An insight into the world of documentary photography for female photographers examines works from Chloe Dewe Mathews, Bieke Depoorter, Orande Mensink-Nouws and Marilene Ribeiro

New Wave

Some ten years back, I had the feeling that much documentary photography was losing something of its edge and that photographers were no longer as interested in this mode of production as a way to talk about people and place. Perhaps it was the fading magazine world that made this happen, the lack of spaces to exhibit work or the ubiquity of the camera in the modern world. Lately, I have noticed many more women taking up documentary and although a considerable number of them convert their practice to a more conceptual fine art practice either due to their education or simply through discovering that they really aren’t a documentary maker, some strong characters are staying with the genre. And they are exploring a wide range of very new approaches to documentary practice.

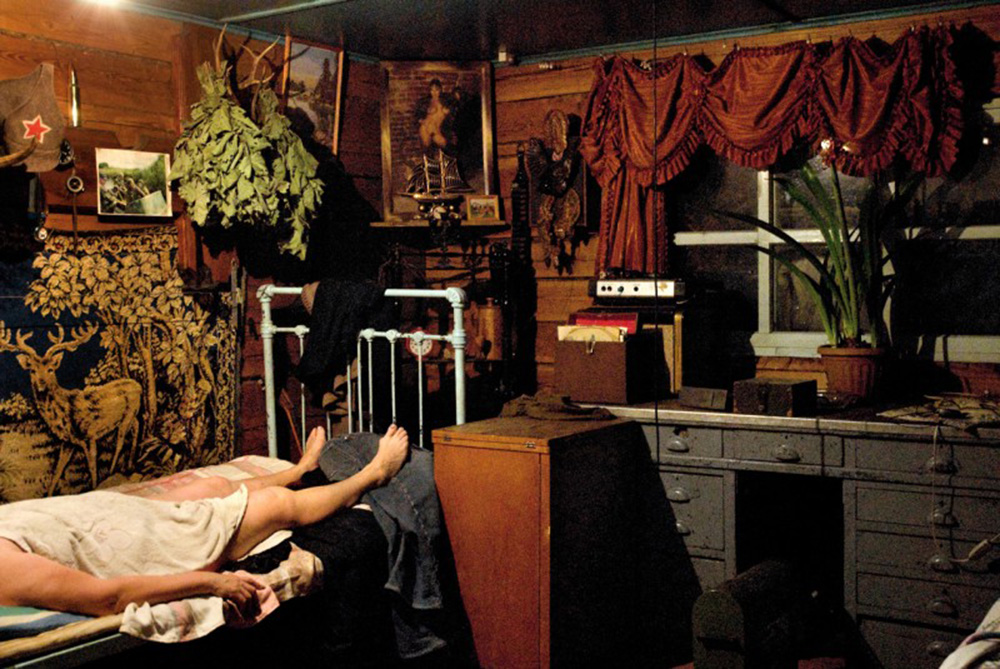

Bieke Depoorter has taken an interesting and arguably dangerous approach to documentary photography. For her project Ou Menya (With Me) she travelled through Russia staying with her subjects for one night (each subject) armed with little other than her camera, a sleeping bag and a translated note asking to spend the night staying in a stranger’s home. Without knowing any Russian she has managed to insert herself into many strangers lives, even though her stay in each home was brief. As someone travelling alone in a foreign land anything could have happened, but this vulnerability helped to break down the barriers to intimacy. Her photographs connect the viewer with the realities of life in a part of the world that is very far removed from the exhibition spaces in which the images are shown. Depoorter’s work brings an unusual view to the mundanity of ordinary life. The language barrier proved not to be an obstruction to the communication and cooperation of her subjects. As she says “You create a very special atmosphere when you live with someone but do not speak the same language”[1].

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

Orande Mensink-Nouws is a Dutch photographer living in the UK. Her project Haven questions the nature of home, what it is, how it comes about and whether you can bring it with you. It focuses on an expatriate community that she has been a part of and followed for three years. Being a member of the community she was documenting gave her a rare perspective and involvement in the work she produced. These expat women, that Mensink-Nouws photographed, are used to travelling, frequently following their husbands wherever their careers took them. Through the photographs we see that they appear to spend a large part of their free time socialising. Countless meetings, events and outings are attended, all very wholesome events where nothing serious goes wrong. The images are beautifully composed in a way that makes each happening appear like an oddly choreographed dance, the balance threatening to edge out at any moment but never actually tipping. What becomes apparent is the powerful use of repetition. Why are these women spending all of their time together? Why aren’t they wrapped up in work and home life in a way that is so familiar to the rest of us? Orande discovered for herself that in this kind of lifestyle home is not contained inside bricks and mortar but is an ever-evolving dream that is constantly chased. These colourful images echo early Tina Barney family images albeit with a different class of subject. There is a yearning for company threading its way through the series and an unspoken desire to do what is expected.

Chloe Dewe Mathews’ project Shot at Dawn is a series of photographs made in locations where First World War soldiers were shot at dawn for their so-called cowardice. The photographs attempt to recreate the setting as accurately as is possible without staging a full re-enactment. They were taken as close to the location, time and season in which their significance was created. Mathews’ work is a more conceptual approach to documentary photography than the other photographers that I am discussing. A curious mix of conceptual art and documentary photography popularised in the UK and US photo art worlds over the last fifteen years (or so). Each image has been thoroughly researched, planned and contemplated before executing her vision; in fact research was the most extensive part of the project. Mathews’ work echoes the complex and compelling work of the eleven women photographers seen in the 1994 exhibition Warworks[2]. curated by Val Williams (V&A, Canadian Museum of Photography and Rotterdam Photo Biennale). It is unusual in that rather than documenting people or lives, Mathew’s work uses landscape photography (without a living subject) to comment on the tragic effects of war. The work comprises a series of very quiet and sombre pictures emphasised through the dark bluish quality of the images. A memorial to the lives that were lost, not through documenting the hectic horrors of combat but through carefully observing the locations where death was metred out numerous times through a methodical procedure, bizarrely conducted in the name of morale.

Soldat Ernest François Macken

Soldat Benoît Manillier

Soldat Francisque Pitiot

Soldat Claudius Urbain

Soldat Francisque Jean Aimé Ducarre

06:30 / 7.9.1914

Soldat Jules Berger

Soldat Gilbert Gathier

Soldat Fernand Louis Inclair

07:45 / 12.9.1914

Vanémont, Vosges, Lorraine,

Shot At Dawn, Chloe Dewe Mathews

Soldat Ali ben Ahmed ben Frej ben Khelil

Soldat Hassen ben Ali ben Guerra el Amolani

Soldat Mohammed Ould Mohammed ben Ahmed

17:00 / 15.12.1914

Verbranden-Molen, West-Vlaanderen, Shot At Dawn, Chloe Dewe Mathews

07:22 / 21.12.1915

Private John Docherty

07:12 / 15.02.1916

Private John Jones

Time unknown / 24.2.1916

Private Arthur Dale

Time unknown / 3.3.1916

Private C. Lewis

Time unknown / 11.3.1916

Private Anthony O’Neill

Time unknown / 30.4.1916

Private John William Hasemore

04:25 / 12.5.1916

Private J. Thomas

Time unknown / 20.5.1916

Private William Henry Burrell

Time unknown / 22.5.1916

Private Edward A. Card

Time unknown / 22.9.1916

Private C. Welsh

Time unknown / 6.3.1918

Abattoir, Mazingarbe, Nord – Pas-de-Calais

Shot At Dawn, Chloe Dewe Mathews

Marilene Ribeiro’s project Dead Water focuses on communities that have been forcibly relocated in order to construct the Sobradinho Dam, Brazil (the project is on going and she will be photographing communities at three other dam locations in Brazil). Ribeiro’s work is made in collaboration with her subjects and this has been a vital part of the project. The process begins with an interview with the subject who then chooses a location and an object that hold significance both to the subject and to the narrative (of what has happened to the community through the forced movement). An initial photograph was taken and then discussed. The session was then largely directed by the subject until an image was created (and selected by both photographer and subject) that reflected the mood, memories and consequences of their relocation. Although not all of Ribeiro’s subjects were initially interested in taking part in her project they were encouraged by the experiences of their friends and neighbours. Her collaborative approach has assisted the community to express their thoughts, feelings and stories in a way that is deeply personal to them. Ribeiro’s project demonstrates a highly innovative storytelling practice that lends power to its subjects and invests in people’s histories and futures in a different way to most documentary practices. She intends to take the final work back to exhibit or project it where it was originally made as well as using the work to inform the wider world of the pressing issues facing these communities.

The world of documentary photography can be a tough place to produce new and existing work. It seems that it has, in the past, been especially difficult for women photographers. Why exactly this has happened is not entirely clear and it would be interesting if some proper research was commissioned to investigate the situation. Often women who start work in a documentary field seem to leave the business to concentrate on developing work for an art market place. Depoorter, Mensink-Nouws, Mathews and Ribeiro have all made an impact of their own, they represent a new generation of documentary photographers impatient to bring innovation into the practice, I look forward to seeing what happens next.

References

1. http://bintphotobooks.blogspot.com/2011/10/couchsurfing-in-siberia-ou-menya-bieke.html

2. Warworks by Val Williams, Virago Press 1994

Essay ©AnnaFox/Felix Fox 2016

Chloe Dewe Mathews: Shot at Dawn is commissioned by the Ruskin School of Art at the University of Oxford as part of 14–18 NOW, WW1 Centenary Art Commissions

For more of Anna’s work, click here.

For other Ideas Series articles, click here.

[/ms-protect-content]