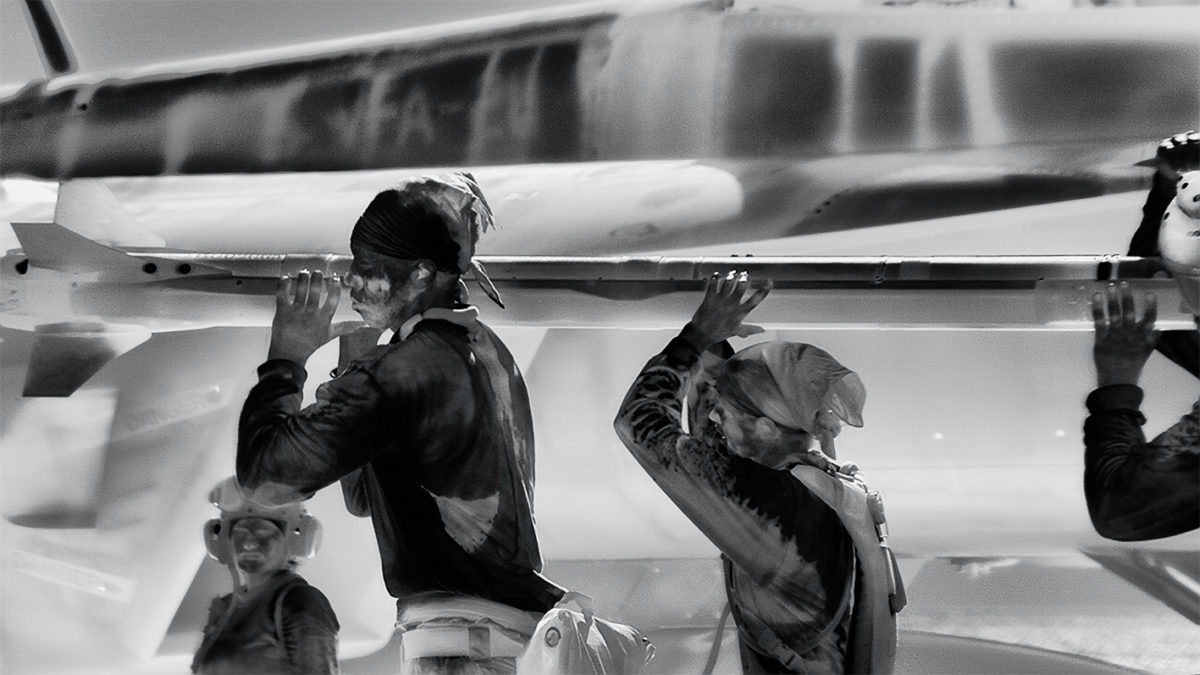

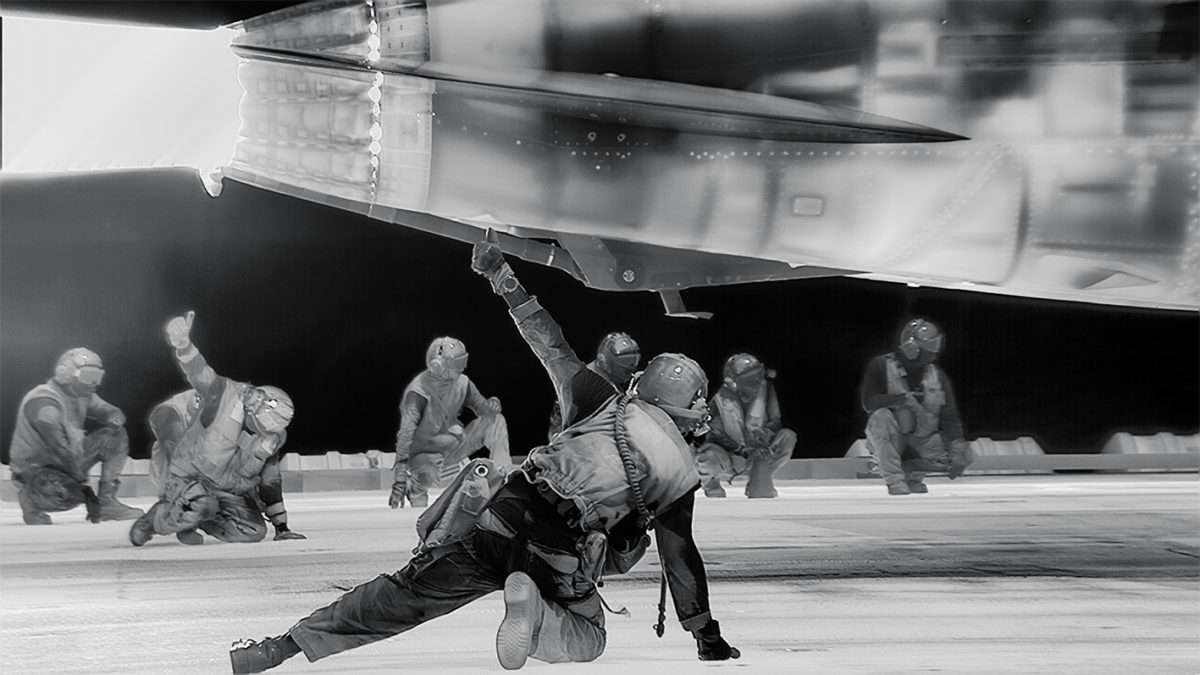

Richard Mosse talks about his latest project, Incoming, which uses a weapons-grade camera to photograph refugees and migrants as they journey across the Middle East, North Africa and Europe.

Photoworks: There is the spectre of violence in using this weapons-grade camera to photograph refugees and migrants, unknowingly and from a distance, as they make their journey to safety. Can you tell me how you approached the ethics of this work while shooting and afterwards, when presenting the work?

Richard Mosse: There is the spectre of violence in all forms of photography, not simply within the echo of the word shooting, but in the history of photography too, most of which has evolved directly out of military research. That’s especially the case with the technology that I chose to work with to make Incoming, which is not generally available for consumer or professional use, and has been developed and produced by a multinational defence and security company that also produces cruise missiles, drones and other technologies. This is a work about the refugee crisis which was made with a military tool designed specifically for battlefield awareness and extreme long range threat detection and border surveillance at a moment in history when, for example, Frauke Petry, the chairwoman of the German extreme-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD), has said that police should shoot migrants at the borders, trying to enter their country illegally. Imaging the refugee crisis in such a way may feel unethical – discomfiting or upsetting the viewer – but it is not. Indeed, that feeling of ethical violation has the potential to activate the viewer, to push them into a space where they are no longer simply consuming imagery, but where they are consciously and cautiously engaging with the work and its meaning, while checking themselves, their baggage and reflexes. This is what art is all about, and what it does strongest. It is not a soapbox.

In spite of the camera’s initial ghostly dehumanization of the human body, we found that it offered us a very powerful tool to communicate the painful journeys of refugees, in new and unfamiliar ways that are often tender, intimate or vulnerable. We wanted to use this military surveillance tool against itself to create an immersive, humanist art form, allowing the viewer to meditate on the profoundly difficult and frequently tragic journeys of refugees through the metaphors of hypothermia, global warming, border enforcement, mortality and what the philosopher Giorgio Agamben has called the ‘bare life’ of stateless people.

a book of still frames derived from Incoming, 2015–2016 – a three screen video installation by Richard Mosse in collaboration with Trevor Tweeten and Ben Frost. Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Almost all the scenes in the film were shot in public spaces, except the scene in the former Tempelhof Airport hangar which has been converted into an emergency refugee shelter. In this case, we put up posters within the space a few days prior to our filming, advertising our project, and the scheduled times of filming, explaining that it is a work of art made with a thermal camera that anonymizes its subject, so that anyone concerned about being identified within the film would have nothing to worry about. There were other scenes too harrowing to include in the film, such as the scene in which a young drowning and hypothermic refugee girl, a victim of a disaster at sea, is picked up by her heels and hung upside down while emergency workers slap her back to try to release water from her lungs. You can hear this audio, but we chose not to include the visuals as they were too graphic. Instead we cut about twenty seconds of black (no visuals at all) immersing the viewer in darkness to allow them to focus on the disturbing sound track. The camera, on the other hand, often translated overly graphic material into much less disturbing footage, such as the footage shot of the pathologists on the island of Rhodes extracting DNA from the corpse of an eleven year old girl who had drowned off the island of Leros. Such a scene would be far too graphic for exhibition had it been filmed with a conventional camera, but filmed with the thermal camera, it seemed prosaic, procedural and routine. So, our approach with the camera and the resulting footage was being constantly reviewed and discussed between us, and treated with great prudence.

a book of still frames derived from Incoming, 2015–2016 – a three screen video installation by Richard Mosse in collaboration with Trevor Tweeten and Ben Frost. Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

PW: The sea has always played a role in the history of migration and the movement of people and goods. It can be a means of escape or of disaster. Can you talk about the role of the sea in your work in displacing and disrupting people’s lives?

RM: Attentive viewers will notice that many of the scenes in Incoming were actually shot at sea. I think about two thirds of the film was shot at sea or on ships. Other parts of the film were shot in the Sahara Desert, which Libyans call the Second Sea. I guess these are all places that don’t have sovereign law, where non-citizens and citizens have equality, where the figure of the dispossessed refugee does not provoke a state of exception, because there is no nation state to speak of. Aboard the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt, forward deployed in the Persian Gulf to bomb IS positions in Iraq and Syria, the commander liked to remind us that the deck of the boat is “four acres of sovereign US territory.” He was wrong. It is actually four acres of dangerous metal floating in international waters.

Curiously, one of the main motifs of my previous work, The Enclave, was also water. Not the sea per se, but lake water, rivers and streams, and Mai Mai militias. (Mai means water in Swahili.)

PW: How did impartiality influence your approach to making Incoming and how, if at all, did this change over the 2 years?

RM: I really don’t think impartiality was a driving concern of ours — how could it be when we chose to foreground a very particular subjectivity through the choice of such an uncanny medium, one that is at once alien and yet familiar. Also, it isn’t that kind of classic documentary that takes a balanced, judicious approach and accounts for all sides, with a reassuring voiceover spoken in Queen’s English. It doesn’t try to explain anything, except the medium and how it was intended (and not intended) to image this subject. Indeed, the score and the edit push the viewer in certain directions emotively and viscerally, which can be by turns disorienting or surprising.

PW: Can you talk about the collaboration between yourself, composer Ben Frost and cinematographer Trevor Tweeten?

RM: It is the greatest, deepest, most powerful thing to be able to work so closely to represent these historic events with such close friends. Much greater than the sum of its parts, Incoming is the fruit of this collaboration, which has evolved for years now. (Trevor Tweeten I have worked with since 2008 and Ben Frost since 2012. Jerome Thelia since 2008.) It isn’t easy to build relationships like these. It is not just about producing, but also about supporting each other.

a book of still frames derived from Incoming, 2015–2016 – a three screen video installation by Richard Mosse in collaboration with Trevor Tweeten and Ben Frost. Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

PW: What did you learn from this project, in terms of the role of the camera in documenting and recording historic moments?

RM: I learned a great deal about the pain and struggle of so many, the enormous risk they have taken, leaving everything behind, saying goodbye to friends, family, homes, to risk everything, to survive. If the camera is simply a foil or conceit for us to be able to more deeply engage with that, then I suppose what I have learned about – in relation to the camera’s role – has to do with belief. We believed that the camera could reveal something for us, or help us reveal something, and that belief (rather than the camera itself) was what was really at stake.

See here for more of Richard’s work.