Lewis Bush examines the archive of Cafe Royal Books and its function in the current arena of photobooks.

Books and photographs go back a very long way, all the way back indeed to the latter’s invention. The introduction of the world to photography partly took place through the book, in publications like William Henry Fox Talbot’s Pencil of Nature, published in parts from 1844-46. Talbot, while an innovator in many respects, was hardly unique in allying these two mediums, nor was he even the earliest to do so. That distinction probably belongs to Anna Atkins and her 1843 volume Photographs of British Algae, a book which has remained comparably obscure perhaps because of the author’s gender as much as the apparently rather dry subject matter.

Through twists and turns, the book and the photograph have remained wedded ever since, spawning a strange lineage which reaches in to almost every arena of life and knowledge. The line of descent from Talbot and Atkins to the books of the present runs through publications as diametrically opposed as the state funded propaganda books of the early twentieth century, and the anarchic counter-cultural publications of the sixties and seventies. It runs through scientific compendiums of illustrations of illnesses and diseases, to those helpful books of photographs of common objects that travellers sometimes take abroad with them to help explain their needs to people with whom they do not share a language. And yet despite this long and well established pedigree, the idea of the ‘photobook’ as a distinctive and defined genre in itself, as opposed to a book which just happens to contain photographs, is a relatively new idea.

Over the last decade that idea has coalesced and photographers, overtaken by the exciting possibilities, have embraced the idea of the photobook in a way which has deeply affected the way photography is made, package, and shared. Today countless new books are published annually both by publishing imprints and by individual photographers, and new prizes, events and festivals concerned solely with the photo book appear constantly. Even generally conservative institutions are taking notice, with universities reconstituting their photography studies in response, and the appearance of exhibitions and even an entire museum dedicated to the subject.

The excitement that the photobook has fostered has had a range of consequences for photographers and publishers. Perhaps most often on the mind of someone conceiving a new book is the difficulty of producing work which stands out in what often feels like a heavily saturated market. The response is often either to make works of mounting conceptual complexity, veritable brain teasers in book form, or to produce publications of ever greater technical intricacy and material loveliness. Those books with an excess of intellectual complexity risk becoming irrelevant, accessible only to small audience, while those that emphasise material concerns often suffer a similar but opposite fate, accessible only to those with the material resources to pay for them.

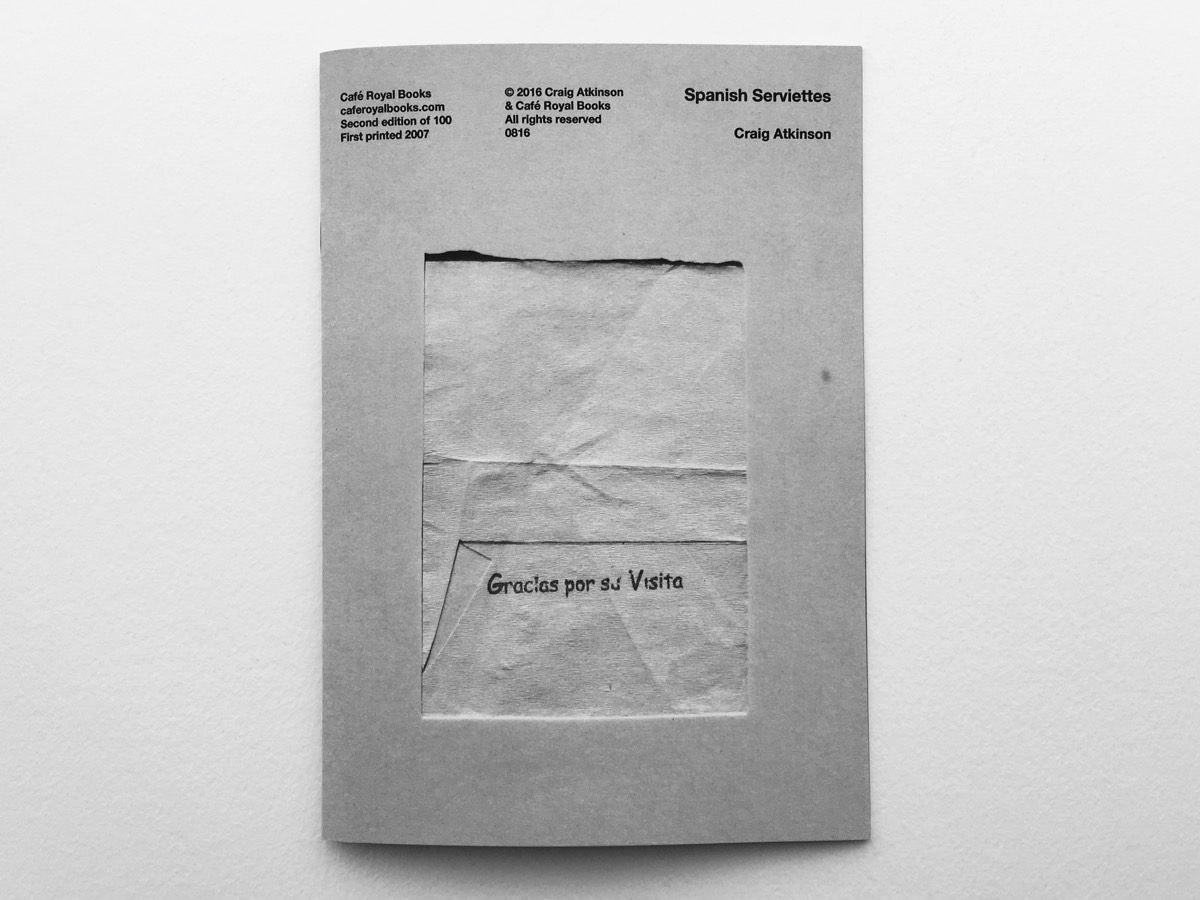

Alongside the opulent and the arcane though though there has always been a tradition of people producing books which prioritise accessible, relevant content over complexity and form. This tradition is one of a number into which one might place the activities of Craig Atkinson’s publishing imprint Café Royal Books. Over the last decade Atkinson has carved out a niche in the book making landscape, and indeed has carved out significant space on crowded book shop shelves, for small affordable books of great photography.

These volumes bear passing similarities to the fanzine or ‘zine, the small black and white publications often made on photocopiers or home printers. The zine has always been favoured by those outside the mainstream, it has long been a means of fulfilling needs which were neglected by traditional markets, or disapproved of by social conventions or laws. It has always been a platform of dissent both within the UK and without out. The form has some precedent in the flugschrift or ‘flying letters’ of the reformation, a genre of polemical, illustrated pamphlets that could be made and distributed in bulk by almost anyone, at a time when ideas and opinions about religious matters were no longer the exclusive preserve of the clergy, and when radical ideas flourished as a result. The first truly modern zines appeared in the early twentieth century, and responded to the burgeoning interest in science fiction, and the indifference of mainstream publishing to this growing genre.

Later bursts of interest in the genre coincided with periods of dramatic social change and uncertainty, like the counter-cultural zeitgeist of sixties America, and the punk rebellion of late seventies and early eighties Britain. These were periods of growing societal division and uncertainty about the future, and in that sense if in no other it seems thoroughly appropriate that Café Royal Books should reach the milestone of a decade of activity right now, in the midst of what some have described as the revival or resurrection of British neoliberalism.

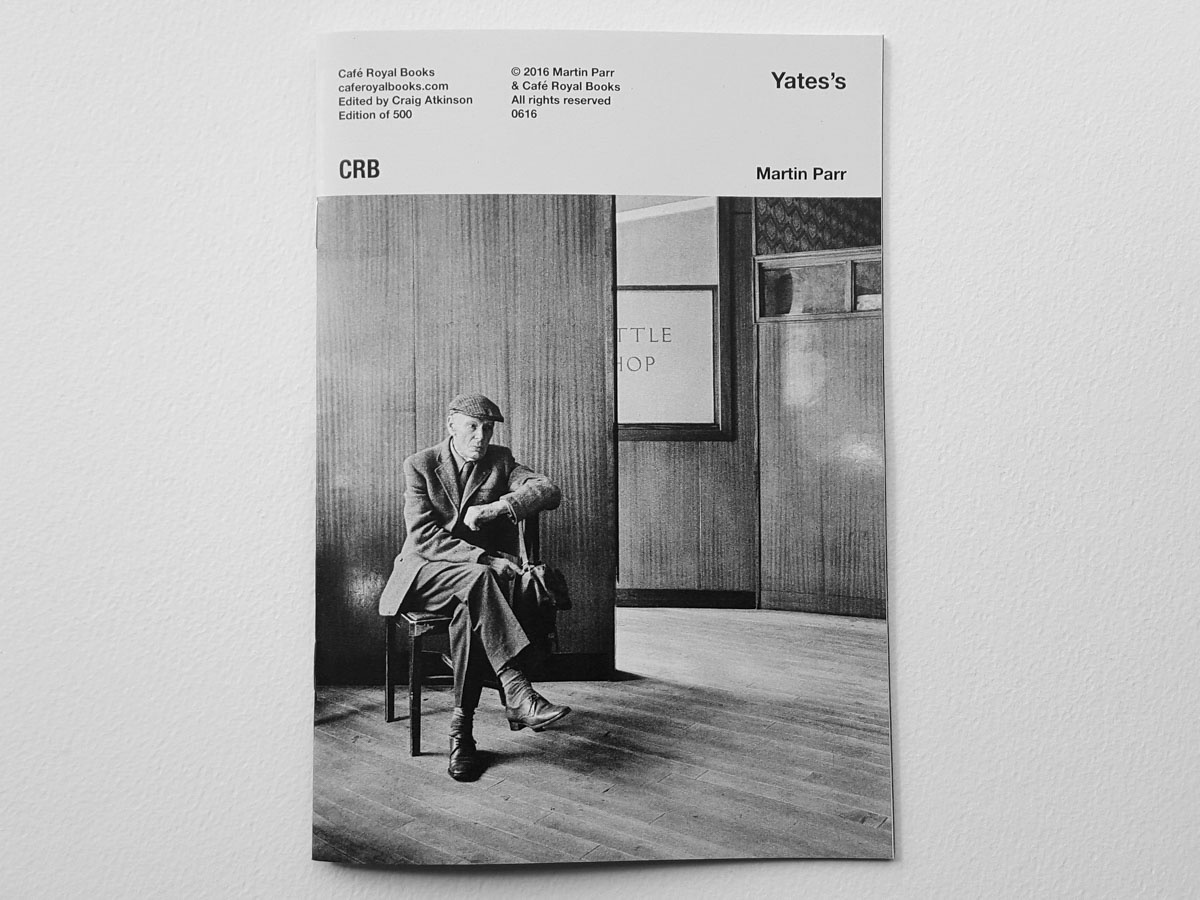

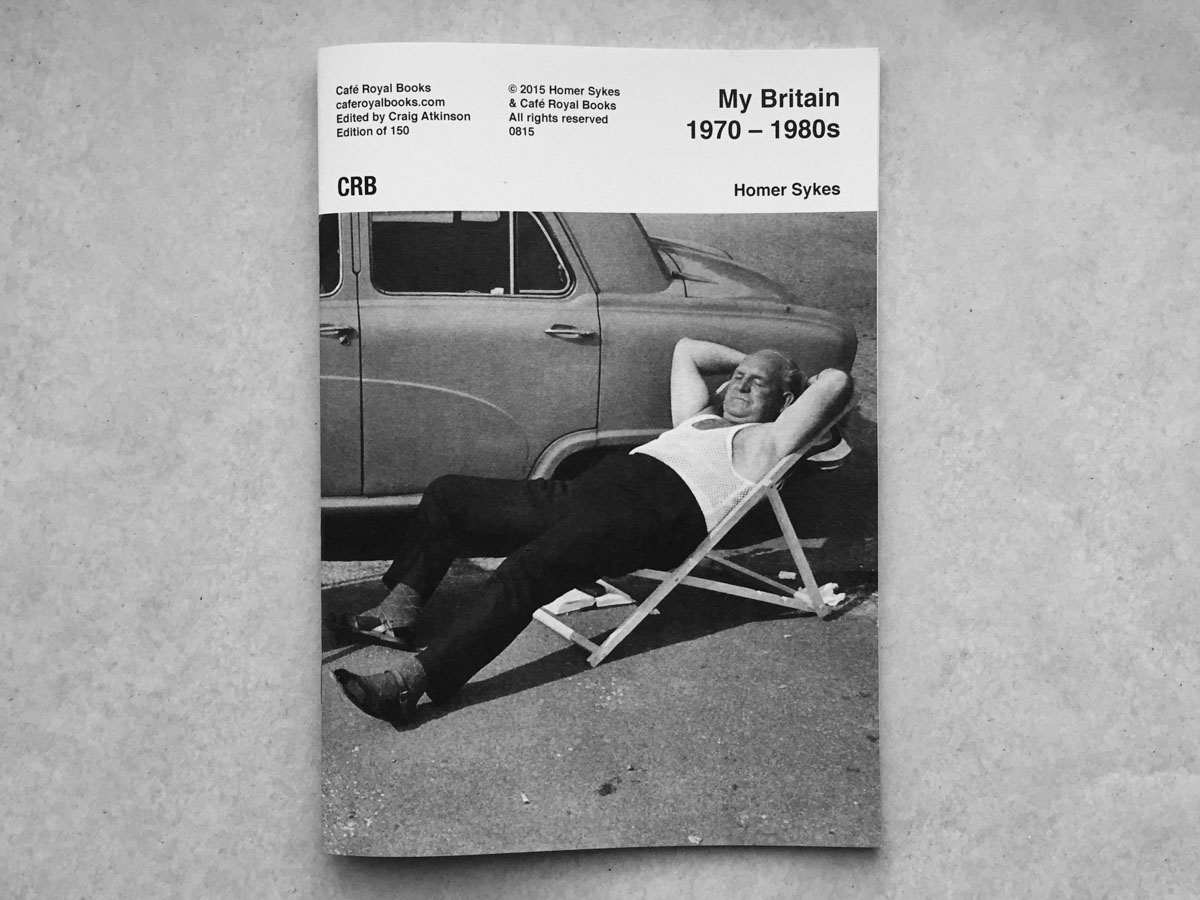

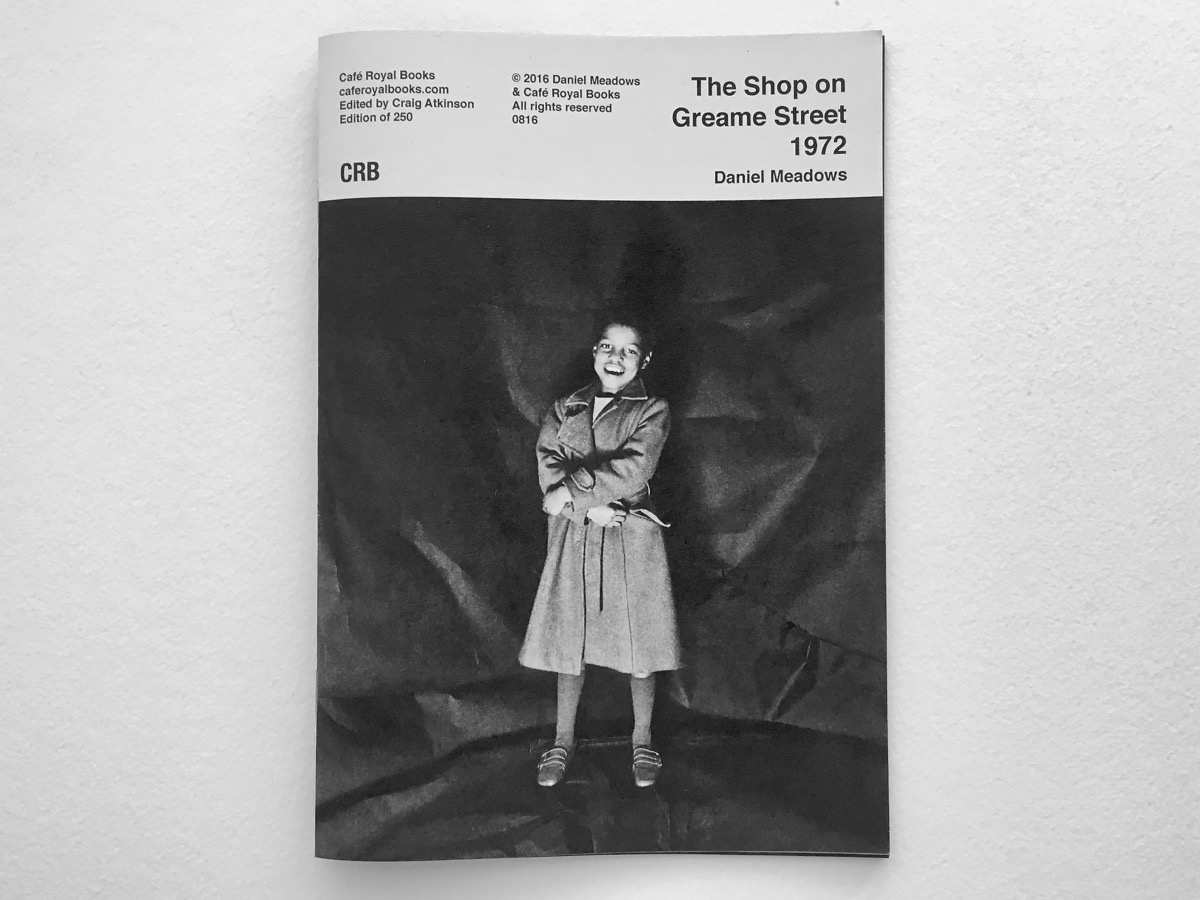

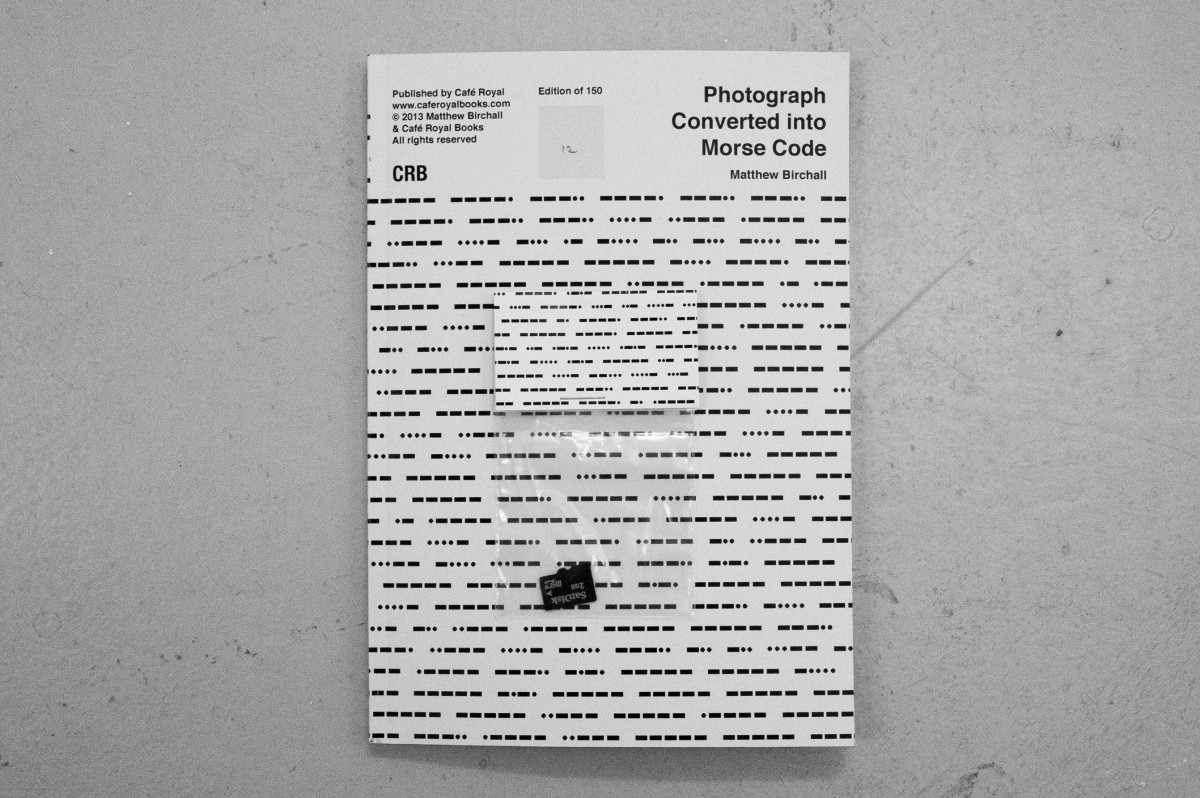

This timing is also apt given Café Royal’s loose remit, to explore change in the United Kingdom, something it does with a view to the past and the present, featuring works by well-known documentary photographers alongside new names. In Café Royal Book’s archive, works by canonical photographers like Daniel Meadows, Homer Sykes and Martin Parr brush shoulders with a new generation like J.A Mortram, Sophie Gerrard and Simon Roberts. These new photographers are staking out their own ground in a British social landscape which in some ways has changed enormously since that previous generation were producing their best known work, and which in other ways has changed very little. Alongside this relatively traditional documentary photography also jostles a small but growing number of photographers and artists experimenting with other forms, like Matthew Birchall’s book of a photograph rendered as Morse code.

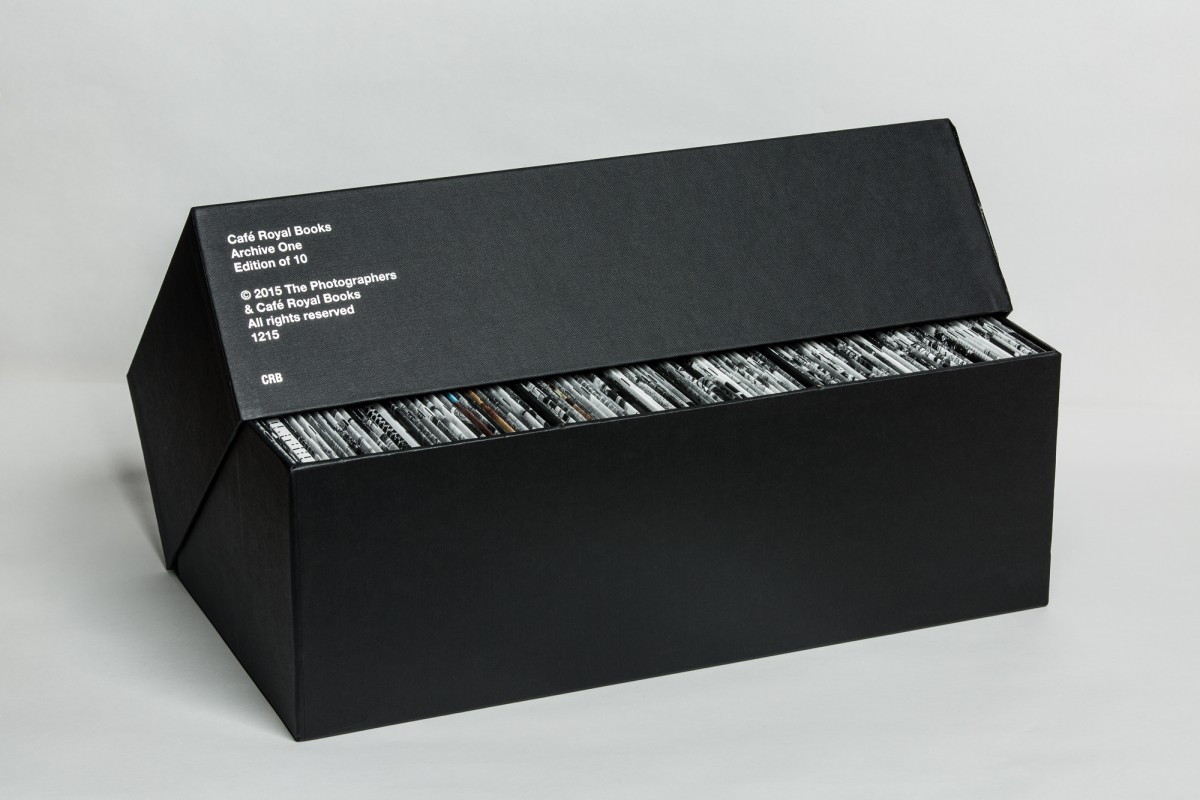

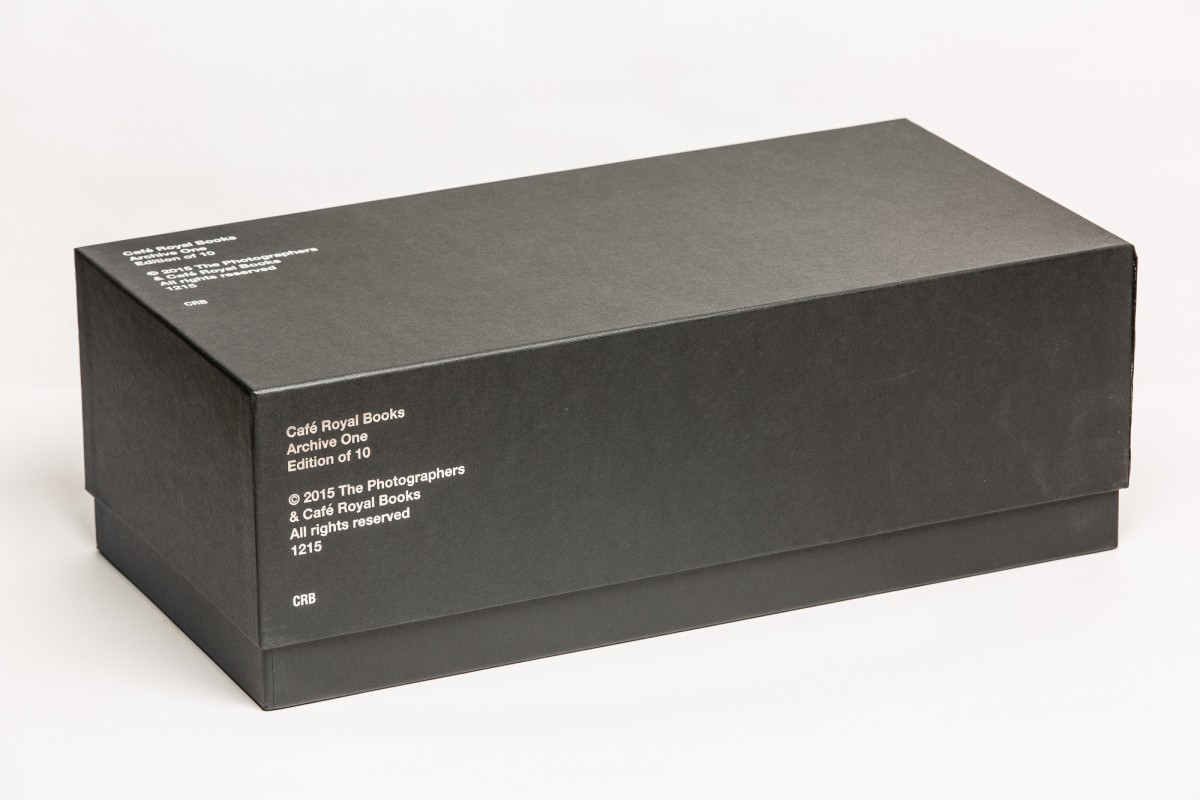

Café Royal Books is nothing if not a broad church, and in the process of combining these disparate works the imprint’s back catalogue is becoming a remarkable and eclectic archive of Britain over the last thirty years or more. To be sure it is not an archive in a traditional sense of a centralised collection, but it is an archive none the less, bound together by its format and idea if not by a single shared geographic location. In some ways this seems thoroughly modern, in the age of distributed storage and increasingly abstract information. It seems a powerful idea that in buying into Café Royal Books your own shelves are becoming an extension of that same hugely distributed archive. It is an archive of British social history, of changing clothes, architecture and environments, with an emphasis on the small details which photography is so good at remembering, but which conventional histories so often forget. The styling of an eighties supermarket for example, or the now perhaps almost forgotten craft of how one slaughters a pig by hand, away from the abattoirs of industrial farming.

Equally though Café Royal Books is almost just as easily viewed as an anarchic archive of British social photography, picking up on projects and small sets of images that might easily have been forgotten, languishing neglected in the corners of a photographer’s archive before perhaps being swept into the dustbin of media history. Cafe Royal Books has become a new home for works which sometimes deserved but did not get an airing at the time that they were first made, which in the realm of documentary photography was certainly many. In this sense, as well as being an archive itself, Café Royal Books is an archive made of archives, a series of small tasters of many photographers’ larger bodies of work.

Atkinson is the archivist of this project, defining like an archivist what enters the collection and how new additions augment the existing whole. So these volumes occupy a strange place between the mass produced zine and limited edition photobook, between fragile and ephemeral objects and part of an ever more massive, distributed and enduring whole. For all that it borrows from other traditions, Café Royal Books remarkably manages to elude comparison to almost anything else.

Part of the reason for the renewed concentration in the photobook was the huge appeal of a medium which appeared to short circuit so many of the interests and priorities of traditional outlets like galleries and magazines. Books seemed to again give photographers a space where they could speak without restraint or intervention. In some respects the photobook has now acquired it’s own vested interests, and its own limitations. But there remains a vanguard of small and self-publishers though who shine the light for a truly independent publishing, which has more in common with Anna Atkins and her first diminutively radical book.

For more from our Ideas Series, click here.

For more on Cafe Royal Books, click here.