Text by Photoworks writer-in-residence Marissa Chen.

In the 2009 novel Important Artifacts and Personal Property From the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry, writer and illustrator Leanne Shapton (born 1973) artfully chronicles the life and death of a New York relationship in the form of an auction catalogue. The auction takes place, brutally, on Valentine’s Day. The items for sale – the couple’s personal possessions – are shot in greyscale, their descriptions similarly cold and clinical. (Shapton engaged a Sotheby’s employee to proofread the novel for tone. From the debris of a once-shared life emerge details about the couple’s jobs and families, what they ate (takeout menus) and how they ate it (discarded kitchenware). The reader watches them row silently (via back-and-forth scribblings on playbills), and discovers their code for initiating sex (a McGill Athletics t-shirt, apparently).

The novel is ‘sort of about how reliant we are on our things to define us,’ Shapton told the New York Times. The story of Lenore and Harold’s doomed romance is one everyone will understand intimately, but what sets such stories apart is their trail of ‘private meaning … those kinds of things that mean everything to the person who owned them and nothing to anyone else’. So it is that even Lenore and Harold’s most emotionally charged items acquire a type of rigor mortis, become low-contrast and colourless through the utilitarian lens of the appraiser.

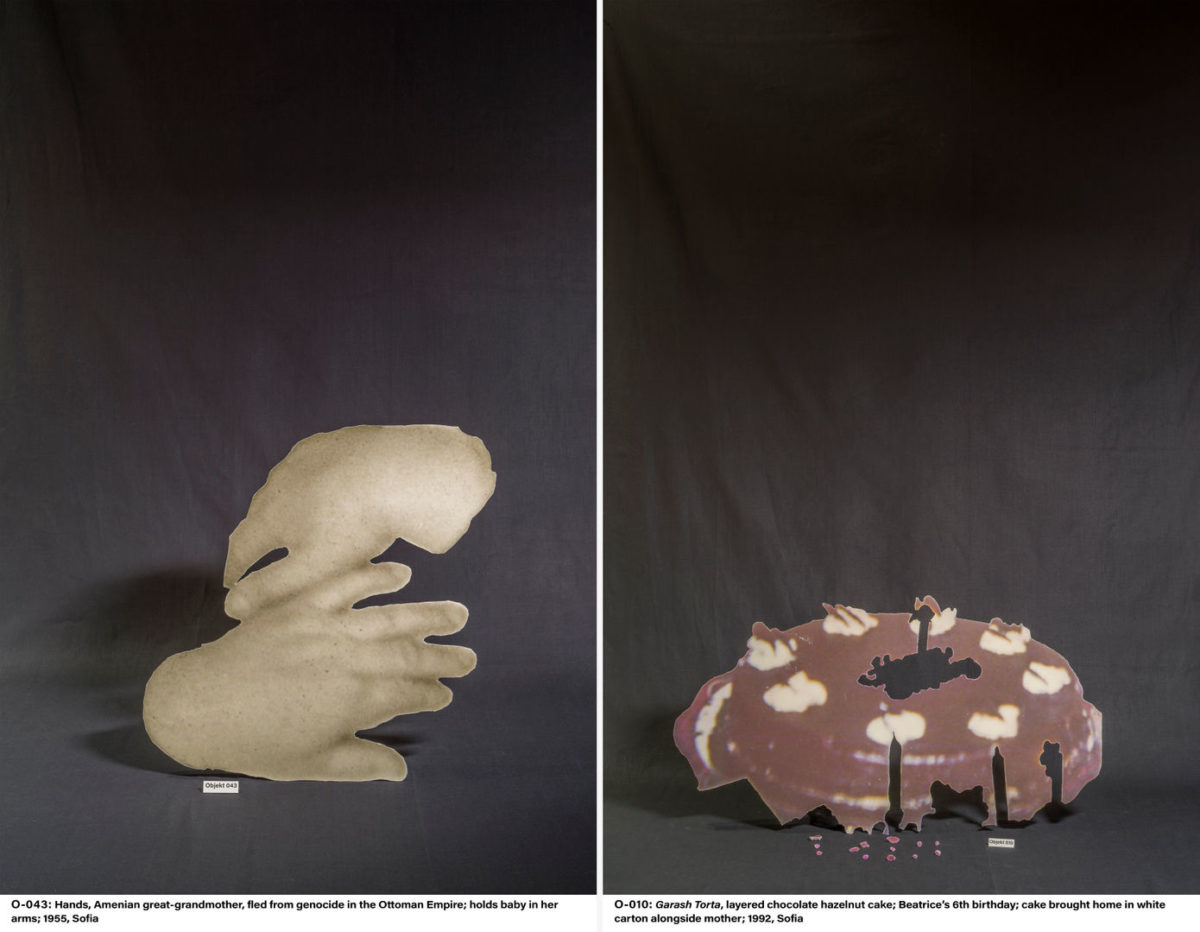

When people vanish from our lives, we often engage in the undignified act of conjuring plausible fictions from the objects they leave behind. In Forensic Excavations Inventory or the Total Deconstruction of an Eurasian Family (2020), Sofia-born visual artist Beatrice Schuett Moumdjian (born 1986) uses a combination of photography, collage and text to fill in the gaps in her migrant family’s history against an equally fraught political backdrop of socialist totalitarianism in Bulgaria, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Armenian genocide and more.

Moumdjian’s story, like Shapton’s, is told primarily through images of objects, pared and decontextualised from family photographs, many of which were taken before her birth. Presented in the style of museum artifacts are not only household ephemera – Objekt 063 (a newspaper clipping) or Objekt 791 (a Barbie pop-up playhouse) – but also body parts: a pair of dark eyes, kid-sized knees, the head of a favourite cousin, the ‘widest nose in the family’. Moumdjian mounts the cutouts to create an impression of three-dimensionality, an ode to the transformative power – yet tender futility – of memorialising loss.

The sequencing of Forensic Excavations Inventory is ruled by disorder, not chronology, to reflect the lives that have been broken apart by intergenerational trauma. ‘The way the story is spun across unrelated objects, in a non-linear way, reflects how trauma memory is formed,’ explains Moumdjian. ‘The body, at the time of the traumatic chain of events, is unable to cognitively process the event, so the emotions of fear or sadness, terror or loneliness are stored in the brain and body at various spots, not linked to the actual event that one might remember.’

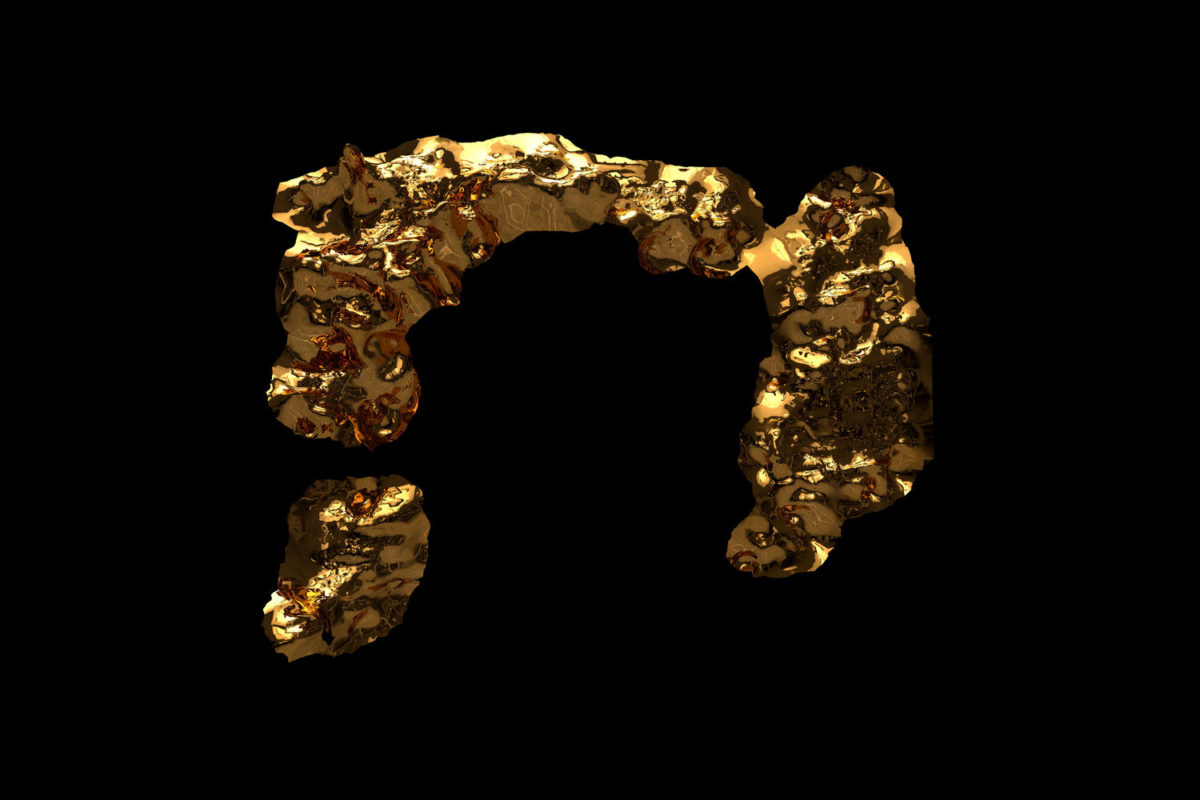

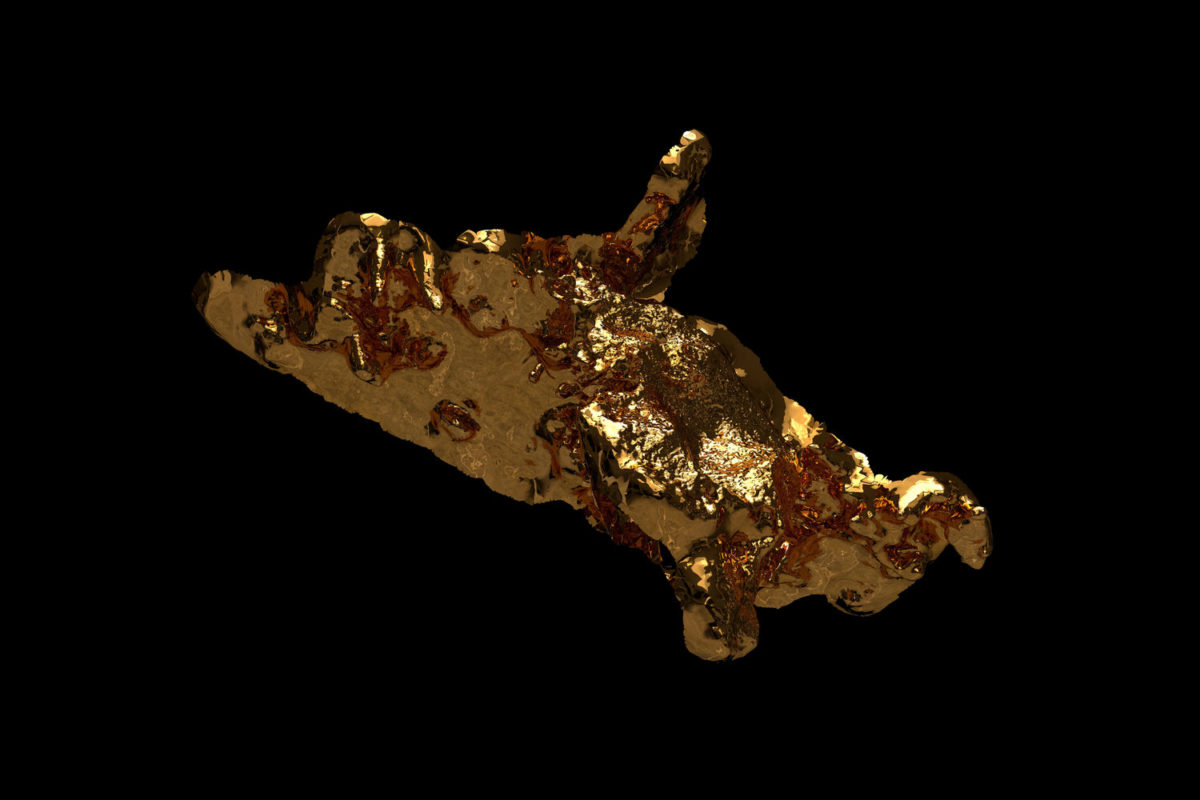

In Midas (2020) by recent London College of Communication graduate Wojciech Feć (born 1997), what began as ‘an act of preservation and archivisation’ became a study of how memory holds up in an increasingly digitalised world. Using photogrammetry software, Feć created iPhone scans of toys, knick-knacks and other objects found in his childhood home until ‘they no longer resembled their physical counterparts’, instead becoming disembodied sculptures seemingly ‘rendered in gold’

Unlike the chilly objectivity of the auction catalogue, the individual studies that make up Midas are entirely abstract – it is nearly impossible to deduce the original contents of Feć’s archive. The project is less concerned with what memories tell us than with what they do to us. ‘Human memory is imperfect and entropic, just like how files get corrupted and magnetic tapes degauss,’ Feć says. In Midas, the erroneous glitches produced by his scanning process become a crucial tool of mark-making that transforms memory into the most precious commodity there is.

But, just as gold has a tendency to corrupt, our defining memories are often those that cause the most pain. In the Greek myth, Midas was originally thrilled with his ability to transform anything into gold; he suffers for his hubris and starves after realising that he is no longer able to eat or drink. An obsession with the past can overwhelm the present, rendering us unwilling or unable to break the bonds of memory’s calculating spell. Are there some histories that might be better kept under glass, safely out of reach?

Shapton’s fictitious auction ends in the way of most real-life romances – with listings for one-room apartments, corks from spent bottles, a bunch of dead flowers. As much as the reader has learned about the intersecting lives of Lenore and Harold – the only two people who could have made complete sense of this cabinet of curiosities – there are still endless questions. What was the story behind the heart-shaped iced-trays, or Harold’s half a wishbone? Would the relationship have survived without them?

One by one, we turn the objects of memory over and over, so in their long shadows we might someday arrive at the closest versions of the truth. But perhaps this dogged pursuit of objectivity really is one of hope – for a portal to a different ending from the one that has already taken place. The works of these three artists might first read like a lament for lost time, but they also extol the freedom that comes not with looking back, but in finally looking away from what once was. ‘Individual objects can be points of reference for many different people,’ says Moumdjian. ‘Through the objects and the telling of my particular connection to them I enter people’s stories, and they enter mine.’

Learn more about the graduates

Beatrice Schuett Moumdjian Wojciech Feć