By Iain Boal On September 11, 2001 Gary Schroen had just enrolled in the CIA’s ‘retirement transition program’. One week later, the former station chief in Kabul and Islamabad was on a plane to Afghanistan, leading a six-man assassination team in the hunt for Osama Bin Laden and his general staff.

In his memoir First In, Schroen recalled the orders he received from Cofer Black, the CIA’s head of counter-terrorism: ‘Capture Bin Laden, kill him and bring his head back in a box on dry ice.’ As for Bin Laden’s associates, Cofer said, ‘I want their heads on pikes’.

Schroen remembers his reply to Cofer: ‘Sir, those are the clearest orders I have ever received. I can certainly make pikes out in the field but I don’t know what I’ll do about dry ice to bring the head back – but we’ll manage something.’

Not much, as it turned out. No dry ice, no pikes. He returned home empty-handed to the company’s retirement program. Apparently he retained his faith in the agency, since in 2005 he confessed surprise that the CIA had still not managed to track Bin Laden down after nearly four years. The hunt, which had begun years earlier in the Clinton presidency, apparently ended this May in the old garrison town of Abbotabad in Pakistan. Apparently, that is to say, because seriously conflicting accounts of what happened on the night of May 2nd immediately began to emanate from both official and off-the-record sources following the commando raid on the compound in Abbottabad.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

In addition, the Pentagon refused to release any official photographs that would credibly establish the al Qaeda chief as having been among those killed in the attack. The result was hardly surprising, since the nature of today’s media abhors an image vacuum. Editors under pressure certainly had footage and photos of Bin Laden while alive but that was hardly the point of this story. Quite predictably, photographs from unofficial sources – supposedly of the dead Bin Laden – showed up in newspaper stories around the world, and began to circulate immediately in the infosphere.

Whether authentication was going to be an issue would depend on the outcome of George W. Bush’s bulletin from the wild West frontier: ‘Bin Laden: Wanted, Dead or Alive’. Capturing Bin Laden alive would have its own problems; the fiasco of Saddam Hussein’s trial and execution was testament to that. Bin Laden’s corpse would inevitably present a different set of issues.

Verification has two faces. On the one side, there is the internal matter of the commandos having to satisfy their officers that the job has been done, that they have got the right man. On the other, there is the PR problem for the state managers who have signed off on the assassination, and not just because it’s hard to trust a photograph these days. Although the CIA had long been in the assassination business—Patrice Lumumba and Fidel Castro are two notorious names once on a CIA hit list—the state-sanctioned murder of foreign enemies was (officially) proscribed following the crisis of legitimacy brought on by the defeat in Vietnam and the Watergate scandal at home. At least in the sense that McNamara and co, however concerned they became about the media reception domestically, paid little or no heed to the circulation of images among the population of Vietnam or the Third World in general. In March 1975, President Ford announced at a press conference, ‘I will not condone—in fact I condemn—any CIA involvement in any assassination planning or action… I am personally looking at, analyzing all of the more recent charges of any assassination attempts by the CIA or actual assassinations from its inception to the present.’ In early 1976, he issued an executive order banning assassinations, following the Church Commission’s recommendations. Church remarked that it was ‘simply intolerable that any agency of the government of the United States may engage in murder.’

Normal service was resumed in the 1990s under President Clinton. According to Richard Clarke, one of the president’s advisors: ‘He broke a 25-year tradition and agreed that there should be a hit list. The United States government should sponsor the assassination of terrorists.’ Clinton favoured the use of cruise missiles, but that carried with it the risk of collateral damage and related difficulties. Large explosions are also likely to obliterate the target and destroy the evidence needed for different reasons by the high command and the media mills. Pictures of large craters or piles of rubble may be compelling evidence of the ability of the US military to deliver terror from the air but who ever doubted that?

Nevertheless, on Clinton’s orders the US stationed two nuclear submarines off the Pakistani coast ready to launch cruise missiles if the most wanted enemy was located. Michael Scheuer, head of the CIA Bin Laden unit, has claimed that before September 11, 2001, the ‘intelligence was sometimes good enough to fire’. Just before Christmas 1998, Bin Laden was known to be staying overnight in a room in the governor’s palace in Kandahar. ‘We knew he was there’, Scheuer said, ‘because we saw him go into the room, and we know which wing of the palace, which room he was in…and the president and his advisers decided that ‘Well, if we kill him, some of the shrapnel might hit a mosque that was about 300 metres away’.’

After September 11 the full panoply of state violence was mobilised, from blitzkreig (including discussion of earth-penetrating nuclear bunker busters) to small-team special operations (‘to take the head off the snake’), urged on by the political commentariat of a nation in shock that had never before suffered aerial bombardment of its mainland. Lance Morrow, in a special edition of Time published in the wake of the attacks, fulminated, ‘Let America explore the rich reciprocal qualities of the fatwa…What’s needed is a sort of unified, unifying Pearl Harbour sort of purple American fury.’

The purple fury was exemplified by Cofer Black’s intemperate order—‘heads on pikes’—which was however quite consistent with the strange amalgam of the newfangled and the atavistic that has characterized American statecraft since 2001. Black now claims that the order demanding Bin Laden’s decapitation was issued to aid identification. ‘You have to have a compelling proof that you’ve been successful and it can’t be, ‘Well it looked like him’.’ Although Obama’s White House maintains that had Bin Laden immediately surrendered he could have been taken alive, that view is contradicted by one special operations officer who told a freelance journalist: ‘There was never any question of detaining or capturing him—it wasn’t a split-second decision. No one wanted detainees.’ Shades of Guantanamo.

In the event, according to the same freelancer’s account, ‘A pair of SEALs unloaded the body bag and unzipped it so that McRaven [who was in command of Joint Special Operations] and the CIA officer could see Bin Laden’s corpse with their own eyes. Photographs were taken of Bin Laden’s face and then of his outstretched body. Bin Laden was believed to be about six feet four, but no one had a tape measure to confirm the body’s length. So one SEAL, who was six feet tall, lay beside the corpse: it measured roughly four inches longer than the American. Minutes later, McRaven appeared on the teleconference screen in the Situation Room and confirmed that Bin Laden’s body was in the bag…All along, the SEALs had planned to dump Bin Laden’s corpse into the sea—a blunt way of ending the Bin Laden myth.’

At any rate that is one version of what happened, as published in an August 2011 New Yorker piece by Nicholas Schmidle. The world of spooks and special ops is of course a hall of mirrors, an echo chamber of disinformation, and very conflicting accounts began to come out of the Pentagon, Langley and the White House in the hours and days after the attack. The Schmidle account supposedly pierced through the fog of war to tell the inside story of Operation Neptune’s Spear, and the final hunting down of “Crankshaft”. The hardware used by the assassination squad is described in pornographic detail and small arms brand names given fetishistic attention – Ian Fleming meets the History Channel. All presumably intended to suggest an I-was-there authenticity: one of the assassins, for example, was wearing ‘a shirt and trousers in Desert Digital Camouflage, and carried a silenced Sig Sauer P226 pistol, along with extra ammunition; a CamelBak, for hydration; and gel shots, for endurance. He held a short-barrel, silenced M4 rifle. (Other SEALs had chosen the Heckler & Koch MP7.)’

In fact the reporter, Nicholas Schmidle, never spoke to any of those on the mission, and turns out to be the son of a general in Special Operations who is currently the Deputy Chief of US Cyber Command. All accounts, including Schmidle’s, should therefore be taken with a pinch of salt. Nevertheless, the statements coming from various sources within the state apparatus—including the wishful thinking of a SEAL officer, ‘I’m sort of glad we left the helicopter there. It quiets the conspiracy mongers out there and instantly lends credibility. You believe everything else instantly, because there’s a helicopter sitting there’—all speak not just to the intrinsic nature of such operations, always on the brink of chaos, or to the bungling and incompetence at the PR end of things, but to a much deeper set of problems facing the superintendents of empire. They have found themselves increasingly drawn into micromanaging the means of symbolic production, as well as the business of enforcement.

The state, in other words, has become enmeshed in new modes of representation and mediation—in particular the internet and the global reach of al Jazeera—that have developed since the end of the last major conflict in which the US was involved, the war in Indochina. The defeat in Vietnam was not experienced by the Pentagon or the State Department as a failure of mastery in the realm of representation.

Al Qaeda was quite a different foe, because it grasped an essential fact about modern states, that they live more and more in and through the image. Historically, the terrorism of states and their enemies circulated—was intended to circulate—in the form of rumour rather than image. Terror performed its work, in other words, through hearsay and panic and fear. September 11th was different. It was designed above all to be visible, to circulate as image. (Not that there wasn’t a precedent; more than half the world’s motion picture film stock was used to record the mushroom clouds rising from the Able and Baker thermonuclear explosions in the Pacific.)

No assassin, no propagandist of the deed, ever matched the impact of the aviators who struck the World Trade Center in 2001. The event signalled the arrival in the heartland of global capital of a new model vanguard, managing a coup de théâtre combining two of the key apparatus of modernity – the airplane and the camera. First, Atta and his crews turned the planes back into their original function as vehicles of the weapons of mass destruction. Secondly, even in its rejection of the West, the Islamic vanguard displayed a grasp of the virtual within modernity, and especially the new technics of reproduction and dissemination – and the possibilities of the camera, the video clip and the internet.

The US imperium suffered a defeat on September 11 at the level of spectacle, and ever since has been trying to frame a reply, by means of the same symbolic apparatus, that would be commensurate with the destruction of the Twin Towers. And inevitably failing.

For a decade the state propagandists have been lurching from bathos to fiasco. In the case of Saddam, from rent-a-crowd statue-toppling in Baghdad (a transparently stage-managed parody of iconoclasm) to trial by tongue depressor and on to an absurdist execution scene. The frustration of Bush’s Secretary of Defence at this state of affairs was evident in a notorious rant delivered to the Council on Foreign Relations. ‘Our federal government is really only beginning to adapt our operations to the 21st century. For the most part, the U.S. government still functions as a five and dime store in an eBay world. Today we’re engaged in the first war in history—unconventional and irregular as it may be—in an era of e-mails, blogs, cell phones, Blackberrys, instant messaging, digital cameras, a global Internet with no inhibitions, hand-held video-cameras, talk radio, 24-hour news broadcasts, satellite television. There’s never been a war fought in this environment before.’

Osama Bin Laden’s chief lieutenant Ayman al-Zawahiri revealed himself to be on the same wavelength: ‘More than half of this battle is taking place in the battlefield of the media.’ Rumsfeld in turn recognised that his opponent understood the new landscape, and commented that al-Zawahiri was not ’some modern-day image consultant in a public relations firm here in New York City…Consider that the violent extremists have established media relations committees – these are terrorists and they have media relations committees that meet and talk about strategy, not with bullets but with words…They plan and design their headline-grabbing attacks using every means of communication to intimidate and break the collective will of free people.’

Rumsfeld’s prescription, though technocratic and worthy of the most banal mediologist, recognised the common terrain: ‘The longer it takes to put a strategic communication framework in place, the more we can be certain that the vacuum will be filled by the enemy…The U.S. government will have to develop an institutional capability to anticipate and act within the [current globalised] news cycle. That will require instituting 24-hour press operation centers, elevating internet operations and other channels of communication to equal status with traditional 20th century press relations.’

It’s not clear that the image managers are doing any better under Obama than they did under Bush. The decision to kill Bin Laden created a martyrdom problem; the decision to mitigate the martyrdom problem by dumping the body at sea created a verification problem; the decision not to release the photographs of the corpse (to deal with the image-of-the-martyr problem) or of the climax of Operation Neptune’s Spear created a vacuum leaving the field open to photoshoppers, truthists and anyone at or near the scene with a phone camera.

Just to address, for the moment, the question of verification and the authenticity of photographic images. This is not a trivial problem, and far from a new one. Indeed it goes all the way back to the birth of the medium. Actually, for the pioneers of photography the doctoring of negatives was a routine matter. And for a variety of reasons – sometimes, to create an image that could be publishable as a book plate, by means of pastings and touch-ups; sometimes it was done simply for aesthetic reasons, since ‘light-writing’ was seen as a kind of first draft; sometimes, for practical reasons having to do with the technical state of the craft. For example, Muybridge and Watkins, in making their great landscape photographs, would often cobble together two separate negatives of sky and foreground, each with different exposures, because wet plate technology using collodion on glass produced overexposed and bleached skies.

These manipulations and technical fudgings were, you might say, ‘innocent’ artifacts of the mid-Victorian limitations of plate sensitivity and shutter technology. On the other hand, they certainly were problematic in the case of the famous photographs taken by Muybridge and commissioned by the railway baron and horse breeder Leland Stanford. Muybridge was employed specifically to achieve images that would adjudicate whether all four legs of a trotting horse were ever in the air at the same time, using the camera as scientific arbiter of truth. The early results were desperately ambiguous, and of course photography’s relation to ‘the real’ remains a profoundly vexed question. Not to say often absurd: consult Alain Jaubert’s Le Commissariat aux Archives: Les Photos qui Falsifient L’Histoire for hilarious examples of ‘before and after’ photographs of those being airbrushed from history.

The role of photography in the history of propaganda, though at times ludicrous, raises complex and serious questions. Presumably the reason why the new ubiquity of the phone-camera – facilitating photography from below, subveillance as it were—is proving awkward for the powerful is because there is something to the idea of the camera as a truth machine.

On this topic the photographic historian Steve Edwards has some interesting reflections at the conclusion of his Very Short Introduction to Photography. The technology has now reached the point where the fundamental features that made an image photographic, namely, traces of light captured by a receptive substance on a film plane, may be lost. This is the danger—or the promise—implicit in full-bore digitization. Edwards advises against panic at the prospect, and quotes Allan Sekula on the matter: the ‘old myth that photographs tell the truth has succumbed to the new myth that they don’t’.

Since the photographic evidence attesting to the truth of Bin Laden’s death is being withheld, its veracity is moot. (Which raises an interesting topic: why did no one challenge the photographs from Abu Ghraib?) Most of the surrogate images of the assassinated Bin Laden—dragged and dropped in to fill the lacuna—were obviously faked or photoshopped.

The photograph of the bed and the blood-stained carpet does, on the other hand, have an authentic feel. Its quality suggests that it was taken by a camera phone. But what exactly is it evidence of? Clearly something gory. And familiar enough from endless CSI reruns. But if CSI is the point of reference here, then that makes the Abbottabad compound more a crime scene than a war zone. And if so, then whose crime? And indeed, what crime? The transgressing of national sovereignty and the rules of international law?

As for the photographs that have been officially released, contradictions abound. The shot of Osama alone and watching a monitor is intended presumably to locate him in the Abbottabad compound. He is sitting on a couch in his “entertainment centre”, with a beanie on his head and a remote control in his hand. The image deflates and diminishes its subject; it is presumably meant to do so.

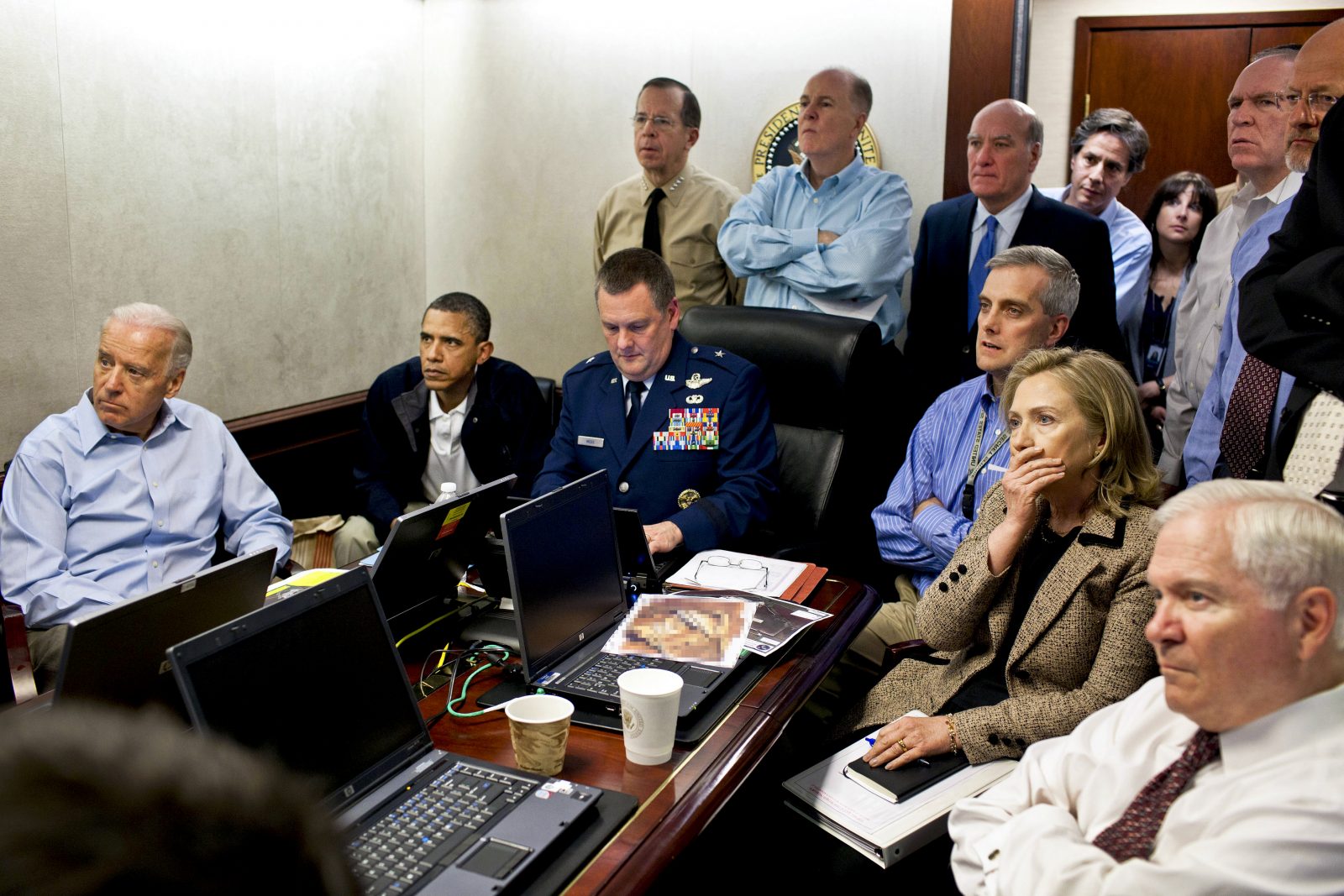

It represents a kind of humiliation. But, if so, then what is its relationship to—in what ways does it speak to—the photograph released by the White House of Obama watching TV with friends in the Situation Room? We are not allowed to see what Obama’s team are seeing. Someone in the room later described it – ‘like watching the climax of a movie’. But when Americans are shown clustered round a domestic TV, it means usually one thing: they are watching sport. Obama’s posture combines the tension of the baseball fan and the passivity of the spectator. In the society of the spectacle should we be surprised that the two most widely circulated images surrounding Operation Neptune’s Spear are pictures of people watching TV. Or that the ‘situation’ the group is absorbed in what appears to be some kind of game?

The management of Neptune’s Spear fell short, no doubt, of Rumsfeld’s vision for the ideal state media apparatus, a vision at one with the system of private power that he served. A system in which human activities and products are valued insofar as they participate, as abstractions or phantoms, in a circuit of exchange. The spectacle is a theory of the ongoing consequences of that ghost-dance for the day-to-day substance of human interactions and self-understanding, and the specific political problems and opportunities that follow as materiality cedes to appearance.

The assassination of Bin Laden, years after his kill-by date, was intended to close a chapter in the U.S. state’s response to the spectacular defeat of September 11. Yet the sense of bathos that lingers in the (image) memory of Saddam Hussein in captivity clings also to the photos vouchsafed us of Operation Neptune’s Spear and the killing of “Crankshaft”. The state was forced to try to manufacture per impossibile an adequate response to the events of that day in 2001, and it terminated in anti-climax in the foothills of the Hindu Kush. Nothing, of course, in the realm of spectacle, could conceivably match the horrendous perfection of that image of capitalism’s negation. Negation not once, but a second time, ensuring that thousands of cameras would be recording the dreadful scene. No bulletin was issued, no explanation was needed.

The state has had no option but to respond on the terrain of the image precisely because the spectacle is not merely a network of images but a fabric of social control, incorporating the image world, certainly, but not constituted by that world.

The old Secretary of Defence’s plea for a communications upgrade was an indication of the anxiety induced by an—albeit vulgar and half-baked—understanding of what is at stake, and knowing that control of the image world is far from secure. The contradictions of an increasingly ‘wired’ world have since been revealed by the operations of Julian Assange and wikiLeaks. One may agree that the new technics have redrawn politics and journalism, while remaining dubious about the ability of any particular photoshop of horrors or data-dump to inflict permanent damage upon either Empire or Jihad. At least while the spectacle reigns. As to what might be involved in image-making against the spectacle, that is an urgent and difficult question, and one not for photographers only.[/ms-protect-content]

–

Published in Photoworks Issue 17, 2011

Commissioned by Photoworks