Taken from our latest Photoworks Annual Issue 23 titled 'Self-styled', Ben Fountain looks at the works of Leah Gordon in relation to our Biennial themes.

They don’t look doomed. The tailors in Leah Gordon’s photographs have the settled air of people who know their worth, people who’ve mastered and made their living by a necessary skill. Necessary, that is, until recent history, when cheap second-hand clothes from the U.S. came flooding into Haiti, an unregulated and largely illegal import that began under John F. Kennedy. Hence the name for these second-hand clothes, kenedi, also known as contrabande—a nod to their smuggling origins—or more commonly, pèpè. The latter term also contains an origin story, as the tailor Ti Boss Thelius explained to Gordon: foreigners who arrived to distribute clothes in the wake of some long-ago disaster called out “pè, pè,” kreyòl for “peace, peace,” to signal their good intentions.

History shows the U.S. can ram pretty much any product it wants down Haiti’s throat, always in the name of good intentions. Iowa pigs, Arkansas rice, Georgia peanuts, and endless tons of cheaply produced castoff clothes all find their way to Haiti if Washington deems it should be so. In recent years the tailors of Port-au-Prince have seen their trade shrink to a few discrete niches: school uniforms, wedding gowns, ceremonial religious dress. Theirs is, very arguably, a dying trade, besieged by the grinding wheels of technology and global capitalism.

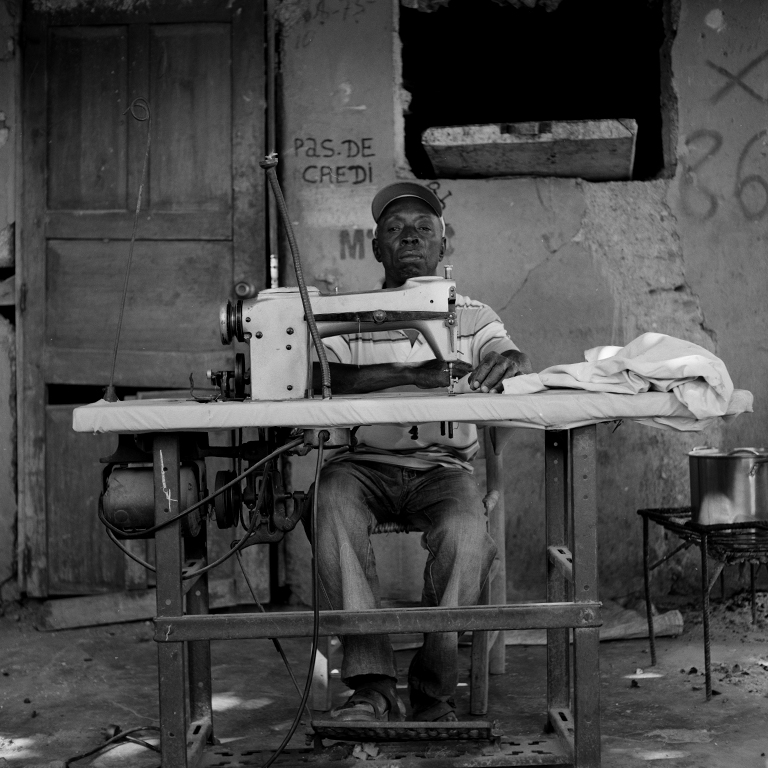

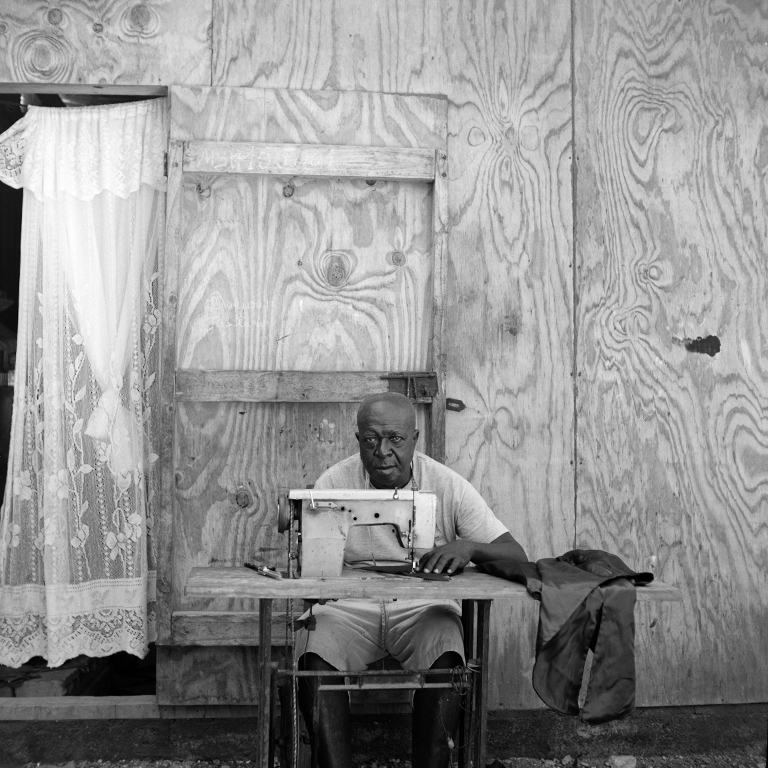

Yet the tailors of Port-au-Prince remain at their stations, and Leah Gordon presents them thus, each man looking up from his treadle sewing machine as if to greet a customer who’s just this moment appeared. Boss Thelius and Jean Bernadin offer welcoming, borderline beatific smiles; Claude Lafontant seems distracted; and the tailor Saintilus, with PAS DE CREDI—no credit—painted on the wall at his back, regards us like we’ve just asked for credit anyway. Gordon’s heavily shadowed and lined black-and-white photographs are rich with the details of work and daily living: a pot on a grill, family photos, hanging shirts wrapped in plastic, the weirdly evocative wood grain of a plywood shelter, abstraction bending, as abstraction always does, toward the literal, taking form as a giant spider hovering over the shoulder of the tailor Lafontant. But the centre of gravity in each picture is the tailor, his human face poised above the tools of his trade at a moment in history when tools and talent may no longer be enough for working people to survive. The oral histories gathered by Gordon bear this out anecdotally, and the numbers too, the wage vs. cost-of-living formulations that can be found in the latest crop of studies and news reports. With widespread digitization and mechanization, skills count for less and less, and in a globalized labour market where extreme poverty counts as “comparative advantage,” capital roams from country to country in a constant search for rock-bottom wages.

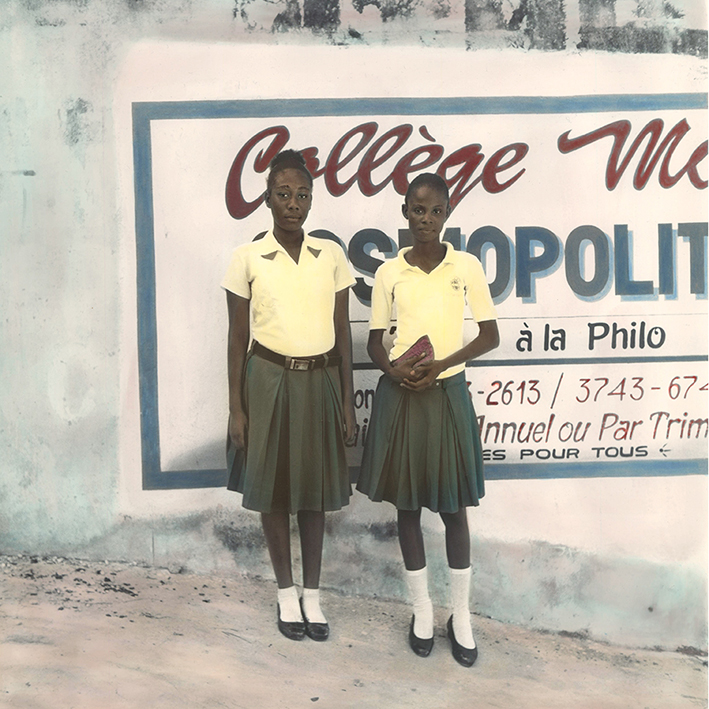

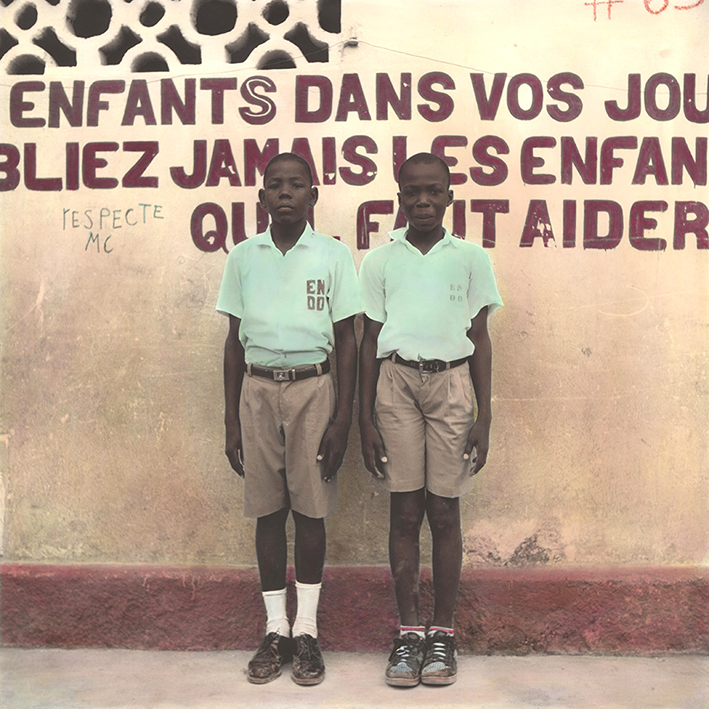

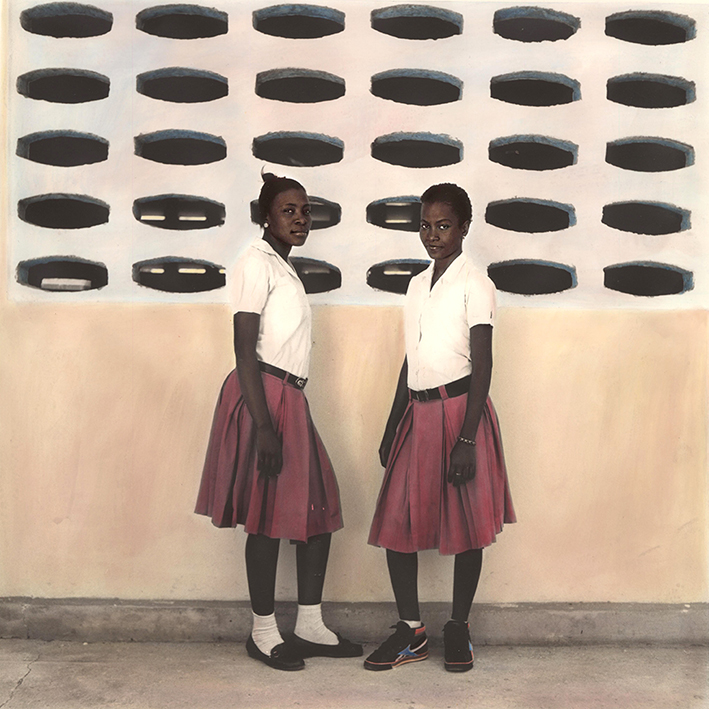

Gordon’s pictures are making a point—presenting an argument, if you will—about that most ultimate reality, economics. We—individuals, humans—are losing, and that creature called “the market” is winning. As for the students who wear the uniforms the tailors make, are they doomed too? You see them everywhere in Haiti, school kids grouped according to distinctive dress codes of plaid and stripe and solid, blasts of colour that call to mind the phrase “birds of a feather,” or visions of free-ranging flower beds. Gordon’s polemic underlies not only the content of her pictures, but her process as well. Each image in “Tailors” was shot on black-and-white film with a fifty-year-old Roleiicord camera, then developed and hand-printed by the master analogue printer Debbie Sears. With her photos of students, Gordon took the argument a step further by having the artist Marg Duston hand-tint each black-and-white print, a skill that’s practically disappeared in the last twenty years with the rise of digitization.

Is Gordon’s process mere conceptual gesture, or is there more at stake? The students are photographed in pairs—a pleasing tension takes hold as the eye bats back and forth, comparing, seeking out information—outdoors, in generalized, sourceless light, against backgrounds composed mostly of planes of solid color, with occasional fragments of signage or panels of breeze blocks. The stripped-down settings and smooth, shadowless light give a formality to these images that loosens their relation to time. The palette weighs toward blues and reds—the colours of the Haitian flag, incidentally—and there’s a textured, faintly tamped-down aspect to the colours, as if each print was treated with a rub of finely pulverized chalk dust. The eye finds traction in that texture. It pulls us in and simultaneously pulls something up in us, a sense of loss, perhaps, of time past—awareness of something we hadn’t known until this moment we’d lost? It’s in the distancing effect of those muted colors, the insistent hint of the artificial, of mediation. Perhaps the labour-intensive processes with which Gordon invests her images are what’s needed to bring us closer to true perception, to the kind of knowledge that the eye doesn’t so much see as feel. Knowledge that transforms an image from document into experience.

“What will become of all this beauty?” James Baldwin once asked on encountering a classroom of elementary school students. One can’t help but wonder what will happen to these beauties, these young and old and middle-aged Haitians who Leah Gordon presents in all their frank humanity. Haiti is a hard place; harder than most, which doesn’t mean our fate is any less bound to theirs. Throughout its existence Haiti has been on history’s leading edge, and we see it happening again in the radically changing economies of technology and work. The grinding wheels that are working on Haiti, on its tailors and beautiful youths, they’re working on all the rest of us too, albeit with the luck of a slightly more or less delayed timeline.

For more of Leah Gordon’s work, click here.

For more from our Ideas Series, click here.

To sign up for membership and receive our latest issue of the Photoworks Annual, click here.