British Litter Bins 1950-66

Text by Ian Leith

Published in Issue 15 of the Photoworks Annual in 2010/11, we revisit British Litter Bins from Ian Leith, presented originally by Martin Parr to coincide with Brighton Photo Biennial 2010.

The TV archaeologists who call themselves the ‘Time Team’ seek evidence of the past in the form of artefacts, structures and all forms of cultural clues but, since 1839, they and other archaeologists have largely ignored one essential archaeological media: photography.

Whole hoards remain to be excavated and will one day equal the rewards of Schliemann at Troy. If even a fraction of the amount of science and interpretation applied to ancient coins went into photographs inside the archive, then various chunks of history would require revising or rewriting. Despite increasing access to topographical collections, no attempt has ever been made to create an overview of the earliest known urban photographs of Britain.

In 21st century Britain, it is as if Harrison Ford was unable to detect the gold in front of him; despite millions of photographs online and inside archives, an archaeology of photography remains a celluloid or digital fantasy. The unexcavated valleys of photographic tombs are ubiquitous within Suburban England, but still, await the right ‘eye-trowel’. Given how much has been lost since 1839, we might despair at the extraordinary dearth of exploration; the almost inexplicable absence of attention.

Martin Parr, who has selected these images, certainly has a track record in wielding the eye-trowel, both behind the lens and in the collecting of images. But such scrutiny is so rarely applied by historians inside the archive. ‘The archive’ is a term commonly found in much contemporary discussion, but this is usually restricted to purely theoretical constructs; many of which are arcane and apparently impenetrable. But crucial clues can be found which can aid our navigation through a series of treasure islands. Archives are like superstores, hypermarkets, outlet villages or warehouses; full of visual history. But, despite a mantra of access, photography often remains in the (metaphorical or actual) basement.

It is ill-selected, insufficiently interpreted and digitisation is often subject to unknown criteria, so the medium remains what Derrida calls an ‘ecart’ – a gap or absence.

Scrutiny of selected themes within the archive can add layers of contemporary interpretation to fill in some of these absences. These images of litter bins come from several hundreds relating to the topic, from over 100,000 photographs held by the Design Council Archive (DCA) at the University of Brighton. Litter bins represent a small fraction of the wide range of objects represented: signage, street furniture, house-ware, furnishing, décor, all appear in the archives of this state-endorsed body, which started as the Council of Industrial Design (1944-1971) and later became the Design Council (1972-present). The sources of the photographs are not just official (many come from photographers employed by CoID) but also derive from manufacturers, designers, architects, agencies and professional photographers who contributed to the Design Index. The level of documentation can vary, from a single print that exhibits all these sources at once, to a print with no information at all. At times we know everything – the photographer, manufacturer, date, location – at others, the location is unknown but can be deduced (this is often London; a point evident from the backgrounds). In a few cases, the style of bin became popular and examples would have been found all over Britain. Most of the actual bins are now historic artefacts since few have survived.

The bins represent a conscious, perhaps over-conscious, effort to bring design into public spaces. Apart from the DCA and the V&A, few other archives hold any equivalent material, depicting what we might describe as ‘official ephemera’. The two decades after the Second World War were hampered by an inability to reconstruct urban areas. Architects and designers were keen to apply their skills to specialised markets with a steady demand; a demand that often went beyond their normal architectural remit. The objects they designed could be seen as representative of a taste influenced, not just by cheapness and durability, but also by the ideals of post-war Britain. Design here meant a unique opportunity to apply a socialist utopian vision held by planners, engineers and architects educated in the Garden City movements and the total planning which took place even during World War Two. The deconstruction of the urban fabric created spaces and ways of approaching the public realm which had not existed prior to 1939. It represented a chance to apply ideal modern practices which were inhibited in architecture due to cost and shortage of materials. These strict control on building materials were imposed until almost 1960, so much design was funnelled into prefabs, conversions, interior design and public space.

The original purpose for these illustrations has been subverted by a series of re-evaluations, which depend on the responses of wholly different viewers, applying a host of quite different perceptions, from those which were assumed in the 1950s and 1960s. All these DCA images would only have been seen by local councils and those linked with their design or manufacture; they would never have been on display or reproduced for the sort of public which now looks at a selection by Martin Parr. Thus our reading of these pictures must be informed by the previous – and quite limited- intentions. As Catherine Moriarty notes, the Council prioritised the appearance of a product, rather than its efficiency as an object of actual use. We now look, and even marvel, at some of the unexecuted designs in a different, broader way: immediately spotting echoes of other contemporary styles, or wondering at the vulnerability of some of these designs, which would not have survived even modest usage in a public park (examples of battered bins also exist in the DCA with notes on how some materials like reflective steel were unsuitable for locations close to parking vehicles).

One of the crucial curatorial questions raised by the photographs must be, what level of inscription should viewers be given? The reverse of at least one of these prints is almost totally covered by text in the form of sources and captions, so what, exactly, of fairly, should be included here? Who should do the editing? And by applying what criteria? How much interpretation should be given? In an era of digital reproduction, almost none of this context is included alongside the image, so digital pictures are especially vulnerable to the loss of non-visual meaning. The University of Brighton holds catalogues of suppliers, providing further context, that can be added to the visual metadata. We could read these photographs as a series of blank receptacles, subject to our imaginations; or we can feed in extra layers of meaning.

Specialist archivists are well aware of these dangers or responsibilities and strict standards exist. Yet, for photographs, we are always tempted to escape such bonds of meaning or intention. Only a limited number of archivists or curators can dedicate themselves to the innumerable singularities of photography, which quite often confound all the cataloguing and tagging systems applied to conventional objects and texts. The unwritten archival law is that older media receive attention first so, despite selective digitisation and a constant public demand, photography remains the Cinderella who has not yet made it to the archive ball. Much of this effort can now be re-imagined or re-engineered via the web. Like genealogy, it is now possible to contemplate the use of volunteers as the excavators able to conduct the necessary transformation of the medium. Without efforts like this, photography will continue to be excavated by chance intervention. Although photography is often ignored by archaeologists, who suffer from a form of archival and visual snow-blindness, if we can begin to create these interventions within the archive, it might still be digitally harvested.

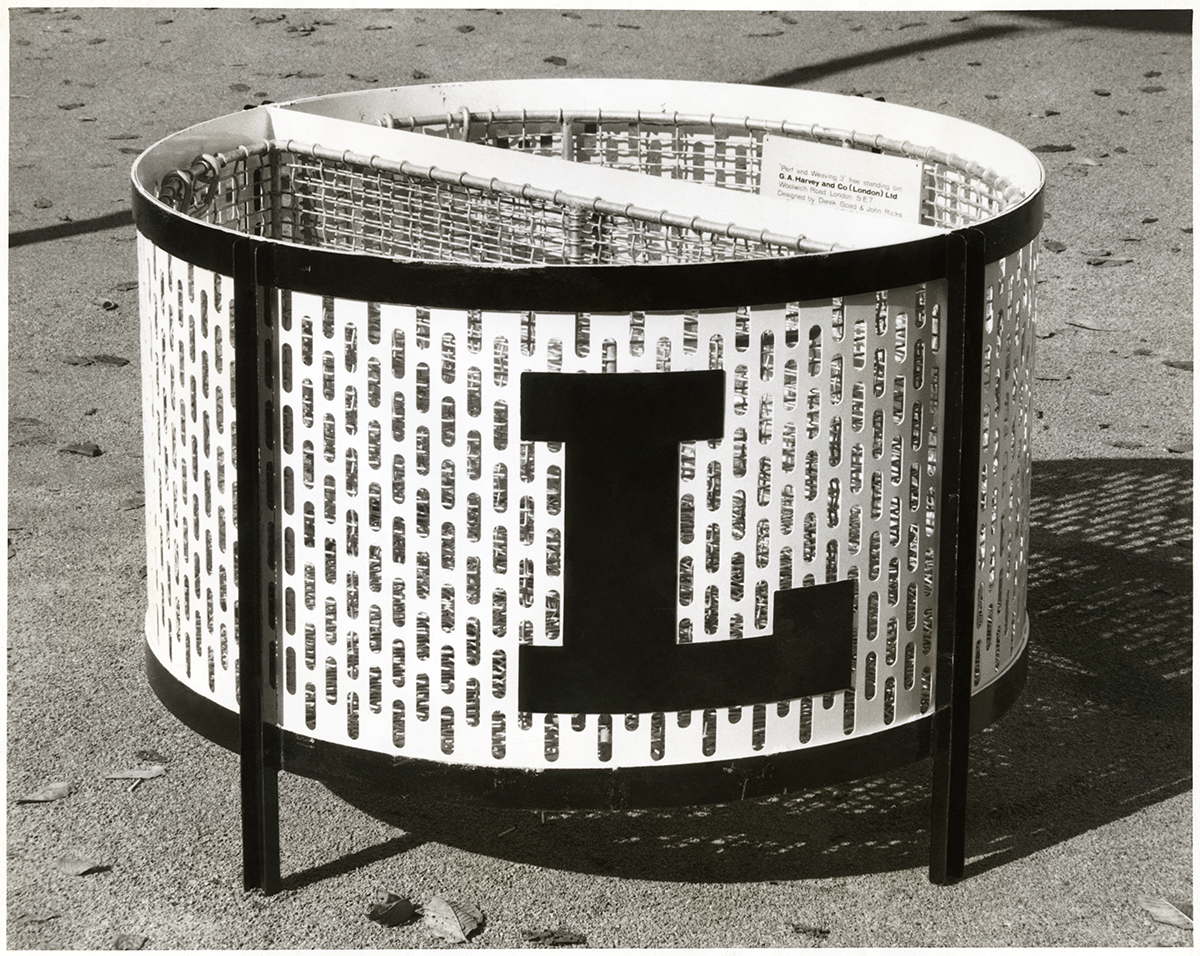

Martin Parr has selected twenty-four prints of litter bins, fourteen of which are presented here. Most are in standard 8×6 inch format, and all are black and white prints taken between 1950 and 1966. Many of them are accompanied by captions on the reverse. DCAH458/12 is the only one which comes from a creator still known today. David Mellor (1930-2009) is an important designer and writer, far better known for his cutlery designs. His bin designs were connected with Abacus Municipal Ltd., the British Railways Board and National Benzole Co. Ltd. Bin DCA601947, incorporating the large letter ‘L’, comes from designers working for the architect Donald Forrest. It and others display distinctive 1950s typefaces. The bin in DCA509038 was produced for a council still maintaining the tradition of civic heraldry. Although they were often removed from the public gaze, such heraldries sometimes re-appeared decades later: all the street furniture in Regent Street in Westminster received a ‘heritage’ makeover in the 1990s. Photographers are identified in DCA509038, DCA6869 and DCA5922554. Other photographs were taken by the manufacturers, which in at least one case, still survive (see www.furnitubes.com). Although manipulation of the images was frowned upon, at least one picture (DCA1960/16) has clearly received this attention, in order to enhance the outline of the bin. Colour images are known to exist in the Brighton archive, but were mostly created after 1965 and so are absent from this selection.

Several examples were situated and photographed at the CoID open-air display of litter bins in the Victoria Embankment Gardens: a set of thirty-four litter bins which had gained a diploma or commendation in a competition and put on display in October 1960. John and Sylvia Read, the designers of DCA602511, are mostly known today for their collectable furniture of the 1950s but, because they are represented in the Digital Design Slide Collection, a few colour images of litter bins are known. DCA592544 was photographed in 1958 by Verity Press Features of Wardour Street. Like many post-war photographic concerns, this company is now almost entirely unknown. Without the online addition of rare registers of professional associations, no tools will exist to provide provenance. The recent past is the most unknown and most unfashionable, but there is still time to build in access. If we do not, the last decades of analogue photography will be harder to interpret than the first: we already know a vast amount about every photographer of the 1840s and 1850s, but what records will exist for the 1950s and 1960s?

The creation of a historical synthesis is possible for design history, or for urban and topographical photography, but there seems to be little demand for such overviews, or for essays relating to specific archival holdings. Why do English archaeologists, architectural historians, and urban gurus avoid the archive? This is partly due to an inherited ignorance, which finds engraving and fine art to be superior to cheaper forms of illustration; partly it is down to the daunting prospect of tackling large archives; and partly it is because many smaller archives are unable to excavate their own basements (there are honourable exceptions to this, but, like many forms of photography, the absence of any commercial market for the past determines what we know today: nobody has bothered to create an audit of non-portrait daguerreotypes of the 1840s, for example). Beyond what archaeologists create themselves – which are mostly duplications of existing records – many do not believe that any photographic archive exists at all, or that any previous images have individual histories which can aid interpretations of the very environments they are ‘recording’. Above all, there is an underlying and unfortunate unwillingness to acknowledge that photography has more than a vestigial link with archaeology.

Such use of photographic illustration is still driven by aesthetics, serendipity, and a Francis Frith nostalgia. The bulk of official and commercially driven images remain largely untapped and questioned, even though such concerns are known to incorporate the work of reputable photographers. We continue to be seduced by photographs but, after more than 170 years, we remain incapable of adequately questioning them.

Ian Leith is a photographic archivist and a historian of sculpture. He is one of the founders of the first online dictionary of London photographers 1839-1900.

Read more Photography+ Become a member and receive latest issues of Photoworks Annual