From issue: #19 Image Flow

Why publish your images in a book? Photobooks are engrained in contemporary photography, but they’re expensive to make and distribute, and the internet and social media provide easier ways to show work. So why bother? What can a photobook do that other means can’t?

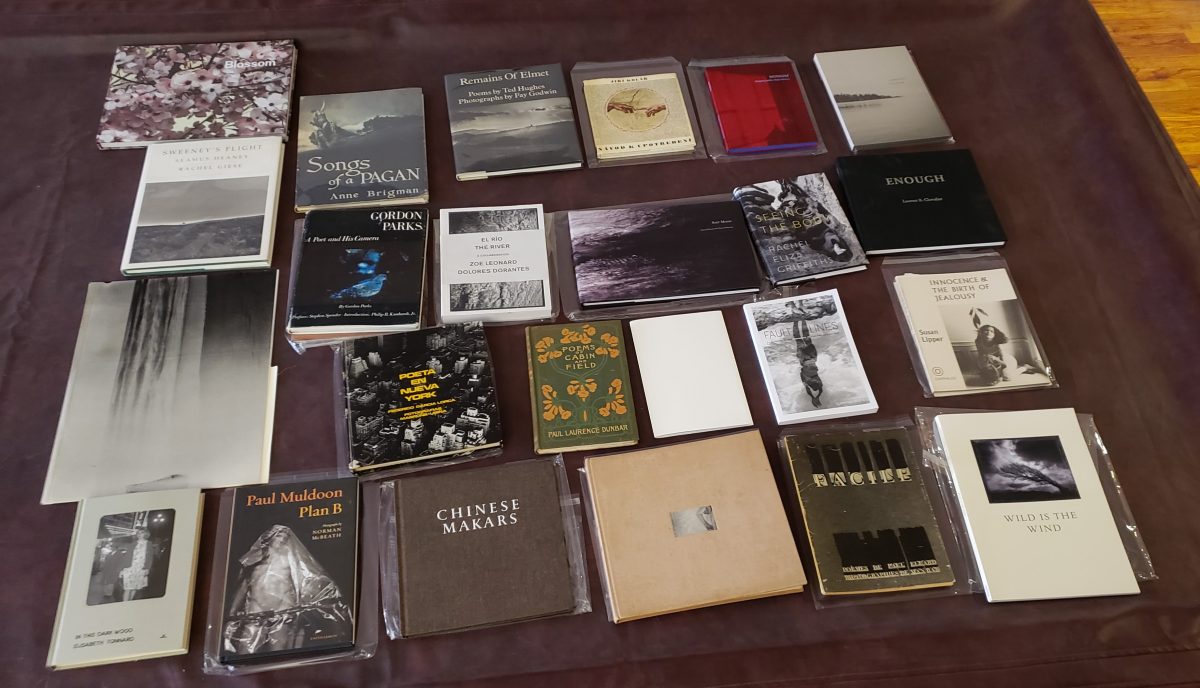

These are some of the questions that exercise David Solo, who has built up a collection of some 8,000 artists’ books over the past 30 years, with a special focus on photobooks. Until recently, Solo was on the board of the Aperture Foundation, and he’s a trustee of the Kraszna-Krausz Book Awards. Solo is grants director at the non-profit organisation 10X10 Photobooks, which has spearheaded projects such as the publication What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999. He helped to organise The Photobook Sessions conference in London in 2021, with the Kraszna-Krausz Foundation and Camberwell College of Arts, and also co-organises the Contemporary Artists’ Book Conference at New York’s Printed Matter book fair, the most recent iteration of which was in Autumn 2022.

In 2021, Solo published an essay in Aperture’s The PhotoBook Review urging critics to ask wider and deeper questions about photobooks. Current photobook coverage offers a wealth of information about the images in publications, he argued, but they are ‘leaving open the question of how, or if, the work functions differently as a book’. ‘This is not to say that all writing must do all these things,’ he continued, ‘But I do argue that a richer diversity of writing needs to be encouraged and supported so it can be made available to audiences who are, or who might be, interested. Without robust critical frameworks and debate – and platforms to support and distribute such writing – the audience of the photobook cannot mature or expand.’

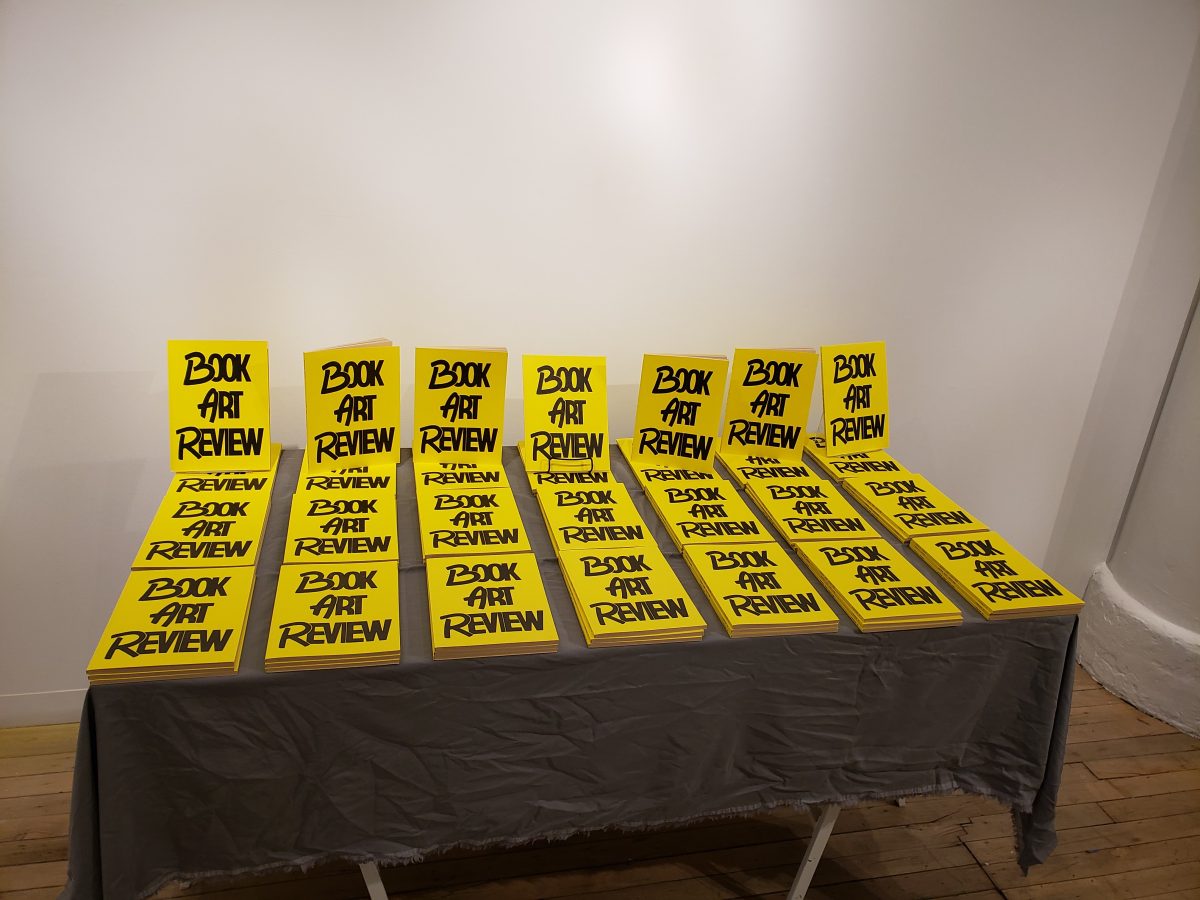

These thoughts inform Book Art Review, a new biannual publication which Solo co-founded with the Center for Book Arts in 2020, and which published its first issue in 2022. The Book Art Review looks at artists’ publications and asks why they’re books, what this format adds, and how it does so – and very much includes photobooks in its remit. ‘I’ve been on probably more panels or conversations or bar chats than I care to think about on the artists’ book versus photobook definition kind of question,’ Solo laughs. ‘In my view, a photobook, as opposed to a sort of catalogue of photographs, is an artists’ book that happens to use photographs, whether ones that the artist made, or selected, or otherwise.

‘In artists’ or art books, the artist – or photographer, or whoever – is viewing the book as a work in and of itself, as an expression of their idea,’ he continues. ‘Sometimes it makes sense to look historically at photobooks as discrete media, and of course there are some practical issues: reproducing photographs or digital images – the actual mechanics of production – are easier [with photographs] than if you’re talking about drawings or paintings or sculptures or other visual imagery. But I think there’s more similarity than difference around how to use the book form as a platform. Often it’s helpful to start with that broader perspective.’

As Solo points out, some iconic photobooks were made by people primarily known as artists, and thinking of photobooks in terms of a wider history of artists’ books, and a wider cultural, social and political history, opens up new depths and new audiences. At the same time, Solo appreciates the particular history of photobook publishing. Learning photographic printing as a child, he has a long-standing appreciation for the medium and even studied electrical engineering with strobe innovator Doc Edgerton at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (though this was by coincidence rather than by design).

Photography, as Solo points out, is a singularly malleable medium. Used by amateurs, governments, advertisers and journalists, as well as artists and many others, it’s also spread widely online – so much so that researchers such as Andrew Dewdney argue that images are now ‘networked’. For Solo, this malleability makes the photobook all the more vital. Images can read very differently in different contexts, particularly if they’re given alternative captions and crops, he points out. By creating a photobook, image-makers can exert more influence over how their work is understood.

‘The book is a more persistent, more expansive, almost more fixed context through which to express a set of ideas,’ Solo says. ‘Whether someone who looks at that in thirty years’ time thinks about it the same way we do now is another challenge. But there’s more context for that hypothetical future viewer to draw on, compared to an image that is standing by itself. It’s an added layer that the maker or makers get to put around their work.’

On a personal level, Solo has long been interested in the connections between images in photobooks, as well as the interrelationship between image and text. For him, the key questions moving forward are how photobooks can evolve to include more makers and readers and to become more environmentally sound. ‘We need a broader discussion about the sustainability of photobook production, and accessibility for broader segments of the population,’ he says.

‘The economics of publishing in the artists’ book world has always been problematic, and most of the photobooks you see are still coming from Europe, North America, and Asia. We still have to think about the mechanics of book production and circulation. Maybe sometimes there are opportunities for distributed production, for example, in which instead of making little books in one place and shipping them around the world, you produce the book locally in smaller print runs in several places.’