In this conversation with David Batchelder, we hear about his new body of work, Tideland, and his approach to capturing these otherworldly landscapes.

Photoworks: The series Tideland is an immersive experience, creating curious worlds where we aren’t entirely sure of time or place. Can you tell us how photography helps in finding and creating these kinds of spaces?

David Batchelder: Most often we approach photographs with the understanding they are made from reality. When photographs reveal another reality – such as in Tideland, where we see there is another reality within the reality we know as the beach, they gain a sense of mystery that makes them much more interesting for me. Made from what we know to reveal that which we did not know. The Brazilian photographer Sofia Borges has found the language for this tension with reality when she writes “…the photograph’s ability to forbid meaning”.

PW: Is it important that people are unable to identify the locations?

DB: Yes, absolutely. I found it impossible to get away from the ‘real’ tideland if there was anything in the photograph that one would identify as beach or let the mind orient. Never a horizon, nor a blade of sea grass, or shell and never, ever a person (to adapt a quote from Walker Evans about the folly of photographing the beach) …nothing that keeps us on the beach our mind already knows. A couple of photographs in the book do show recognizable beach things, but these are not really what they appear to be. At times when the image is so clearly not of the beach, I might, for the shear whimsy of it, put in a small, telltale piece of the beach to exploit that tension between the beach we expect and the tideland of the book.

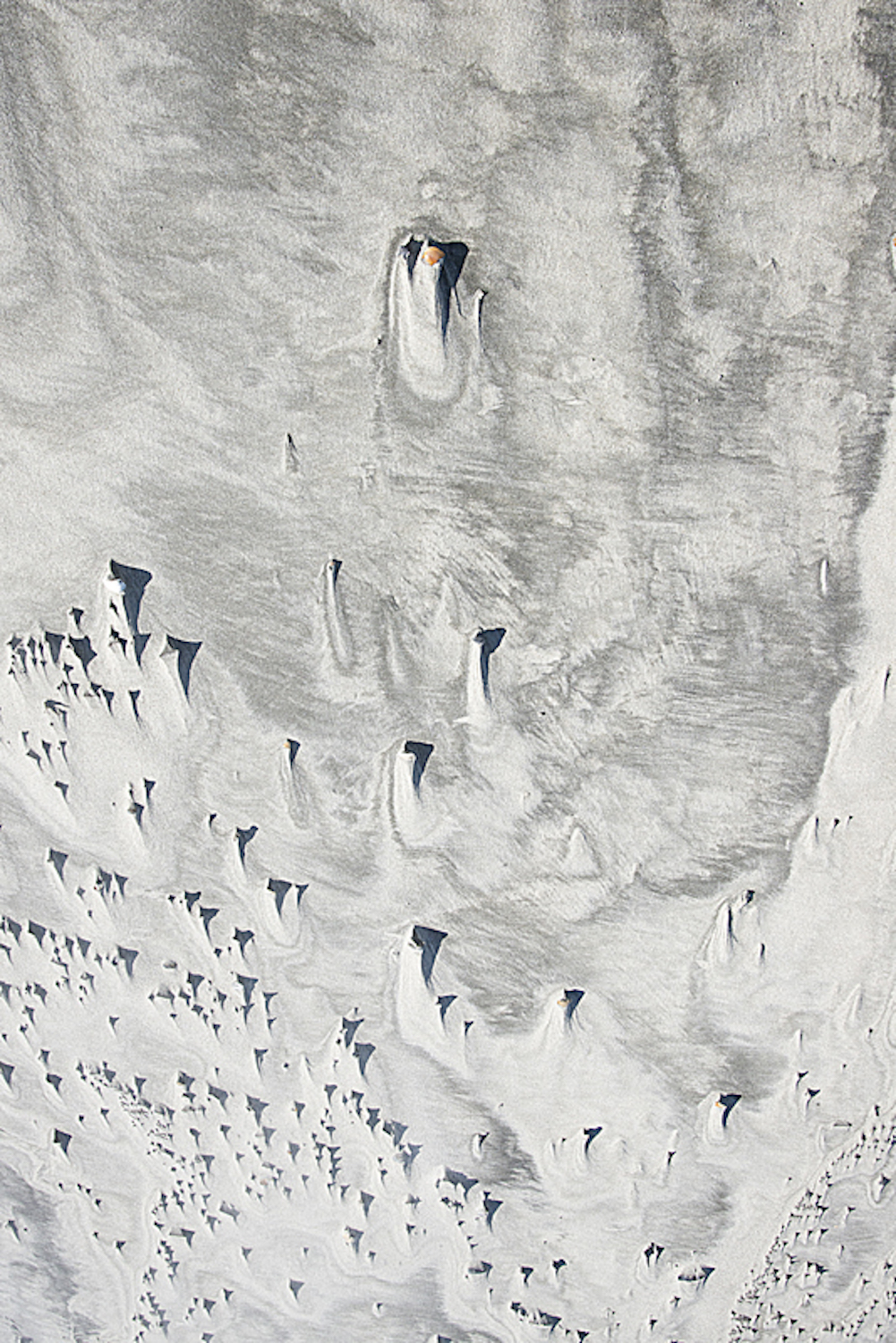

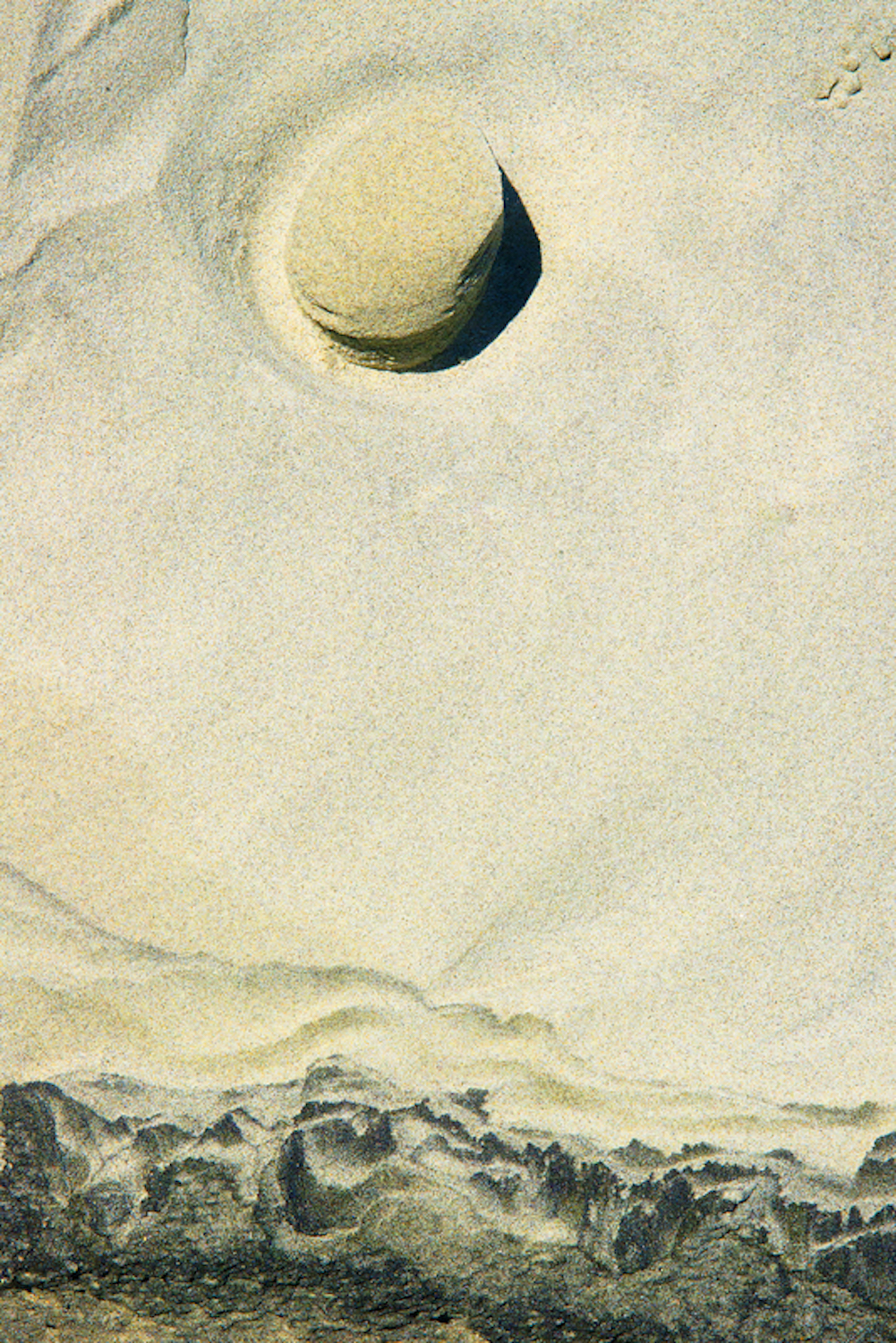

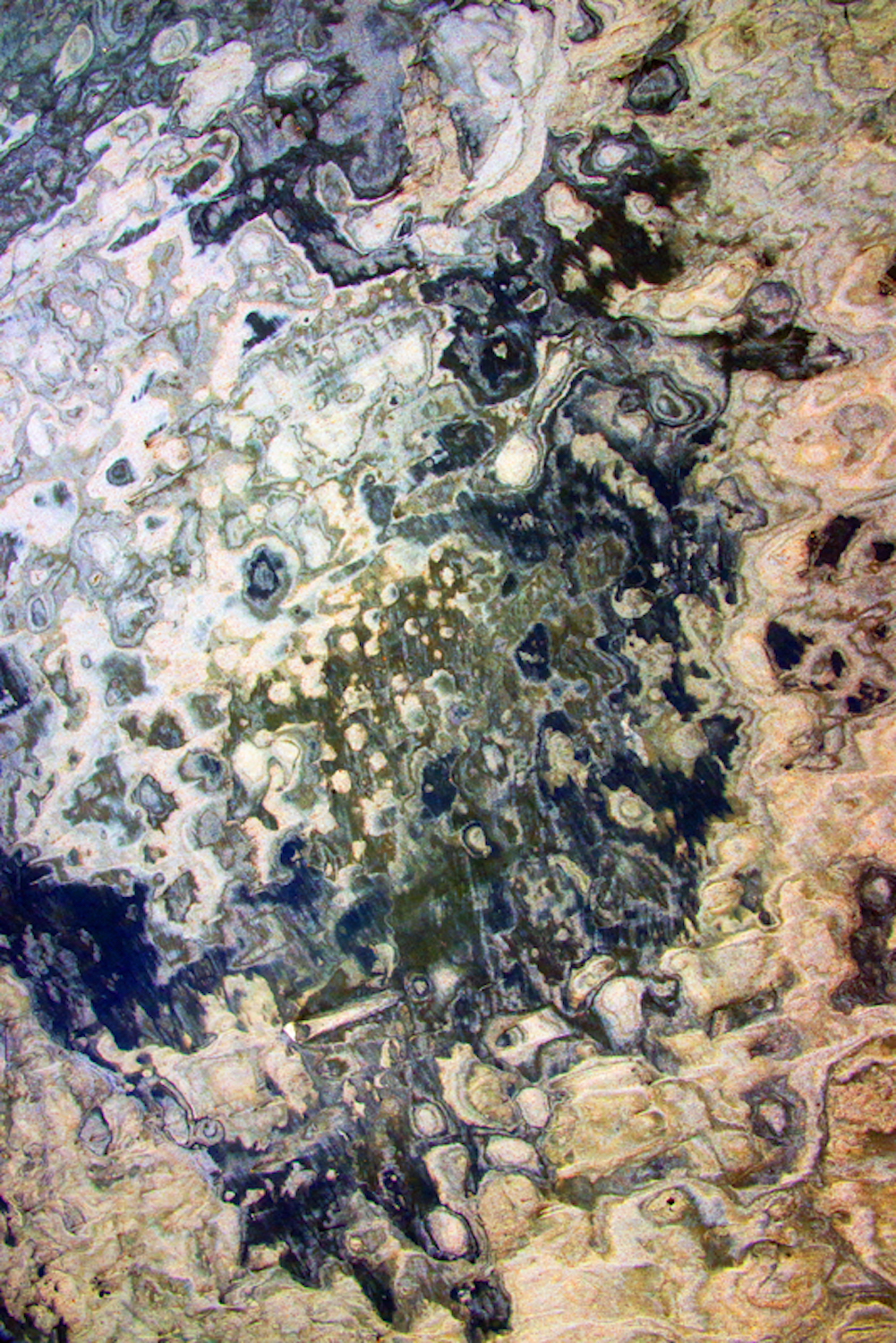

Untitled, from the series Tideland © David Batchelder

PW: What do you hope viewers will take away from your work?

DB: I do not wish to be rude, but I can not think a bit about anything as rational as what the viewer gets when I am in the tideland on the beach. One of the advantages of having been completely away from serious photography these last thirty years is I am as free from influences and needs, those subtle and not so subtle forces that shape our understandings about what a photograph is and should do, as I can possibly be. I am not concerned about trends that may be popular, what is currently the accepted thought about photography. I am as free as possible from all those forces and most content to be self indulgent.

When Anne Wilkes Tucker was looking at the tideland photographs, she stopped at one for some while. I started to say something about that image, but she stopped me abruptly, saying: “Don’t say anything…allow me to enjoy that which I am discovering“.

David Campany, who just loves to speak to actual images and is so perceptive, does not do that in his essay in Tideland. If two of the wisest voices in photography know the wisdom in getting out of the way of the viewer, I would be wise to do the same…you think?

I will get out of the way and wish the viewer enjoys their travels through the tideland.

Untitled, from the series Tideland © David Batchelder

PW: Is there a particular time of year? Of day?

DB: As hard as it may be to believe, the tideland is on a resort beach in the south… The high season on the beach is in the summer when the crowds come seeking relief from the heat and humidity inland. I go north, also to escape. I am on the beach with my camera mostly when the tide is out, exposing the sand and muck that has been shaped by the tidal waters. The highest tides and the storms that most rearrange the sand come in the fall. The light is of little concern, although I avoid shadows because they tend to bring my mind back from the tideland to the everyday beach.The light I do embrace in a photograph is the light that appears to emanate from within the picture. There a few of these instances in the book.

PW: …or frame of mind that you need before work can proceed?

DB: Nuts!! I am as completely detached from reality as possible. I was drawn to the beach and back to the camera in a serious way by a compelling feeling that there was something ‘other’ there, reaching out to me. Bored making the best pictures ever made of the best grandchildren in the world, I began wandering around the beach, looking down at the sand. Broken shells in the sand appeared as faces, shouting out to me. A rational person would seek to dispel such a notion, but I was drawn in by this. Over time and with much work disengaging from the beach of our every day understandings, I was able to, more readily, be in the tidelands. Whenever it felt mysterious, enigmatic, inexplicable, weird, divergent, unexpected or simply odd, I embraced it… I found I thrived on the irrationality of it. In a clinical sense. I would most probably be diagnosed with a dire case of ‘pareidolia’ as I am finding meaningful form in the chaos of the sand. Being able to connect with an indelible marker in the brain that comes from our primal beginnings-with a camera. How good is that?!

PW: What is the process of you venturing down to these tidelands.

DB: I travel the same section of resort beach – about a mile and a half – each time, over, and over and over, and have done so for five years now. Only infirmity will stop me in these travels. Some more rational minded than me might see it as obsessive behavior… maybe so. But I am driven by the wondrous new things I see. Nothing preconceived, yet always something new encountered in the tideland. It takes about three hours to travel that space. Usually I make about a hundred exposures, often many angles/views of the same encounter in an attempt to lift the forms from the beach reality to the tideland. Back home I process the digital files, making proof prints that I hang up and live with until my next trip out. By this process, over the years, my ability to see in the tideland, has evolved and grown far beyond anything I could have dreamed of when I was first drawn to the beach.

Untitled, from the series Tideland © David Batchelder

PW: Taking photos of the beach in the way you do requires you to constantly adapt your viewpoint.

DB: Perhaps the most frustrating adaptation is I have no control what I might encounter or when. I might encounter something new and exciting, something I would like to pursue over some time, yet it is gone the next day and I might not see it again for some time or ever again. I am always at the mercy of the tides and wind as they move the sand and muck. When I encounter something interesting in the sand, I work with it from all angles to release it as much as possible from the beach reality… to put it into the tideland landscape of my mind.

PW: Did you find that breaking out of the normal way of seeing helped you in creating these ambiguous landscapes?

DB: Yes, that move away from the ‘normal’ was crucial, yet not so new for me as I have always felt the best in art, and especially in creative photography, was contrarian; challenging the conventional, the ‘trends’, seeing differently with the camera. For better or worse contrarian is my personality. Jerry Ulesmann once said, “David is worth his weight in aspirin!“. Very clever, yet nasty, I thought. But he was right and, over time, I have learned it accept my rebellious angst and use it. I feel blessed to have no urge to make photographs that look like those made by others or have already been made.

PW: Was this contrary attitude prevalent in your work back in the 1970’s when you exhibited with Uelsmann, Judy Dater, Linda Connor, Leslie Krims, Emmet Gowin; those thought to be on the cutting edge of American Photography? ( see: Private Realities: Recent American Photography-Museum of Fine Arts-Boston and the New York Graphic Society)

DB: I had not given much thought about my early attitudes and photographs as I was drawn back to the camera on the beach until a student from back then emailed me to tell me she had seen my name about Tideland and had googled David Batchelder, wondering if this David Batchelder of the book was the same one that had started her in photography in college so many years ago. She wrote that as soon as she saw the first ‘beach’ photograph, she knew it was me. She got me thinking back. I could see that in much of my early work I was searching for new spaces and vistas not willing to accept the quotidian way of seeing things.

Skull © David Batchelder

Untitled © David Batchelder

PW: When you found yourself drawn back to making serious photographs after being away from photography for so many years, photography had morphed from film to digital. Being drawn into the beach as you were, how did you deal with that change?

DB: Very quickly I found a tutor who could tell me what I needed to know as I progressed. What transpired on the beach that brought me to tideland would not have been possible for me with film. I would not have had the physical strength and stamina to make and process all the thousands of exposures and negatives. And that old cumbersome and time consuming process would have precluded the growth in my vision. You see, after hundreds of prints made on the beach I was still locked in a vision of the quotidian beach that I could not escape from. At that time I was seeking something other that I sensed was there to see. Slowly, over time I began to see the tideland of the book. It took many thousand exposures to leave the every day beach– to arrive in the tideland. The ease of digital made it possible to discover and grow a new vision- to see Tideland.

Excerpt from David Campany’s essay, the full essay of which can be read in the book Tideland, published by Schilt Publishing.

“I am inclined to think of David Batchelder making his work because he wants to, has to, and nobody else will. Imagine him on that island, walking from his home on Seagrass Lane to the sands that sustain him.

So here we have a book, a large book, of Batchelder’s sustenance. You will make of it what you will. Indeed, I suspect that with such imagery ‘making something of it’ is unavoidable. Nature’s abstractness, typified by beaches and rocks, tends to provoke us to great extremes of reaction: the universal or the particular; the sacred or the profane; the precious or the pointless; the significant or the meaningless; the lofty or the low. It has something to do with the involuntary rush, the intuitive projection we make upon both nature and what seems abstract. It seduces our unconscious wishes into revealing themselves. Is it possible to look at these photographs without seeing something in them?”