Spare Rib co-founder Marsha Rowe shares her thoughts on the formation and evolution of the magazine and the use of photography in raising the awareness of women's roles in society.

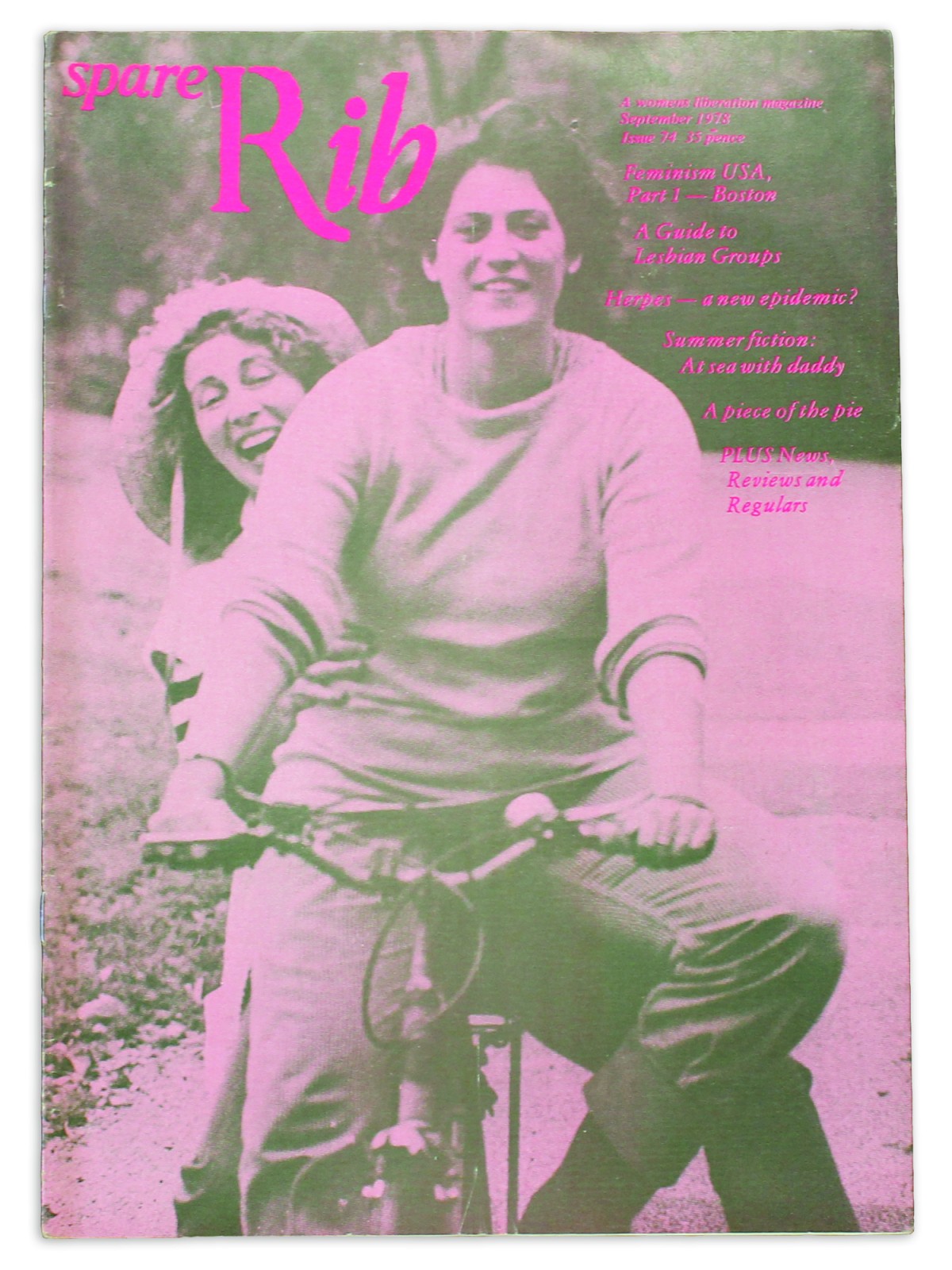

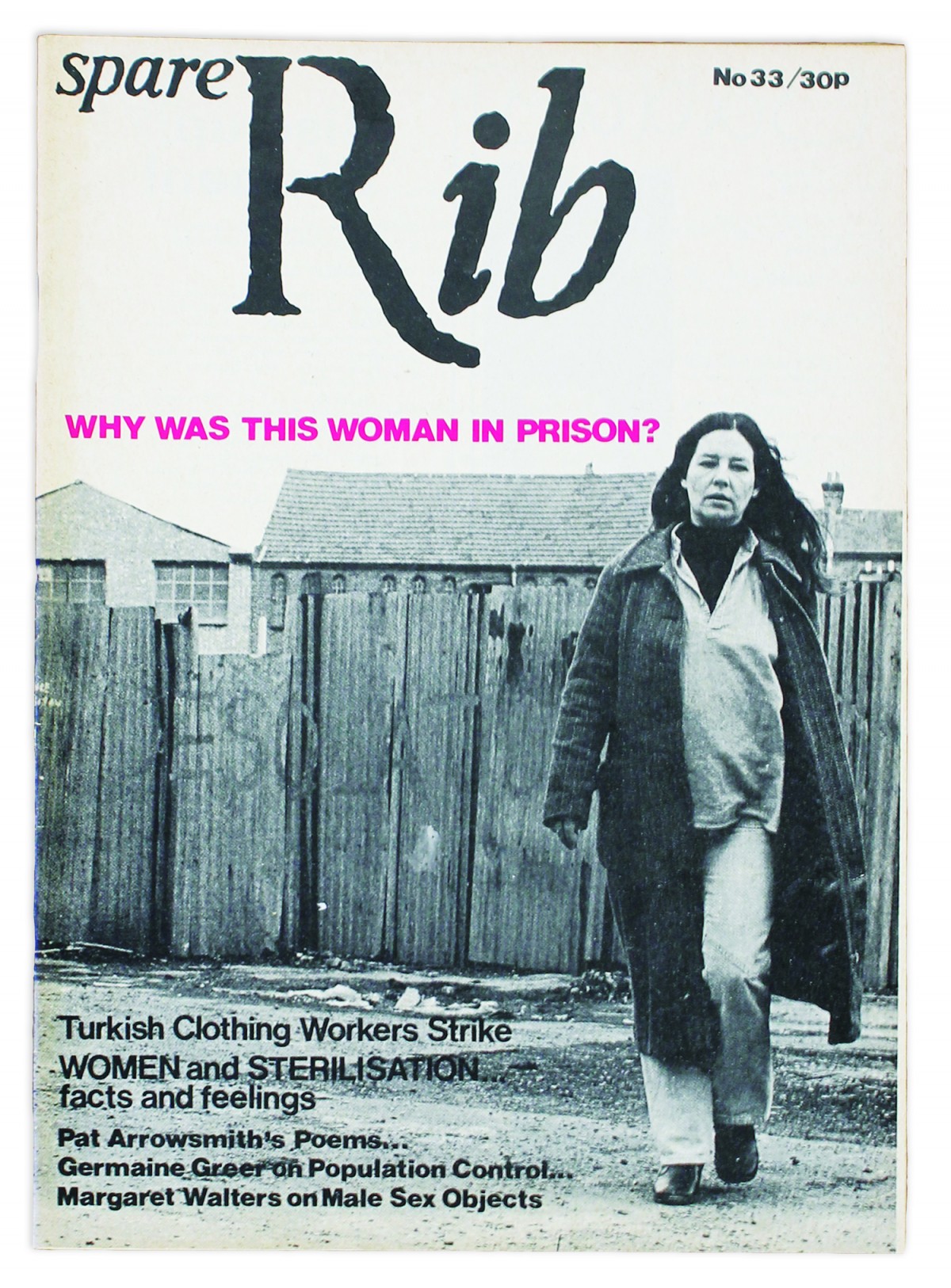

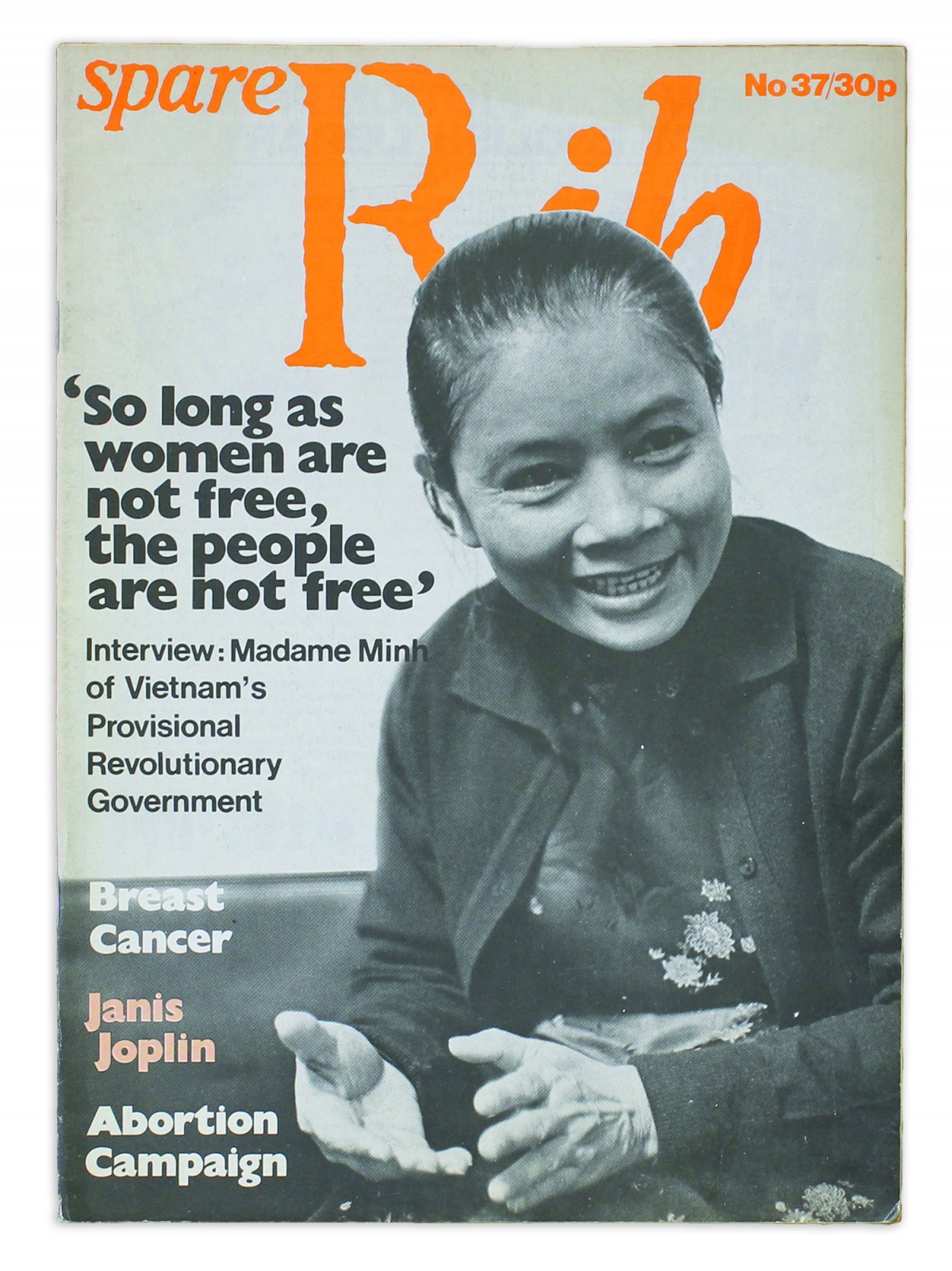

The power of front-cover magazine photographs is to whisper intimately and resonate loudly in the mind, persuading, or not persuading, someone to buy the publication.

In the case of Spare Rib magazine, we were competing on the newsstand alongside existing women’s magazines of the time. It was 1972, and the women’s liberation movement was in its infancy. Hostility to the new feminism was expressed everywhere, in all of the media, although women’s magazines were beginning to publish the occasional article addressing questions of women’s independence. That did not mean that any of those magazines had shifted their attitudes. Women were on the planet as adjuncts to men, and if there was not a man in a woman’s life, the magazines wanted to help her find one. Spare Rib was pioneering the view that women’s lives were about much more than that. A lot had to change.

The first issue carried a photo of two young women smiling naturally, without heavy make-up, looking like anyone’s best friend in a relaxed mood. The photo was taken by Angela Phillips, who had been working as a photographer for just a short while. Soon she turned to journalism as a way of making her living, but this photo stood out on the newsstands because it was so obviously not a shot of models, nor was it a shot that posed the women seductively or invitingly or remotely, as an icon of femininity. This expressed the new ethos, the principle of feminism that motivated the publication of Spare Rib. The search for a changing role for women in a society that needed changing, to establish a level playing field for women, and the space for women to rediscover their voices and express themselves in new ways. This involved both anger and joy. And to find photographic images that would both communicate to a potential buyer of the magazine and convey these new hopes—or the difficult realities—meant a proliferation of different approaches.

To take one example—the front cover of issue 3—the photo was of a middle-aged woman looking away from the camera, her face partially obscured by overhanging rocks that made up the background. It was a composite photo to illustrate the main feature in the magazine describing the experience of agoraphobia—the fear of open spaces—that kept this woman trapped indoors. But it was illustrative, if you like, of a wider issue—a woman confined by her responsibilities as a housewife. It was an image that resonated beyond the subject of the article.

This was the approach that became useful in commissioning and choosing the cover photo. Whether it was an article about the history of dolls, or about the liberation of cutting off long locks, or about a screaming fan at a rock concert, or the need for more nurseries—with a cover photo of a woman travelling on a bus holding her baby in a sling and another child in tow—those cover photos were in stark contrast to the conventional covers on all of the other contemporary women’s magazines, from the glossy and expensive to the cheap and cheerful.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

In fact, the Spare Rib cover photos were helping to attract women to the magazine. They spoke to their own experiences. They were images with a story. There were often groups of women in a photo, rather than a single face shot. Or a photo of a woman’s body in action, or disguised under a mask of painted lines. After a decade or so, increasingly the magazine turned to graphic covers, replacing the cover photo with ideas- or action-oriented images.

By then the women’s movement had been a very effective force for change. There had been a raft of new legislation: against discrimination on the basis of gender, and for equal pay for equal work, for maternity leave and pension rights. Women had been entering previously male- dominated professions. Girls’ expectations at school were changing. Romance lived on, but girls no longer expected to be provided for, and their dreams went beyond motherhood.

The 1980s were a period of a backlash. The Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, had no truck with feminism, and, as a woman herself, in the top government job, gave the appearance that any woman could achieve whatever she wanted. In fact, by the end of the 1970s, the very concept of woman had come up for question. Change had proved to be far more complicated than anyone had imagined. Other, personal, aspects were being examined. The question of identity had become crucial. This extended to class, to race, to national ties, to religion and to the underlying psychologies of gender itself.

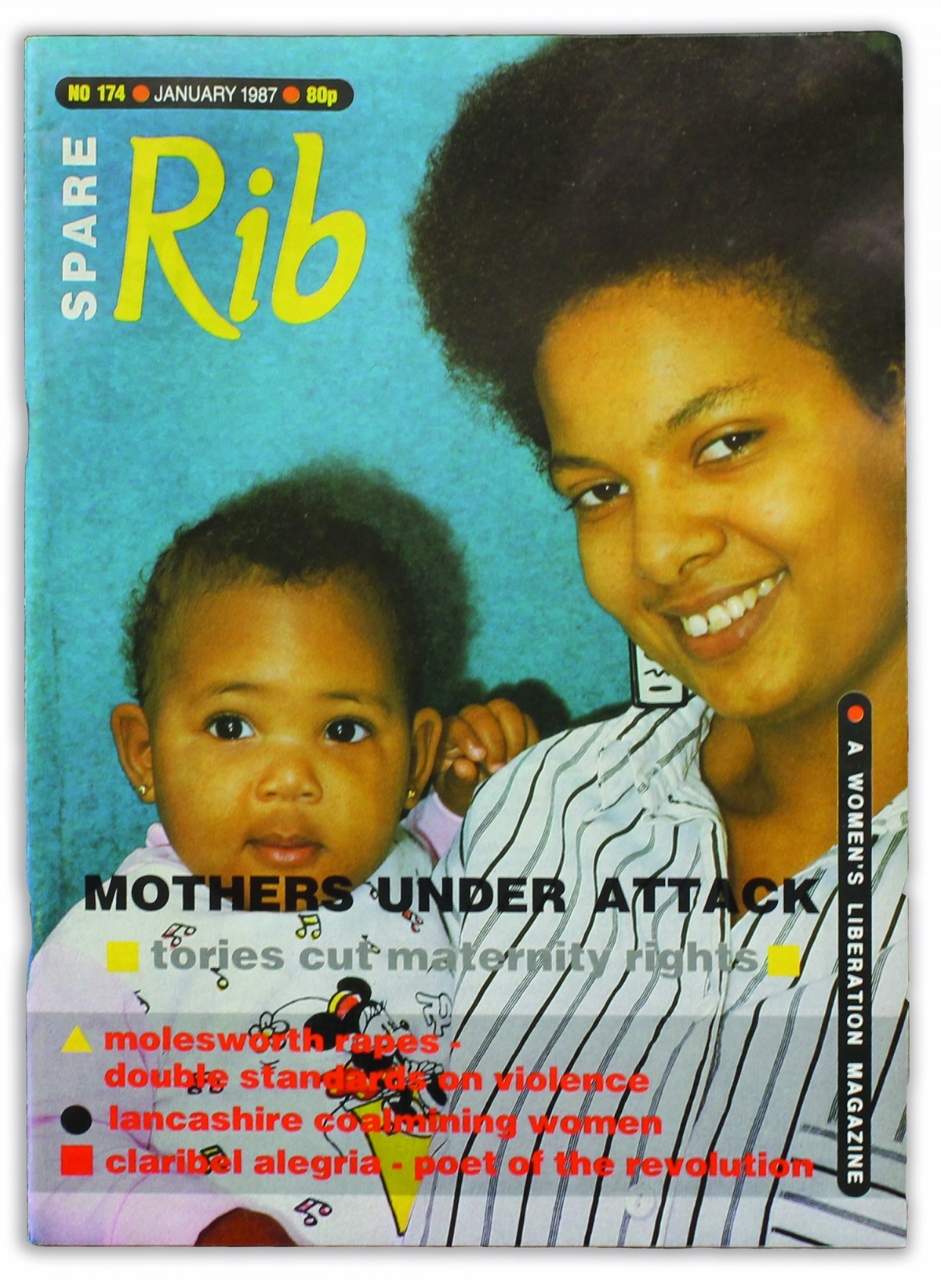

It is interesting that, as these questions were debated at a fierce, intricate level within the pages of the magazine, the covers of Spare Rib turned in another direction. Although there were occasional graphic images, more often there was a photo of a smiling woman, and frequently the subject was a woman of colour. Black and Asian Britons of varying ages beamed from the front pages of Spare Rib. It was as if a traditional format had been taken over to the better, to express identity politics, the pride of black feminism, the pride of achievement.

What was still important and significant was that these photos had a naturalistic look. This was in contradistinction to the increasingly air-brushed, highly manicured appearance of the front-page female face and body that was becoming the new print publication norm. As techniques for altering the photographic image had increased in sophistication, so the doctored image of femaleness represented in magazines became increasingly remote from how women actually are, in their bodies, and their selves. Ever-thinner models were used. Ever-younger. Ever-sexualized. It was if the 1980s backlash against feminisation was being played out a second time during the 1990s in the arena of magazines.

Today, while the political and economic landscape of the country is manifestly different, what is remarkable is that the debates of the 1970s are back in full force. Women are still doing most of the care in society. There are still fewer women than men in parliament. Women’s power in society has shifted, but not nearly enough. Inequality is still a battle fought by women at many levels, sometimes subtly, sometimes with enormous effort and difficulty.

Women across the world are in closer communication than before, and in this globally interconnected world the unevenness of women’s rights and freedoms is more visible. Photographs are as powerful as ever, in giving a snapshot of what women face, who women are, and of what they want and need. They can show the individual woman, unique as herself, against the backdrop of the discrimination that is shared by all women. Against the hope that equal rights can be achieved easily, photographs may demonstrate that the very concept of equal rights may be limited when it is framed by the experience of men. What women want from society, how society fulfils their needs, these are the ongoing questions.

Back in 1972 when I co-founded Spare Rib, women could not obtain a mortgage or hire a television without a man’s signature. While such legislative changes have been small steps towards equality, it is interesting to see that today the photographic image of woman is an ever-more sharply contested arena. Due to the recent efforts of a new feminist generation, the image of a woman can now be printed on a British bank note while the Page Three bare-breasted pin-up female image gathers increasing disapprobation.

Women’s magazines today carry a broader range of articles, but the visual ideal of femininity as it appears between their covers, and on photographic and catwalk models, is balanced on a fine line, often teetering towards too thin, almost spectral. Perhaps it’s on its way to falling off. Perhaps the balance is righting itself, as more women take their own photos, and assert power over the use of their image in ways that were unimaginable four decades ago.

<notes>

Spare Rib was published monthly from 1972 until 1993. It is now possible to see all of the magazines, plus additional articles on photography in the magazine, on the newly launched British Library website: www.bl.uk/spare-rib.

[/ms-protect-content]

Published in Photoworks Annual Issue 22, 2016

Commissioned by Photoworks