making a photobook, Soth deliberately stripped the photographs of the written texts that originally accompanied them. ‘So much of the power of photography is this imaginary world that’s generated from a photograph,’ Soth explained recently, ‘I love what text can do for them, but I also love the opposite; its much more open-ended.’

Like American Photographs, rather than attempting to document or explore the United States in a literal or geographical sense, Soth’s book offers both a photographic and conceptual terrain – an image-nation – that only becomes fully, independently and uniquely established in the mind of each reader. ‘Pictures rub up against each other and let the imagination kind of ping off in different directions,’ Soth reflects, ‘They generate other ideas, other possibilities, other interpretations.’

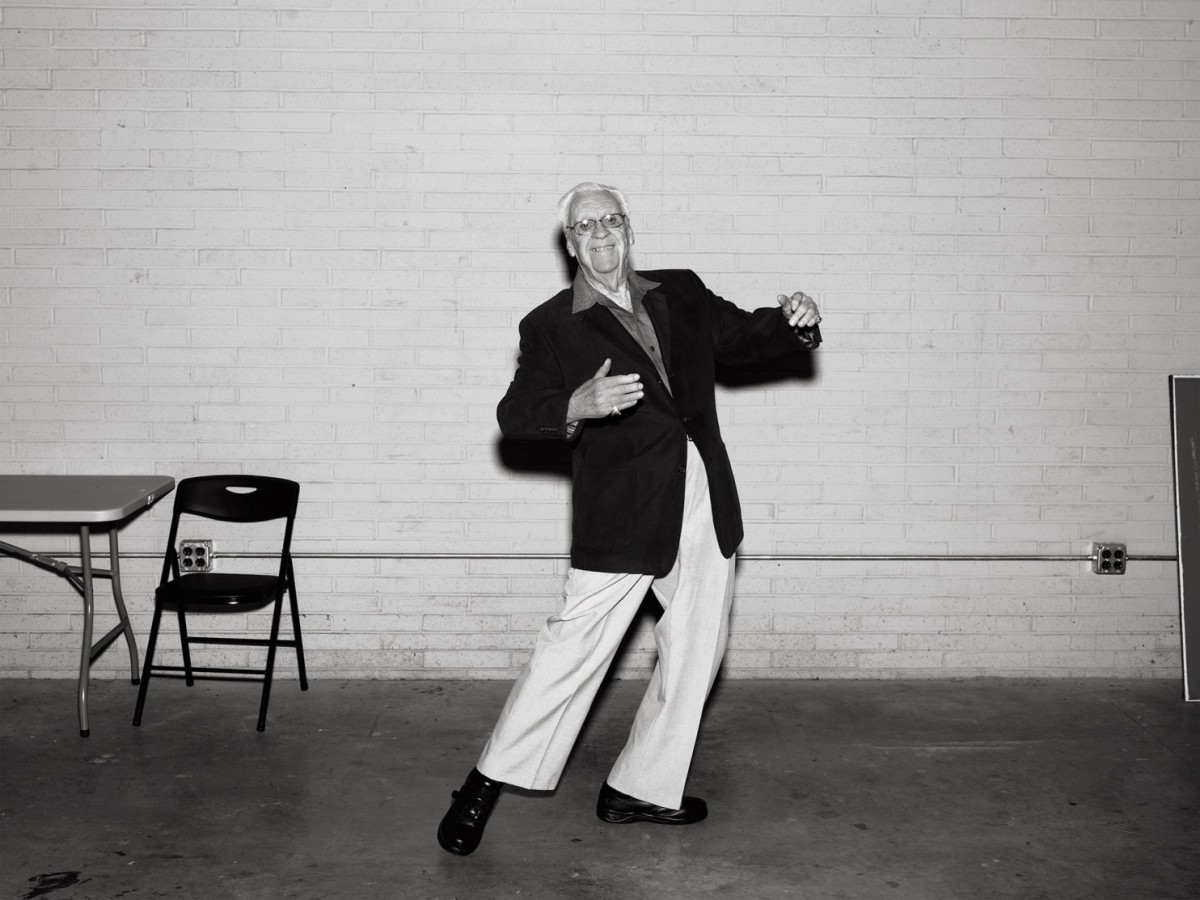

What we see in Songbook’s opening photograph – printed opposite the book’s title page – is an elderly gentleman smiling brightly at the camera, as he gracefully waltzes with an imaginary partner across a cement floor, past an empty chair, a table, and a white-brick wall, and through the centre of Soth’s frame; what we read in this image is another matter, and is primarily determined by how Songbook subsequently plays out. But as the opening of a photobook, this lone dancer seems to serve as the ultimate proxy for both the author and readers of such works; he offers us the perfect invitation – to see, to read, and to dance with the images that follow, and at the same time realize that, in doing so, we are simply dancing with ourselves.