Anna McNay profiles two bodies of work by photographer Daniel Regan, Insula and Fragmentary, in her examination of mental health and photography.

Living with mental health issues is not easy. First, there is the struggle with the issues themselves, then there is the stigma attached. Society, in its general ignorance, has a fear of certain diagnoses – certain labels – and, as a result, many of us hide our struggles in shame. Feeling alone, feeling isolated, feeling like no one else could ever possibly feel – or do – as you do, let alone understand, is shaming – and shame is nothing if not self-perpetuating.

Recently, with the opening of the newly renovated Bethlem Gallery, I saw some work which shook me – shook me in a positive way – because, in it, I recognised my own behaviours, my own coping (or non-coping) mechanisms, my own shame. The relief of such cataclysmic moments, when, through looking at art, I am reminded that, actually, I am not alone, is always immense. Since this day, a few weeks back, I have been looking around for more artists whose work touches upon mental health and I was happily reminded of photographer Daniel Regan, whom I first met just over a year ago. Looking at Daniel’s work – as I have been doing in earnest this past week – has opened more doors to self-recognition, to feeling less alone, to a sense of hope and to a pride – a pride in Daniel for being ‘one of us’ who is willing to speak out, to reach out, and who, by empowering himself, empowers other people.

In particular, within Daniel’s work, I have been struck by the two projects Insula and Fragmentary. The former is a project that Daniel began in 2003 and spanned a decade. He describes the images – of beds, lamps, a smothered self – as ‘diaristic’ and ‘therapeutic’. They document a period of ‘emotional difficulties of living with a chronic mental health disorder’, using photography as ‘a tool for recovery’.

Daniel began taking photographs at the age of 12, when his grandfather (a keen amateur photographer) gave him an old Pentax 35mm camera. ‘It started as a natural way for me to manage when I was experiencing mental difficulties at a young age,’ he explains. ‘For me, the camera became a way of expressing those feelings – which I often didn’t understand – without having to be concise in the same way one needs to be with words. Using imagery allowed me to play, experiment and conceptualise my difficulties without having to expose myself to such vulnerabilities.’

Looking at Daniel’s imagery is not easy. Certainly, the lights in darkness might act as metaphors for hope, but the beds trigger memories of hospitalisation. And then there are the images of self harm – cut limbs, protruding rib cages – repellent yet, at the same time, grotesquely appealing, for those who know the temporary comfort such abusive actions can bring. Aware of the twisted mindset of fellow patients, Daniel is consciously careful not to show images that he feels may be too triggering. ‘But the reality – my reality – is that I have scars that are healing and showing this was important to me,’ he says. ‘I am a person with mental health issues as much as I am a person of mixed heritage or someone that likes the colour red. It’s just a part of me. I find great inspiration in these experiences, much as a rambler may feel inspired by the landscape. I can’t imagine myself as anyone else. After all, as Oscar Wilde said: be yourself; everyone else is taken.’

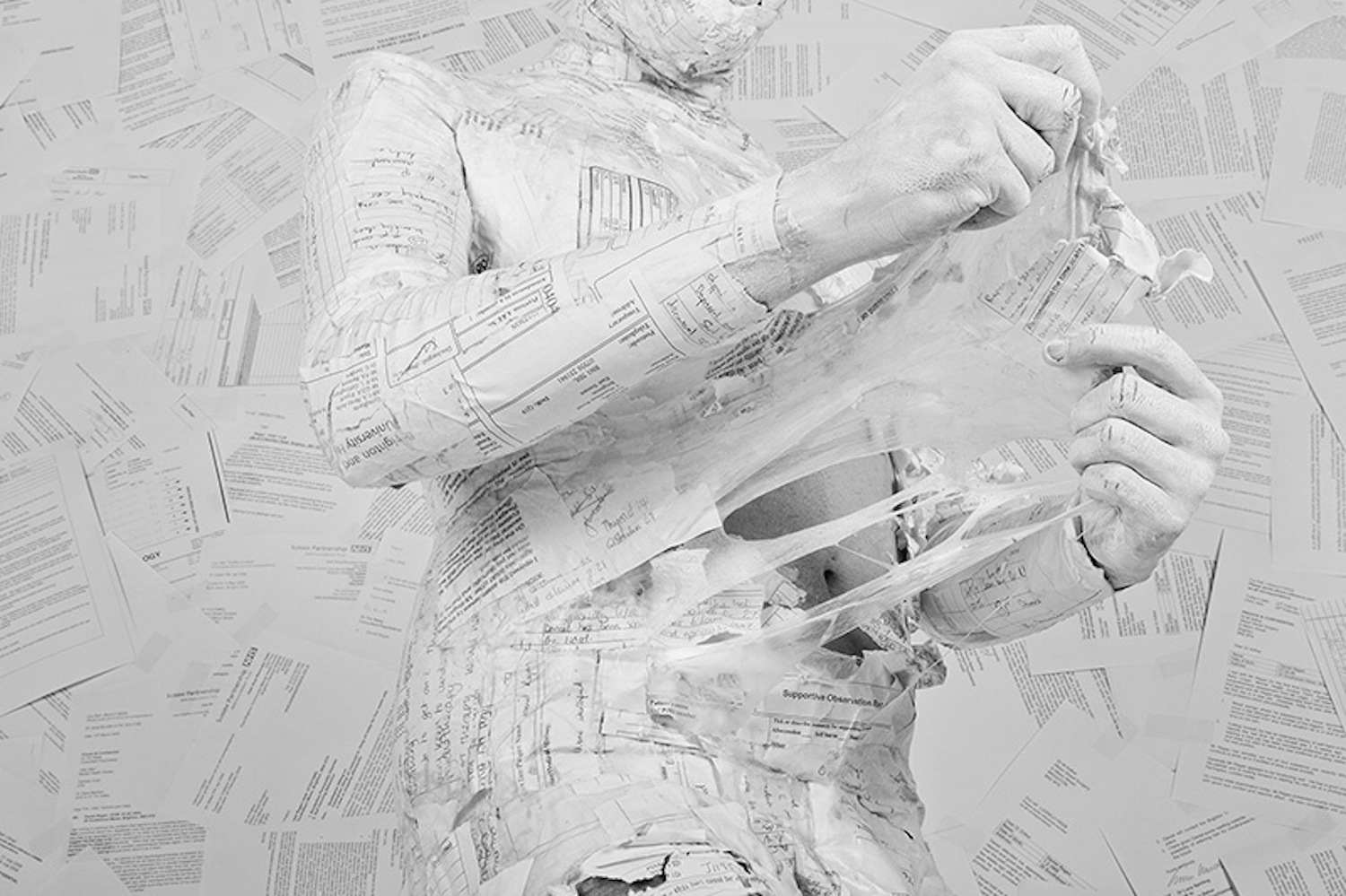

Daniel’s most recent project, Fragmentary, was completed for a residency at Kentish Town Health Centre. In it, he digitally combines scans of his mental health medical records from 2003-2009 with self-portraits he took at the time. He explains, ‘There are certain pages from the records that really resonate with me for various reasons. However, I felt that displaying the record in full was too revealing. I often teeter on the fine line of over- and under sharing. I redacted parts of documents that were too sensitive for me to share and then, finding a self-portrait taken on or around the date of the document, inserted the texts into the archived digital JPG code. It creates a shift in the image, a corruption, and was, for me, a way of amalgamating differing perspectives on a very difficult time in my life.’

The image Shell (2012), for which Daniel wallpapered his body – and his studio – with his medical records, before peeling them off in front of the camera, features in both Insula and Fragmentary. ‘I often think of living with mental illness as living with a second skin. Here it felt freeing to pull it away, peeling away layers of chaos.’

My own medical records, so it seems, got lost when I moved GP surgeries a few years back. How this can happen, when everything is digitised, I do not know. As a result, I often feel angry and frightened, as if my entire existence up to that point – with its battles against various life threatening illnesses, both physical and mental – has been erased. Forgotten by those in control, it is as if it never happened. Only I know it did – and I am still living with the ever-unfolding repercussions. I feel my identity has been compromised; my suffering denied. Those notes, inaccurate as they might have been, were proof that I existed, that I am here, that I am real. In this, I can understand why, for Daniel, taking photographs is so therapeutic. They capture the moment and document his existence.

In Fragmentary, Daniel reclaims his history – as seen through the eyes of others – and juxtaposes words with images, diagnoses with symptoms, facts with memories and feelings with thoughts. Photography can freeze the visual moment, but it’s not yet clever enough to take a snapshot of the frazzled, fluctuating mind. If it could, however, I think it would look just like this – words, images, spliced together and shaken up, distorted, incoherent. All the parts are there, the jigsaw could hypothetically be completed, but something prevents this from happening. Should recovery strive to build a whole or should it simply set about embracing the fragments and the broken nature of an, at times, tortured soul? For me, there is no doubt that it can only ever do the latter.

As Daniel says: ‘I think art is an integral way of representing difficulties that often cannot be explained. Thoughts and emotions do not come in cookie cutter moulds and artistic freedom allows people to express that which they cannot find another language for. I find that by sharing my difficulties it prompts dialogue around mental health, allowing others to talk openly about their experiences and breaking down mental health stigma and taboos.’ I hope to have added to that dialogue. Please let it continue.

Copies of Insula are available on Daniel’s website

Daniel Regan was selected as one of four emerging photographers to participate in Evolving in Conversation which began during Brighton Photo Biennial 2014 continuing through to May 2015.

Evolving in Conversation is made up of three interrelated project strands all encouraging greater participation in arts and library activities throughout Brighton & Hove.

Daniel led a participatory workshop as part of World Book Night at Jubilee Library on 23 April. At the event, the library announced The Humans by Matt Haig as the book selected for the 2015 City Reads. This fictional account explores what it means to be human through the eyes of an alien and can be interpreted as a metaphor for the alienating nature of depression.

Photoworks have commissioned Anna McNay to write about Daniel’s work, an artistic and personal account of mental health, drawing out links between his work and wider mental health issues