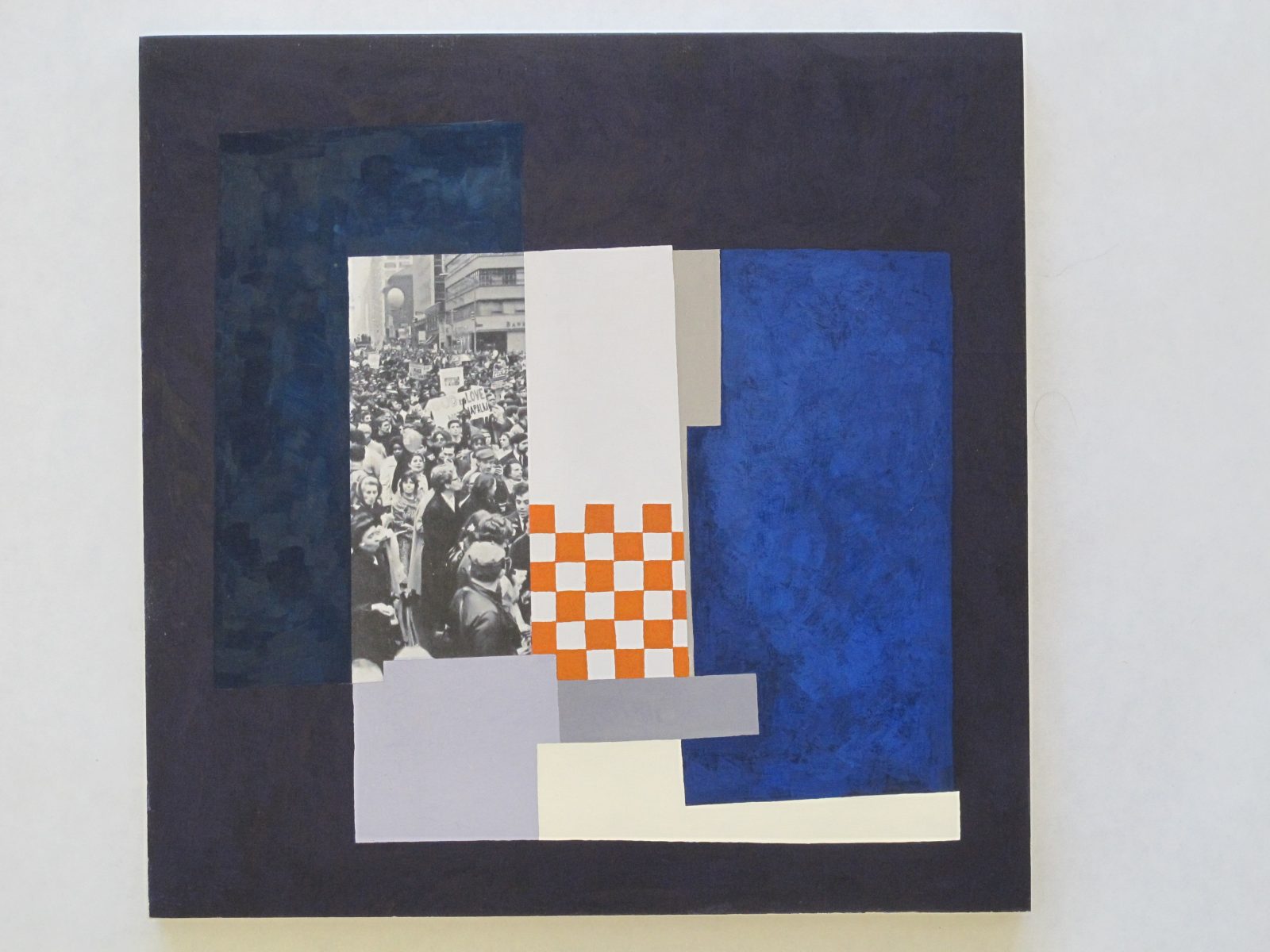

Two blues: cobalt and cave. One white, tinged cream. Three grays: graphite, fog, cement. A grid checkered soft red-orange and white. Nightshade purple.

Framing all these, attic black, full of something stored. And a black-and-white photograph, with or without a fragmented caption. This fixed set—nine colours plus one photograph—reshuffles in shape across the six small tempera paintings that comprise Doug Ashford’s series Six Moments in 1967 (2008-2011). With a colour omitted here and there, each work tests out the allotted palette in a varying repertoire of abstract shapes, which reflect but do not conform to the square dimensions of the wood panel support: cropped planes; squares askew; swatches cut on a bias; cleated planks; shims and sills; irregular brackets. Each photograph acts as a heuristic for the painted configurations it provokes. Culled from Ashford’s long-running collection of clippings and tear sheets, the photographs document instances of collective, democratic mobilisation in the anti-war and Civil Rights movements in 1967: a protest in Detroit, the October antiwar march at the Pentagon, another peace march elsewhere, and a demonstration in Vietnam.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

Seemingly incommensurable modes of representation collide: the indexical (photographed events of social upheaval) and the abstract (the elimination of any referent); the public and mass-mediated (photojournalism) and the private and handmade (tempera’s antiquated studio-based process). If geometric abstraction helps describe the oscillation of figure-ground relations (Ashford has cited the painter Myron Stout), it cannot see us through to the historical content of the title and photographs, nor the animating perceptual depth the latter cleave. The close weave of archival photograph and abstract painted surface strays far from the winking cynicism often accorded to Pop (Warhol’s monochrome silkscreens, especially Race Riot, may lurk), or to strategies of appropriation predominant in the 1980s, the decade in which Ashford’s work developed in the context of the New York collective Group Material. Like the group exhibitions designed and organised by the collective in the 1980s, Six Moments helps us rethink appropriation in terms of desire: the desire to forge connections with history and with the idea of representation (in democracy and communication alike), rather than merely belabor their crisis or end.

At a time when “social practice” predominates in contemporary art (a way of working that Group Material helped define thirty years ago), Doug Ashford asks, with Six Moments and other recent paintings: What are the possibilities and possible risks of abstraction applied to the sphere of politics? Can there be an ethical abstraction? The basic structure of abstraction seems primed to refuse. Its etymology: “to withdraw’ or “turn aside”. Its historical conditions: a currency of power that, in neoliberal capitalism, recruits labour, exchange, and value under its sign, and strips away the evidence. Its function in spectacular culture: where images become digitally interchangeable, and weakened in their force by their very surfeit. Six Moments registers this latter form of abstraction quite precisely. Cut loose from context, its four photographs (the first two paintings present different segments of the same image; as do the fourth and sixth) have been scanned by the artist and passed through a digital filter to homogenise their original ben-day patterns. Printed on a plotter, most appear without captions, or only fragments, and these—small, grainy, and cropped—cannot be decoded with much certainty. Formal interventions of coloured blocks and shapes widen the photographs’ separation from historical specificity. Framed within the devotional associations of tempera on board, the photographs point not only to an indexical real; they also seem focused on an ideal.

At once abstract and evidentiary, Ashford’s painted forms produce a similar tension. They refuse a referent, and remain abstract in that sense. But they insist on the brute materiality of the medium itself, a hand-mixed solution of egg yolk, pigment, water, and Damar varnish. The term “surface” is inadequate to describe the vividly haptic, dimensional fields that result, since, depending on the viscosity of the solution, pigment floats suspended, transparent to previous layers. In the absence of illusionism, an actual depth accrues: a build up of pigment, matt and dense, luminous but without gloss. In larger areas of colour, pigment appears to mass and gather, as if to theorise the conditions of collective assembly mirrored in the crowds of demonstrators pictured photographically.

Six Moments’ non-illusionistic painterly quality recalls Suprematist and Constructivist precedents in several ways: the turn to abstract imagination in the context of political thought; the square that is not quite a square, set into motion by the faintest diagonal. These affinities not withstanding, the affect of Six Moments lies far afield. These paintings want to invite a sense-experience of colour and shape (this purple square, that blue bracket) that might also trigger something like a sensory recognition of the event documented in the photograph (that day, that crowd, that protest at the Pentagon). They seek cathexis (Ashford’s term is ‘empathy’ ) with their subject as an ‘abstract possible’. In this aspiration, composition serves a key function. Suprematism’s postwar inheritors (Ellsworth Kelly, for instance, or Minimalist sculpture) turned to the grid, the square, and the serial form as structures of anti-authorial withdrawal. In Six Moments, compositional permutations from one painting to the next reflect a processual effort to find a fit, to puzzle something out by trial and error, as though in doing so a connection to history, and to political desire in the present, might be consummated.

The scale of Ashford’s paintings make no grandiose claims, and their puzzles refuse a snug fit. Edges stutter out of alignment; gaps are filled, provisionally; corners snag, not smooth: and so the need, or desire, to try again, without any conclusive solution posed. This is how nostalgia is kept at bay. Six times we are asked to work through our relationship both to a particular history of struggle (the events of 1967 indexed by the photographs) and to an ideal of collective agency (the abstract ideal signaled in these same photographs). If the connections forged to both are inconstant and idiosyncratic (even the very same photograph may produce different results) the desire that motivates this archival impulse is never in doubt.

[/ms-protect-content]

Published in Photoworks Issue 18, 2012, edited by Gordon MacDonald.

Commissioned by Photoworks

Buy Photoworks Issue 18