Not much of the photography ever carried out in Britain can be classed as purely British photography. There was, though, a national movement of some consequence during the 1930s.

British Photography: Some Pointers

The names associated with it are those of James Jarche, Edward Malindine, Reg Sayers, Harold Tomlin and George Woodbine. They worked for the Daily Herald, a newspaper inclined to the Left and owned by Odhams, which also set up the story magazine, Weekly Illustrated, in 1934. They were populist photographers who could turn their hand to anything: the distressed areas, royal tours, the plight of fishing, a day at the races. Photography was never as central to the culture either before or after – partly because it had a lot of the field to itself at that time. Between them, Jarche and his associates projected an image of the British as indomitable and good-humoured participants in the national pageant. They took it for granted, more or less, that British life was a contrivance and that they were among the impresarios. They often, for example, photographed each other in action taking pictures of ‘news in the making’.

William Gaunt, the sketch writer and illustrator, called the tendency ‘Anglo-Dickens’, in honour of the writer himself and of his illustrator Phiz. By far the most successful actor in the British pageant was Winston Churchill, got up as an impresario in his own right in a Homburg and a cigar, acting the part of a man in touch with the people, brick-laying and roof-tiling. The pageant wasn’t a harmless bit of fun, but a test, which could also be failed. Churchill could cope and he could thrive on stage, but there were others who couldn’t act the part with anything like the exuberance required in the circumstances: Chamberlain and Halifax, tentative at Heston airport in outfits which made them look awkward, didn’t pass the photographic test.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

British news photographers were experts in the vernacular. They were participants in the show and came into daily contact with all those spivs, toffs, tipsters, bookies, pitmen, ploughmen, whelk-gatherers, fish-gutters and assorted riff-raff who made up the national aggregate. There was never any possibility of re-making the national spectacle along modernist lines, for the old mummery was held in great affection. Not that modernism, along Soviet lines, was rejected out of hand, for it could be used as a foil: chorus lines of fish-wives and trawler skippers with the mien of pirates.

Why, then, is this photography, which could be considered a high-water mark in the history of the medium, scarcely ever mentioned? Probably because it doesn’t fulfil some of photography’s basic requirements regarding time and space. For a photograph to be recognised as such there have to be acknowledgements of time and space: cast shadows and dispersed elements of landscape and structure. In photography, it seems, there has to be an element of resistance from time and space if the picture is to have its guarantee. Too much time and space and the picture becomes a mere transcription; too little and it begins to look like a studio piece with shaky credentials. Jarche and the reporters were never photographers in this strict sense, and aligned themselves much more with music hall and with the graphic tradition as embodied in George Belcher and Pont, and indeed with Edward Ardizzone in the ‘60s and Bill Tidy in the ‘70s. The aim was to get the best characterization possible, with a minimum of extraneous detail, which would only be a distraction.

Mass Observation

The Pantomime mode, as devised by the Daily Herald photographers, ought to be thought of as a movement. It has some of the ingredients of a movement, in particular the realisation that something new is possible: in this case that the Savoy Operas, for example, could be pastiched in another medium. Jarche et al were able to tap into the exuberance of the British tradition, from Hogarth and beyond, and to make it available in a burgeoning mass media. There was never anything like it, nothing so successful on such a large scale, but it wasn’t strictly speaking photography, which is where Mass Observation enters the scene.

It must have been obvious to those in the know that national photography as practiced by the Herald offered a partial take on contemporary life, and that it was scarcely objective. Nor was it clear where it stood politically, for it was populist and myth-conscious, and in this respect at odds with the liberal documentary which was such a feature of the late Weimar Republic. Almost all German photographers, including the nationalists, were practicing liberals up to 1933. They dealt almost exclusively with local life, in kindergartens, pubs and in workplaces of all sorts, and included Alfred Eisenstaedt and Eric Borchert, the town and country representatives of the Berlin agency Pacific & Atlantic. The Weimar years, in retrospect, must have looked like a liberal utopia.

Then there was the example of ethnology, which was a British speciality at exactly the time the Germans were pioneering their liberal documentary in Berlin. Routledge published a famous series of books on ethnology, such as Pagan Tribes of the Nilotic Sudan, by C.G. and B.Z. Seligman, 1932. The ethnologists took close observation to extremes, and it was their example which inspired Mass Observation in its study of Worktown (Bolton) in 1937-8. Its sole photographer was Humphrey Spender, and his pictures were meant to complement texts made by the Observers as well as reported speech collected on the streets and in the workplaces of Bolton.

The idea was that daily life empirically considered was interesting in itself – an idea at odds with the myth-making of the Herald reporters. Another premise was that speech was at least as important as appearance, and quite a number of Spender’s pictures are of people in conversation. To ideal audiences made up of ethnologists with time on their hands these reports must have been fascinating – and they remain so. The observers reported on pubs, where they weren’t always welcome because some of the clientele were on benefits. In these pubs the Observers were interested in the business of ‘drinking level’ which was a way groups had of keeping to a steady pace when ‘rounds’ were being bought. The Observers tested their theories on blind drinkers, who also seemed to have the knack of ‘drinking level’, almost as if it was a second sense possessed by the British. If the Herald reporters worked at a national level, using traditional materials, Mass Observation was local and even micro-cultural which really disqualified it from use in the mass media, where its findings would have seemed trivial in the context of world news. Nevertheless, Spender and the Observers did investigate the possibilities of the ultra-attentive documentary, and one, moreover, which required native speakers if anything worthwhile was to be gained.

Metaphors

Spender’s style at Mass Observation was never a viable option in the wider world. It was painstakingly objective and geared to the careful practices of ethnologists; nor was it appropriate to the propagandistic demands of the war effort. The war, as you would expect, altered the course of photography. In addition to everything else it was a sustained lesson in geography: previously unremarked Pacific islands, the wastes of the USSR, the coastline of North Africa and oceans everywhere.

Its principal indirect effect was to stress the need for international understanding and co-operation, and photography would play an important part in this new era – summed up in the great Family of Man exhibition of 1955. Where Mass Observation had assumed the importance of native speakers and of local knowledge, the new humanist photography of the 1940s and after was carried out by foreigners, in particular by Westerners reporting on Africa, India and the Orient. They didn’t speak the language, nor did their audiences, and the need anyway was to identify common denominators: a topic range which dealt with childhood everywhere, with hunting, agriculture, feasting and with all sorts of ceremonials. There was definitely no place for detailed disclosures, especially as they would have drawn attention to differences between the world’s cultures.

To be effective under these new terms of reference photographers had to find expressive and conclusive imagery which would relate to the topic range. As this range dealt with humanity at large it had to feature mankind representatively: children in relation to childhood, young people in terms of work and marriage. Audiences had to read such pictures for their major meanings, and one outcome of the tendency was to establish photography as an important medium internationally. It was part of the great humanist project, and that reputation clung to it well into the 1970s.

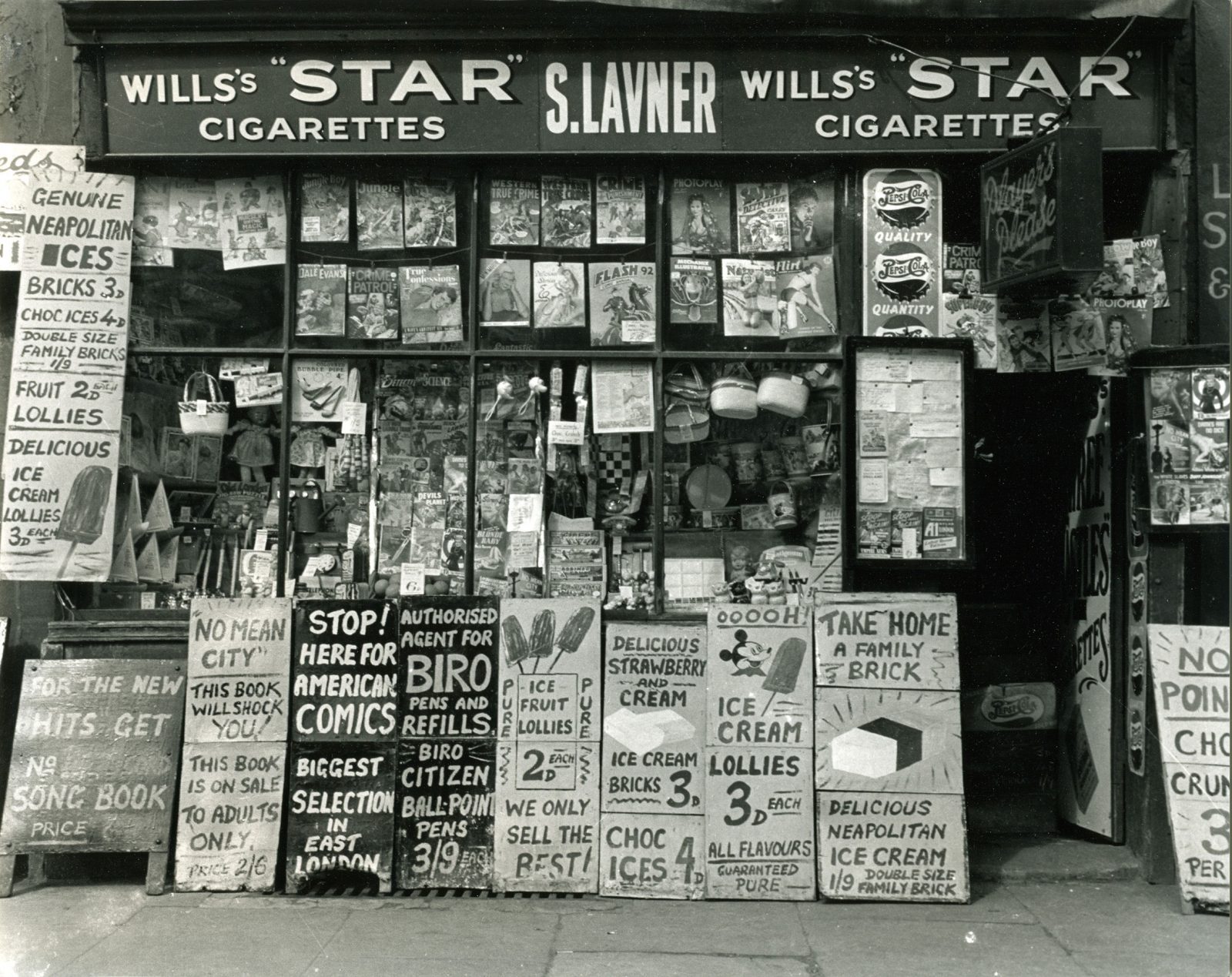

British photographers, however, had misgivings about the new aesthetics, especially if they were working at home. Any culture which you knew well couldn’t easily be treated symbolically as touching on the human condition, for from long experience you knew exactly what your subjects were like. It would be a travesty to represent them in any grand way and out of context. Far better, and more accurate, to present them as part of an environment along with the corrugated iron and Lyons tea adverts in which they had their daily being. This is a pointer to the British photography of the 1950s and ‘60s, of the kind so well presented in Martin Harrison’s Young Meteors of 1998. It shares quite a lot of features with Family of Man photography but eschews sentimentality and foregrounds mere appearance casually come up against in the street. It is a Britain which is recognizable (Woodbines, Capstan and Brooke Bond) but meaningless. It is not so far removed in appearance from Mass Observation’s Worktown, but in 1937-8 there was a guarantee that insight was to hand. You could, having read the texts, engage with the plight of Bolton’s washerwomen, for example, but on the streets of ’60s Britain you were exposed to casual encounters only.

The Herald’s reporters chose to imagine Britain staffed by boisterous archaics, who must have looked like the only people capable of coping with the totalitarian threat. The M.O. organization and Spender opted, perhaps nostalgically, for an ultra-liberalism, attentive to the minutiae of daily life. The new generation of the 1950s and ‘60s, probably more of a generation than a movement, wondered just what it would be like to be free of the obligations to understand and to sympathise which were so insisted on by the Family of Man. What would it be like to be shot of pathos for a while, and to be unrepentantly face to face with the unfinished surface of life? Exhilarating, of course, but at the same time disquieting, for without structure and meaning there could be no real satisfaction.

During the 1970s there were attempts to integrate structure into the informal modes of the 1960s. The first two pictures in Ian Berry’s England 1975 published in the Arts Council’s British Image 2 of 1976, are of an epic leisure scene, reminiscent of Seurat, taken in Whitby and of a group of four shepherds at Hethpool in Northumberland. The Whitby scene appears to feature people in a dream – valedictory with respect to either the town or the nation itself. The shepherds in their turn have arranged themselves 3:1, maybe reflecting the charisma of the tall figure in the foreground. Perhaps Berry is reflecting on celebrity. Laurence Cutting’s picture of a winning jockey, taken at Ripon in 1977, also remarks on charisma, as having visible properties in relation to the talkative acolyte, an easily disregarded representative of the commonplace world.

Coda

Photography’s mission statement, from the 1940s through to the ‘70s, recommended that pictures should take account of society and culture: institutions, the stages of life and new topics such as celebrity and social dislocation (often reflected in the dispersed style of the new British documentarists of the 1970s). If the picture was nicely put together and had some metaphoric aspects which would give pause for thought it was justifiable and could take its place on the world stage, or at least as part of a national survey. At the same time there were challenges to this outlook. The ‘meteors’ of the 1950s and ‘60s had favoured appearances and fabric rather than the spiritual infrastructure; and in the ‘70s young British photographers experimented with compartmentalised (montage) documentary which proposed alienation as the norm.

Until the 1970s photographers had been able to assume that their relations with the public were mediated by a national press – by the Herald, Picture Post, and the Sunday supplements. This direct line to the public became unreliable and in the ‘70s the Arts Council tried to make good the relationship with its bursaries and British Image publications (1975-8). What could be more natural than that an increasingly homeless photography should find accommodation in the art world. Art was in the same business of reflecting and serving society as the press, but it was duty bound to respond rapidly to changes. At first (see British Image 1 and 2, from 1975-6) it was assumed that the old aesthetic with its social values was still operative, but by the end of the decade (see especially the Arts Council’s Three Perspectives on Photography, 1979 at the Hayward Gallery) publications reflected diversity: poetics, feminism and politics in 1979. The belief which had sustained photographers for over 20 years, that there was a unitary public sympathetic to a recognizable style in documentary, was no longer sustainable. There were photographers committed to the deciphering of Frederic Jameson’s prose and to the eradication of false consciousness, others affiliated to local amenity groups, and a few entranced by the look of thickets and rocks. There was no common ground, and no hope of a shared public.

It must have been exhilarating to be free, albeit in an increasingly unfathomable environment. The ‘meteors’ had photographed as if in a world where insights were off limits, where only appearances counted. The ‘meteors’, though, still had the idea of a common culture, even if they kept their distance. But from the 1980s onwards you were on your own in a society were there were communities, but no community as the term might have been understood in the 1930s. You were at liberty, as never before, to sift through the cultural wreckage; and suddenly all the formats became available, because there were no longer any regulations or even expectations.

It was impossible, in this postmodern set-up, to justify yourself along traditional lines. But if you cared to persist you qualified as an explorer investigating a poorly understood landscape. Perhaps the thicket photographers of the ‘70s and after weren’t far off the mark, metaphorically at least, with their probing of the dark zones. The outcome, during the 1980s and ‘90s, was more of a test than ever before. Previously there had been a consensus regarding subject matter and relevance in the broader context, but under the new rules of engagement anything might count. There were no longer any handy criteria that had been tested in action. Even if a photographer felt that a set of pictures had a special significance there would be no way of knowing for sure. They might be too close to a particular topic, in which case the sense of quest would be lost, or they might simply be too personal to mean anything at all. The knack was to get the judgement just right, although with no one to tell you one way or the other. Since the coming of instantaneity photographers have been alert to providence and to what it might or might not deliver; Cartier-Bresson’s decisive moments are providential. More was at risk, though, for the questing postmodernist who might reveal him or herself as contemptible.

It was a question, too, of catching the right moment, and of being in the right place. Bob Jardine’s The Promised Land, published by or at the Milton Keynes Exhibition Gallery in 1990, looks like a successful wager – one of the few in this demanding line of business. In 1990 he was probably still close enough to photography’s bygone social dimension, and as a ‘new town’ Milton Keynes still had modernist connotations. The book’s forty pictures implicate the town, still in a process of construction, with extracts from the photographer’s family life. He is an ironist, as you have to be in any postmodern context, but sometimes the irony is disturbed by startling real-life confessions. There are traces of New Topography, if you care to remember Baltz, Adams and the others, and echoes from elsewhere – just enough to keep the tradition in mind.

Perhaps The Promised Land was apposite in 1990. One of the things photography has been about increasingly from 1930 onwards is the unfolding of history and its moments. In 1938, for example, the mental landscape was well furnished with images of tanks and of dive-bombers, backed up by high-profile politicians. In 1955 (Family of Man) all the peoples of the world were on stage in their national costumes. Thereafter it became harder to envisage the historical moment, especially from a national point of view. In Jardine’s account of 1990 there remain traces of a national iconography, in the shape of motors, business parks and celebrity lookalikes at an event, but it is an elusive vision of the nation at that time. Jardine’s may in fact be the last viable attempt at a national statement in British photography.

[/ms-protect-content]

Published in Photoworks issue 8, 2007

Commissioned by Photoworks

For more about our Photoworks Annual, click here.