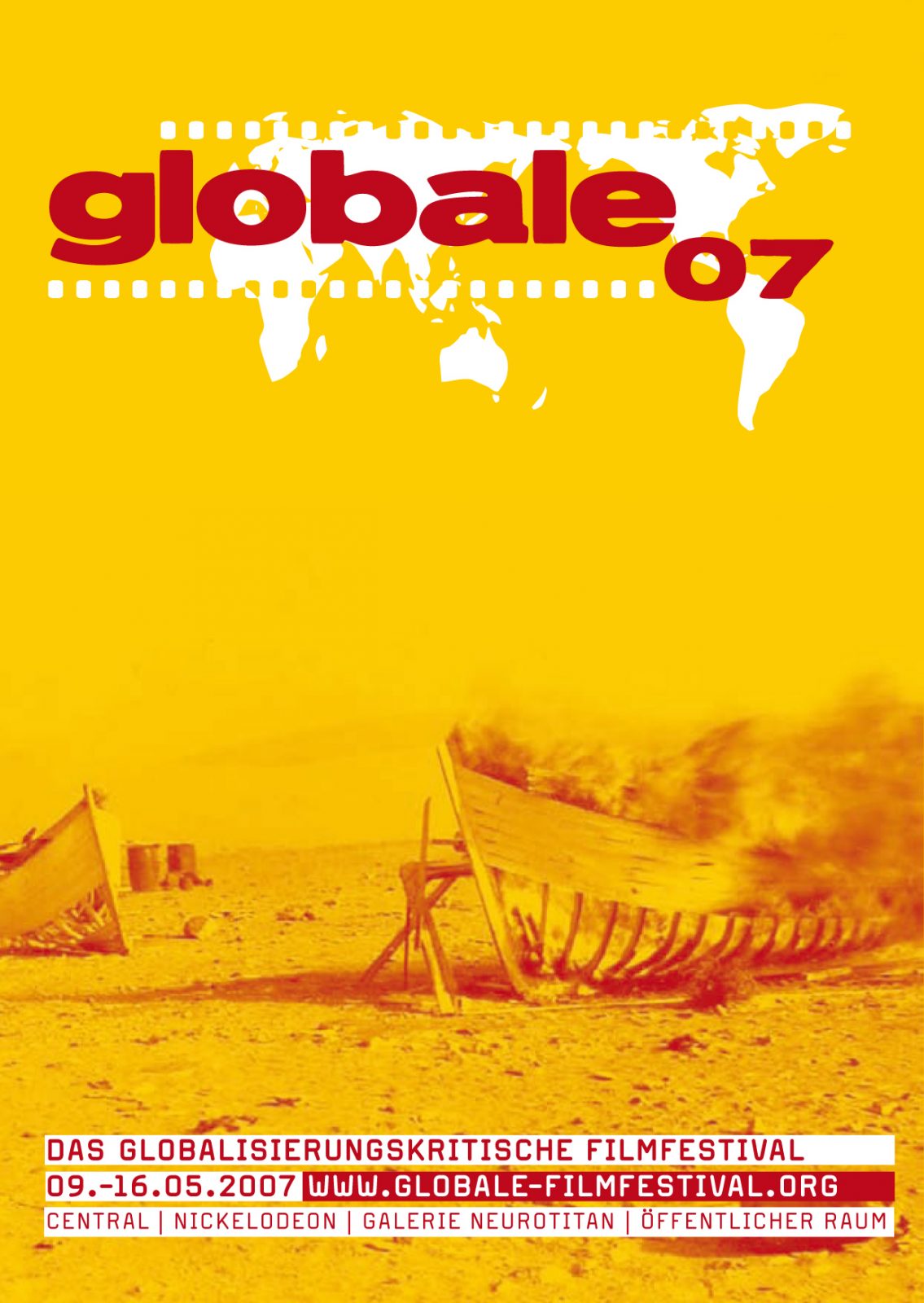

I provided the image in the poster for the 2007 Globale film festival in Berlin. It depicts burning boats, initially built by illegalised migrants hoping to reach the Canary Islands before being destroyed by the Moroccan police once they had captured them.

The photograph was initially shot by the Moroccan police in the southern Moroccan desert. It was handed to Ursula Biemann and myself by the police while we were filming towards video projects on illegalised transit migrants in Morocco.

I chose this image to illustrate my video because it seemed to condense the entire condition of transit migrants in Morocco. Tangled together in it are the self-organised networks of migrants spanning the whole Maghreb and the constantly expanding European border regime, which subcontracts the repression of migration to the States of the Maghreb. Until 2004, migrants rented the services of fishermen along the coast, but with the fishermen’s barks coming under increasing control, migrants were forced to have recourse to the services of smugglers and to build their own barks in the desert. The Moroccan police and military deployed ever more resources to patrol the desert in jeeps and helicopters. Illegalised migrants remained trapped between sea and desert. This violent clash between the logic of migrants and that of their control finds its echo in this image, in the opposed elements of fire and water. The image attains an almost universal meaning: the boat, the vehicle which is meant to bring them to the Promised Land, is destroyed, and with it their hopes for a better life.

This image points powerfully to a dire social and political reality. But, as it has been used in particular instances, it has also failed to point to itself, to indicate its own conditions of production and circulation. Although the information accompanying the image always indicated that it was originally made by the Moroccan police, the focus was always on the ‘photographed event’ – the destruction of migrants boats by the Moroccan authorities, not on the ‘event of photography’.3 In using it myself I did not ask: what exactly is the role of the act of photography and the circulation of this image within the violent containment it documents? It is this question that I would like to address here, by paying closer attention to its conditions of production and circulation, and to the materiality of the photograph.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

The image of burning boats was handed to us by the Laayoune police in Southern Morocco, on a CD that contained over 100 such images. Taken both from the air and from the ground, they clearly illustrate the systematic tracking down and capture of migrants, the destruction of their belongings and, most of all, the boats they were building.

On one of these images, one can distinguish the shadow of the photographer. Although it does not disclose much about his identity, it is almost certain that he is a policeman. The systematic character of the documentation provided by the CD full of images leads us to think that the photographer is accompanying several operations. Furthermore—according to Hicham Rachidi of the Moroccan anti-racist organisation GADEM—since 2004-5, raids performed throughout the country were frequently photographed or filmed by the police and military. The camera, then, had become one more weapon in their arsenal. But another element in this image points significantly to its conditions of production and circulation: it bears a white frame of thin white angles. The image of the burning boats that I have so often used also had a frame of this sort, but these were always cropped out for publication. What are they?

This image clarifies beyond doubt the answer to this question. In addition to a thin frame that is visible as the angled black areas bordering the image, it bears a binding. This establishes that the photographs of barks burning on our CD were scanned from their printed-arranged-classified-for-display format. The 100 images we were handed thus record the materiality of the photographs and their storage as much the photographed event. These thin white or black frames and the binding point towards the images’ status as an object: their being-in-the-world. But how, precisely, were these image-objects inserted into the world by the police?

The pictures were certainly used as illustrations and as evidence in their reports (which they handed us the front page of). Clearly, they were used as handouts for curious journalists—or for artists like us—if the police was unable to provide the live event of a boat-bonfire on the Moroccan beach. But why would the Moroccan police need to document the capture of migrants and the destruction of their barks so systematically? And why would they be so willing to publicise what appears to us to be evidence of violent repression?

My interpretation is that, for the Moroccan police, these images are evidence of a job well done. They are evidence, directed to its own population, that the Moroccan state is capable of managing the flow of people across its borders, one of the main attributes of sovereignty. They are also directed to Morocco’s powerful European counterparts, under pressure from whom the Moroccan authorities perform their duty and from whom they receive significant funding.

In this case we need to ask the question: does the image simply document the event of violation, or is the event, to a certain extent, produced for the camera, with an eye on the future circulation of the image? I believe the latter. If it is not the act of photography that sets the migrants boats ablaze before deporting them, then the practice of the image has a distinct agency in shaping these events. The Moroccan police needs less to do, than to show that it is doing.

Finally, we can ask whether, in using these images did I not, despite myself, risk complicity with these objectives? In presenting them once again, here, am I doomed to perpetuate the spectacle of Morocco’s labour as a watchdog for the European Union? A tentative answer might be as follows: I believe it is necessary to convey the political meaning and the social reality that the images represent by reframing these within a critical discourse on migration and migration management, but also to attend to the power relations involved in the production and dissemination of the images themselves. To do this one must shift from focusing on them as images of migration to following carefully their migration as images, including the changes in format and material qualities they undergo each time they pass hands – or computers. Only then may we hope to escape the reproduction of the spectacle of power.

[/ms-protect-content]