By Hannah Geddes, 24 October 2025

Decomposition is not failure, but part of the life of the image: a cycle in which birth, wear, and disappearance are inscribed in its materiality. Filipa Frois Almeida

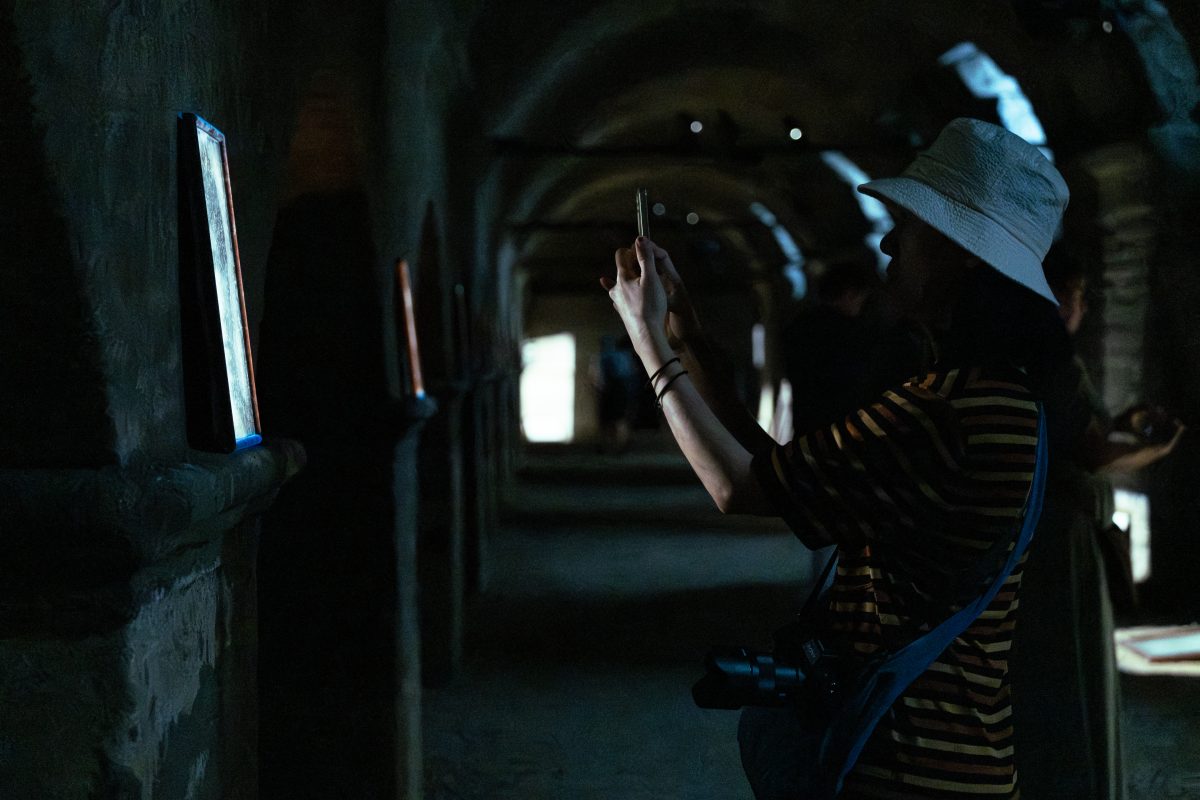

On a boiling hot day in the South of France during Rencontres d’Arles 2023, I descended the stairs into the cryptoporticus, the underground Roman vaults dating back to 1st Century BCE. While being a momentary respite from the sunshine, it was also the location of Sophie Calle’s exhibition ‘Neither Give Nor Throw Away’, an array of photographs alongside an installation of clothes and objects that unfolded throughout the damp and dark tunnels of the crypts. That same year, while preparing for her retrospective at the Picasso Museum in Paris, an unexpected storm damaged Calle’s storage place, causing tiny mould spores to infiltrate her photographs – spreading across the images as if infecting them. As the mould spores would not only damage the works in storage – they would also infect any new photographs that came into contact with them – the conservation team advised that Calle destroy the works to limit further destruction. Rather than dispose of them immediately, Calle came up with a new idea to display them a final time in the damp and dark crypts during Rencontres d’Arles, finding beauty and new life in the process of their decay.

I noticed that the rot had carefully chosen its victims. Besides the Blind, it had only affected those works that spoke of death or loss, as if their imperviousness were already compromised…

The site of the crypts became the final resting place for these works – the last time they would be shown or seen by anyone. Amongst the damaged works were her series the Blind, as well as photographs of gravestones taken in a Californian cemetery. Calle engages with themes of mortality and ageing, as well as our inherent desire to resist our inevitable fate. Alongside the decaying images, Calle included items that while she no longer used, she could ‘neither give nor throw away’ – her wedding dress and a mesh outfit from her fiftieth birthday – both reminders of the passing of time. Exhibiting the decomposing photographs alongside remnants of a past life, Calle comments on our inevitable mortality and the impermanence of life, while also suggesting that new meaning can emerge in the spaces in between. By creating a ritual around the decay of the images, she reminds us that there is beauty and life in ageing.

Inspired by Calle’s ability to find new meaning in the decay of her artworks, I am exploring notions of impermanence and ageing in photography. Through bringing together artists who challenge traditional notions of preservation, I argue for the need to begin to welcome the ageing and decay of images as a disruption or resistance to some of the more limiting structures of the archive. In allowing space for the ageing of the image – alongside the necessary care and preservation of important stories and histories – we might look toward more sustainable and generous modes of image-making. As artists turn toward ethical and sustainable methods in response to the oversaturation of images, the rise in AI-generated photographs and increased digital manipulation, I ask what it means to let an image age, for it to decay and have its own life cycle.

The archive is an inherently contradictory space: it can be a space for liberation and dreaming, where collective stories of history are preserved and cared for. As curator Vasundhara Mathur explored in The Archive is a Gathering Place symposium at Tate Modern in 2024, collective archives ‘arise out of a necessity to document, preserve and mobilise histories, dreams, testimonies and practices that might otherwise be lost or face active erasure’. Or as Tina Campt explores in her book Listening to Images (2017), new dialogues and connections might emerge with subjects in archival images if we learn to connect with our senses, to ‘move from vision to sound by way of touch.’ Ariella Azoulay also calls for alternative models of engaging with archives, asking us to ‘watch’ rather simply look at photographs, while Saidiya Hartman employs critical fabulation to creatively reimagine silences and omissions in archives through the fictional retelling of Black women’s lives in her book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019). While these examples point towards new methods for reimagining archives, they can still be spaces where stories are obscured or mis-told, where photographs are buried, left hidden and forgotten. Similarly, when photographs enter into museum and galleries, they become part of complex networks of care and preservation, processes that above all are designed to ensure that photographs survive, that they are protected for future generations to come. As Calle discovered when it was suggested that she destroy her own damaged artworks, there is beauty and humanity in impermanence. By engaging with alternative models of preservation and ownership, we might begin to create more positive relationships with ageing and decay. As digital photographic storage contributes to increasing levels of carbon emissions, can welcoming impermanence and decay also create more sustainable and ethical photographic practices?

Alongside Sophie Calle’s exhibition Neither Give Nor Throw Away, I am bringing together artists who seek alternative relationships with artworks by exploring tactility, sustainability, decay and renewal in the work of Clare Hewitt’s project Everything in the forest is the forest, Liz Johnson Artur’s Time Don’t Run Here, and Filipa Frois Almeida’s project Mergulho em Apneia (Freediving). Conceptual artists have long been working with organic materials in their work, exploring themes of decay and transformation. Scottish artist Anya Gallaccio works with organic matter and ephemeral materials that naturally decay over the process of being displayed. Her installations often smell of rotting fruit depending on when you encounter them, featuring organic materials such as flowers or fruit that slowly change and decompose over the course of the exhibition. While French artist Mélanie Matranga’s exhibition 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, at Nottingham Contemporary in 2021 included flowers and fruit that naturally decayed over the duration of the exhibition, exploring the temporary and sometimes fragile relationship with our surroundings. Often used to protecting and preserving artworks, these processes and use of materials challenge conservation and curatorial teams to work differently and shift our connections and relationships to how we keep and display artworks. Artists are also using their work to challenge the practices of ownership and longevity, evident in the work of Kaqchikel artist Edgar Calel’s installation The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge (2021). Consisting of fruit and vegetables sitting atop of rocks as offerings to the land and his ancestors, he explores Indigenous experiences through his Kaqchikel heritage. In the Mayan tradition, objects are not owned and instead, individuals or groups become custodians on behalf of the community. Reflecting Calel’s belief that ‘not all things are for sale’, rather than owning the work, Tate became custodians of it, promising to care for it for a period of thirteen years from 2023. Resisting the need to own and preserve artworks in perpetuity, he holds space for impermanence and temporality while creating new institutional processes of preservation and care.

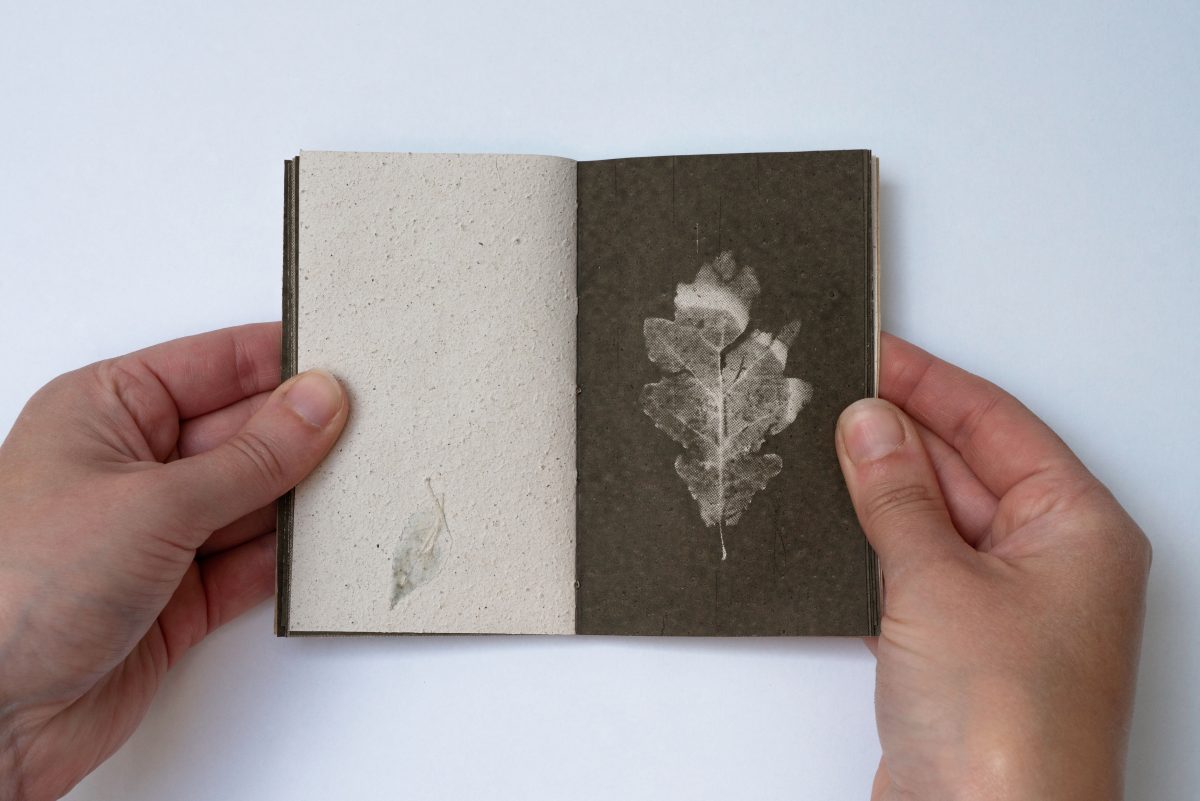

Artists working with photography are also challenging notions of ownership and preservation, exploring ecological alternatives to how we engage with and share images. British photographer Clare Hewitt’s recent project Everything in the forest is the forest explores symbiotic relationships at the heart of our forests. After reading a report in 2019 that revealed the rates of loneliness in the UK and learning that trees thrive in communities, Hewitt turned to the forest to see what she could learn from observing and understanding the relationship between twelve 180-year-old oak trees at the Birmingham Institute of Forest Research. Designing 24 wooden pinhole cameras, she fixed them to the oak trees to record them over a number of years. Through the project, Hewitt ‘reimagines what photographic practice can be, materially, ethically and socially’ by observing the ‘connection, care and intelligence’ within the community of oak trees. Observing the cyclical nature of the trees – that everything the trees produce returns back to the environment – she began to explore whether she could mirror this ecological regeneration through creating a sustainable photobook. Working collaboratively with artists Danielle Phelps, Carolyn Morton, Alice Fox, and book designer Emily Macaulay of Stanley James Press, they created a biodegradable photobook featuring ‘paper made with mushrooms, screen printing ink made with oak galls, and allotment grown spun linen thread’. Responding to the reciprocity she witnessed in the forest, and challenging ‘extractive mode of making’, Hewitt created a distribution system that rejects the notion of single ownership and instead focused on borrowing and sharing amongst recipients. To make this possible, the book was designed in 12 parts or ‘mini-books’ so they could be distributed and shared. Instead of owning the book, recipients signed up to borrow it for a week before passing it on to the next ‘custodian’, sharing similarities with Calel’s practice of temporary custodianship in The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge. These ideas reflect the life cycles of the natural world and challenge us to think about temporality and ageing as inherent to an artwork’s lifespan. They also disrupt capitalist models of extraction and ownership, pushing us towards more reciprocal and generous models of care. As Hewitt draws attention to – like the lifespan of the forest – the biodegradable photobook is designed to return to the natural world that it emerged from, creating a book ‘rooted in reciprocity, responsibility and ecological awareness.’ Through working closely with the forest and observing the intimate and collective ecosystem, Hewitt’s project presents photography ‘as a living system: responsive, inclusive and circular’ allowing ageing and decay into the work as a natural part of the life cycle, while resisting notions of extraction, ownership and preservation at the heart of capitalist systems. Responding to our ongoing state of ‘social fragmentation and environmental crisis’ Hewitt suggests that ‘we can and must create differently’.

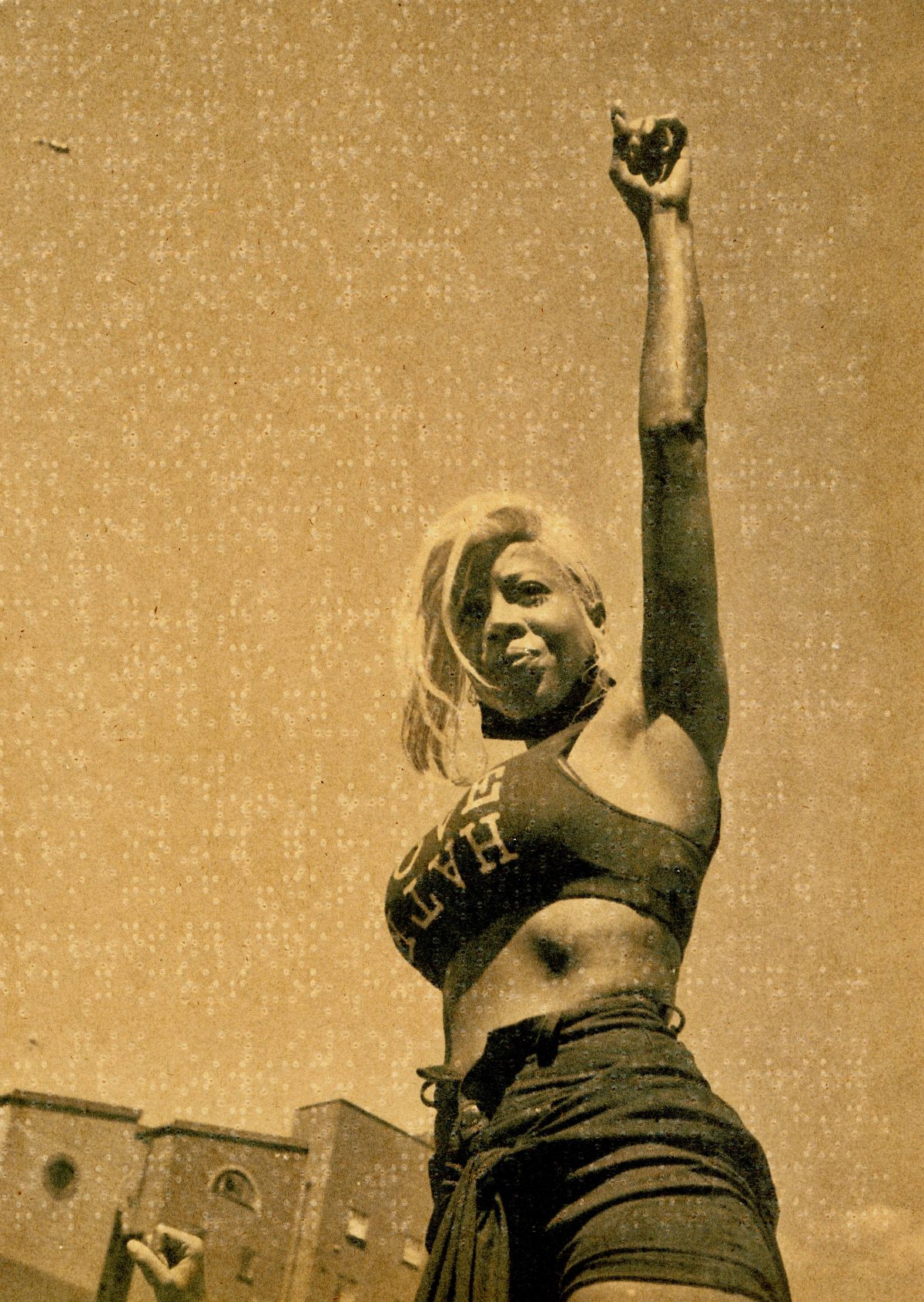

While artists have been working with organic matters and materials in contemporary art, notions of decay and temporality are more challenging in relation to photography. The photograph is a fragile item, always at risk of damage due to light – its very existence is its own fate. Museum conservation processes ensure that photographs are only on display for short periods of time – rotated out and back into storage. While this is a necessary process in the care of artworks, it can limit our tactility or intimacy with images. Russian-Ghanaian photographer Liz Johnson Artur works across photography and the archive, developing her ever-growing Black Balloon Archive that documents life across the African diasporas – mostly in London where she lives and works. Artur has amassed a vast collection of workbooks over the years, handmade volumes that she has developed since the 1990s. The workbooks are full of collaged images – pasted, cut and assembled as a way to archive and document ‘not only images, but life itself.’ There is a tactility and intimacy to the workbooks as we see life through Artur’s lens. As Artur explains to Gem Fletcher in the Messy Truth podcast, there is an intimacy to her work that she strives to bring into institutional spaces, ‘it’s not made for a white walled space where everything is organised and presented in a precious way.’ Artur’s project Time Don’t Run Here (2020) consists of photographs taken at Black Lives Matter marches across London in 2020. The photographs are all printed on braille editions of Iris Murdoch’s The Red and the Green (1965) and John Harris’s Ride Out the Storm (1975) as a comment on how information ‘became obscured and misunderstood’ during the protests. The braille also draws attention to the tactility of the images, and the intimacy that Artur is striving for in her photographs. This desire for tactility and connection resists conservation and exhibition practices, the process of putting works behind glass or barriers, restricting viewers coming too close or touching images. As Artur explains to Fletcher, in contrast to exhibiting works, ‘The book is a good example of what happens when things live with you. You know, they get tears, they get scratches, they get all these things’ and like Calle’s images – there is a beauty in the wear and tear that is part of life. This intimacy and touch resists the way we mostly consume and share images today, as we are separated by a screen, our fingers swiping mindlessly left and right. Artur is always playing with the way that we view and interact with images, her installations are always shown at eye height so we can actively engage with the subjects in the image, printed in a way that might make ‘you want to touch’ or to ask what ‘does it feel like’? The ability to handle and touch artworks means they start to decay quicker, but there is also something liberating about resisting the need for things to last forever.

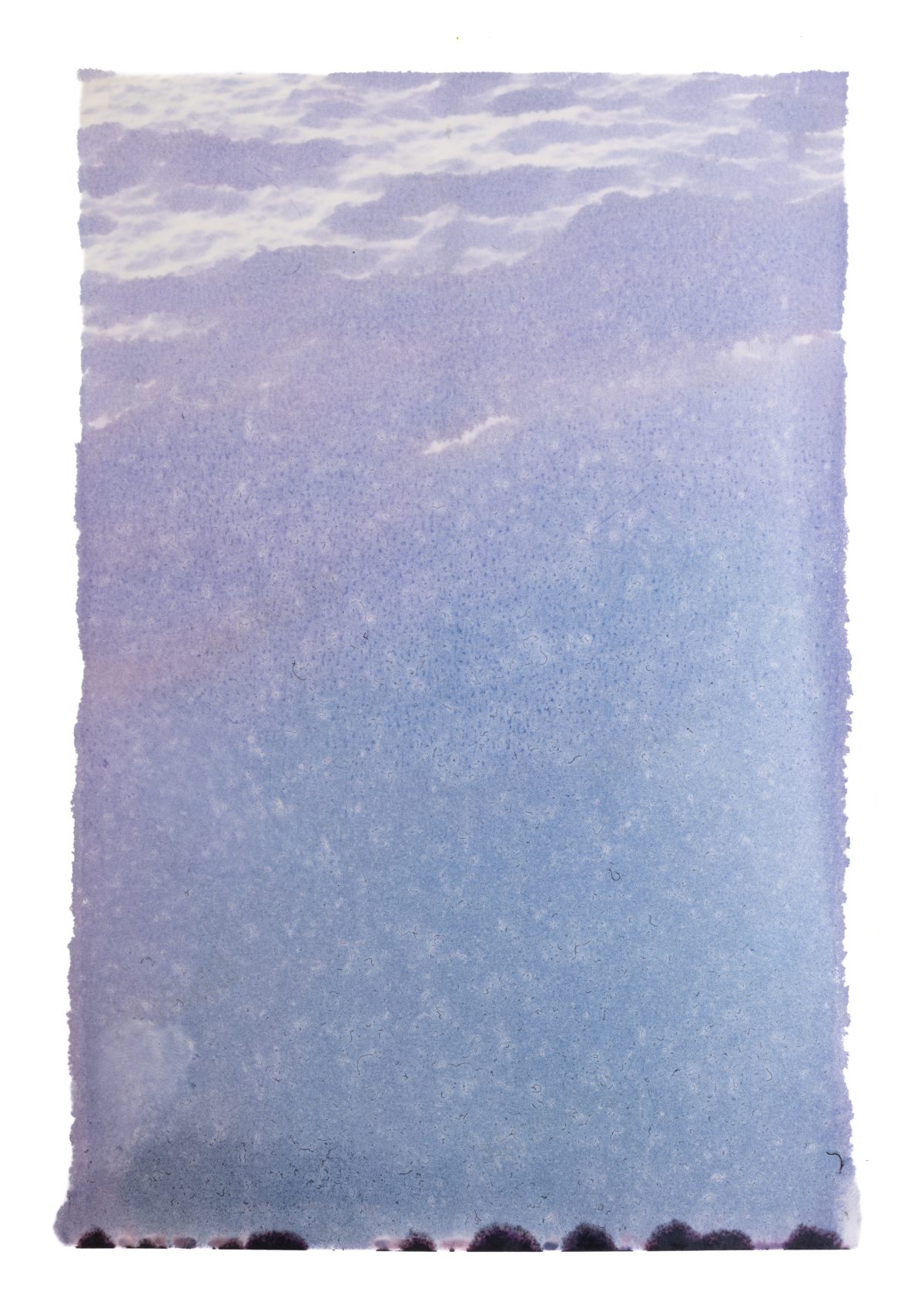

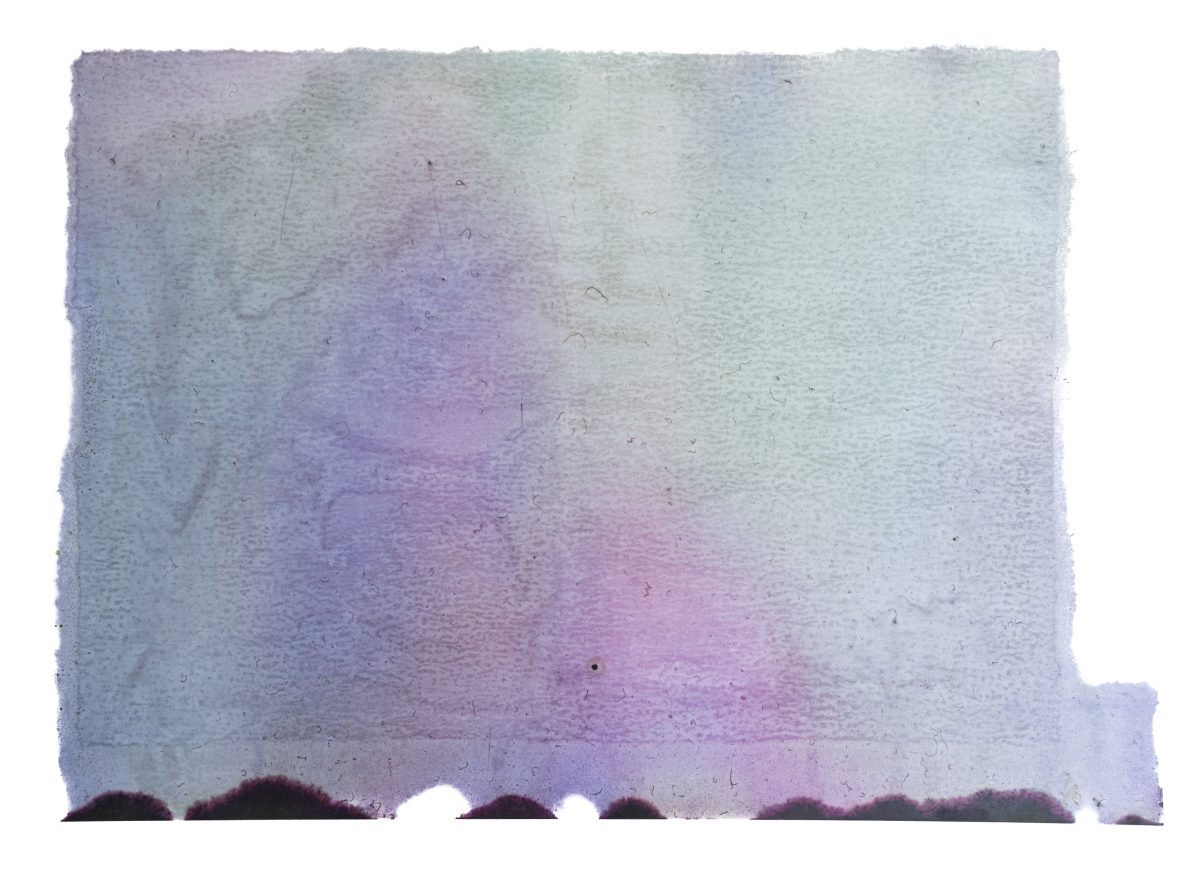

As Calle suggests in Neither Give Nor Throw Away, there is beauty to be found in decay and temporality. As we move into ever more digital realities, with AI and digital manipulation forcing us to question every image that we encounter, artists are exploring alternatives methods that celebrate the natural life cycle and ageing of the image. Filipa Frois Almeida is a Portuguese visual artist and researcher exploring the representation of time and memory through analysing the deceleration of the image. Her project Mergulho em Apneia (Freediving) results from tracing the decomposition of photographs over a two-year process. Printing the images on non-absorbent paper, the images remain unstable, causing the ink to run. Resisting the need to preserve or fix the images, she photographed their transformation over time as they were exposed to the environment. Using images from her family archive, she was less concerned about preserving their likeness and more interested in ‘how time corrodes, stains, and transforms, leaving traces that function as signs of what can no longer be recovered.’ As Almeida explained, the inspiration behind the title of the work is Hans Blumenberg’s nautical metaphor in Shipwreck with Spectator. Using it for the project, she suggests that instead of being a form of fixing the visible, photography stays in motion, always in a state of transformation.

Almeida’s images take on a new life, with slight traces of the image that was once there before. Pink and blue hues drip down the page, becoming abstract representations of their past identities. It is in this process of transformation that Almeida begins thinking about ‘photography as both poetic practice and sustainable gesture, in contrast to the speed and obsolescence of digital imagery.’ This is also a form of resistance against the preservation of images in the digital sphere – the fixing of something that lasts forever. Through experimenting with the decomposition of the image and welcoming the instability, she ‘proposes a more attentive, patient, and responsible way of looking at what we produce and preserve, situating photography within an ecology in which creation and decay are in balance.’ This resistance to ‘the digital logic of infinite production and accelerated circulation’ points to more sustainable methods of production, and the desire to hold space for temporality in photography, something more akin to the natural world. This connects back to Anya Gallaccio’s use of organic materials in her work as a way to resist the preservation of artworks, demonstrating how artists are pushing for more sustainable ways of working.

As these artists have drawn attention to, there is beauty and freedom in welcoming the ageing and fragility of the image. While the archive is an important and powerful place to hold stories and testimonies of the past, artists are also looking towards alternative futures for engaging, sharing and owning photographs, welcoming the natural process of ageing and decay. There is an intimacy and beauty in the wear and tear of life, and as photographers have to contend with the increasing digitisation and manipulation of the medium, these artists offer us alternative models that centre reciprocity, tactility and care in the letting go of our inherent need to make things last forever. As we continue to become submerged in the rapid circulation and consumption of images, creating endless archives of digital images consumed through our screens, these artists are finding new ways to resist. Through encouraging intimacy, connection and decay, they suggest there is a more sustainable and generous way to care for and engage with artworks, one that celebrates the beauty in the fleeting moments that are key to our temporary existence.

Hannah Geddes is a curator, writer, and researcher based in London. She currently runs the talks, residencies and young artist programme at ICA and is curator at Splash and Grab Magazine. She is also pursuing a PhD at UAL and her research, Tracing ‘messiness’: artists as catalysts for the collective in contemporary photography explores collaboration and messiness as feminist strategies in contemporary photography. Her writing has featured in a number of publications including British Journal of Photography, JAWS Journal, Ardesia Projects and Splash and Grab.