I was always entranced by the photographic image: what an image meant to me – what I imagined it meant to others – what it told us of a scene, a people, a life – and, by omission as much as inclusion, it often endorsed.

In my own work I can see how relatively quickly I moved from making series’ of still photographs, to incorporating text into my photographic projects, to making moving image work. I have always written scripts, poetry and fragmentary texts. In the last six months I have been part of an artist project Carte de Visite, which means I have finally confronted my discomfort at using ink, and my hands (other than as implements to push buttons), to create work that I feel excited about.

Really what it has meant is that I’ve been able to think about the photographic image and how it can be interrupted, its meaning dislocated and further constructed through the use of ink or paint and the hand – my hand. I have used two of my concepts, the audible fingerprint to think about how the voiceover and the scripting I make in film brings me into the piece of work – enabling me to act and play with the idea of authorship. The energized frame, (for me present in moving image), has enabled me to create an energy that I didn’t always find in my photographic work. But the idea of the hand making a mark on the image, around the image, across the image, alongside the image – even instead of the image has invited me to seek yet another way of working with images.

Clarissa Sligh first introduced me to the idea that photography had the potential to communicate with other ink based mediums – creating dialogues and visual punctuations. She used her hand to write, to draw and to obscure – pushing this relationship between text and image and drawing-based gestures. In Reading Dick and Jane with Me, 1989, she uses cyanotype processes alongside crude ink sketching and text. This juxtaposition develops a challenge and tension in the work, perhaps, revealing how culture maintains its place and position, replicating understandings, enabling a process of control and containment to persist.

The children’s reading series this piece refers to is now understood widely to be one that upheld the confines of gender but, also by its omissions, the accepted structural positions around race and class. Sligh reveals an agenda sometimes unseen, but especially poignant for all those eager children learning to read. The text is written across and around inserted photographic and drawn images that are perhaps defaced, perhaps subversively embellished. The children are not white middle class children but black African American children. As Sligh developed this work over a number of years we begin to see brighter colour and more emphatic interventions from her pen, and then the inclusion of the public who are invited to respond, onto the work, with their own hands. The drawing is simplistic and messy. The cyanotype process remains.

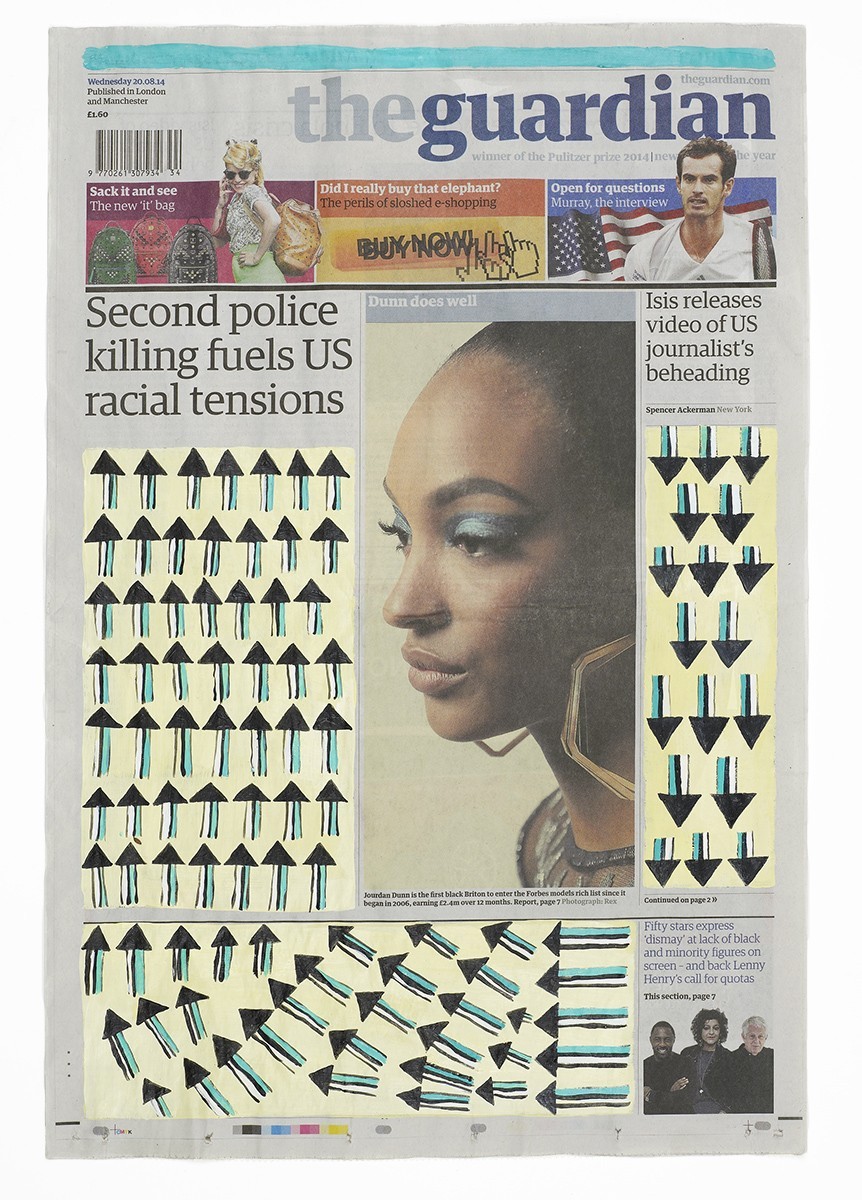

Earlier this year when I saw the series by artist Lubaina Himid called Negative Positives The Guardian Archive, I fell again into a state of troubled intoxication. Himid is an artist, she uses paint and is known for her painting. She is not a photographer and yet made a piece of work that explored the position and the behaviour of the photographic image, particularly but not exclusively around race and women – in this instance in the liberal bastion of newspaper journalism The Guardian.

This work makes sense of all those feelings of frustration, hurt and anger I have felt looking at advertisement billboards or watching TV adverts growing up. This project spans The Guardian papers from 1983 to 2015. Himid says she began her enquiry in 1983 because she wanted to interrogate her feeling that The Guardian had decided not to photographically represent black people – she says ‘wherever we looked we weren’t visible’. So her quest began, to find images of black people in her favourite newspaper. In her first year (1983) she found just one image – and it just so happened to be a ‘hideously constructed’ image of the opponent to Robert Mugabe.

When in 2007 Himid revisited the pages of The Guardian with scrutiny, she said that she had continued reading The Guardian and carried on collating her archive, feeling that although black people’s representation had increased, something new had begun to trouble and upset her. She began to explore and unpick what her reaction was about, She found the juxtaposition between language and image was now almost more aggressive than the absence of the earlier years. ‘Thieves, animals, venomous, despair’ jumped out on pages whenever black people were present – titles and content. These words undermined any positive connotation the image might have conveyed. She remembers a story focused on the unveiling of the plaque on a house in London where Bob Marley had stayed, jammed next to an explicit article highlighting the prison violence by black inmates in Wandsworth Prison; the negative story undermining the positive.

Himid began to intervene – painting out the negative story and text leaving the positive image or story in place to hold its presence on the page – to give it a chance to represent something positive at least. She used patterns and colours that she fancied, decorating the pages giving a backdrop to the photographic imagery.

The work I was so pulled in by was a piece made in 2015 that focused on Himid’s archive compiled between 2007- 2015. In this work, Himid has moved on from painting out what incites her, to accentuating the choice of juxtaposition demonstrated by either subconscious or clever editorial decisions in the pages of the paper.

So we have a repetition, replication, reinterpretation of imagery; that whilst obscuring some of what it is on the page, it accentuates that thoughtful or thoughtless (who knows) juxtaposition that Himid is concerned with. When I spoke with Himid about the project, I felt a keen sense of understanding because these were the very thoughts and feelings I had spent many years reconciling, questioning and arguing with people about.

The work speaks of something that slides underneath the surface, subliminal messages that reach us suggesting worth, achievement, value and potential based on race and gender. Messages that often we deny in a contemporary world of The Guardian reading and exhibition openings.

This is a cultural enquiry where paint/drawing/text does the work – interrupting and challenging us to really see what could be happening, on that page that we might read every day without noticing a thing.