Nadia Yahlom, 24 October 2025

In her 1993 landmark novel Memory in the Flesh, about a love affair between a young woman writer and her father’s friend, Algerian novelist Ahlam Mosteghanemi writes: ‘Is paper a dustbin for the memory, a place where we always deposit the ash of the last cigarette of nostalgia, the remnants of the final disappointment?’ It is all too easy to think of women’s stories as dustbins of memory: devalued, crumpled into balls, and institutionally dumped. But it is exactly this tension – between what is deserving or undeserving of preservation – that plays out in Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie (the Archive of Women’s Struggles in Algeria).

Originally formed by social scientists Saadia Gacem, Awel Haouati and Lydia Saidi[1], it is an audio visual and textual account of Algerian women’s roles in organising, protesting, advocacy, education and militant resistance, particularly centred on the late 1980s and early 1990s, one of the periods of intense political struggle that followed independence from French colonialism in 1962. The archival project itself arose out of a two year popular uprising: the 2019-2021 Hirak movement الحِرَاك (sometimes known as the ‘Revolution of Smiles’) which continued after the removal of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika. The films, newspaper clippings, photographs, receipts, posters and interviews that comprise the archive emerged not from state-held and museum collections, but through the collective’s tireless efforts to retrieve items of national importance, unsurprisingly consigned to women’s private collections. The ‘archivists’ traced many of their items by contacting activists via protests or over Facebook. The collection now stands at over seven hundred items. It is a tribute to women’s assembly: not only in documenting women assembling in different ways to demand change, but in placing these varied movements together in recognition of their collective contribution to a period of radical change in Algeria. An archive not formed organically (as some seem to be) but created. A labour, as it were, of radical love.

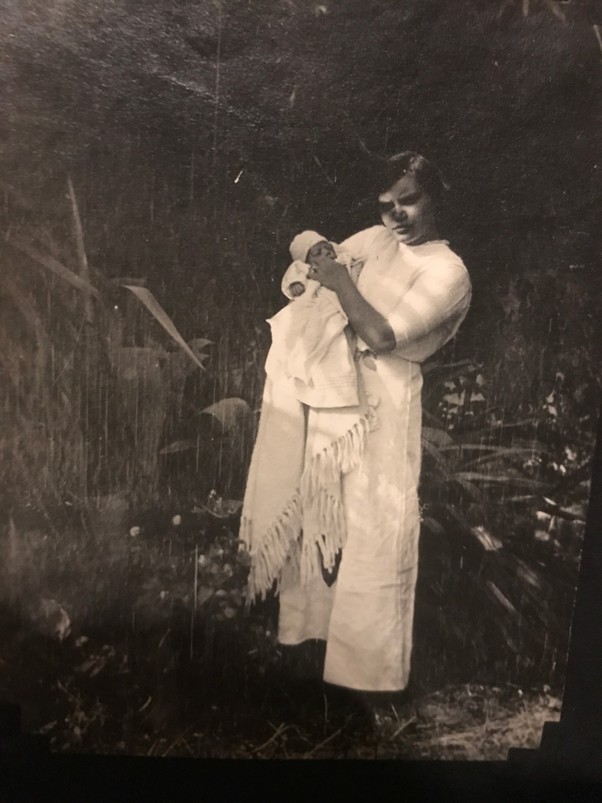

Long before I understood what archives were, I was surrounded by them. My father – Palestinian Jewish and born under British rule in Yafa – has always been a fastidious chronicler. I’ve seen perhaps one or two images of my dad as a child and a teenager. He, on the other hand, captured every moment of my childhood on camcorders, Polaroids, and the many rare film and later digital cameras he’d pick up at second hand fairs. Even at the cinema he would – to my immense embarrassment – routinely crouch down on the front row and photograph the audience. Drawings, toys, and other ephemera were also carefully filed and stored away, often chronologically. Nothing (and I mean nothing) was to be thrown away. He said this was the way to ensure we could remember (be remembered?).

My mother – no doubt exhausted by this and her own family legacies of archiving and accumulation – rarely ever took an image of us. Her maternal line was born and brought up in Hong Kong, and they had been avid photographers, including professionally. So, we have huge chests full of both studio portraits and candid images taken at home, during trips to Malaysia, Egypt, and many other places. For my mum, everything played out in the moment without the need to physically archive it. Family lore would be recalled in rich, vivid detail by her, a gifted storyteller, years later. A child of the Sixties and an avowed feminist who had lived in Palestine, Cyprus, Japan, America and elsewhere, stories of female emancipation, of anti-colonial liberation, of socialist struggle and of protest, abounded. These were as much a part of my childhood as any of the books I was read at bedtime. This was her approach to assembly.

Out of these dual legacies I became an artist, working with images, film, poetry and fiction — often preoccupied with absences produced by episodes of catastrophic violence, with ways of reimagining archives and recentring women’s stories. I’m now in the process of completing a PhD about the Palestinian supernatural, which looks at how colonial violence leaves its imprint on people, places and objects.

In the midst of this phase of the genocide (since October 7th 2023), making, speaking and writing feels both futile in the face of such a cataclysmic war machine and necessary, because this behemoth aims to destroy not only Palestinian lives and land, but memory. Many of us have watched daily as men, women and children have been murdered, vapourised by bombs, burned alive in tents, shot by drones, beheaded by falling masonry from their own homes, or left to die slowly under the rubble of collapsed buildings. But we have also watched the deliberate destruction of things that comprise the larger Palestinian ecosystem. We have seen the bombing of museums, historic sites, archives, libraries, archaeological ruins and collections, and all of Gaza’s universities. And with this, irreplaceable parts of Palestinian cultural heritage, of folklore, ritual and religious lore, storytelling and history, much of it dating back to hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

[1] Lydia contributed significantly to the collective between 2021-2023 but is no longer active in the project.

Tracing women’s archives of resistance

In light of this, to witness, to archive, to document and to assemble in acts of individual and collective resistance is not only urgent, but existentially vital. It is in this spirit that I turn to the Algerian women’s archive. Walter Benjamin, at once a literary theorist, philosopher and collector of ruins, spoke about the ‘aura’ of individual artwork dissipating in an area of mass digital reproduction.[1] The aura that radiates from Archives des luttes is not based on the aesthetic distinctions of individual works, but on the archival gaze: the collective, unbroken female spirit. The women painters included are framed in terms of their contribution to designs for political posters rather than their artistic achievement. Gone is the monumentality of the museum artwork – with all the grandeur of beautiful, holy relics displayed behind glass, translated by curators. In its place are scraps of lives lived, and rights hard won, and the archaeological remnants of different women’s work: fragmentary and profoundly human.

The colonial and the patriarchal gaze in all its many forms have consistently robbed Algerian women of agency and of a proper place in the archives, including the ability to return, subvert and redirect that gaze. French colonials often applied photography as an instrument of power, the camera lens serving to aestheticize its crimes against the Algerian people, with lushly rendered images emerging from the front as it meted out the most egregious forms of bodily punishment against men, women and children: torture, dismemberment, mutilation, rape and murder – crimes that were never seen (and were routinely denied) by the French government, media and public.

During this period, in the 1960s, soldier Marc Garanger was responsible for photographing Amazigh and other girls and women arrested and placed in concentration camps. Over the course of ten days, he took two hundred ID photographs per day: ‘The women had no choice in the matter’, he later said. ‘Their only way of protesting was through [the look on their faces].’[2] There is a dangerous allure to the pictures: the beauty of the women belying the fact that they have been forcibly unveiled, their elegant attire and jewellery, kohl and protective facial tattoos not proudly displayed but photographed under duress. Women assembled not in radical struggle but herded together as detainees.

In the Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie, women are transformed into architects of their own destinies: active and engaged. Unlike in so many chronicles of popular uprisings, they are not presented as accessories to men’s resistance efforts, but as the main protagonists of a period of social and political transformation. Some of the most powerful images in the archive are nonetheless windows into the unshowy, thankless acts of resistance that women are so often associated with, which underpin and sustain political movements, and which rarely make it into newspapers or end up immortalised. A lone woman standing on a street handing out political pamphlets and newspapers encouraging women to organise and defy a new electoral law permitting husbands to vote in their wife’s place or a protestor at a demonstration carrying her sleeping toddler.

It is the candid intimacy and humanity of these snapshots – a world away from the grandiosity, severity and machismo with which male resistance figures are so often shown – that is most moving. Women can be seen laughing or in conversation, arms linked at protests or leaning on one another during a film screening. The patriarchal notion that these moments were not worth chronicling – that resistance should be stoic at all times – was no doubt part of the reason they were not properly archived in the first place, not until the collective began painstakingly assembling them (and the stories associated with them) by tracking down and interviewing the women activists featured. The archive affirms that what men see as our weakness has always been our strength: our ability to foreground our humanity, our fallibility and our emotions. To present ourselves as living, breathing, feeling entities and as intersectional beings who can incorporate multiple identities: fighters, mothers, thinkers, radicals, wives, artists, activists.

In several of the images, we see women protestors smiling, bearing banners calling for the emancipation of women, the very embodiment of a new generation of Algerian feminist. It is rich both with utopian possibility and the relaxed naturalism presumably born of consent (at being photographed). It is an entirely different defiance to the kind shown by women coercively documented and archived by Garanger a few decades earlier: the joyousness, friendship and sisterhood born of assembly emerging as its own distinct form of resistance.

In Tell Your Tale, Little Bird,[3] a 1993 documentary which recounts the experiences of seven Palestinian women involved in the liberation struggle, they reflect on their roles as members of the armed resistance. Whilst they recall the torture and abuse they experienced in Israeli jails at the hands of their captors, they also laugh. At one point, one of them jokingly describes almost drowning whilst trying to cross through water during an operation and having to be pulled out by a male comrade. For the male resistance fighter, this sort of account would never make it into the triumphalist annals that define how men monumentalise their achievements and are monumentalised by others in a global patriarchal system that requires men to be strong, unfeeling and unyielding. In this documentary, as with Archive des Luttes, humour emerges as a badge of honour and pride.

The histories of Algerian women’s struggles are inextricably linked to the Palestinian liberation movement – a deep-rooted affinity between both peoples that continues to this day (borne no doubt from mutual anti-colonial struggle and the warmth shown to the PLO and other Palestinian resistance movements by Algeria). Several images in the archive reflect this. It is for this reason that the collective had some of their materials withdrawn in 2022 from Germany’s authoritarian clampdown during the documenta fifteen and became the target of baseless accusations of antisemitism.[4]

Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie is a deeply inspiring and powerful testimony to a deliberately obscured history – one half of the making of a nation. The work that these women researchers have done to preserve the stories, images and film has itself become an act of political resistance – a statement of refusal to be relegated to the margins and the footnotes of history, or the ‘dustbins of memory’– an insistence on being seen on their own terms. Long may it continue, from Algeria to Palestine and beyond. In our archives and images yes – but also in the stories we bear. In our drive to assemble. In our refusal to be forgotten or, worse still, erased.

***

This article is dedicated to all those chroniclers, storytellers, journalists, artists, photographers and archivists – living and dead, surviving and martyred – who have created in the face of annihilation.

[1] Benjamin’s concept of aura, famously developed in his 1936 essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, remains central to debates on art, authenticity and mechanical reproduction.

[2] Carole Naggar, ‘Women Unveiled: Marc Garanger’s Contested Portraits of 1960s Algeria’, Time Magazine, April 2013, https://time.com/69351/women-unveiled-marc-garangers-contested-portraits-of-1960s-algeria/.

[3] Arab Loutfi, dir., Tell Your Tale, Little Bird, 1993; Egypt: Cinema Maa.

[4] The controversy centred on their inclusion of visual material from a 1988 issue of the Algerian feminist journal Présence de femmes, which had devoted a special feature to Palestine. That issue included powerful illustrations by Syrian artist Burhan Karkoutly and Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali depicting Israeli acts of aggression. The collective’s statement in response to the witch hunt was unfailingly articulate as it addressed, and debunked, the accusations one after another. That they should have had to defend themselves was absurd.

This essay was originally published in Trigger 6: Assemblies (November 2025), the first volume in Trigger’s new annual book series from FOMU – Museum of Photography (Antwerp) and Fw:Books. Guest editor Taous Dahmani turns to the SWANA region (Southwest Asia and North Africa) to explore how gatherings—formal or informal, loud or quiet—are always politically charged. Bringing together photography, personal essays, and archival material, Assemblies redefines what collectivity can mean today and tomorrow. Nadia Yahlom’s contribution appears in the book’s archival section, which resists the logic of spectacle and highlights the radical power of everyday assembly as rehearsal for other possible worlds.

Co-published here with Photoworks as part of their edition on ageing, Yahlom’s essay on women’s assemblies (Archives des luttes de femmes en Algérie) speaks to intergenerational memory, resilience, and the transmission of political experience across time.

Nadia Dina Yahlom is a Palestinian-Jewish and British artist and visual anthropologist, looking at hauntedness, supernatural life and the bio/necropolitical between Palestine and the UK. Her research and practice considers how humans, artefacts and landscapes reverberate with colonial violence.