“There’s a basic rule which runs through all kinds of music, kind of an unwritten rule. I don’t know what it is. But I’ve got it.” Ron Wood

When talking about the medium of photography, I often like to speak by analogy. Usually I prefer fishing or poetry analogies, but when discussing the charms of the singular photograph, I like to talk about pop music. Like a photograph, a pop song is a humble enterprise. Generally only a few minutes long, pop songs combine simple lyrics and melody in a repetitive verse/chorus structure. As with photography, the creation of a pop tune is easy enough for any amateur.

What, then, makes one pop song better than another? I’m certain that if one were able to poll the world’s greatest songwriters, there might be some consistent responses (simplicity, catchiness), but the overall definition would be a mystery. In the end, most people would simply say that they know a good song when they hear it.

But this also means they need to hear it. There are currently twenty-six million songs available for download on iTunes. It is hard to know how many of those songs are good. But as I write this, the #1 song in the US, France, Germany, Finland, Spain and Switzerland is Happy by Pharrell Williams. Is it a good song? Both my wife and children seem to think so. But is it good because it is popular or popular because it is good? This is an almost impossible question to answer. What is clear is that increased visibility has an impact on what is considered successful. “What makes a ‘good’ pop song?” asked Boy George, “Airplay!”

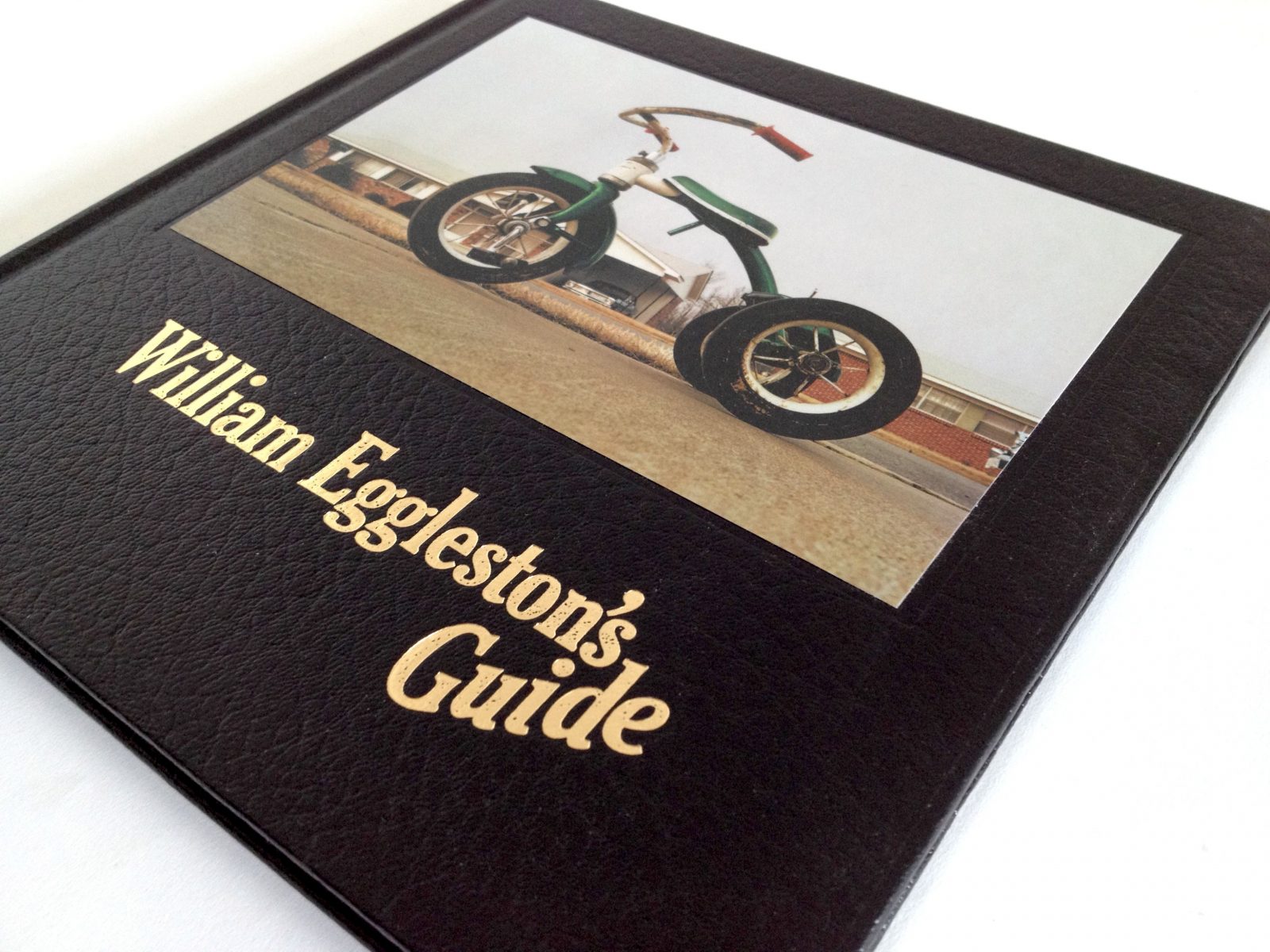

Photographs are little pop songs. But where there are 26 million songs on iTunes, there are 16 billion photographs on Instagram. How many of these are better than the iconic photograph of a tricycle on the cover of Eggleston’s Guide? To what extent does being on the cover of a book published by the Museum of Modern Art affect the attention and respect we give that photograph? As with songs on the pop charts, it is nearly impossible to untangle these questions. In the popular arts, a work’s popularity is inextricably linked to its success.

A couple of years ago I tried to analyze the success of Dorthea Lange’s Migrant Mother. I’ve always been fascinated that one of the most iconic photographs of all time is so technically flawed (the mother’s eyes are out of focus and an unwanted finger in the lower right corner of the image has been painted out). What makes this image so powerful? In order to understand this, I found five different migrant mothers and photographed them with their children. Are the photographs good? One of them might be okay. But of course it has nowhere near the power of Lange’s image. To set out with that aim is pure folly.

In the end, it only causes me frustration to analyze these questions about photographs. Whether it is ‘likes’ on Instagram or tens of thousands of dollars at auction, the gauging of success of a singular photograph seems fruitless, even dangerous. For this reason, I’m much more concerned with the book of pictures, the album, than I am with the singular photograph, the song. In the end, just about anyone can take a picture as good as Eggleston’s tricycle. But only a handful of people will ever make a book as good as Eggleston’s Guide.