Bill Brandt The English at Home

Text by Zmira Zilkha

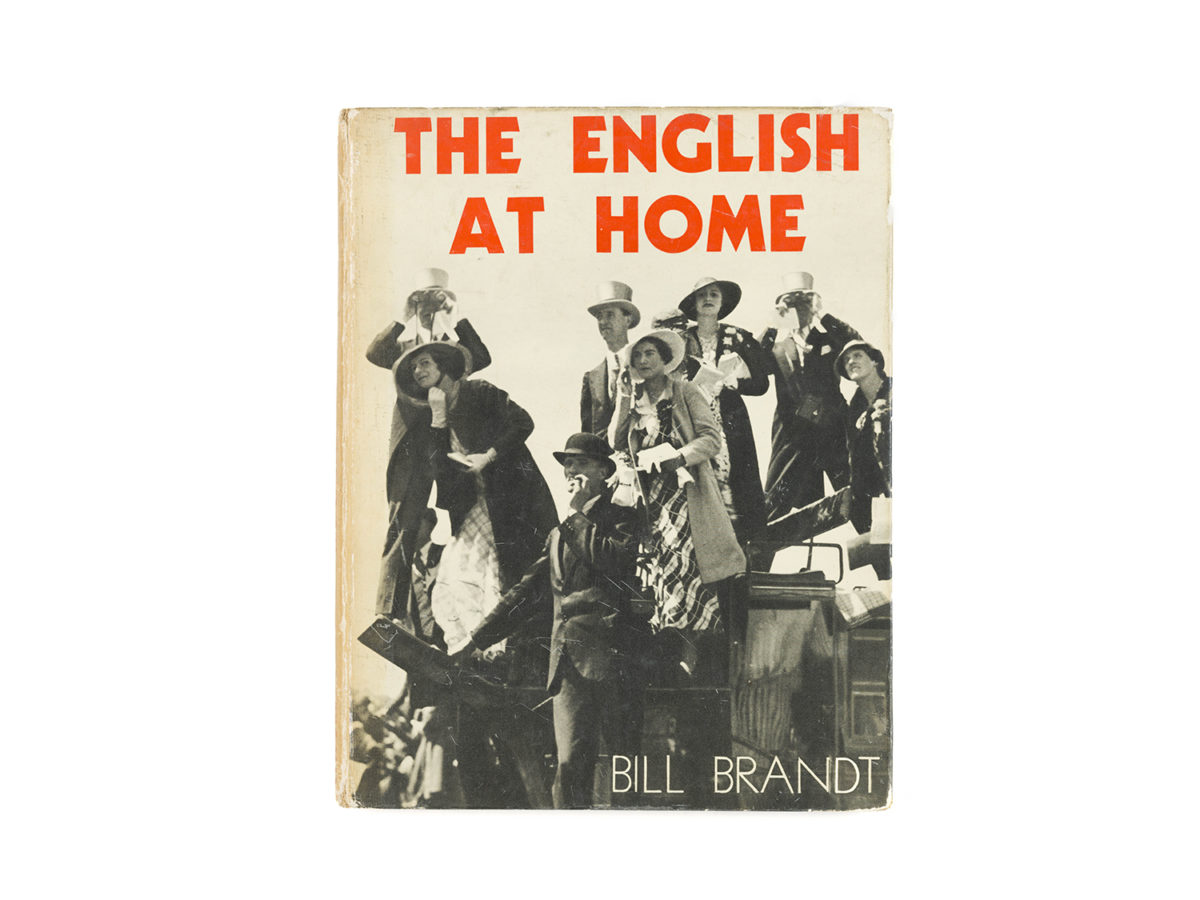

The early twentieth century saw several projects exploring how photography can be used to capture ideas of national identity. Perhaps most famously August Sanders’ Faces of our Time (1929) which focused on a certain time and place. Similarly Bill Brandt’s iconic 1936 photobook The English at Home is often acknowledged as one of the first attempts to photograph a nation. Brandt made the work in the years immediately after his arrival to England. He did not shy away from documenting the class structure he saw in daily life, emphasising the inequalities through his radical approach to editing. The English at Home was featured in the Brighton Photo Biennial in 2018; here writer Zmira Zilkha looks at the project in depth.

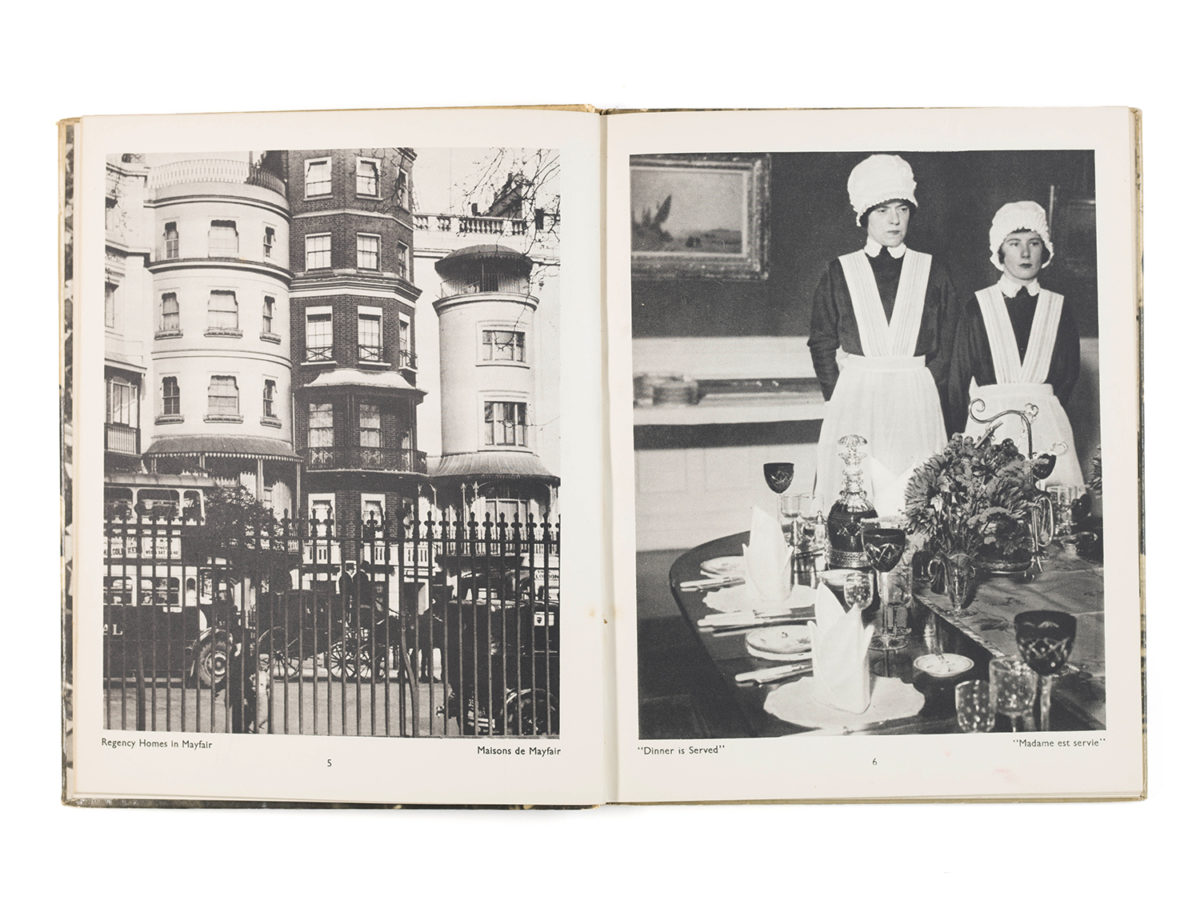

In the foreword to Bill Brandt’s 1936 book The English at Home, Raymond Mortimer describes the artist’s collection of 63 photographs as the result of German-born Brandt having ‘wandered about England with the detached curiosity of a man investigating the customs of some remote and unfamiliar tribe’. Perhaps enabled by his foreigner’s eyes, Brandt’s ethnographic study of his newly adopted country at once offers transparency and objectivity. His singular ability to simultaneously convey intimacy and distance continued to define his nearly five decades of photographic production. The English at Home, published by B.T. Batsford, presents an examination of England’s social class structure , from the everyday activity of labourers in the countryside to the extravagances of London’s aristocratic elite. Page by page, a cross section of English society, both urban and rural, emerges in atmospheric monochrome.

Born in Hamburg, Germany, to an English father and a German mother, Brandt relocated from mainland Europe to London in the early 1930s with his wife Eva Boros. He overtly disowned his native country in the wake of World War I, making Britain his home until his death in 1983. Brandt spent four years of his youth in Switzerland, where he stayed in two sanatoria to convalesce from tuberculosis. It was during this time of prescribed repose that Brandt, albeit casually, began to engage with the camera. His first professional training in photography, specifically portraiture, came in 1927 during an apprenticeship with photographer Grete Kolliner in Vienna. He moved to Paris in 1930, where he secured an informal position in the studio of Man Ray. The American artist’s prominent role in both the Surrealist and Dada circles, which encouraged spontaneity and dismissed “rationality”, as well as his attention to printing and manual editing processes, awakened Brandt’s appreciation of the mundane in the photographic image. Bolstered equally by his admiration for Paris-based photographers Eugène Atget and Brassaï, Brandt’s modernist sensibility took shape.

The English at Home, Brandt’s first published photographic book, marks the artist’s application of his Parisian influences in the pursuit of a largely documentary-driven practice. While the content reads, on the one hand, as photojournalistic reportage intended to illuminate the socio-economic divide that afflicted interwar England, Brandt maintains his Surrealist inclinations on the other by depicting each scene as fragmentary and vague. However it is unclear whether Brandt’s visual commentary is intended as radical provocation or factual documents of everyday realities. Inspired by his own curiosity and “anthropological” interests rather than a commission, the project saw the artist traverse the country in search of subjects as archetypal representations of England’s social hierarchy. His extended family’s wealth and connections gave him unique access to key parts of the country’s varied demographics, which allowed him to create a far-reaching portrait of daily life.

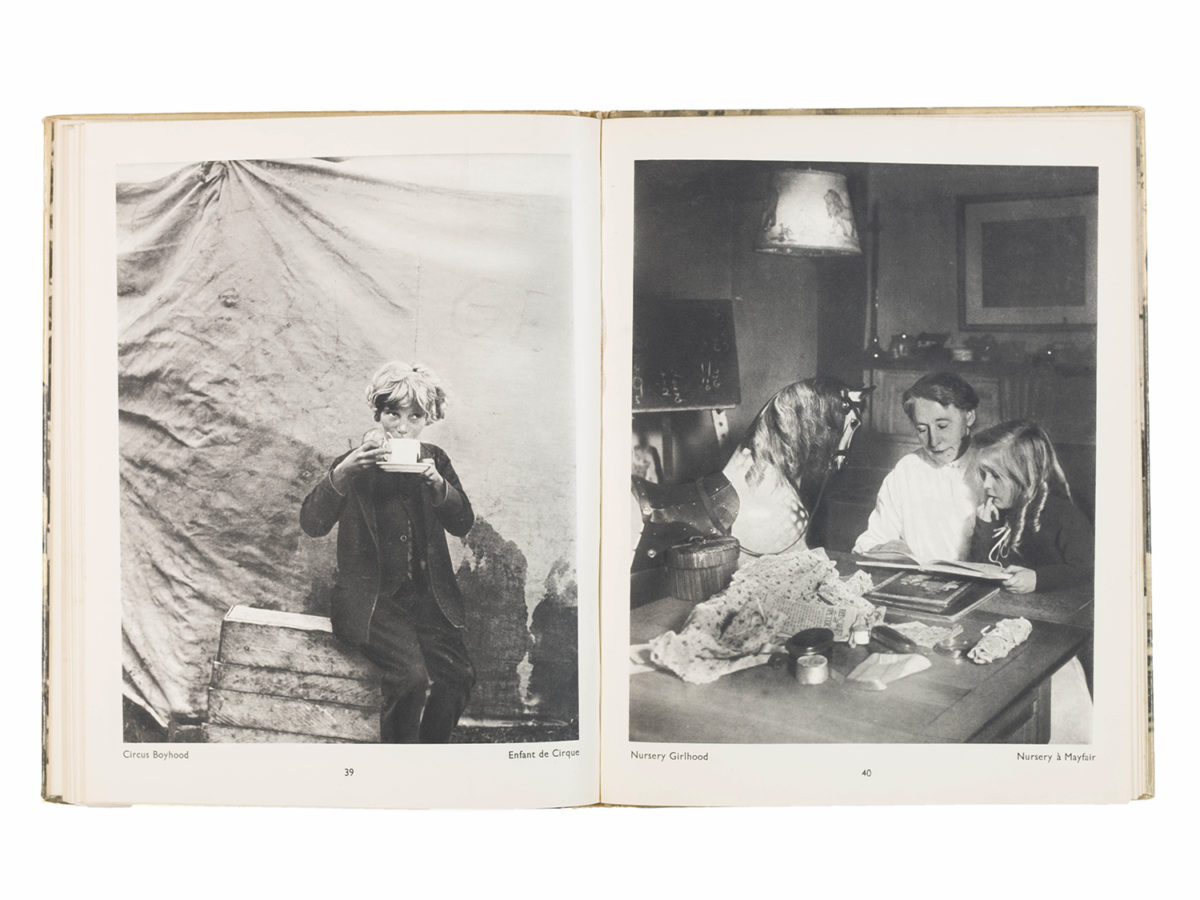

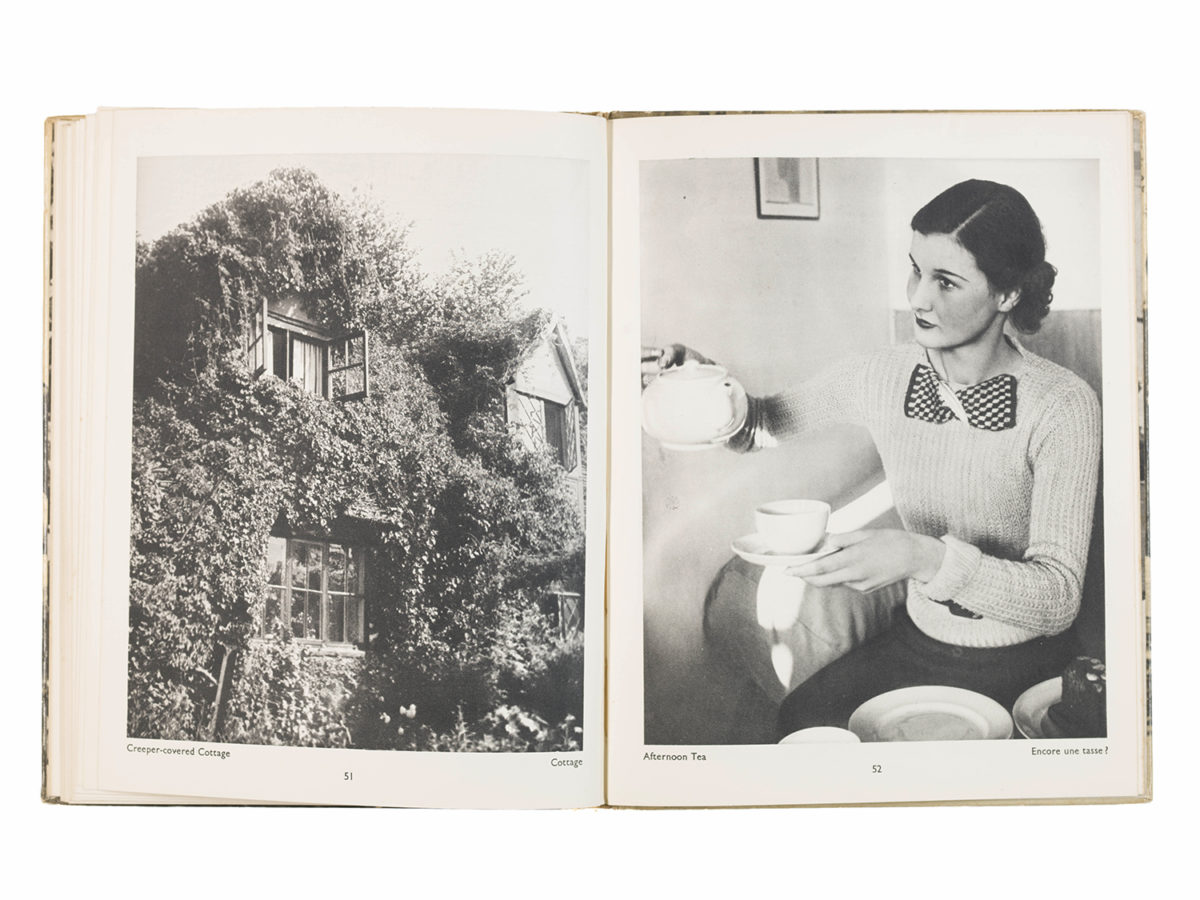

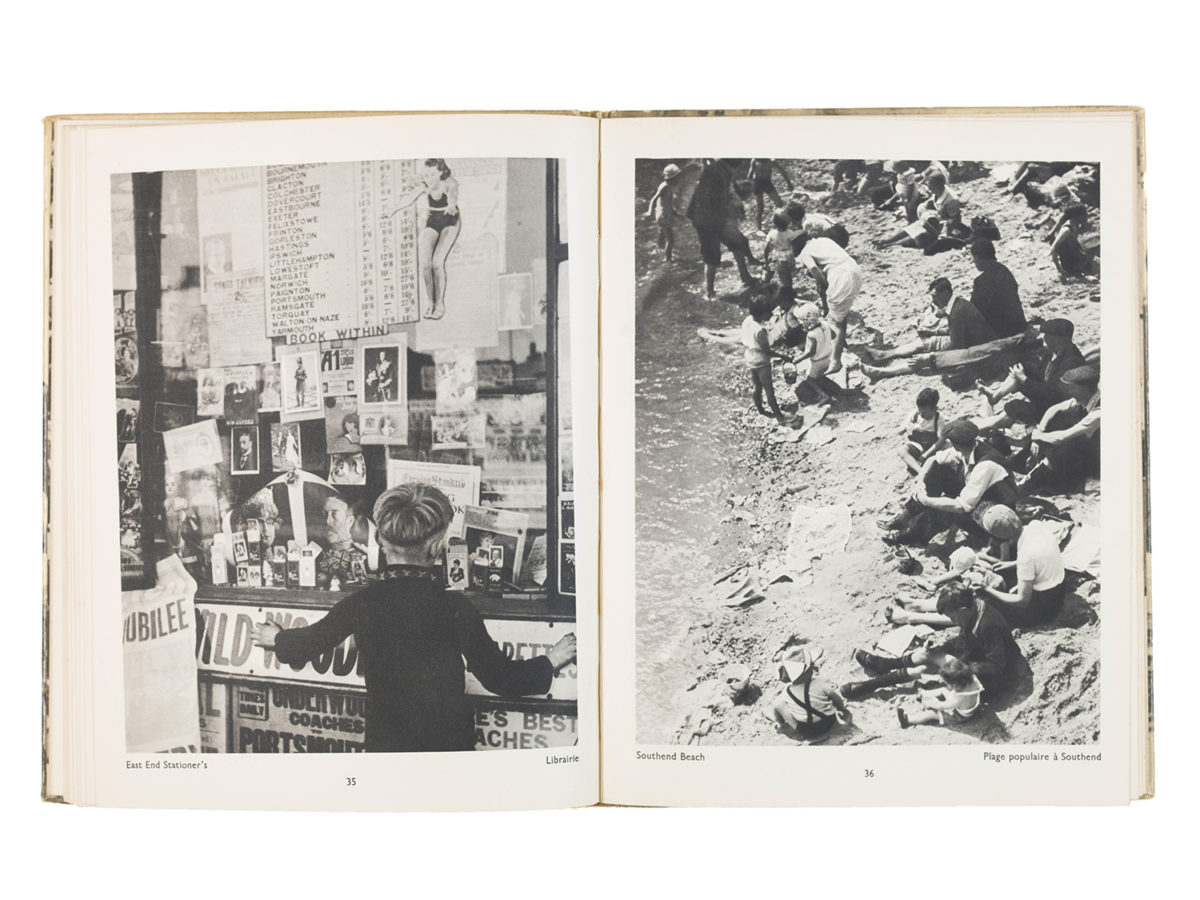

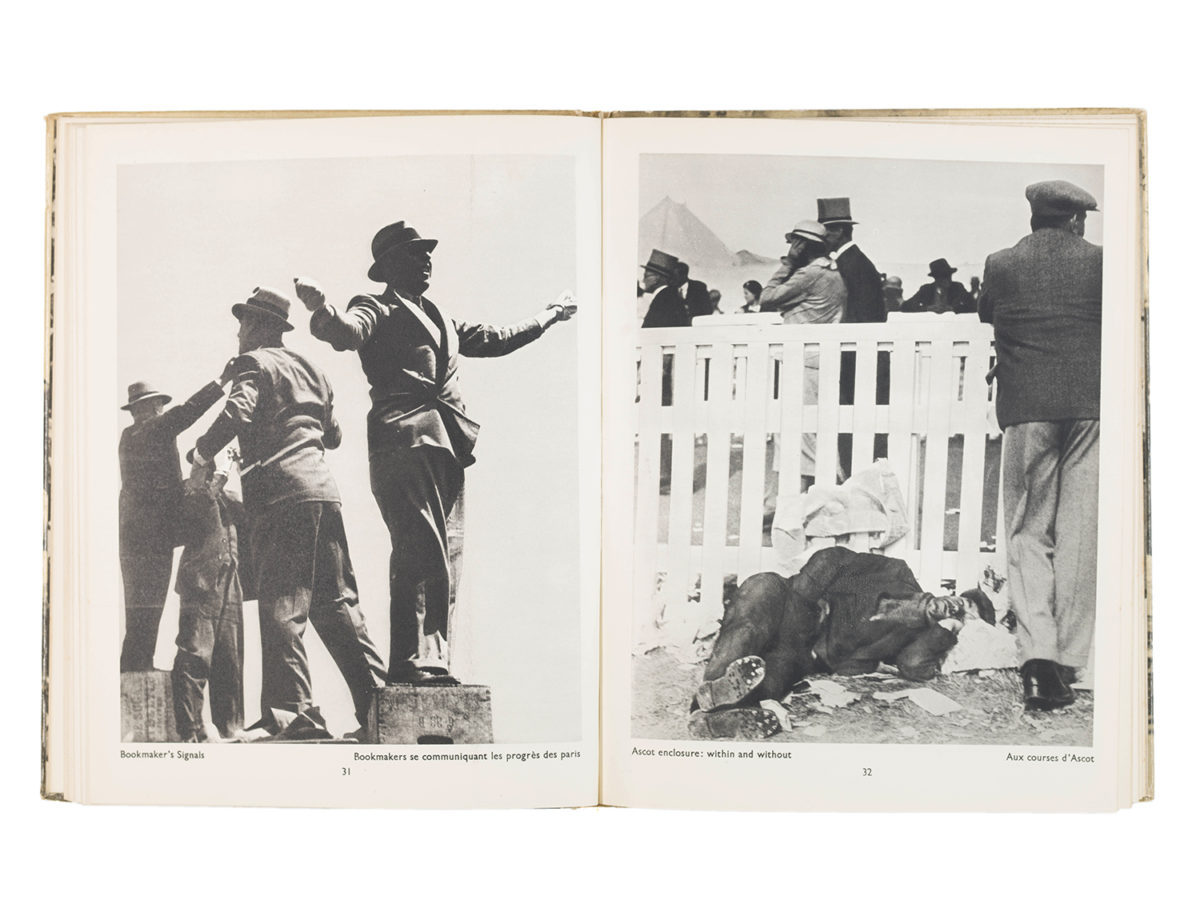

Rather than using the sequential narrative often associated with the photoessay, Brandt structured his book as contrasting pairs; many of the two-plate spreads contain one image of the upper class, and one of the lower. Every juxtaposition – say, between a working men’s restaurant and a gentlemen’s club – invites the viewer to question the status quo. One particularly striking pairing is ‘East End Playground’, a candid glimpse of children playing in the streets, and ‘Kensington Children’s Party’, which features well-groomed toddlers mingling in a sitting room filled with sumptuous fabrics. The gritty pavement and imposing angles of East London’s working-class terraced houses contrasted with the rosy cheeks, manicured haircuts and balloon decorations create a dissonance that is both formal and thematic. Throughout The English at Home’s photographic pairings, icons of British culture appear; miners, aristocrats, parlour maids, and ladies at afternoon tea animate its pages.

Brandt’s foreignness, as alluded to by Mortimer in his foreword, undeniably informed, and perhaps accounted for the aesthetic success of The English at Home. His ‘detachment’ allowed him an unvarnished and unobstructed view of the nation to which he strove to belong. Brandt’s aptitude for objective observation continued throughout his prolific contributions to popular publications including Lilliput, Weekly Illustrated and Picture Post in the 1930s and 1940s. His relentless capture – and, at times, staging – of the social realities and dynamics of all walks of life established his status as the foremost documentarian of mid-century Britain. Revered for his voracious exploration of the camera’s descriptive capacity, which he would later explore in his highly stylised and abstracted nudes, Brandt remains a pioneering force, a precursor to the strong tradition of British documentary practice which flourished in Britain in the latter half of the twentieth century.

For more from issue #1 Europe click here.