An excerpt from FOLK, by Aaron Schuman, published by NB

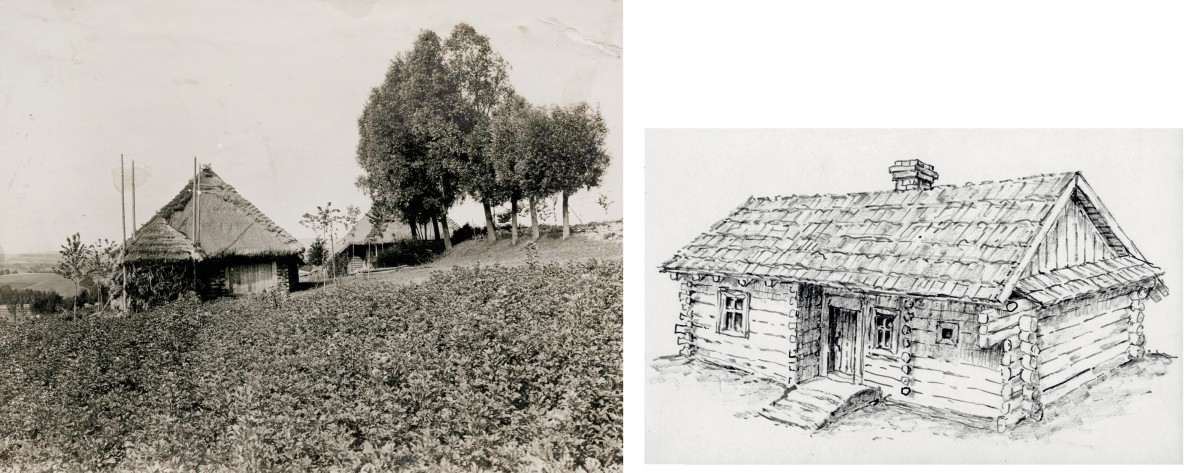

In 1878, my great-grandfather – Franciszek Feret – was born in Cierpisz, a small village approximately 150 kilometers to the east of Krakow. In 1900, at the age of 22, he left this region of Poland (then known as Galicia) and emigrated to the United States.

More than a century later…I was invited to curate Krakow Photomonth 2014. I proposed the theme, “Re:Search”, and soon discovered that one of the participating exhibition venues was the Ethnographic Museum in Krakow – an institution that I had visited earlier in the year, and completely fallen in love with…

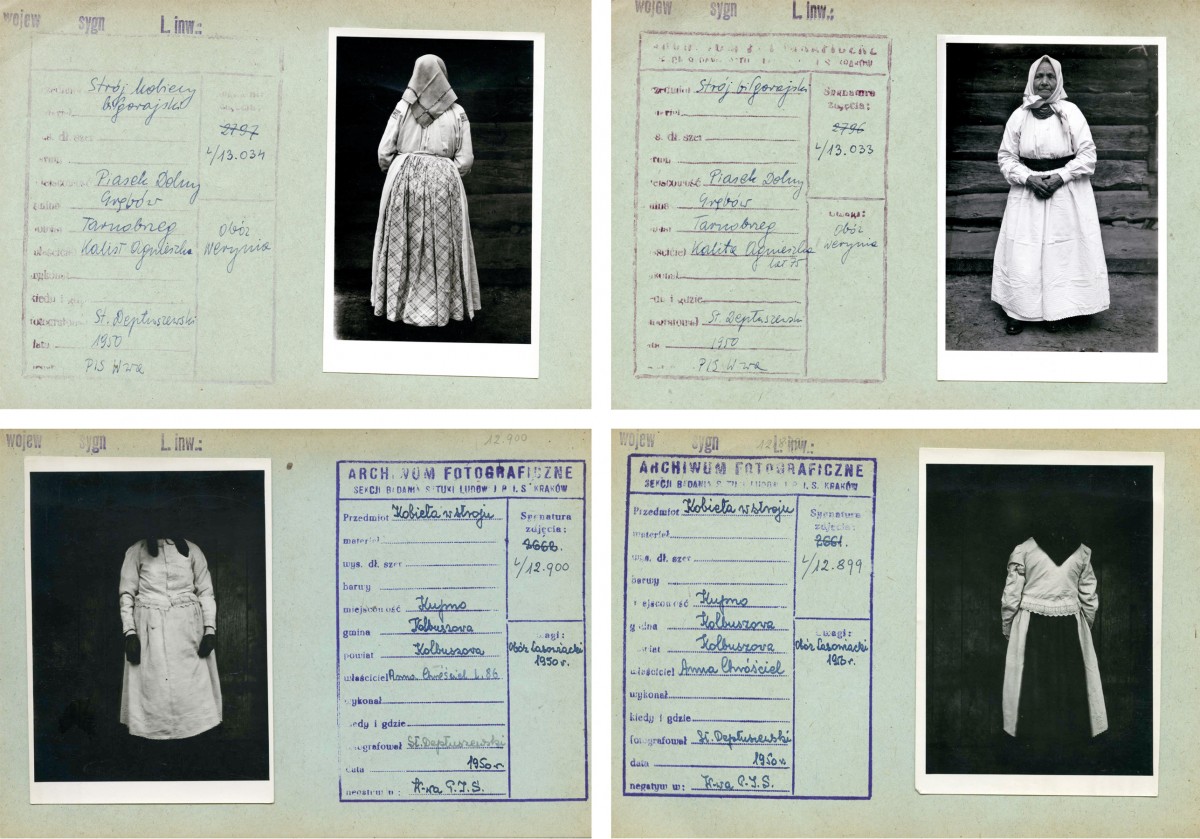

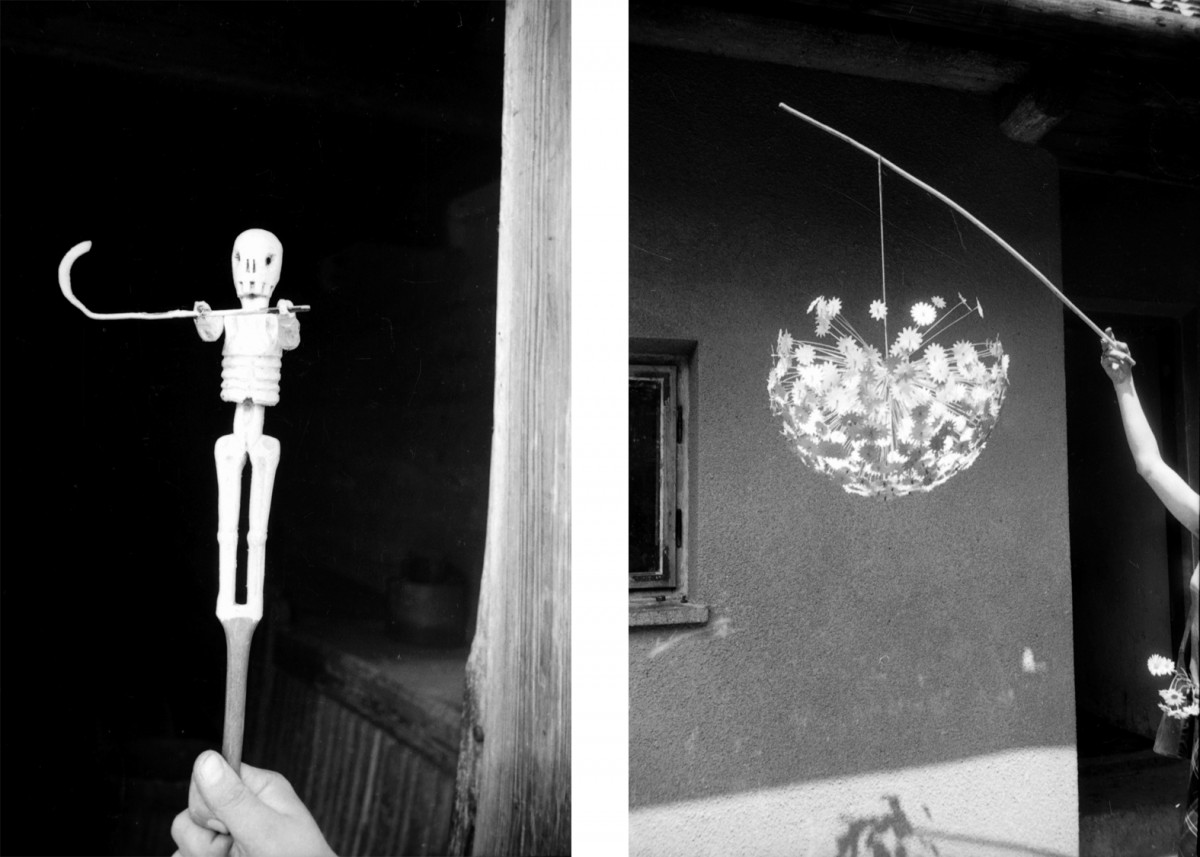

In January 2014, I explored in great depth the displays, collections, storage facilities, libraries, and archives of the Ethnographic Museum. Ewelina Lasota, one of the museum’s research assistants, accompanied me as I met with the longstanding curators and archivists, all of whom had located fascinating material from the region where my great-grandfather had come from, and artifacts associated with the ethnic group—the Lasowiacy, or “forest people”—who once lived there. During this time, I learnt a remarkable amount about my own Polish heritage. But in the process, I also became equally fascinated by the history and culture

that thrived within this century-old museum itself—the “museum people,” so to speak—and found myself feeling as connected and related to them as I did to

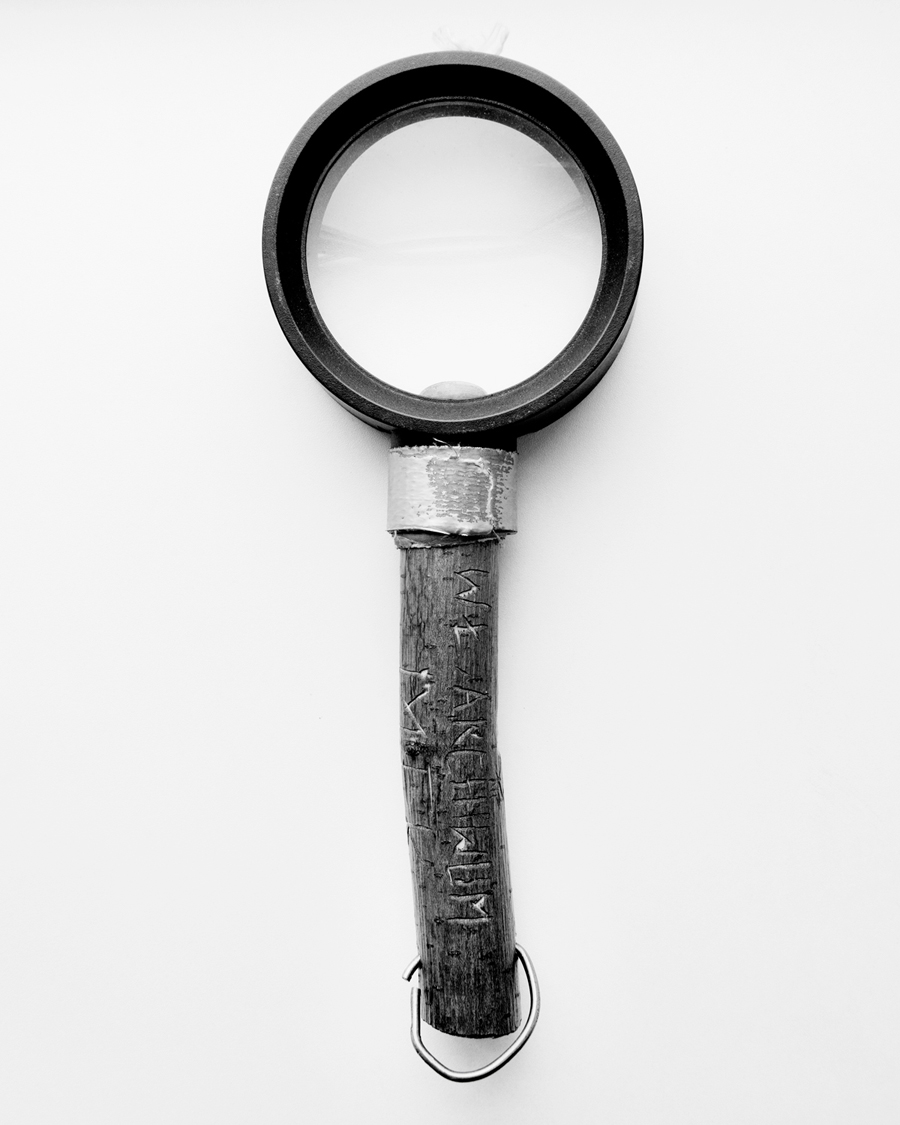

my own great-grandfather. More and more, I was gradually drawn to the people, objects, artifacts, and images that subtly revealed something about the history and culture of the museum as a place, and of ethnography as a field of study itself. I became intrigued by the site-specific customs, behaviors, and traditions that were quietly represented in the smallest of details, and in fact, I often recognised myself and my own behavior as much within these artifacts—the snapshots, handwritten notes, catalogue cards, old storage boxes, and so on—as I did in the original objects from Lasowiacy culture…

————

From: Ewelina Lasota

To: Aaron Schuman

Subject: VERY kind request

Date: 28 February 2014

Hi Aaron.

I just met with the Director. I introduced him to the objects that you selected for your project. I will try to do my best to explain our conversation, but because my English isn’t perfect, I would like to apologise to you for any understatement. If anything arouses your concern, please write to me.

Firstly, we want to thank you for your commitment. We are pleased that we can work together to realise the project, which will be both about you and about the Ethnographic Museum in Krakow. Questions that we would like to ask you could seem strange, but we would like to understand correctly the selections you have made. Please do not take our standpoint as an attempt to censor you. No, it is not like that. We want you to feel free in your artistic expression. But to understand your way of thinking, we also want to know the general message of the project, the logic behind the objects you have chosen, why you have decided to include these things, and what do you want to tell through their prism?

In some ways we agree with choices you have made, because we also use historical objects from the collection. But in some ways we don’t agree, because we don’t like to use these things as relics; we try to show them within contexts of contemporary life. Each one is rooted in the present.

As a museum team we have already done a lot to get out of a narrow understanding of ethnography as folk – a process of change that started here a few years ago.

Aaron, I’m sorry if we are hypersensitive. We just would like to make sure that we understand the message of the project, since we are a part of it. Maybe you could send us a statement, or specify what you would like to say through the selected items—about yourself and about the museum?

Thanks for understanding.

Ewelina Lasota

The Seweryn Udziela Ethnographic Museum in Krakow

————

From: Aaron Schuman

Subject: Re: VERY kind request

Date: 3 March 2014

To: Ewelina Lasota

Hi Ewelina,

I will try to explain the best I can the themes and intentions of the project –and the thinking behind it—as clearly as possible. Firstly, the title of the exhibition: FOLK. In English, the word “folk” has several meanings:

– members of one’s family (especially one’s parents, grandparents, and direct lineage);

– of or relating to the traditional art or culture of a community or nation;

– relating to or originating from the beliefs and opinions of ordinary people;

– down-to-earth, unpretentious people;

In terms of my project, these definitions are incredibly relevant. First and foremost, my journey and fascination with the Museum started with a genuine interest in the region and culture that my family—my “folk”—came from. As I explained when I initially proposed the project, what interested me when I first visited the museum in June 2013 was that so much of the material was both vaguely familiar to me, and also very exotic and foreign. So it was a very strange experience, because culturally it all felt like something new, fascinating, and far away, but also very close to me in ways that I didn’t really understand.

Secondly, I was deeply fascinated by the spirit and mission of the museum itself; the fact that, over the course of more than a century, such an incredible investment and effort has been directed towards the preservation of traditional arts and cultures of “ordinary people,” and has been done so with such incredible passion and care on the part of the ethnographers, archivists, and curators that have worked there, both past and present. Furthermore, I discovered that the way in which the Museum exhibits and presents this material, and educates its visitors, was remarkably open, friendly, and accessible—not only does the museum focus upon, preserve, and celebrate the traditional, “down-to-earth,” “unpretentious” art and culture of “ordinary” communities in the region, but the atmosphere and feeling of the Museum itself and the people whom I encountered working there—the “museum folk”—were also strikingly “down-to-earth” and “unpretentious.” In yet another sense, I felt as if I had found my “folk.”

So both the title and the focus of my project are directly linked to the multiple meanings of the word “folk”—as it relates to notions of family and heritage (my own); as it relates to the founding intentions and continuing spirit of the museum itself, which focuses on traditional art, culture, and beliefs of “ordinary people” (as opposed to the royal, rich, and powerful); and as it relates to my own experience of the museum as a place full of its own traditions, people, culture, and atmosphere that is “down-to-earth” and “unpretentious.” In every sense, I am taking the Director’s own philosophy to heart, and exploring the museum as he describes it on your website, as a “center of reflection and understanding oneself and others.” I have reflected upon and learnt about myself and my own origins, but I have also reflected upon and gained understanding about others—my ancestors, ethnographers, curators, and the culture and community of the museum itself…

My experience of researching my family’s cultural origins within the Museum was not one of staring at a computer screen, combing through hard-drives and looking at digital data (like so much research within institutions is these days)—it was one of opening up the drawers of card-catalogues, reading through hand-written and hand-typed cards, looking at drawings and black-and-white photographs, breaking wax-sealed doorways, opening up old shoeboxes and crates, dusting off and investigating objects with hand-tied, hand-written labels, talking to incredibly knowledgeable people who have been working with these materials for forty years and know them intimately, and so on. I understand that the Museum is changing dramatically, and for very good reasons. This is incredibly important for its future. But my project is not intended so much as a representation of “how the museum sees itself” (and its future), but more of a reflection upon “how I saw and experienced the Museum myself,” and an exploration of how these museo-cultural “relics”—despite being seemingly outdated—still exist, resonate, and inform the museum in the present and in its most contemporary form. They are the “folk art” of the museum itself; they bear the physical traces of its traditions and history, and like the objects held in the collection, they contain important information that deserves to be considered, explored, and celebrated as the museum evolves and transforms in the twenty-first century. Like so much of the culture that is preserved by the museum itself, they sit at the foundations of contemporary experience, but they may also disappear (in their purest form) very soon.

I really hope that this will help clarify my intentions…My project is intended to both engage with and explore the museum, its history, and the history of its discipline (ethnography) from a very personal, creative, unexpected, and relatively fresh perspective, and I believe that the fact that I have been invited to collaborate with you in such a way testifies to the Museum’s forward-looking approach. It goes to show that the museum is genuinely a “center of reflection and understanding oneself and others.”

All the best,

Aaron

————

In April 2014, the Ethnographic Museum’s Research Coordinator, Magdalena Zych – along with her husband, Andrzej, and Ewelina – picked me up early in the morning, outside of the museum, and drove me to Cierpisz…I tried my best to connect with the place, knowing that my ancestors had once walked in these woods; that they had lived, worked, loved and died here, just beside this small river. I even reminded myself that, if it wasn’t for my great-grandfather, I – or at least some version of me – may still, in some way, be here. Nevertheless, the echoes of my family’s past, although present, seemed distant, muffled, and very faint. Despite my verified ties, I still felt like a stranger to the place; it made perfect sense that I, with camera in hand, was more at home in the car with the researchers and ethnographers – with my folk. The day after returning to Krakow, Magdalena wrote to me:

From: Magdalena Zych

To: Aaron Schuman

Subject: after Cierpisz

Date: 3 April 2014

Dear Aaron,

Since our trip to Cierpisz yesterday I’m thinking about different things around searching in present time, and in memory. In your choice of photographs, I saw one or two sickles. The sickle was used by women, the scythe by men. They were personal tools. In the Polish language, we call a moon like we saw yesterday evening, “sierp księżyca” – it means “sickle of the moon” (crescent). It’s very common to say that.

With the miller, there were some superstitions. Because they had different way of life, they were often considered a stranger in the local community. They didn’t work in the normal, farmer way. They did a different job, however very important. It is why sometimes people were thinking that the miller was helped by the devil—the miller’s soul is given to him In ethnographical sources from the nineteenth century we have some examples.

My great-great-grandmother, Maria Obara, was in the USA twice as a young woman, at the end of the nineteenth century. She came back with her husband in 1905, pregnant, and she gave birth to my great-grandmother. In 1925, when she was dying, my great-grandmother gave something to my grandmother, who was a five year old girl at the time – a coral bead necklace, bought in States. I have it, because my grandmother gave it to me. Small corals, old, pale red. I was thinking about this yesterday and today. I have a lot of things from those women: the necklace, recipes, many stories, some songs and many embroidered tablecloths made by my grandmother and great-grandmother. I also have the impression that they are a little bit here, among living people. Unfortunately, I cannot explain how this is possible. I don’t know. But I’m working in this museum because of them, for sure. In the process of thinking about your project, I’ve realised this. So thank you! All of these things that I’ve been thinking about are full of yesterday’s light—I look forward to your project very much.

All the best for you,

Magdalena

For more of Aaron’s work, click here.

For other Ideas Series articles, please click here.