The Hackney Flashers Collective came into being in 1974, when Hackney Trades Council saw the need for an exhibition covering women’s role in the local labour force – to make up for the all too obvious shortfall in its planned celebration of ‘75 Years of Brotherhood’.

This piece has been republished for Photography+ #9 Alternative Narratives

They approached some women photographers who formed a group, and the result was Women and Work. It addressed issues of low wages and unequal pay, documenting women workers in factories that have since closed down (they made clothes and toys), as well as jobs that women still do today: as cleaners, hospital staff, dinner ladies and much else. Women and Work went on to do years of solid agitprop service at trade union conferences and Women’s Movement events.

Collectives burgeoned in the 70s. In their forms and functioning they varied, but they shared a general principle of cooperation rather than competition, without hierarchy, without leaders, often aiming to share skills and expertise with a wider community. Among them were filmmakers and theatre groups, printers, artists and campaigners. Co-ops thrived too, from health food shops to magazines and book publishers. These were the offspring of the 60s, emerging from the anti-war movement and the international ferment of the New Left. Some arose directly from the nascent women’s movement: the London Women’s Film Co-Op, the Sheffield Film Co-op, the See Red Women’s Workshop, Spare Rib magazine. In the Hackney Flashers, decisions were reached either by consensus or majority vote. Debate and disagreement were inherent in the process. We took this for granted, just as we assumed that the space for such alternative modes of work and activism would continue to grow and influence many more areas of life.

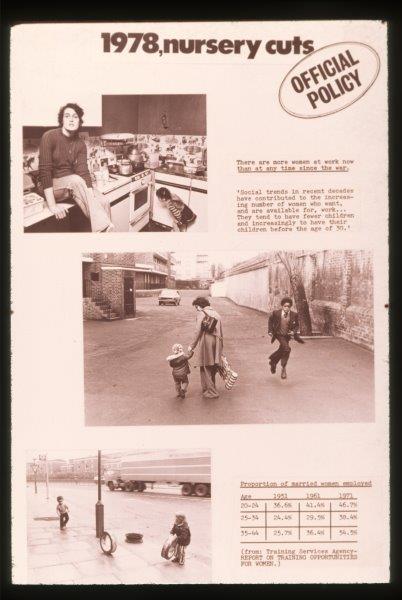

While the collective was photographer-based, from the outset it included a graphic designer and a cartoonist. I joined in 1976, when I was starting out as a freelance journalist. The Flashers had a second project in mind, on childcare provision and the lack of it. How to explore the effects on both parents and children? This impelled questions of visual representation: how do you delineate an absence, how do you clarify the structural difficulties of combining paid work with looking after children? The outcome was Who’s Holding the Baby? (1978)

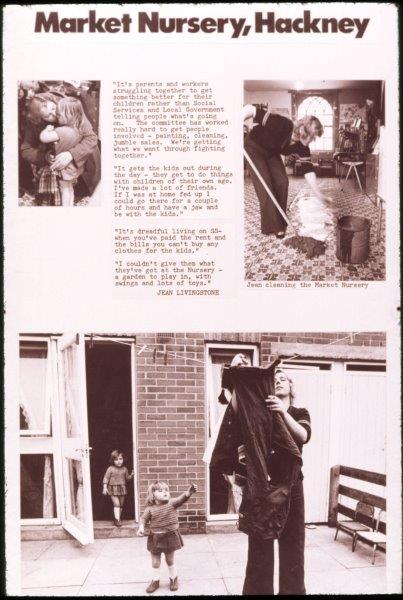

The core of the exhibition was a series of documentary pictures and interviews done over an 18-month period with parents and workers at the Market Nursery near London Fields; a community nursery, which meant that parents were involved in its management and played a part in day-to-day childcare there. Childcare was our focus, but jobs, incomes and housing inevitably entered the conversation too.

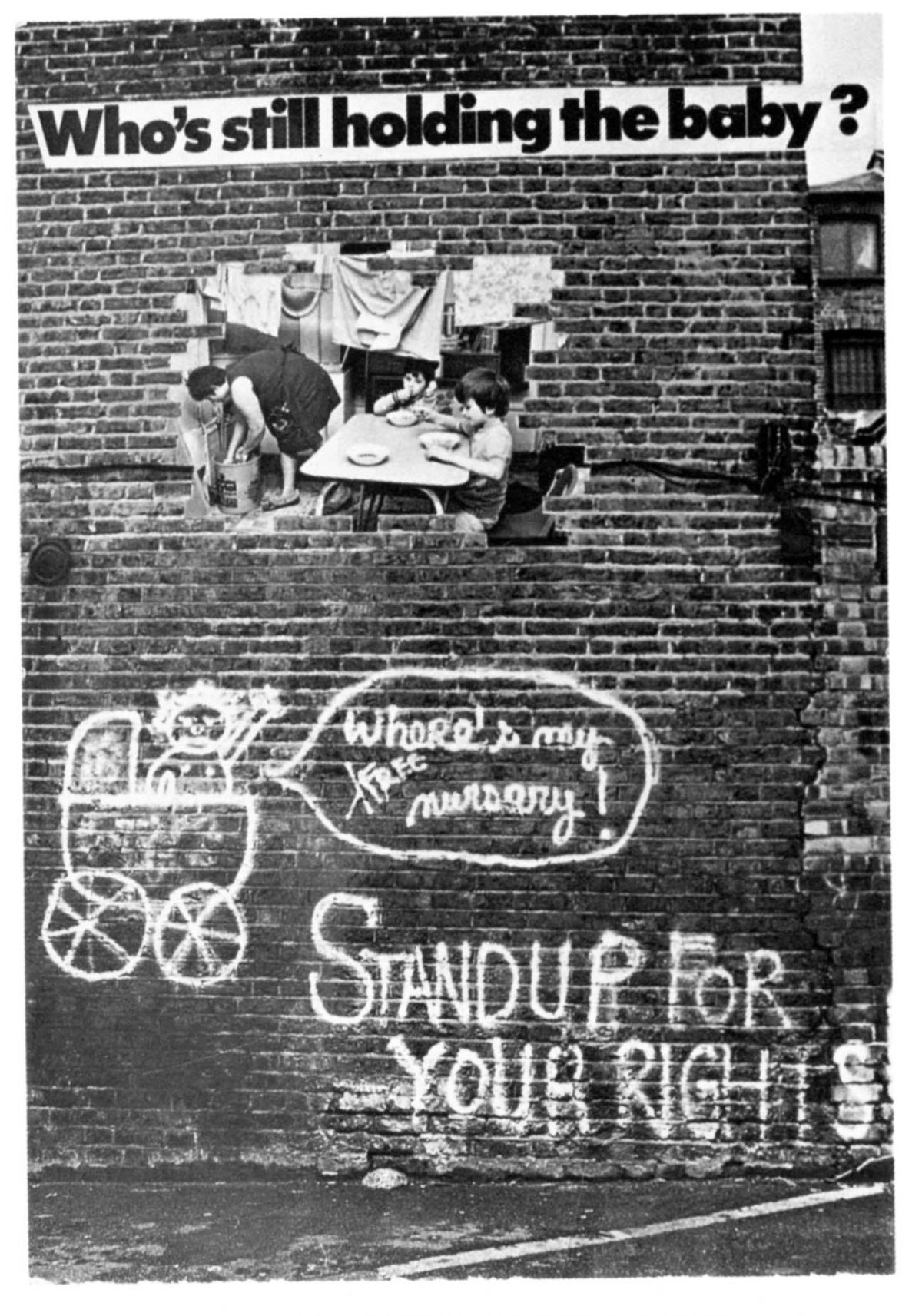

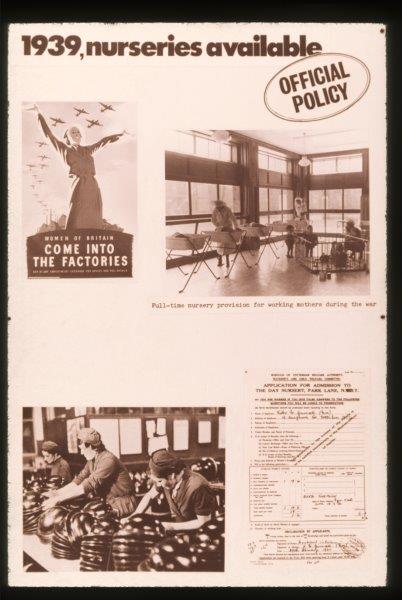

Women and Work had tinkered with photomontage, confronting stereotypes of women in magazines. Otherwise it followed the standard pairing of photographs and explanatory captions, with statistics to set women’s employment in context. Who’s Holding the Baby? departed from this conventional approach. It juxtaposed and collaged images, used archive material and original cartoons, and even contributed to the graffitiscape, inscribing a Dalston wall with a spraycan protest that was then photographed and deployed in a photomontage.

The result was a sequence of panels, designed for portability and touring, and with one copy left in other hands when the group dissolved. You can see most of them on the website of the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid. They are part of its permanent collection and got there unbeknownst to us. Subsequently we’ve discovered that panels have strayed as far as Canada.

We have found ourselves described on the internet as a feminist art collective. Perhaps this perception derives from the inclusion of Who’s Holding the Baby? in the Hayward Gallery 1979 show, Three Perspectives on Photography, an invitation we accepted only after lengthy discussion. Our intention was not to make art, but effective agitprop. The artist we consciously turned to for inspiration was the German communist John Heartfield, who used photomontage to attack Nazi ideology in the 1930s. Some of us knew the work of Hannah Höch from the Hayward’s 1978 exhibition Dada and Surealism Reviewed, and it wasn’t just cultural theorists who were reading Walter Benjamin’s Illuminations, which first came out in Britain in 1973.

Our collective history offers one example among many from the diverse network of feminisms that was the Women’s Liberation Movement in the 1970s. Who’s Holding the Baby? remains relevant at a time when childcare is more expensive than it has ever been, particularly in Britain, where it has become increasingly privatised.

Collectives are thin on the ground these days – thanks to the ideological and economic legacy of Thatcherism. But they aren’t all dead and buried. The current resurgence of feminism has seen young activists and academics eager to learn about the 70s, when solidarity was a keyword and we still had confidence in our power to challenge all forms of inequality.

–