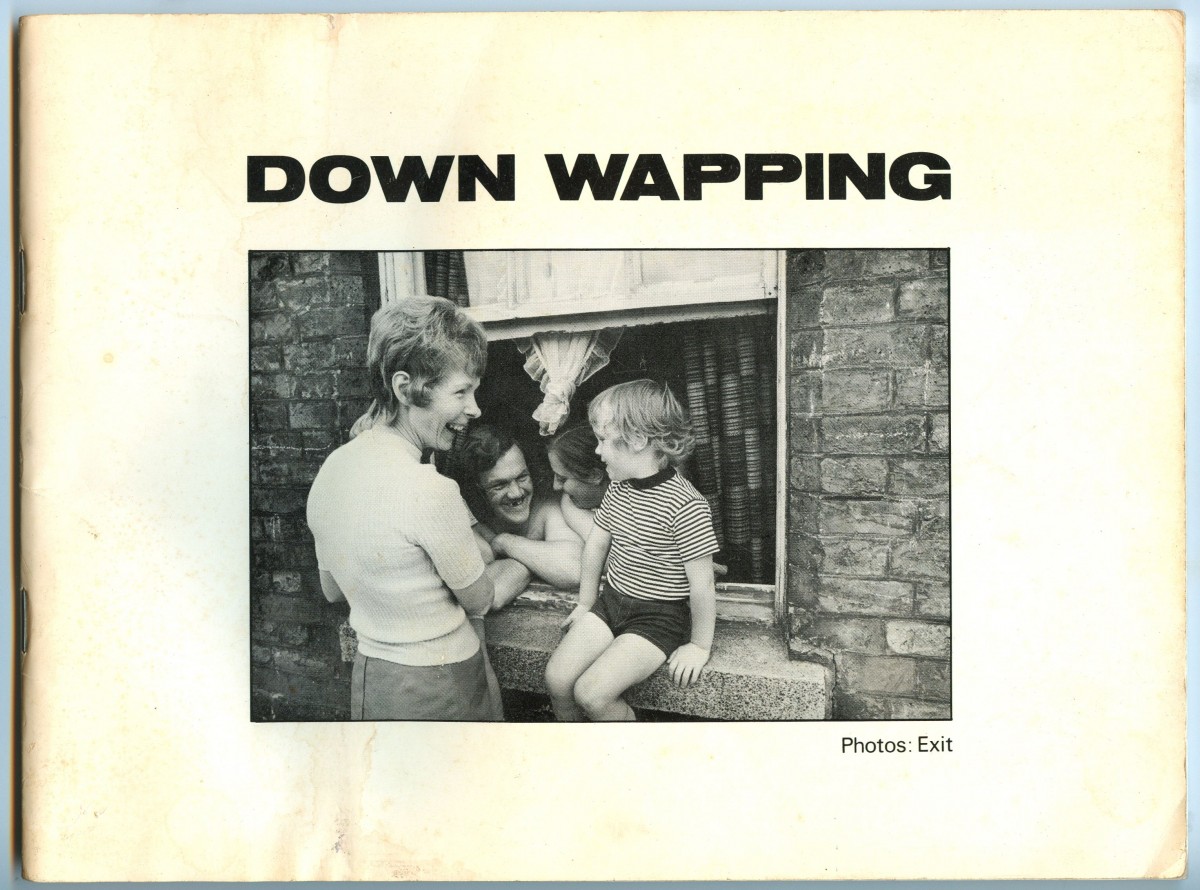

Exit had been in existence some time before I joined. They had published Down Wapping, a small booklet in 1973 about the working class community in Wapping, East London and it contained the work of four photographers, Nicholas Battye, Diane Olson, Alex Slotzkin and Paul Trevor.

My contact with Exit began when I saw a small notice pinned up in The Photographers’ Gallery in London to the effect: Photographer interested in social issues in UK call Paul, and a phone number. I called the number up a few days later and arranged to meet up with Paul, Nick and Diane, the current members of Exit in Paul’s flat off Brick Lane. The flat was soon the de facto office for Exit.

Paul was clearly the organizer and explained they wanted to go beyond Down Wapping and look at the larger issue of inner-city poverty across Britain. It was a subject that interested me, they were ambitious and serious and had shown, with Down Wapping, that they finished what they started. There was one major problem, they had no money, but it seemed appropriate that we should live on the margins of poverty while attempting to document it. I agreed to join them.

Various changes took place inside Exit after that. Alex Slotzkin had already left and then Diane left. For a while we worked with the Jazz writer and photographer Val Wilmer, but that did not work and soon we were down to the core of Nick, Paul and myself, and it remained that way. We had some support from the Gulbenkian Foundation who had been impressed by Down Wapping and had proposed a project on inner cities. However we had to apply to them for grants to fund the work and we got some money, though it was a fraction of what we needed as we never expected to be working on it for as long as we eventually did, but it was essential to get us properly started.

The political/theoretical position we shared was that inner-city poverty was endemic and for an advanced industrial society, intolerable; that poverty, injustice and discrimination was leading to serious social disorder which had the potential to develop to the level currently experienced in Northern Ireland. We all agreed that it was important to make an oral record, from interviews, of people’s experiences of living in poverty. As well as making a photographic record. Ronald Blythe’s book Akenfield and Evans and Agee’s, Let us now Praise Famous Men were two of the many influences in that direction. As a collective we decided not to credit our photographs in the book we planned, thinking that was a collective sort of thing to do.

Paul, the son of a taxi driver, was enthusiastic and energetic and at times extremely irritating, but he was the driving force behind Exit. He took care of the accounts and wrote the introduction. Nick was a quiet Australian aesthete. He was a private person, but Paul and he had a friendship while for me he remained a colleague. Unlike Paul and myself he did not think of himself as a photographer. He was on a spiritual quest, studying under Teachers and reading Gurdjieff and Ouspensky. I was the only one who worked as a freelance photographer, Paul did some teaching and Nick wrote and studied. Photography was only a passing phase for him.

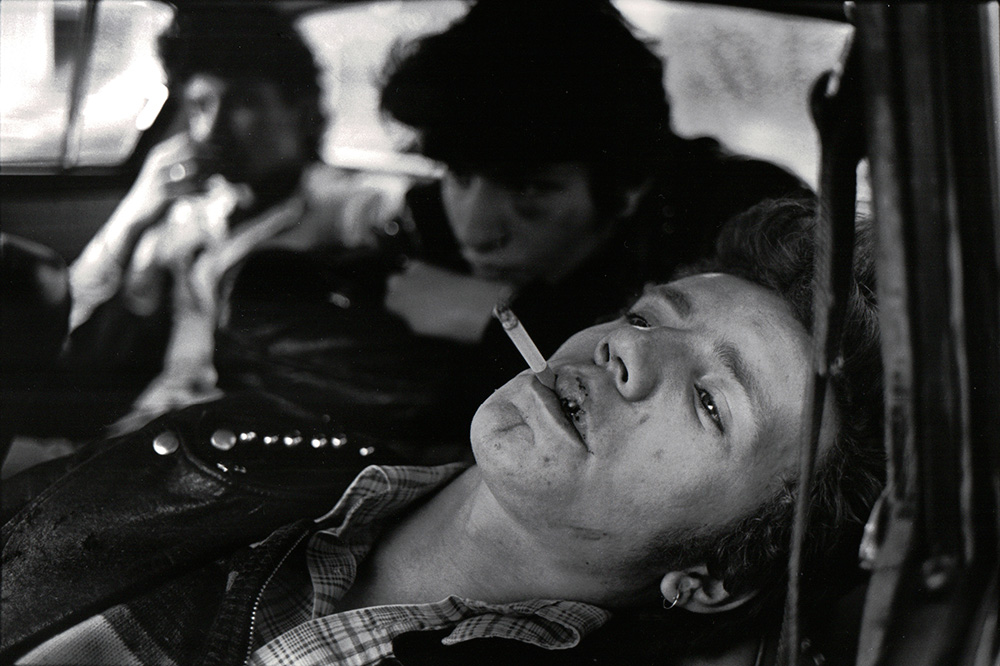

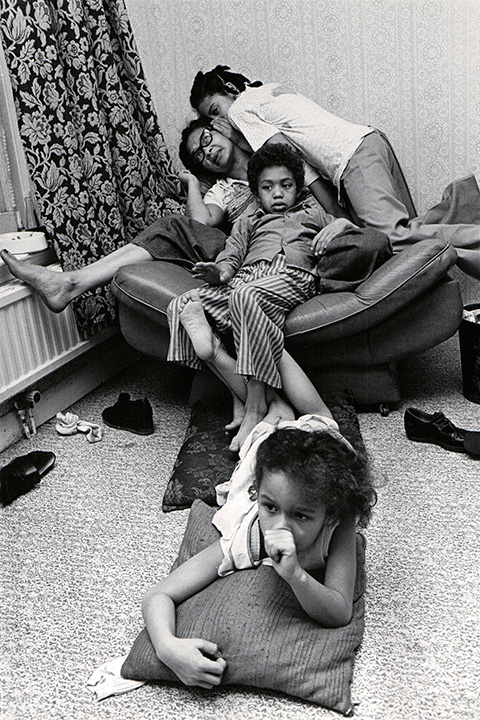

We agreed to divide the UK up between us. We all did some work in London as we all lived there, and we all did some work in Glasgow, but most of Paul’s time was spent in Liverpool, Nick’s in Birmingham and mine in Newcastle, Middlesbrough and Belfast. We made contact with community organizations in search of contacts, we also did a lot of walking around deprived districts, talking to people in the street, knocking on doors. There was a different relationship that people had to photography then, compared to now. People welcomed us into their homes, litres of tea were drunk. We slept on floors, friend’s sofas, cheap B&Bs.

We all shot in black and white often loaded our own film into cassettes to save money, and processed the films at home. We also transcribed our interviews. We all looked at each other’s work, discussing, criticising and choosing images, which we printed as 6×4 inch proofs which were pinned up all over Paul’s flat as part of the editing process. The transcribed interviews were cut and pasted together as a result of discussion. We planned to give equal space to the interviews in any book we made, using them as compliments and additions to the photographs, not captions, or explanations for the photographs.

The photographs were sequenced from community through frustration into anger in 4 chapters we called Growth, Promise, Welfare and Reaction. The format of the book was simple, one photograph on the right side of the page and interview text on the left. Because of other commitments, lack of money, inexperience, it took a long time to get the book finished and it took a long time to get the book published, but eventually the Open University press published it in 1982. The project had started in 1975! Side Gallery in Newcastle printed the exhibition and toured it around the country and one set of exhibition prints were kept by us. The Gulbenkian were given a set of 300 representative prints for their records which are now in the care of Birmingham City Library. The archive is held by the London School of Economics.

Exit members went their separate ways but left behind what I believe will eventually be recognised as a landmark project in the history of British photography and an important document on British social history.