Dead ends

Text by Claudia Lynch

‘Architecture immortalizes and glorifies something. Hence there can be no architecture where there is nothing to glorify’.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Like many places the Berlin Wall now exists in people’s consciousness largely through photographs. It was captured from countless viewpoints over the course of its existence, and these images depict both the Wall itself and the history that it symbolises. Each set of photographs tells a slightly different story, shaped by the focus of the photographer and by the time in which the images were made. Although immovable, the Berlin Wall was by no means static: it grew in strength and size during the almost 30 years it stood for. And like a contagious disease, its presence spread into the parts of city it cut through. Yet by 1989, when it was physically at its strongest, its ideological foundations had been so weakened that, in retrospect, the toppling of the Berlin Wall seemed like an inevitable conclusion – although that wasn’t necessarily apparent at the time.

In August, 1961, British photographer Don McCullin travelled to Berlin to capture the construction of the Wall. By the time he arrived, the barbed wire fence that had marked the border initially had already been replaced by concrete blocks topped with barbed wire.

and that it was only lightly protected by barbed wire.

© Don McCullin/Contact Press Images

and that it was only lightly protected by barbed wire.

© Don McCullin/Contact Press Images

McCullin’s photographs show the physical feebleness of this wall, its banality as a piece of construction – barely a foot thick, not high enough to prevent eye contact between people standing on opposite sides, gaps in the mortar joints allowing glimpses through. Yet it was already impenetrable.

The focus of McCullin’s images is not the Berlin Wall itself, but rather the people on both sides, who can still be captured in the space of a single frame, their incredulity, bewilderment, and curiosity apparent. Some images show how life in West Berlin (the side where the photos were taken) continues close to the Wall, whereas the civilians on the eastern side had already been replaced by border guards. Some of these guards, perhaps unsure of their new role, even seem to be engaged in conversation with people in West Berlin, as if the Wall were a mere garden fence.

In the mid 1960s, when Harry Shunk and János Kender travelled to Berlin, the Wall was in the process of evolving into its next incarnation: a structure of concrete slabs supported by steel girders and concrete posts. Its presence had spread physically, and had started to affect the city around it: windows in nearby East Berlin housing blocks were bricked up to prevent people jumping out, and parts of buildings were systematically removed to create more space around the Wall and to make room for further security measures on the eastern side. Watchtowers had been erected. Tram tracks stopped dead against the Wall, and weeds started growing from the cracks. A timber cross was erected in West Berlin to commemorate the people who died while attempting to cross the Wall. A raised platform was created for West Berliners to see across the now much taller Wall.

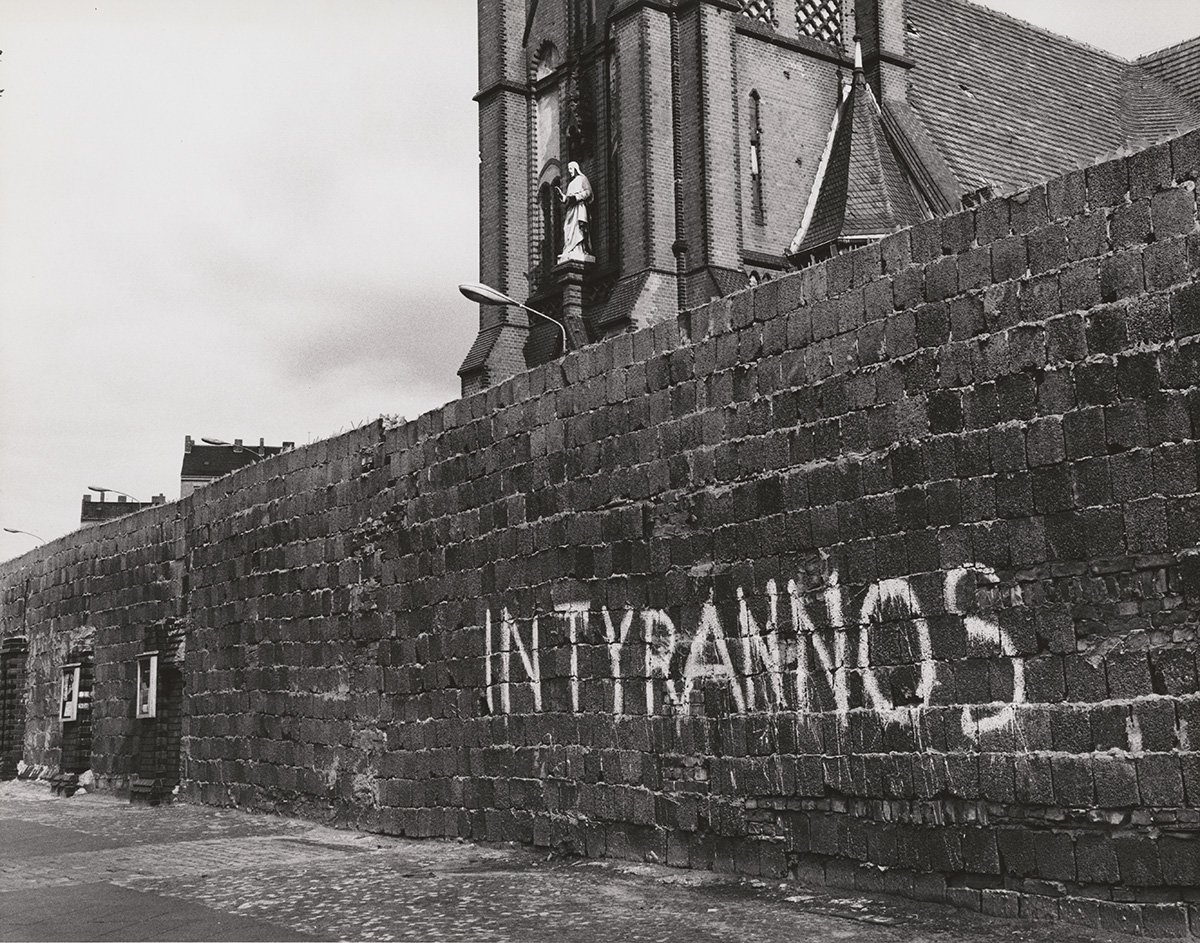

Shunk-Kender’s photographs focus on the physicality of the wall. One image from 1965 shows the Wall on Bernauer Straße, which formed the border between the French Sector on one side of the street, and the former Soviet Sector on the other. ‘IN TYRANNOS’ is painted on the western face of the Wall in big letters – an indictment of the dictatorial nature of the GDR. The space behind the Wall is dominated by the Church of Reconciliation, which was completed in 1894. The Church was damaged during World War 2, but had been repaired in 1950. Its nave stood in the Soviet Sector, but its main west gate faced the French Sector, and before the Wall went up, its congregation comprised Berliners from both sectors. In August, 1961, the western façade of the Church of Reconciliation was incorporated into the newly built Wall, and the western gate was bricked up, shutting out West Berliners. By October, the Church had been incorporated into no man’s land – what became known as the Death Strip – which meant that East Berliners were also prevented from entering. Border police began using the Church’s tower as a watchtower, and as a machine gun base. In 1985, 20 years after Shunk-Kender made the photograph, the GDR ordered the demolition of the church, tearing down a symbol of urban and national unity.

The family of photographer Michael Schmidt family moved from East to West Berlin before the Wall was built. Schmidt lived his life in Kreuzberg, in the shadow of the Wall, and in 1980, he began a series of photographs of the urban landscape of Berlin, Berlin Nach 45. ‘I could also make photos somewhere else; I just wouldn’t know why,’ he explained to an interviewer. By 1980, the Berlin Wall had been further enforced: it was made of concrete slabs nearly four metres high, and the no man’s land, which was more than 100 metres wide, included trenches, electric fences, patrols, dogs, watchtowers, minefields, and a second inner wall on the eastern side. Looking at Schmidt’s images, the viewer feels as if they are backing up against the Wall. The Wall itself is hardly visible, but its ever-expanding presence can be felt. Schmidt described himself as a ‘photographer of dead ends’, and his images are dominated by vacant, dismal foregrounds, spaces that feel abandoned – as if life has moved elsewhere (proof of which can be seen in the new buildings visible in the far distance).

A different type of wall features prominently in the photographs: the fire walls that separated adjacent housing blocks. These walls were left exposed when the rubble of bombed buildings was cleared after World War 2 – gaps in the city that, despite the Wirtschaftswunder of West Germany, no investor was tempted to fill. Kreuzberg, which was once in the centre of the city, had become an isolated periphery. Although Schmidt’s images were made in West Berlin, it is difficult to tell which side of the Wall they depict. The emptiness, boredom, and desolation evoked by the images were a familiar experience in the East.

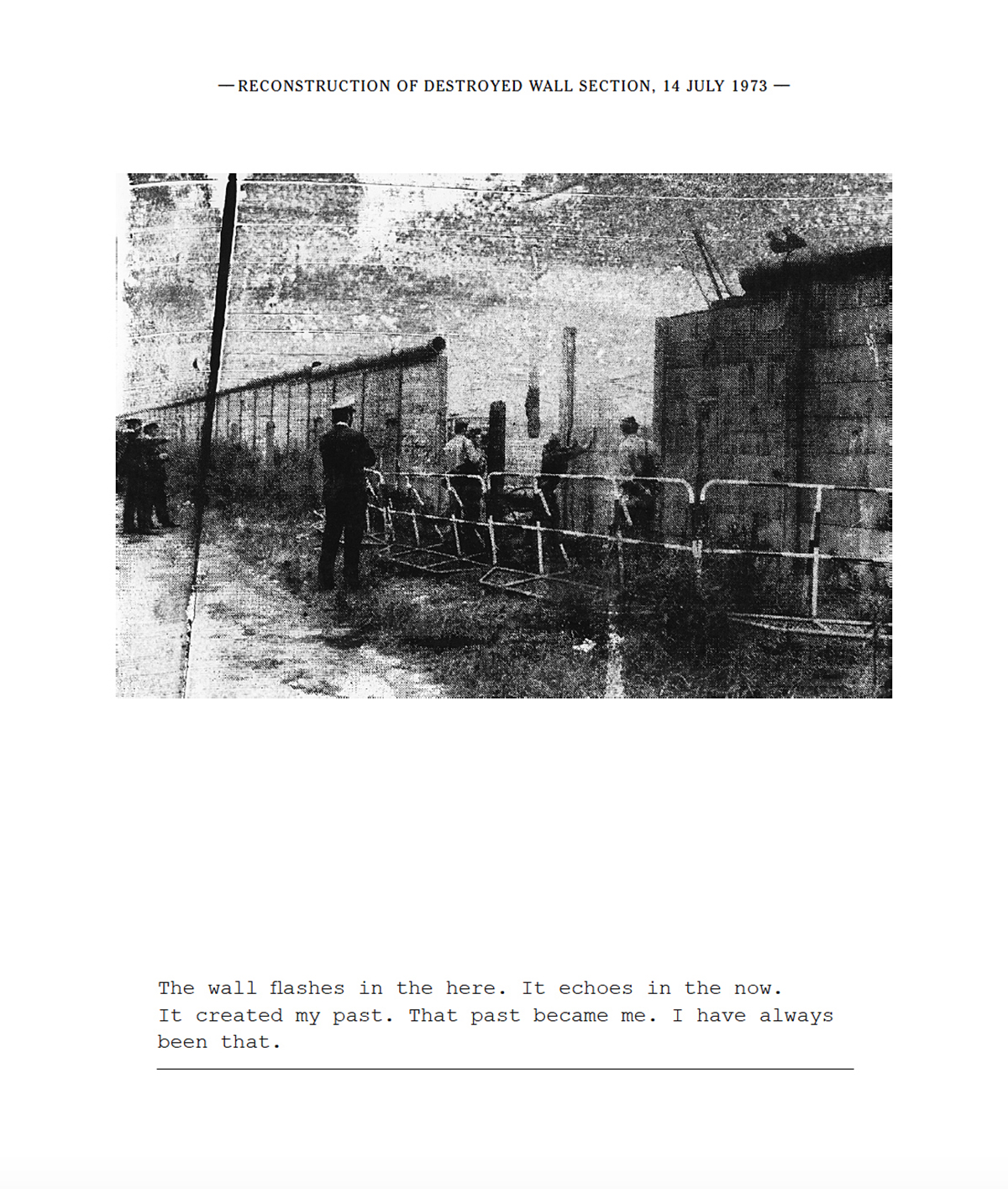

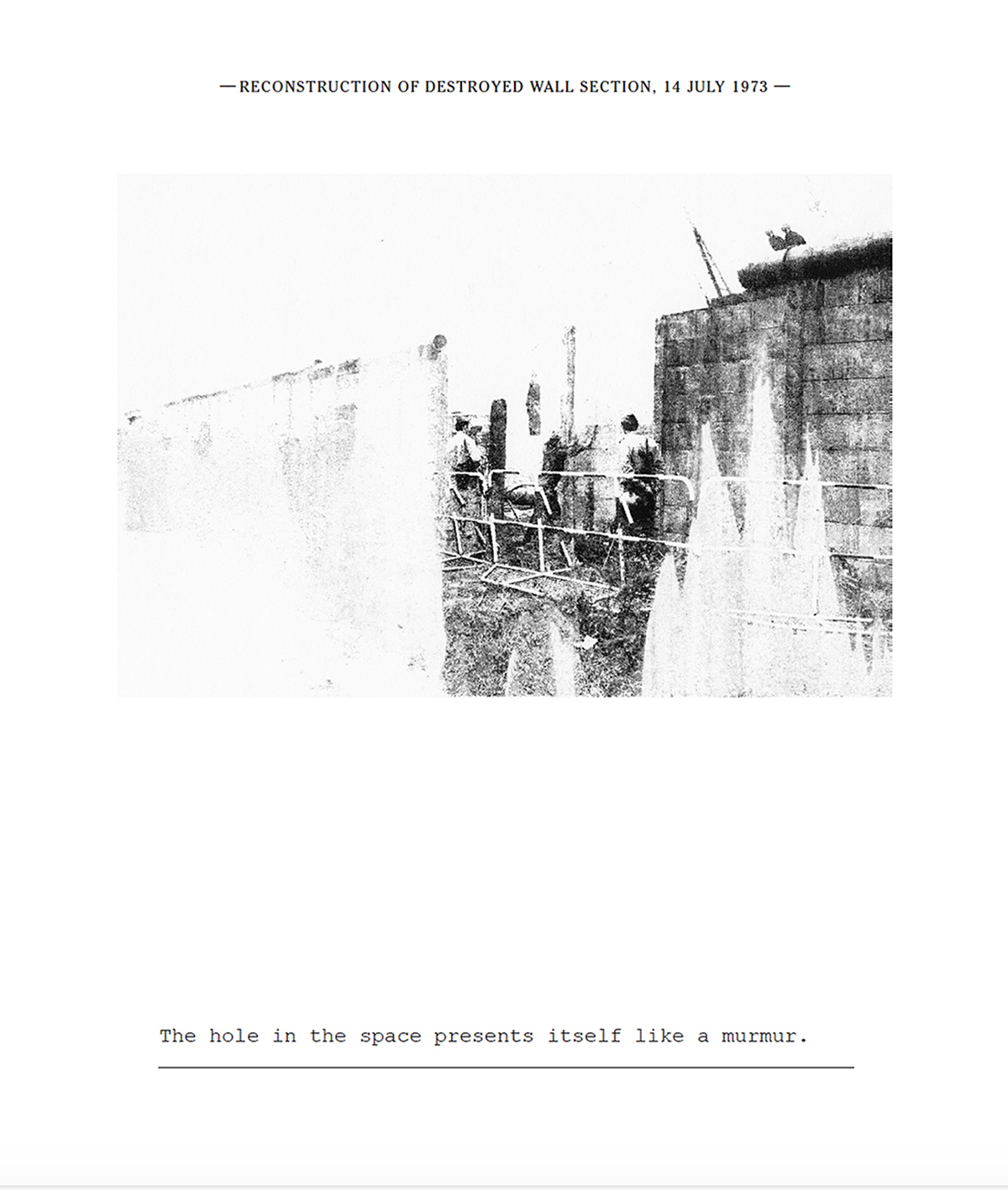

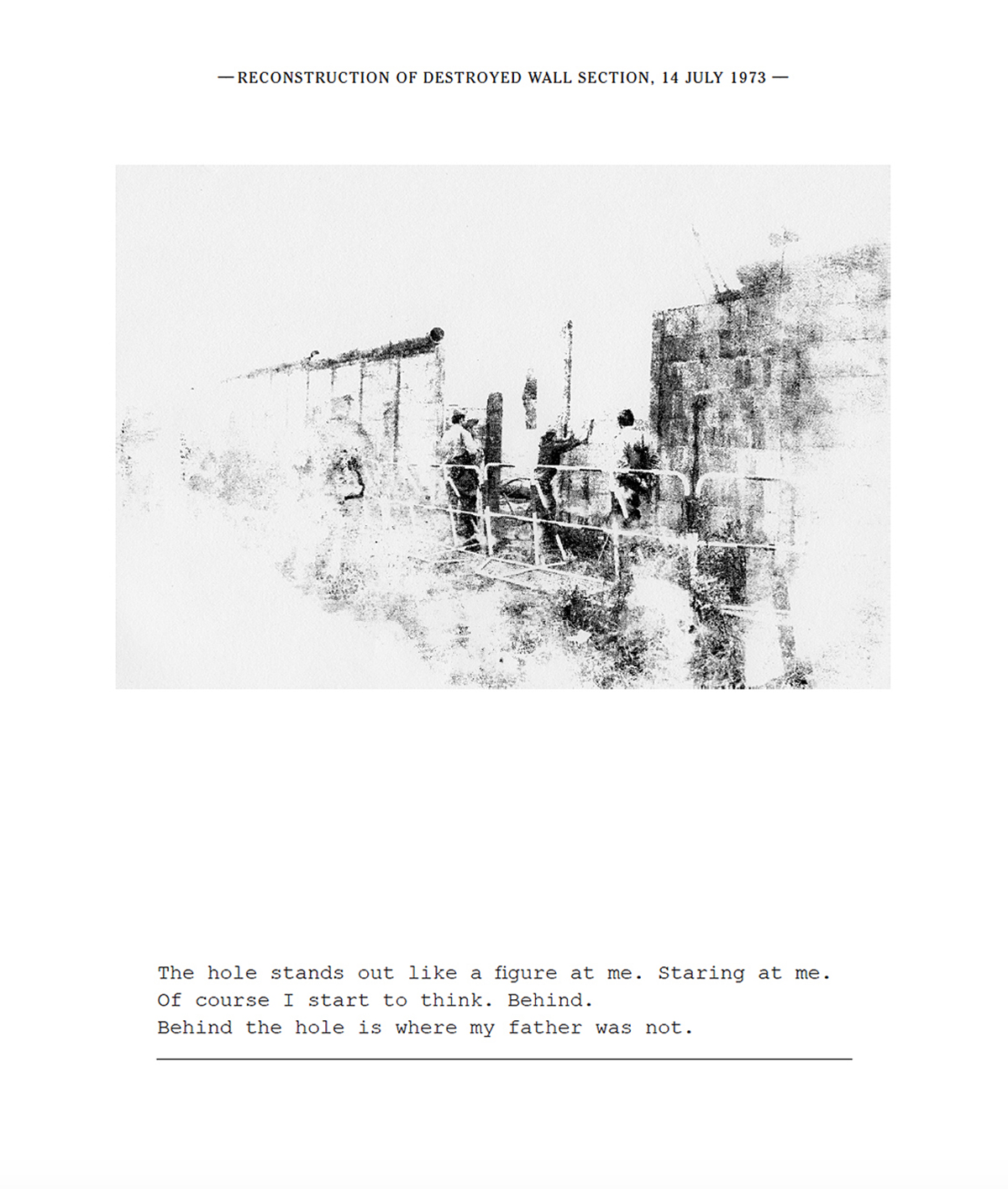

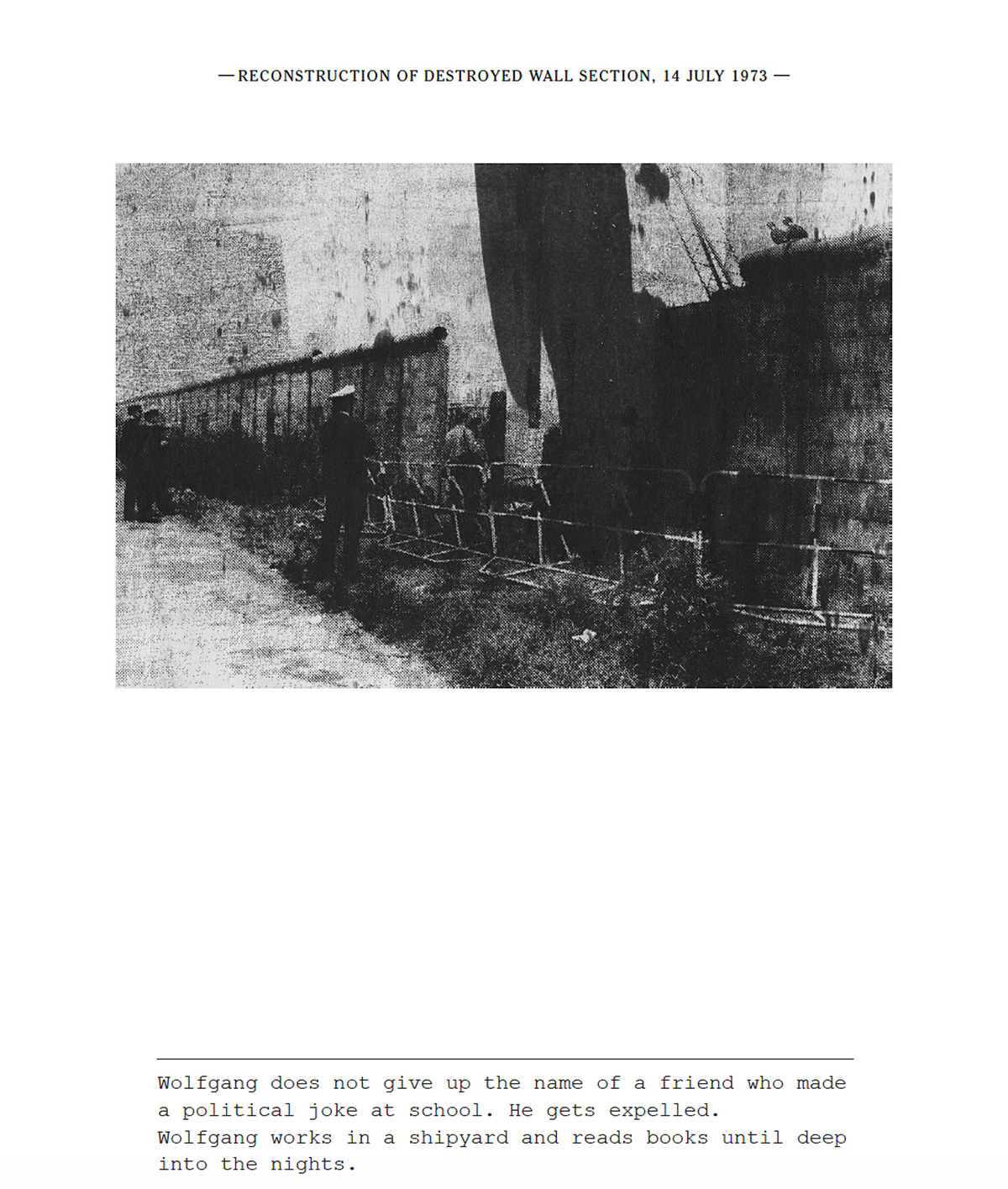

Photographs of the Wall from the eastern side are rare. Simply carrying a camera near the Wall could be construed as preparation for escape – or worse, espionage – and could result in imprisonment. Photographer Steffi Klenz, who is now based in London, grew up in the north of the GDR, roughly 250 kilometres from Berlin, but her parents’ life and her childhood were shaped by the Wall and what it represented. Her 2016 series, He only feels the black and white of it, is based on a found press photograph from 1973, in which a hole in the Wall is being repaired by East German soldiers. The hole was made by West Berliners, who were angered by the sound of shots being fired at people attempting to flee the GDR. Klenz reproduces this image as a number of unique screenprints, each one paired with a fragment of text that relates to her father’s inner and outer life. The photograph is distorted by the screenprinting process, and although the prints record a fact, a moment in time, they seem open to interpretation. Yet, ultimately, through repetition and the accumulation of brief insights into the life of Klenz’s father, a story eventually emerges that shows how inconsequential even a substantial hole can be – no one passed through it to the other side – in a wall held up by tyranny and guns.

Claudia Lynch is Director of Lynch Architects. Lynch studied architecture at T.U. Dresden 1990–5 and at The University of North London 1995–7.

Read more Photography+