Judy Harrison describes the making of her book Our Faces, Our Spaces: Photography, Community and Representation, a collection of photographs produced at the Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop since the late 1970s.

My book, Our Faces, Our Spaces features photographic work taken between 1977 and 1992 by children and young people who were members of Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop in Southampton.

The book presents the participants’ work within the context of their personal experiences alongside essays from critical and theoretical perspectives. The photographers offer a view and interpretation of their world, which deals with the social, cultural, religious and political connections of that period of time.

Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop was established as an organisation in 1982, latterly known as The Media Workshop, and sadly closed down in 2013 due to funding cuts, thus becoming arguably the longest community photography workshop in existence within the UK.

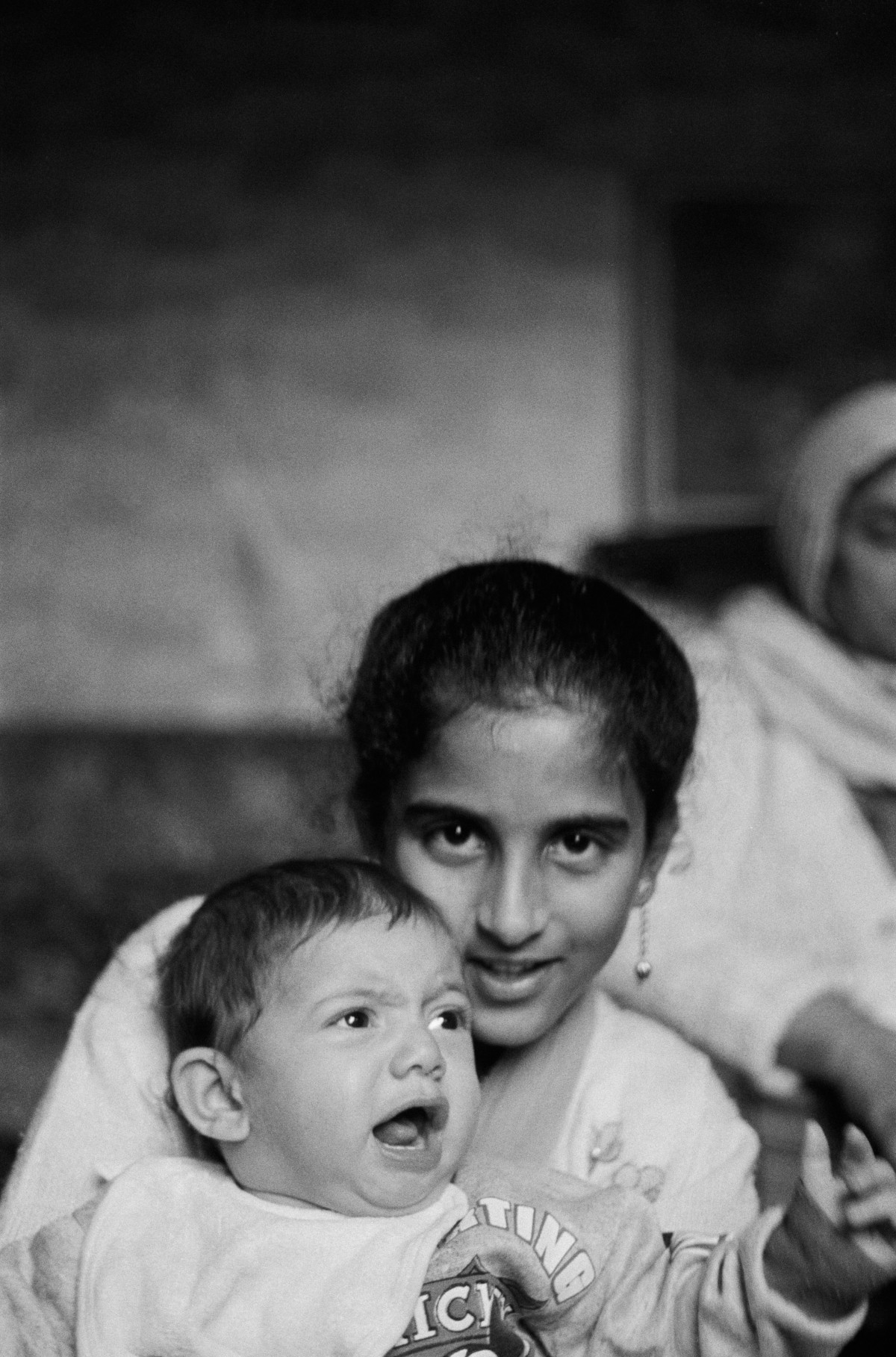

The project began in 1977, through an Arts Council funded fellowship based at The Photographic Gallery within the University of Southampton. Through this fellowship I initially worked within a school in Southampton with groups of children between the ages of 8 and 12 who were mainly from Asian backgrounds. The children were taught how to take photographs, how to print in the darkroom and how to produce their own photographic visual resources which could be used within their own educational learning.

The project grew over the next ten years into a large community photography resource known as Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop, and became, as Charlotte Cotton has described:

‘A place that empowered hundreds of young people and their families to use photography as their tool for positive social change, and to express their imaginations.’

It was a unique project that, over time, created a platform for marginalised communities to tell their stories. Children grew up with the project, through adolescence into adulthood, being participants and taking ownership of management and responsibility for the organisation. It was a project that challenged photography’s traditional power structures, creating a space for young people to react against racism and the marginalisation of black and minority ethnic communities during the Thatcherite years in which they grew up.

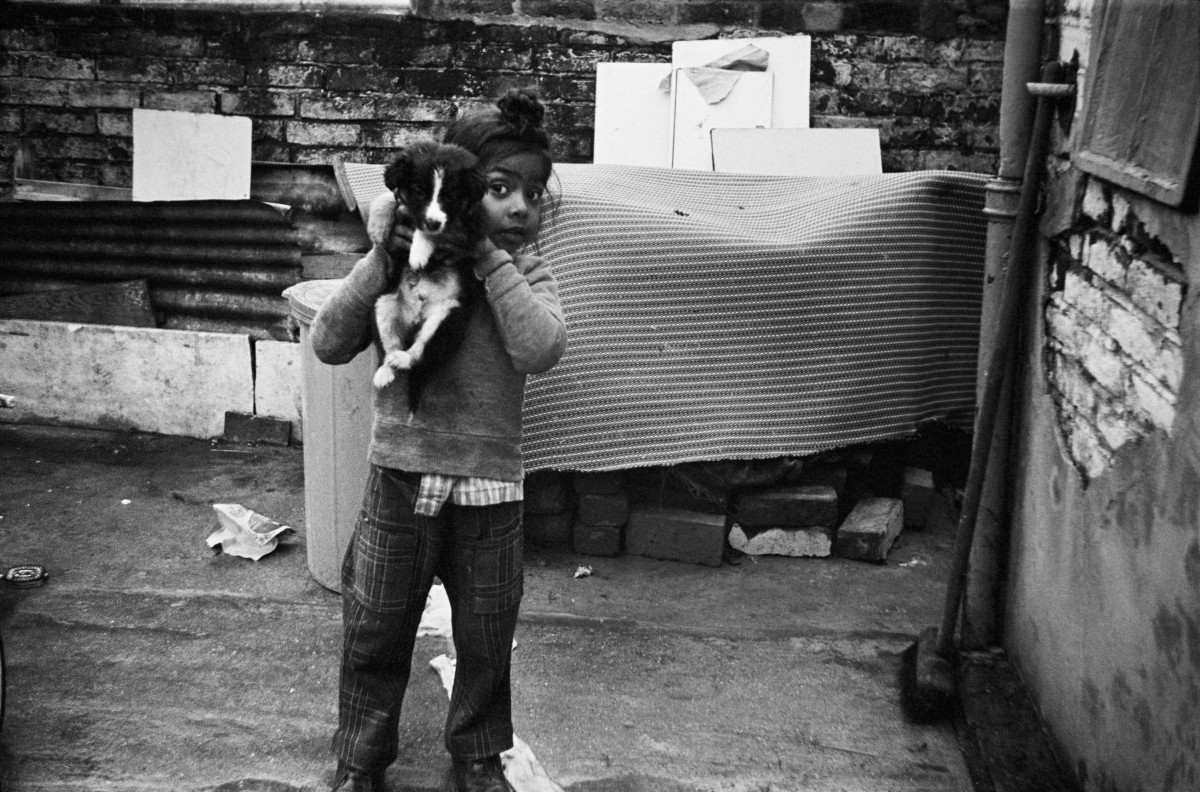

The ownership of a camera gave the children and young people a freedom and confidence to access the street as their own open studio. The politics of space, which had previously been marginalised and denied to them, suddenly seemed to provide a reason and entitled a right-of-passage to step outwards with their cameras, utilised as a shield – almost, metaphorically speaking as a war photographer would strike forward into a war zone. They made the invisible visible. The backdrops of walls, pavements, streets, lamp posts and exterior doors provided an additional space away from the safe, domestic spaces of the home.

Just as The Workshop grew in a tactile way, compiling the book became a collaborative project in its own right. It was a recall of the participants thirty years later to reflect on their images and to look back on their experiences.

What I think is so powerful is the participants’ own reflections and thoughts of their photographic practice, and how it affected their self esteem and confidence. The value of respect, ownership, community collaboration, control and the process that it entails are what they all comment on. They now talk about how cathartic it was writing these essays and how they themselves have pieced together the elements of utilising photography and how that experience has filtered through their lives to becoming parents, grandparents and the role that they themselves play within society today. The memories of racism and how they, growing up, used photography to challenge this – to be seen and heard – comes across powerfully within their statements.

As Sucha Singh Digwa recalls in one of the book’s accompanying essays:

‘It was a very political project; we didn’t think of that at the time but obviously it was. We displayed our work at galleries and were empowered; this was our outlet to express ourselves.’

And David Singh Roath explains:

‘I think photographs tell a story and, in this case, it was our own story…..The Workshop grew and that was important – it was inspiring and touching people’s lives. It was at the heart of the community and that took years to build.’

Their essays stand on a par with the more theoretical writings and interviews by the renowned theorists and practitioners Sunil Gupta, Sian Bonnell and Christopher Pinney. The two styles weave together in a seamless way, both reinforcing and contextualising the other. This is what makes this book unique for me and is an outcome that I had never imagined. The book itself now holds pride of place within the communities of many of the homes, and gurdwaras, where many of these photographs were originally taken, some as far back as forty years ago.