We catch up with Prix Pictet 2017 nominee Mandy Barker, to hear more about her 'imperfectly known animals'.

Photoworks: Hi Mandy, can you tell us about the work that you’re showing in the Prix Pictet and how it responds to the theme of space?

Mandy Barker: The theme of my series relates to the vast ocean space of water that covers seventy per cent of the Earth’s surface. Water is the essential ingredient for any life-supporting world but which is now under threat from over 8 million tons of man-made plastic that enter the oceans each year.

The project highlights current scientific research which has found that plankton ingest micro plastic particles, mistaking them for food, and at the base of the food chain they are themselves a crucial source of food for many larger creatures. The potential impact on marine life and ultimately, man itself, is currently of vital concern.

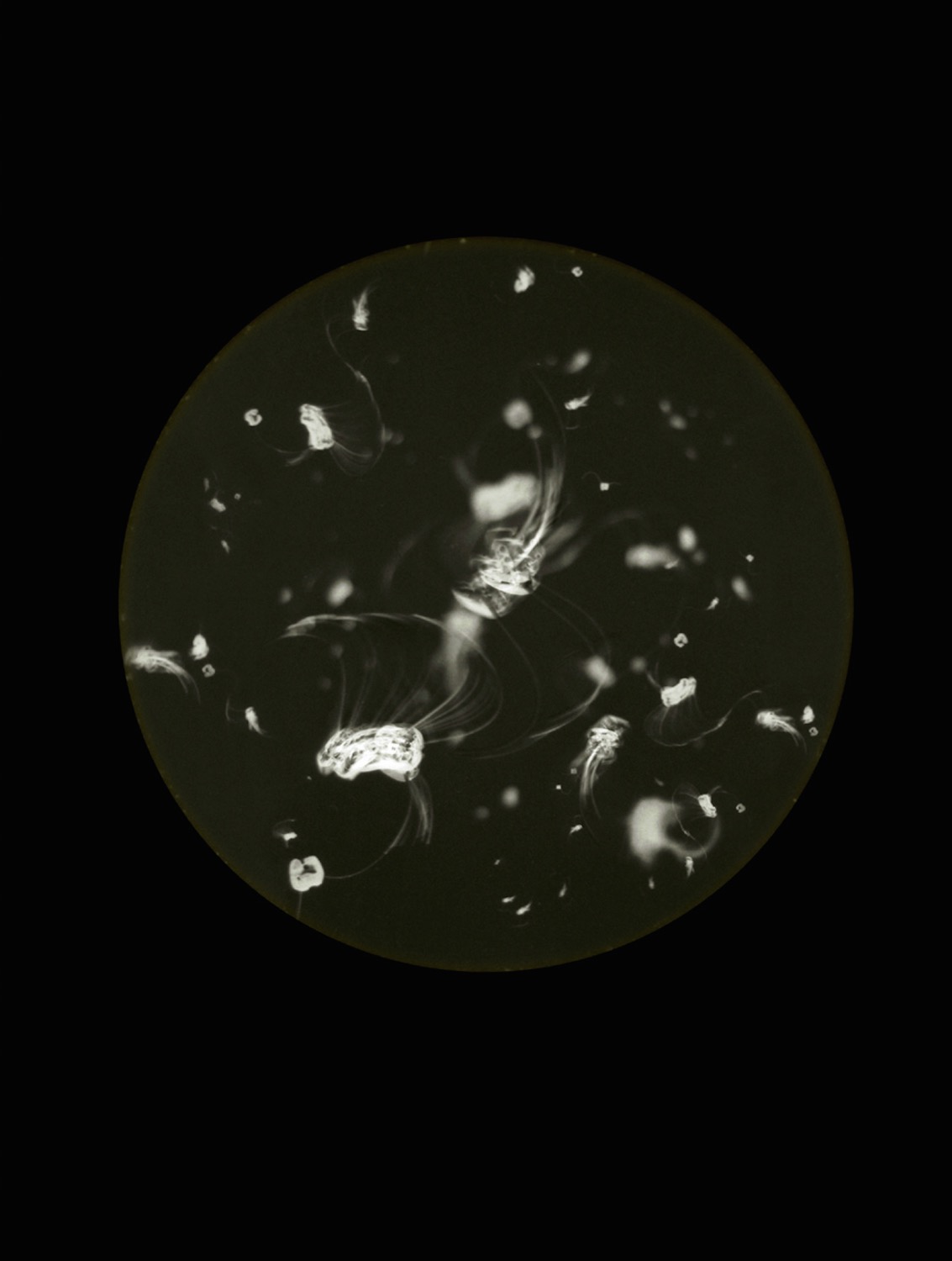

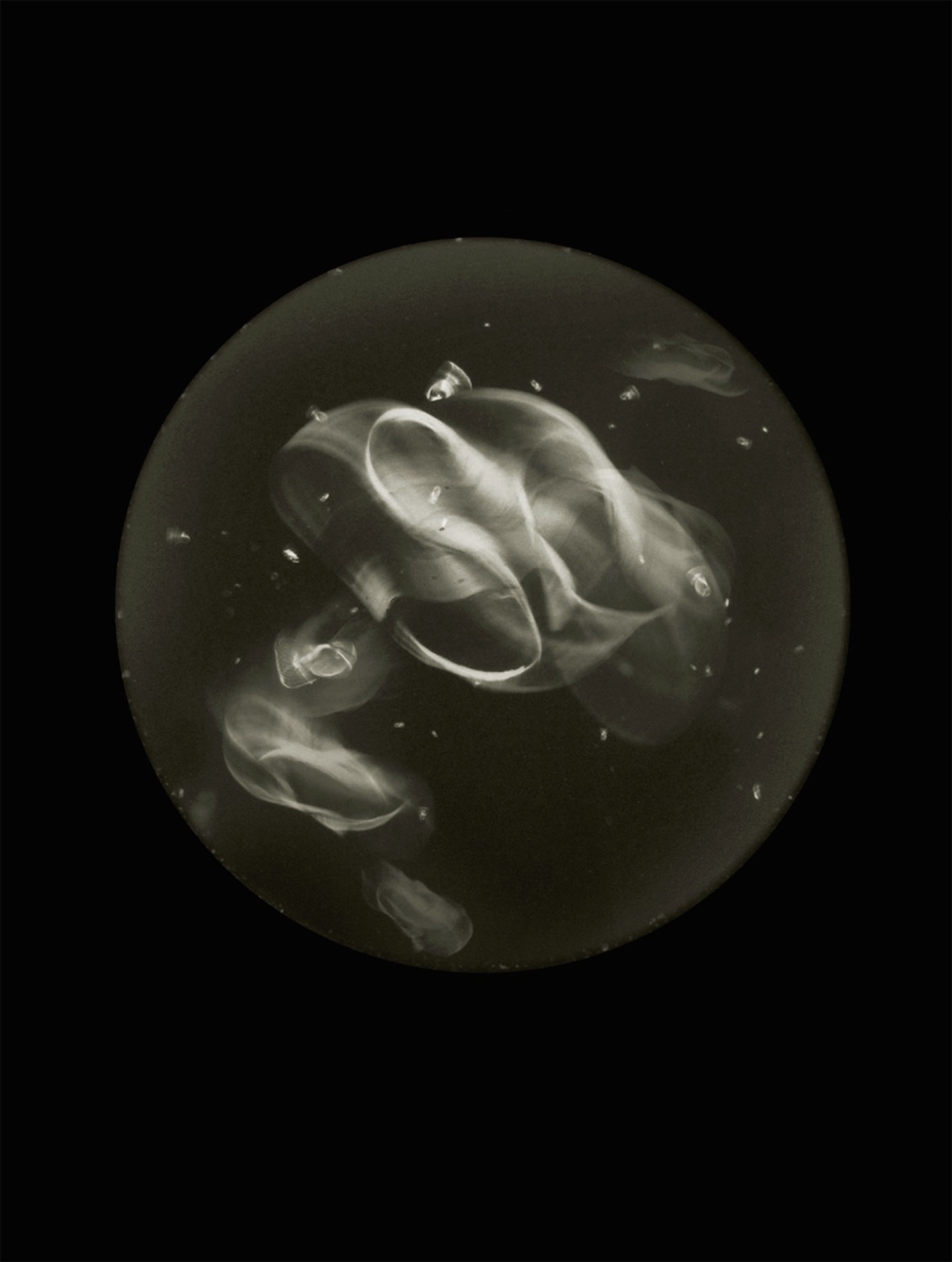

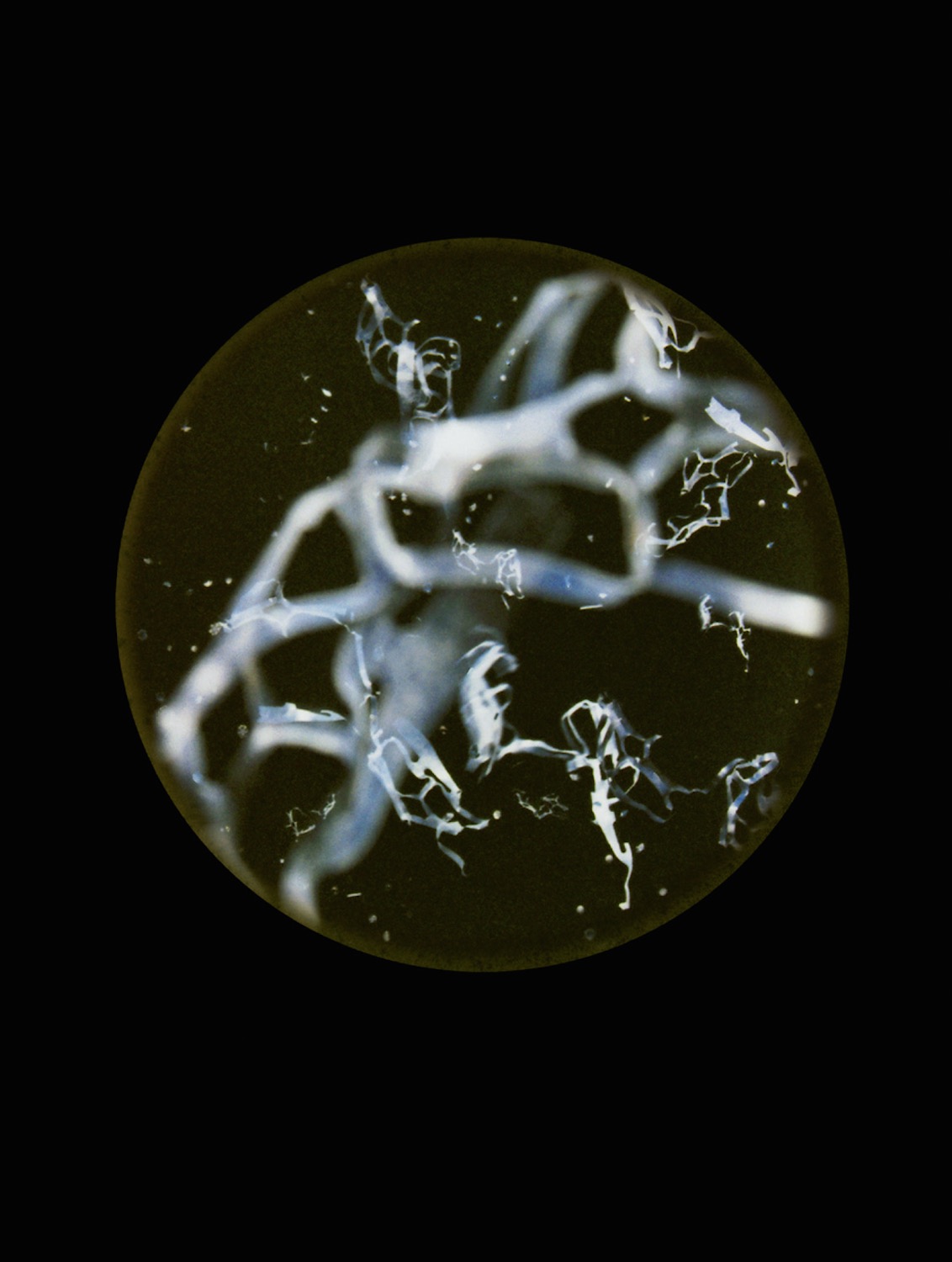

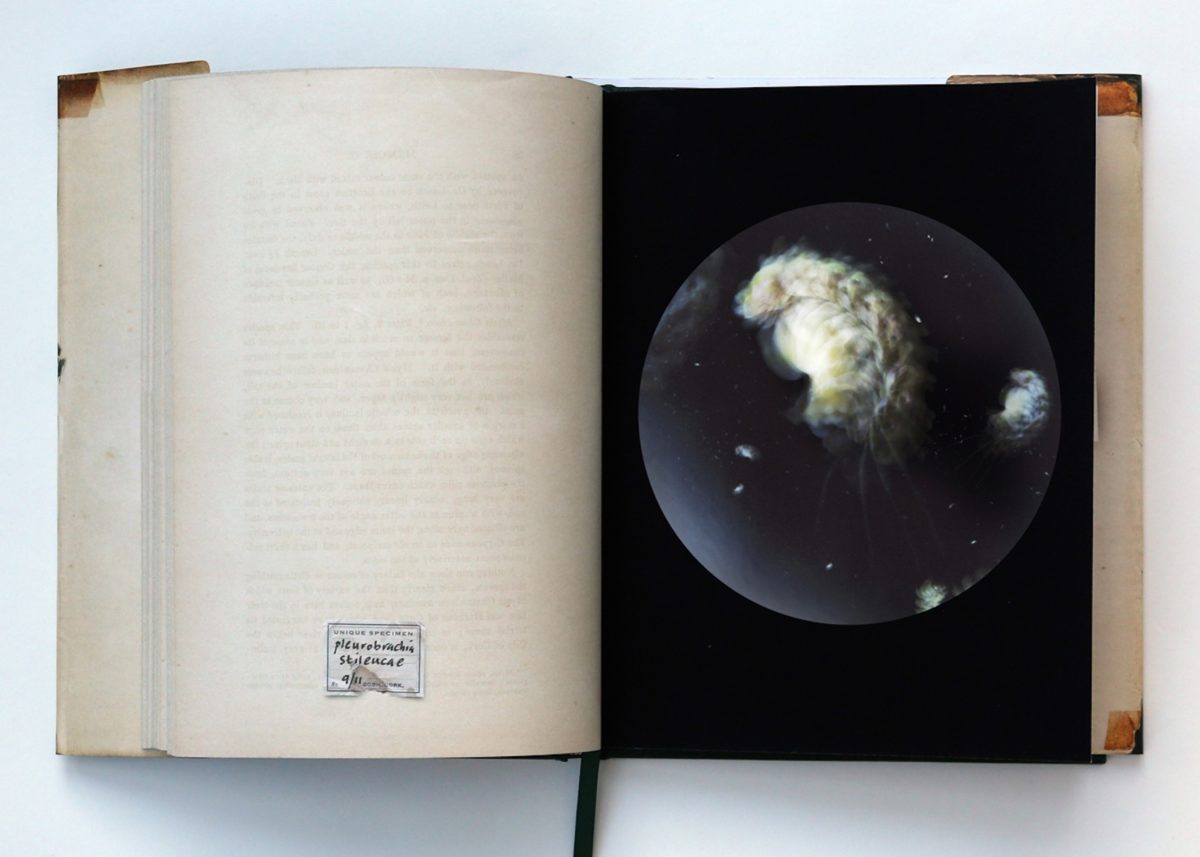

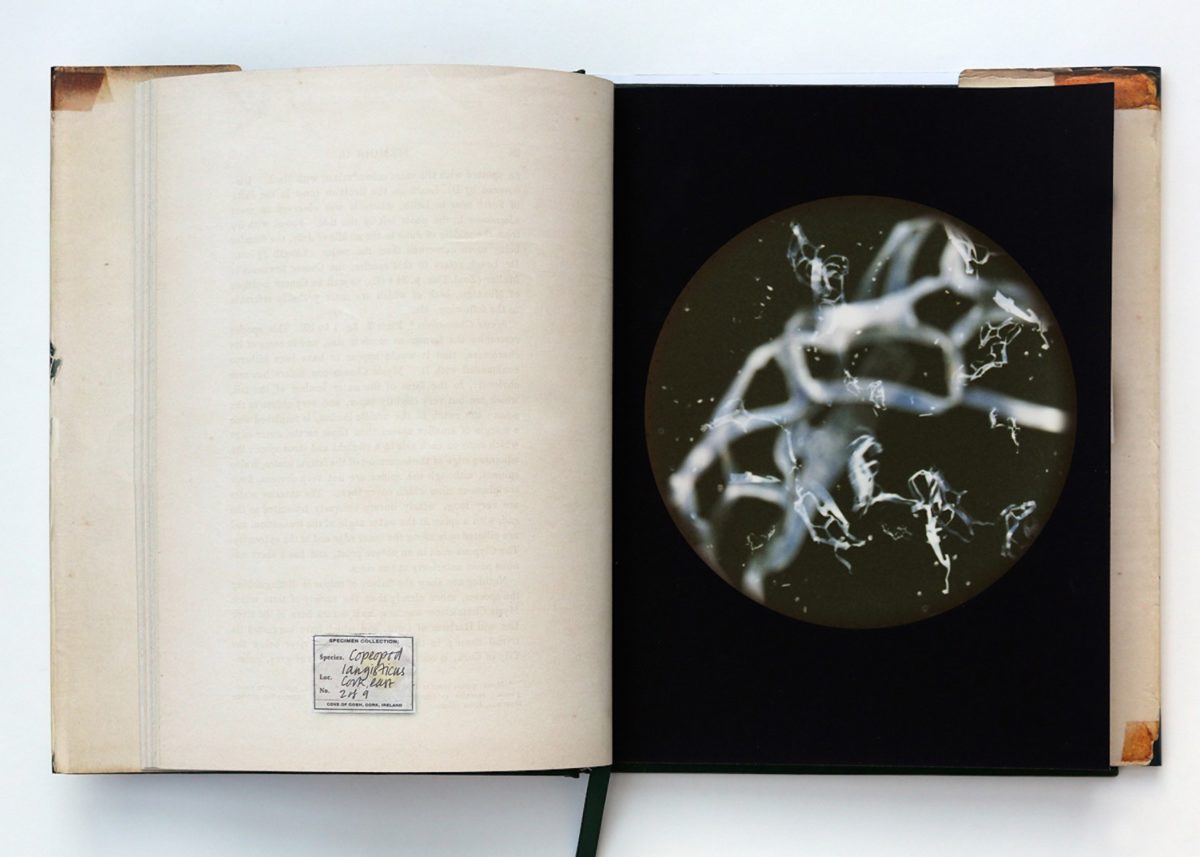

In this series unique ‘specimens’ of the animal species of plankton relate to the pioneering discoveries made by the marine biologist John Vaughn Thompson in Cobh, Cork Harbour in the 1800s.

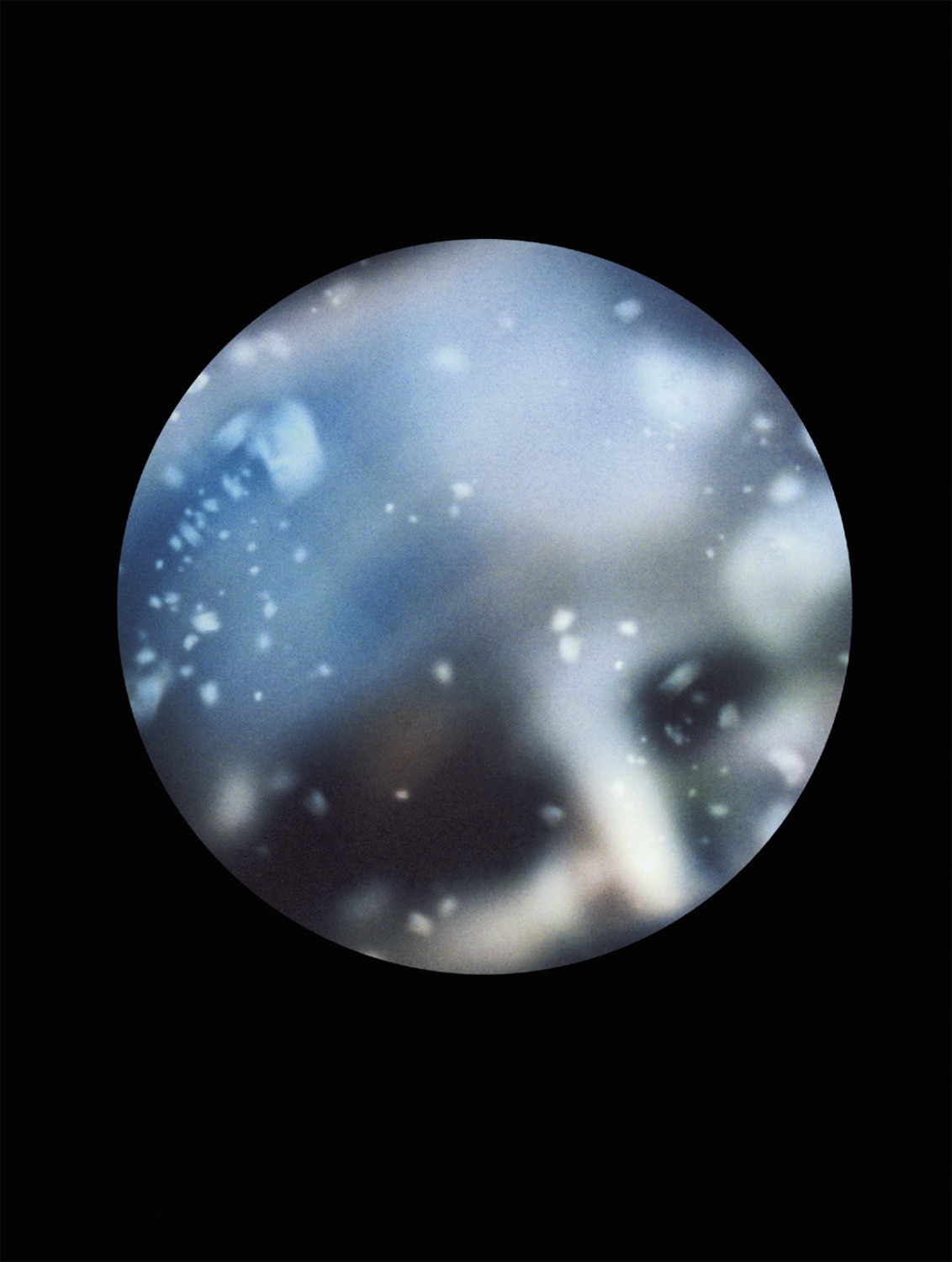

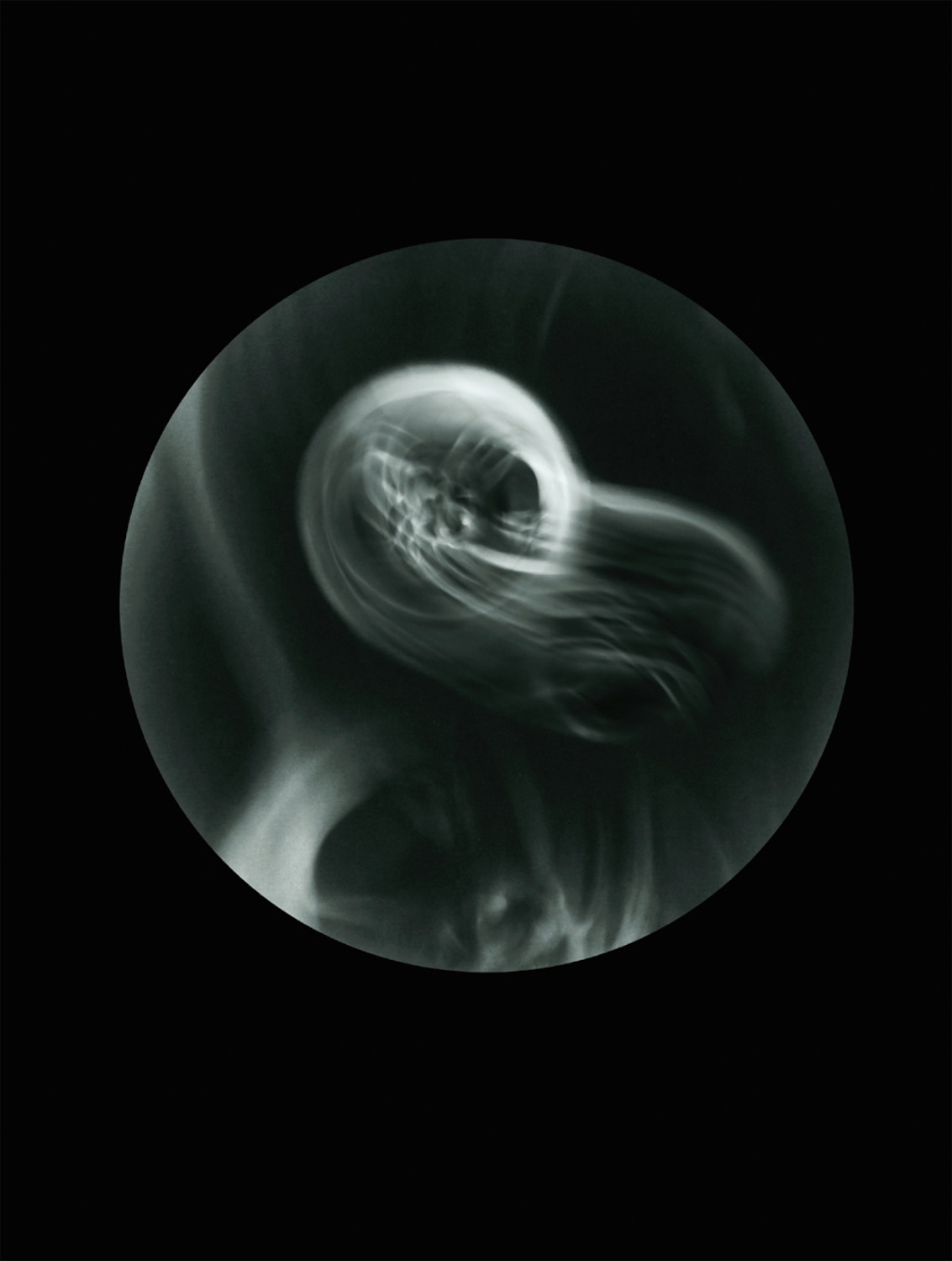

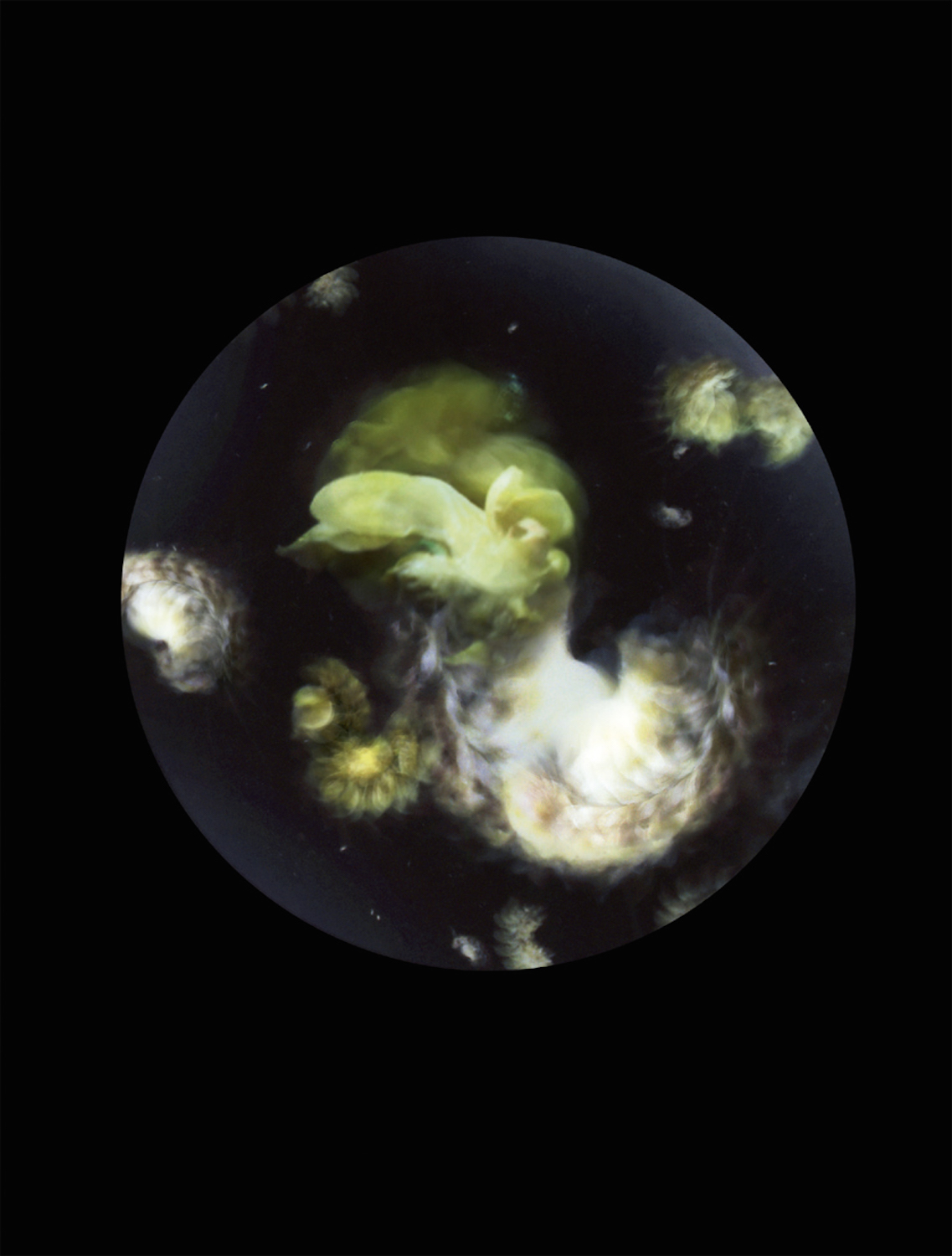

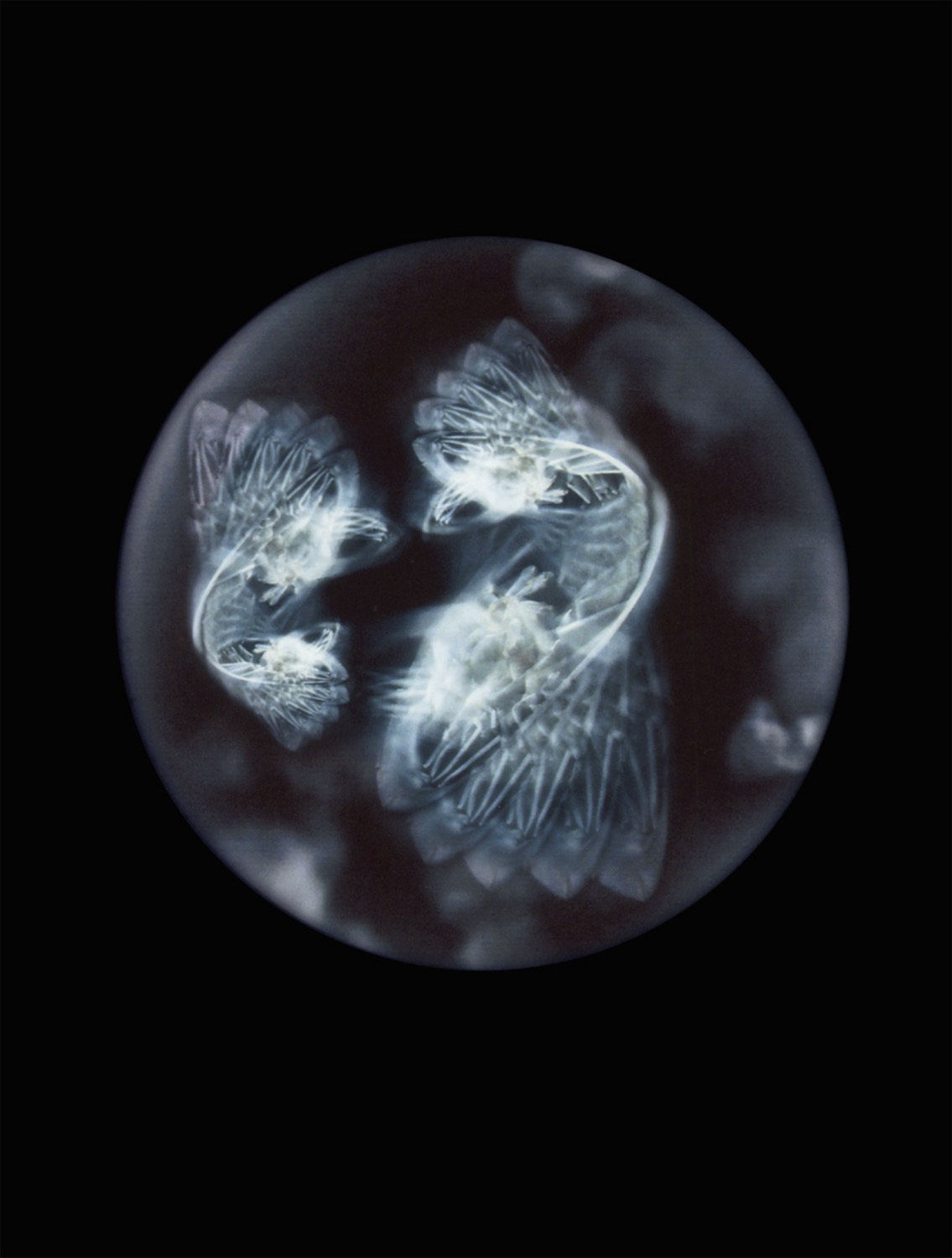

Presented as microscopic samples, objects of marine plastic debris recovered from the same location mimic Thompson’s early scientific discoveries of plankton. The work represents the degradation and contamination of plastic particles in the natural environment by creating the perception of past scientific discoveries when organisms were free from plastic. Enveloping black space evokes the deep oceans beneath. Presenting new ‘specimens’ made from recovered debris serves as a metaphor to the ubiquity of plastic as a result of man-made intervention, encapsulating in a miniature universe the much larger problem of an imperfect world.

Movements of the recovered plastic objects, recorded in camera over several seconds, represent the movement of individual plankton in the water column, which also parallels with planets that have an apparent motion of their own.

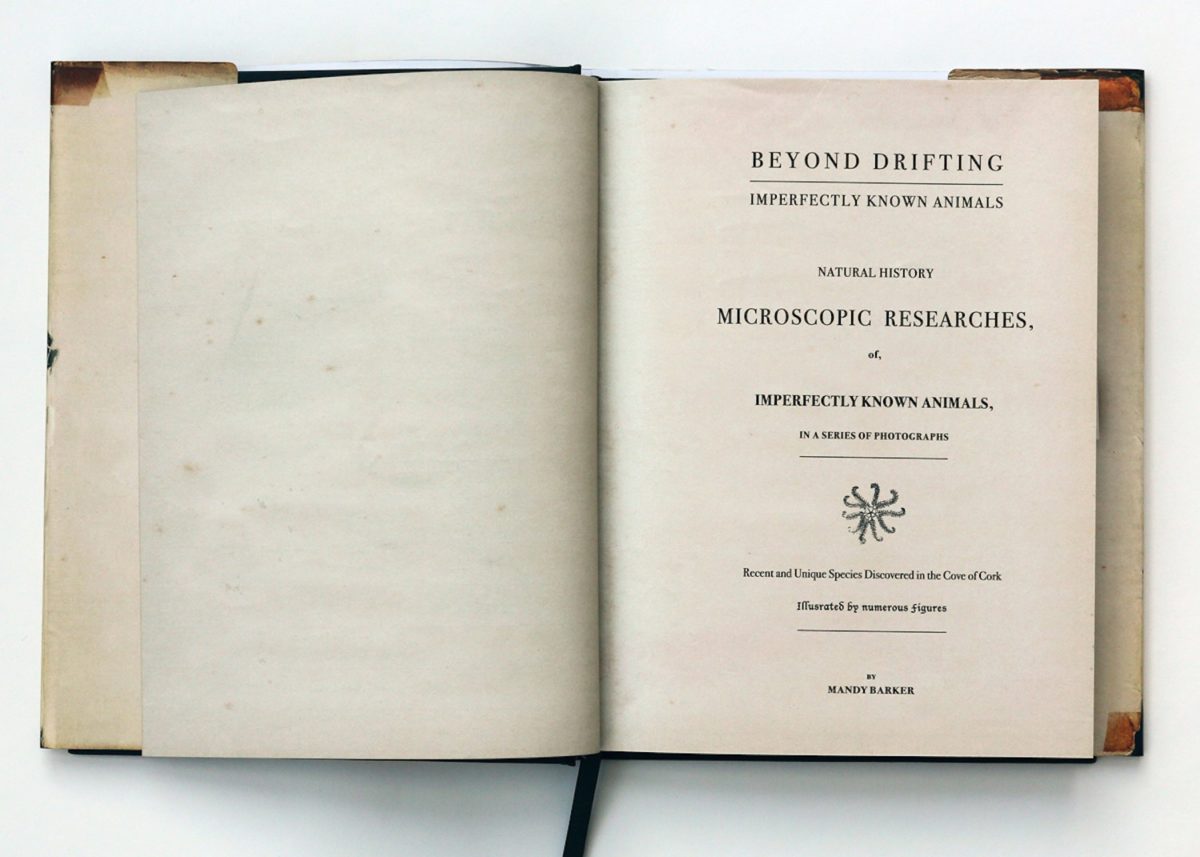

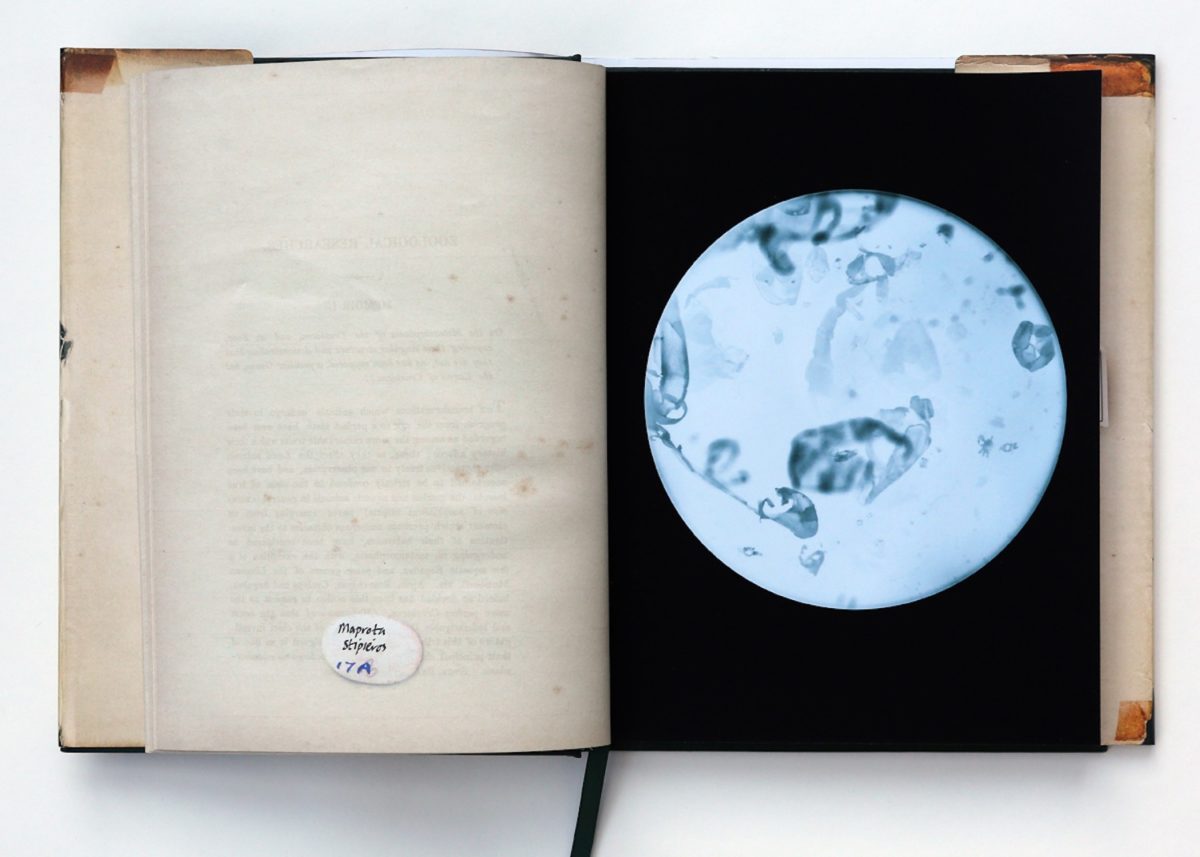

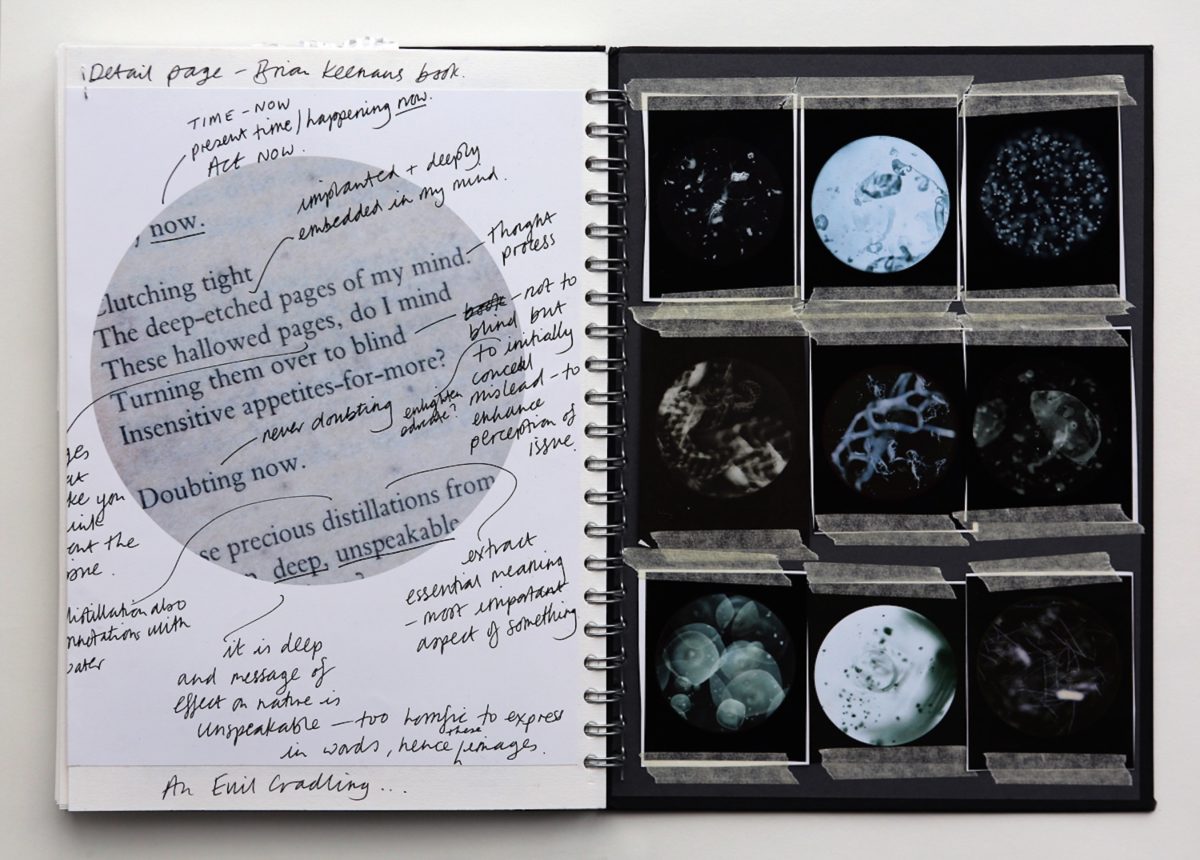

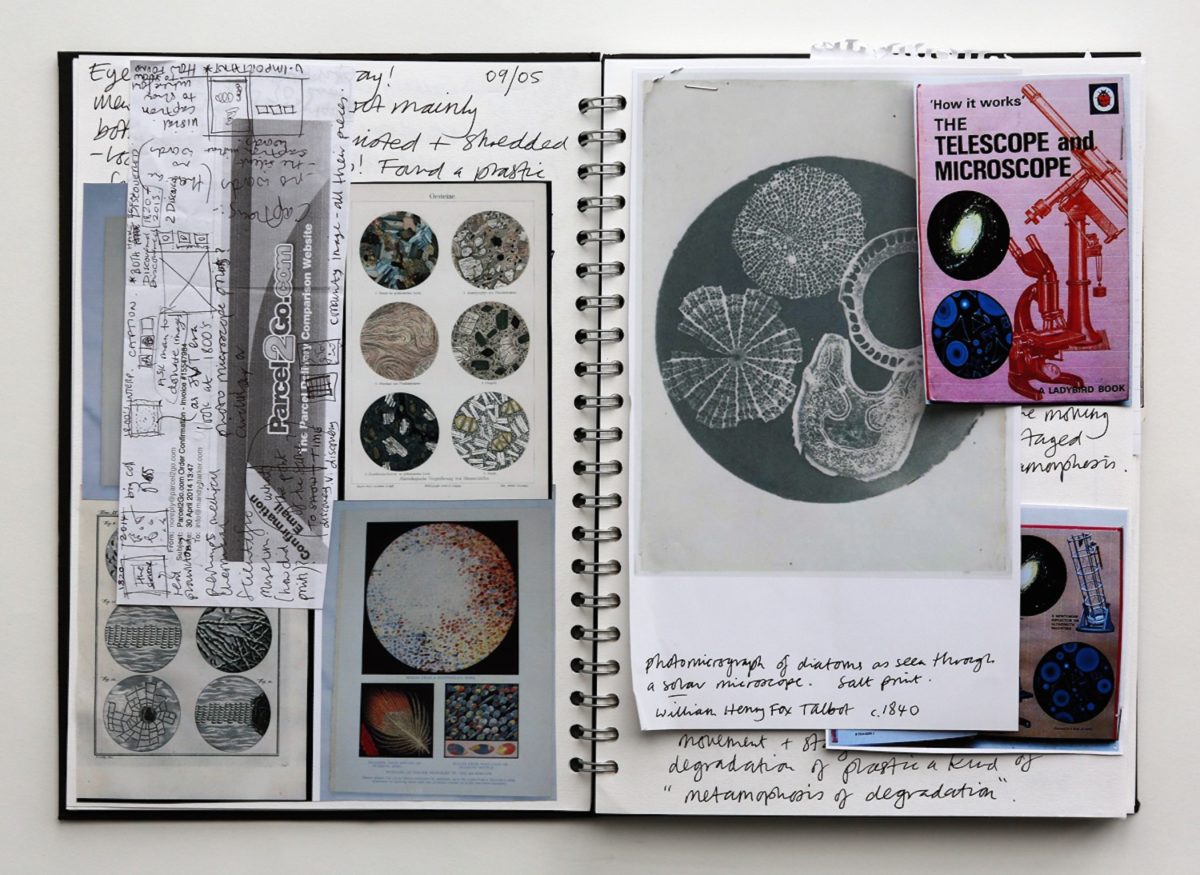

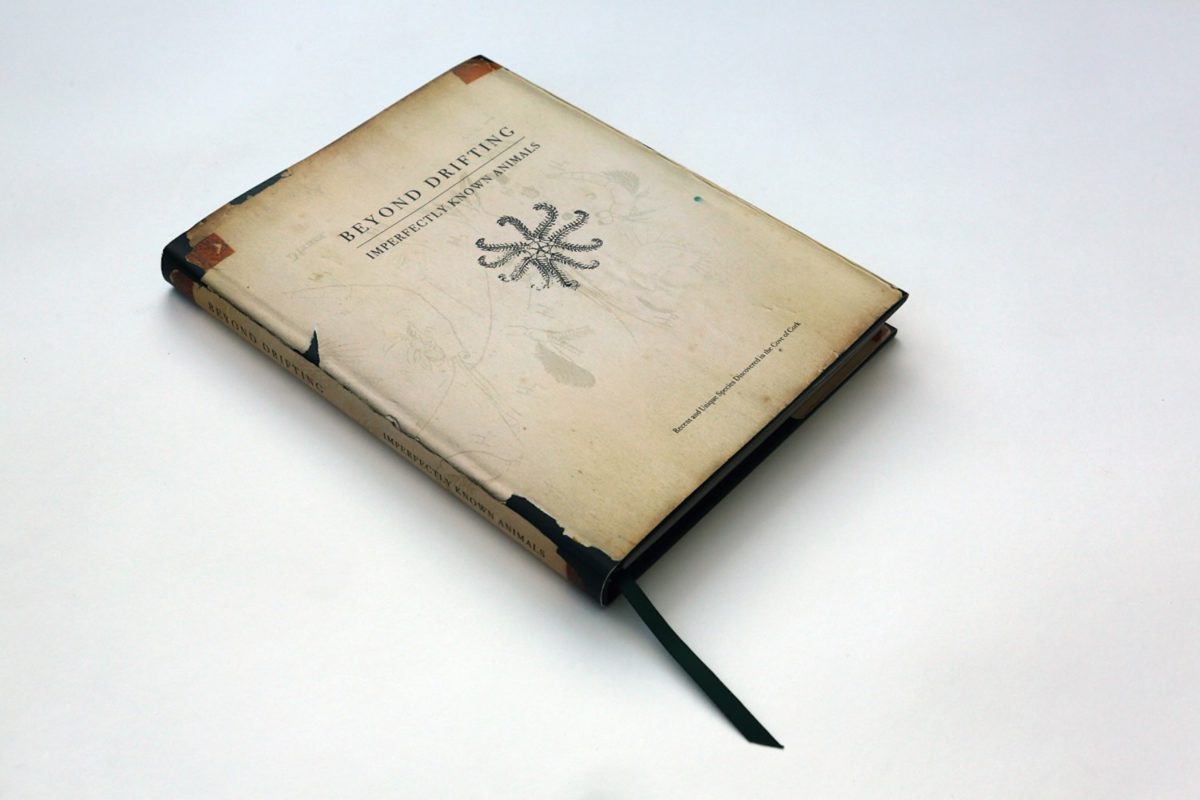

The project was conceived as a book, and all of my ideas and work start off in the form of an ideas/research notebook. I produced a book dummy to look like an antique science book from 1800s to resonate with John Vaughan Thompson’s work, his memoirs of which run in faint print on the reverse page throughout the book. The book is central to the exhibition installation alongside specimen drawers and my prints.

The book has just been published in the same manner as the dummy to reflect the age when both scientific research and plankton were free from microplastic particles.

PW: What does shooting on expired film and faulty cameras bring to the series, both to the concept and final image?

MB: The series is based on the memoirs of naturalist John Vaughan Thompson’s discoveries of plankton in Cobh, Cork Harbour in the 1800s. His memoirs are titled Zoological Researches and Illustrations, or Natural History of Nondescript or Imperfectly Known Animals. As part of title for my series, from this I used the words, ‘Imperfectly Known Animals’ which relates to the fact that plankton today are ‘imperfect’ because they contain microplastics. I realized that the theme of ‘imperfection’ was becoming apparent also in the practical process when the camera I was using – a Canon EOS 500 – failed to wind on the film, leaving a double exposure on half of the frame. This is a known fault with this camera, ‘sticky shutter syndrome’, which some say is caused by the foam light plastic seal that over time has deteriorated. The camera is between 21 and 24 years old. I liked the way the idea of imperfection spilled over into the practical image making process so I continued to use the same camera which broke three more times with the same problem. I used a total of four cameras bought from ebay. Using out-of-date-film, I felt, also reflected imperfection and combined, produced the effects I wanted to portray. In this case the work is not about producing perfect images but about the perception of an imperfect world.

Another aspect of imperfection was by way of the captions. Nomenclature is the description given to devising new scientific names, of which each specimen has been given, imitating early Latin origins each name contains the word ‘plastic’ hidden within its title. For example: OPHELIA MEDUSTICA

Specimen collected from Glounthaune shoreline, Cove of Cork, Ireland

(Pram wheel)

PW: Can you talk about the passive nature of the floating plankton and their very active impact on the food chain?

MB: Plankton are a diverse group of organisms that live in the water column, drifting, not able to swim against the current. Plant-like cells, many smaller than the diameter of a human hair, underpin the marine food chain, provide the world with oxygen and play an essential role in the global carbon cycle. Without these remarkable creatures the oceans would be a barren wilderness, there would be no fish in the sea, we would have no reserves of oil or gas and the Earth’s climate would be much different. At the very base of the food chain phytoplankton are ocean’s ‘primary producers’, they provide a crucial source of food to large aquatic organisms such as fish and whales, and indirectly to humans. Plankton play a key role in life and are perhaps the most vital organisms on Earth.

PW: How do the photographs help us to understand the relationship between plastic and the degradation of the planet, and on a larger scale, the human impact on the planet?

MB: I hope that on viewing these ‘specimens’ of an almost hidden world in a droplet of water, people will connect with current concern about the overconsumption and disposal of plastic waste around the world. The aim is to increase awareness and engage an audience with the marine debris issue and to think about what plastic they use, re-use, and refuse.

Art can be a powerful form of communication in providing a visual message when sometimes over-complicated statistics or articles are difficult to understand.

If, at best, my work can educate people to change their habits and lead them to positive action in tackling this increasing environmental problem – or at the very least cause people to think, then I will have achieved my aim.