On the eve of Mike Mandel's major exhibition at SFMOMA, we caught up to talk about his projects, approach and long term collaboration with Larry Sultan.

Photoworks: Hi Mike, thanks for taking the time to talk to us before your opening at SFMOMA. Can you tell us more about Good 70s? How did the exhibition idea come about?

Mike Mandel: Good 70s, the exhibition, is based on the boxed set of books and other printed matter that comprise Good 70s, the 2015 publication produced by D.A.P. and J & L. Books. The show is a way to take the projects out of the confines of the original container (book, poster, packs of trading cards) and enable the curator, Sandra Phillips, and I to extend the presentation of the work on the wall, in vitrines and in other new ways.

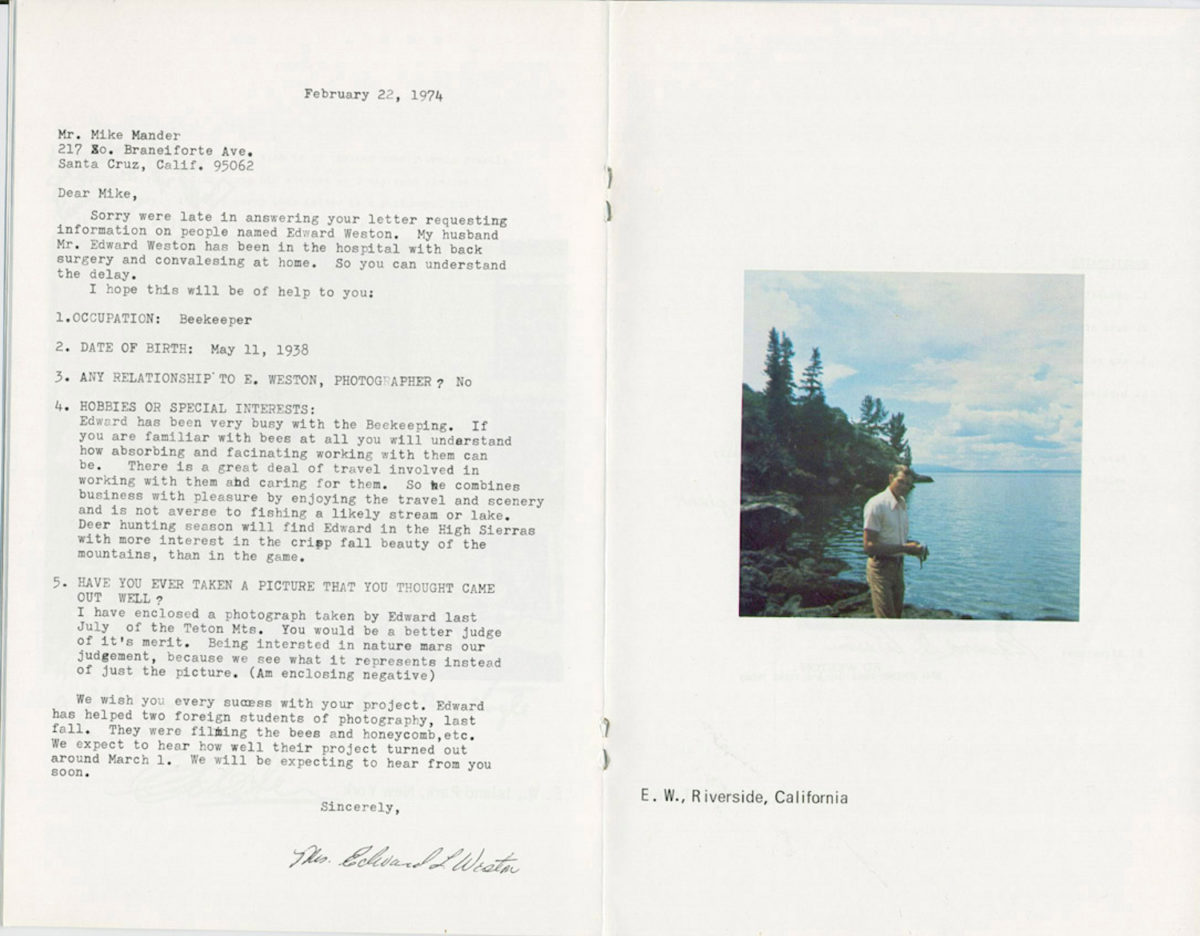

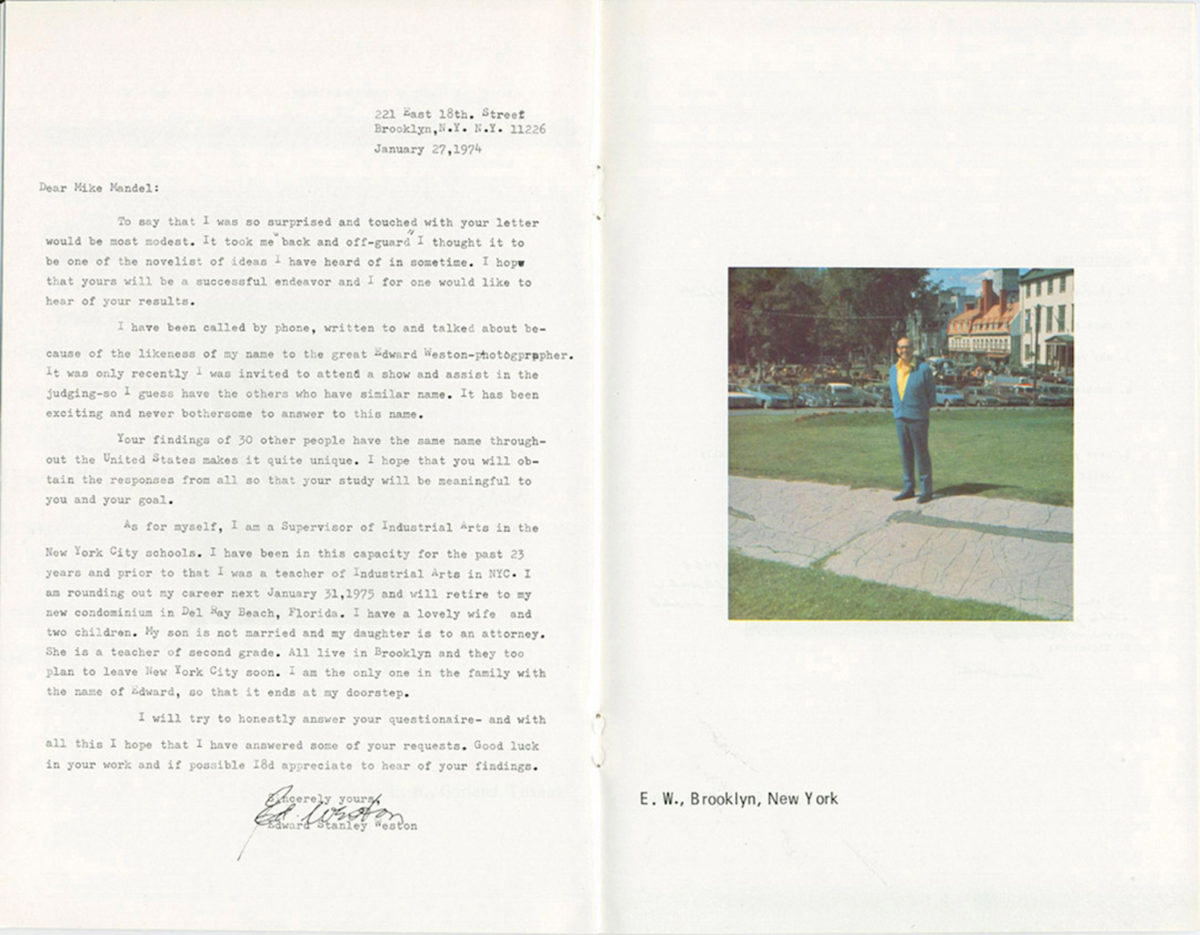

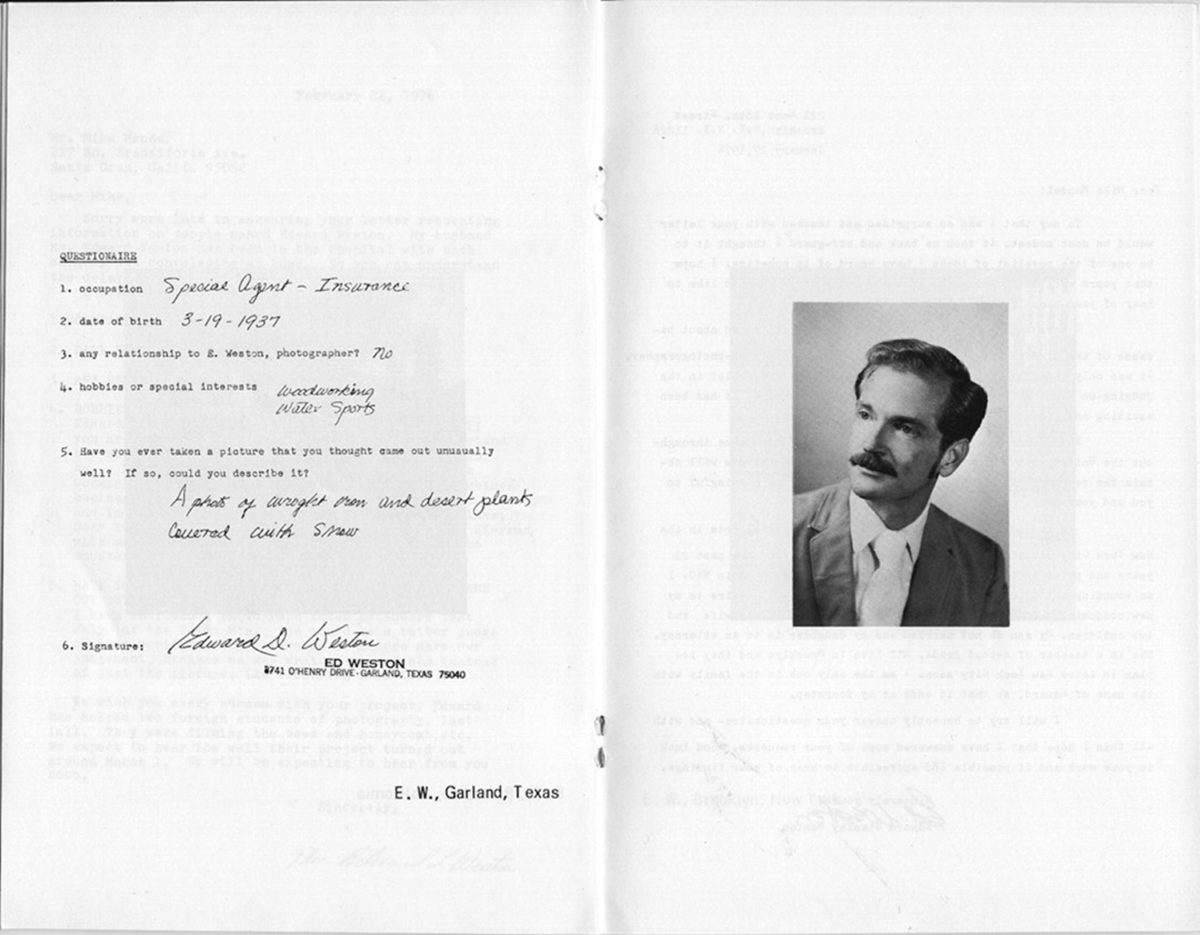

For instance, I’ve taken two full sets of the Baseball-Photographer Trading Cards and placed them on the gallery wall with recto and verso on top of each other. In addition, I’ve identified a specific Topps baseball card from the 1958 set (the first set of baseball cards that I collected as a 7 year old) and placed one of these cards that visually connects with the pose of the photographer below, or perhaps relates on other levels: similar names, gestures and expressions. In another translation to gallery, every page spread from Seven Never Before Published Portraits is laid next to each other in a vitrine, while photographs made by Edward Weston, the photographer are placed on the gallery wall opposite. The gallery served as another kind of lab to play out the work differently, which was a challenge both to the curator and myself as we had to negotiate different strategies that were comfortable (and affordable). Sometimes we agreed, sometimes not. So the exhibition is really a product of that collaboration between Phillips and myself.

The 1970s was a very productive period in my career. The projects include:

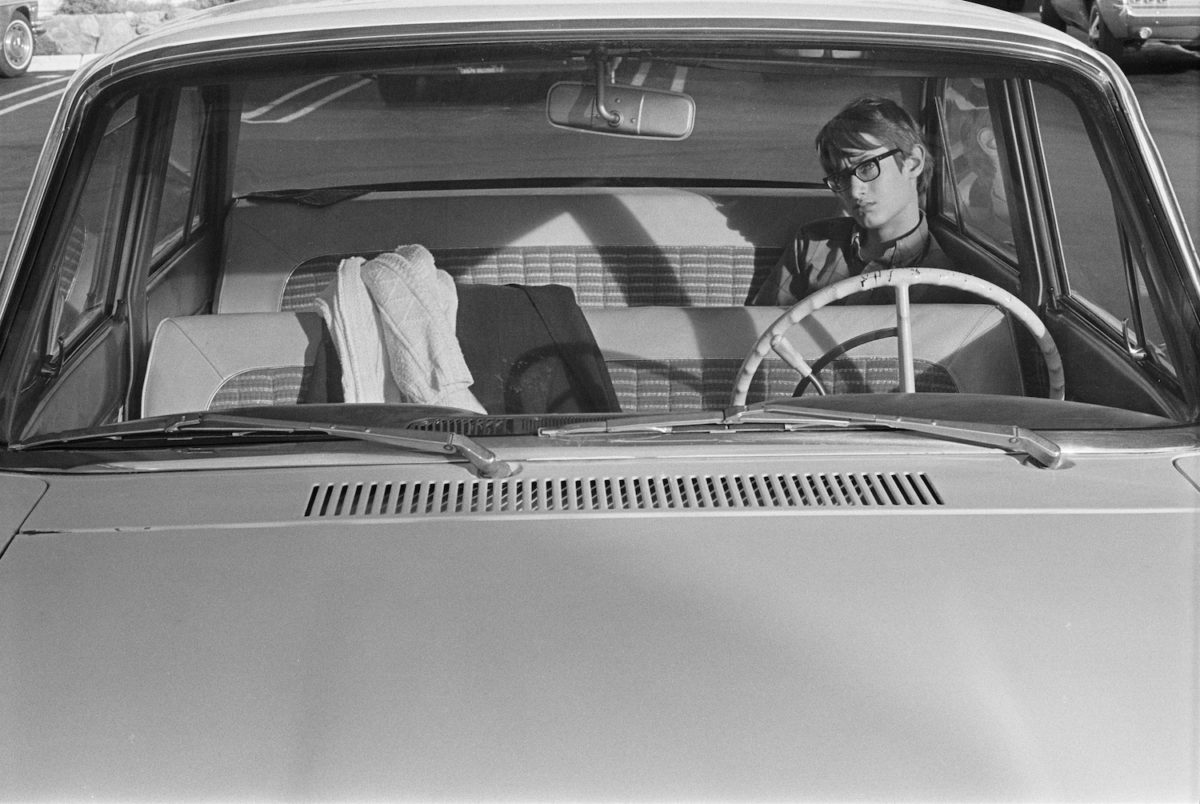

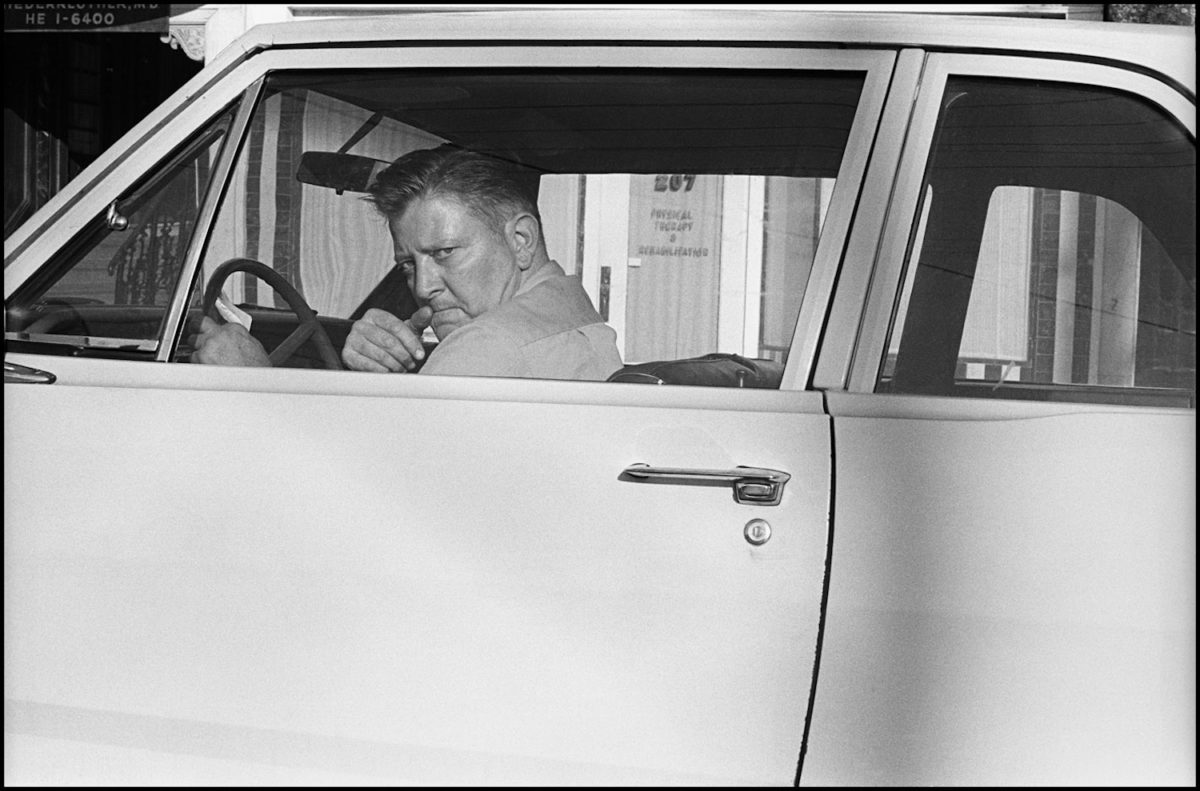

1970 People in Cars, series of images now re-published in 2017 as a book with additional images from my archive from the project.

1972 Myself Timed Exposures, book

1972 Don Drowty The Famous, film

1973 Mrs Kilpatric, book

1973 Billboards in collaboration with Larry Sultan (1973 Emeryville, 1974 Cornucopia, 1975, Oranges on Fire, 1976 Sixty Billboards, 1978 Ties)

1974 Seven Never Before Published Portraits of Edward Weston, book

1974 Boardwalk Minus Forty, series, now published as a book in 2017 as part of TBW’s subscription 5 series

1974 How To Read Music (book in collaboration with Larry Sultan)

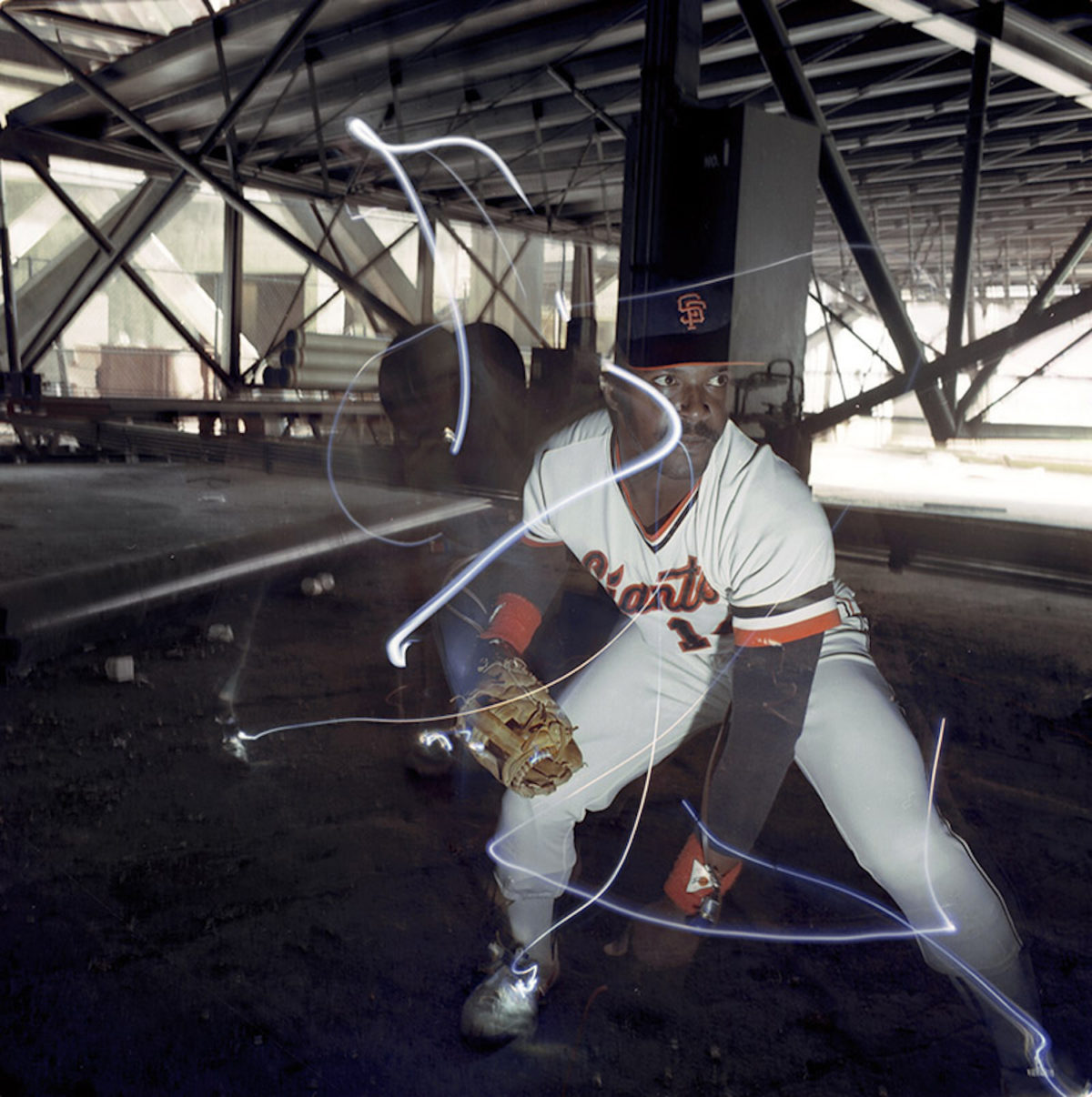

1975 The Baseball-Photographer Trading Cards

1977 Evidence, book, in collaboration with Larry Sultan

1979 SF Giants: An Oral History, book

The collaborative projects with Larry Sultan are not in the Good 70s show per se, but exist as a gallery room within Larry Sultan’s retrospective Here and Home exhibited at SFMOMA concurrently.

PW: Is there a particular feel of that period that your work captures?

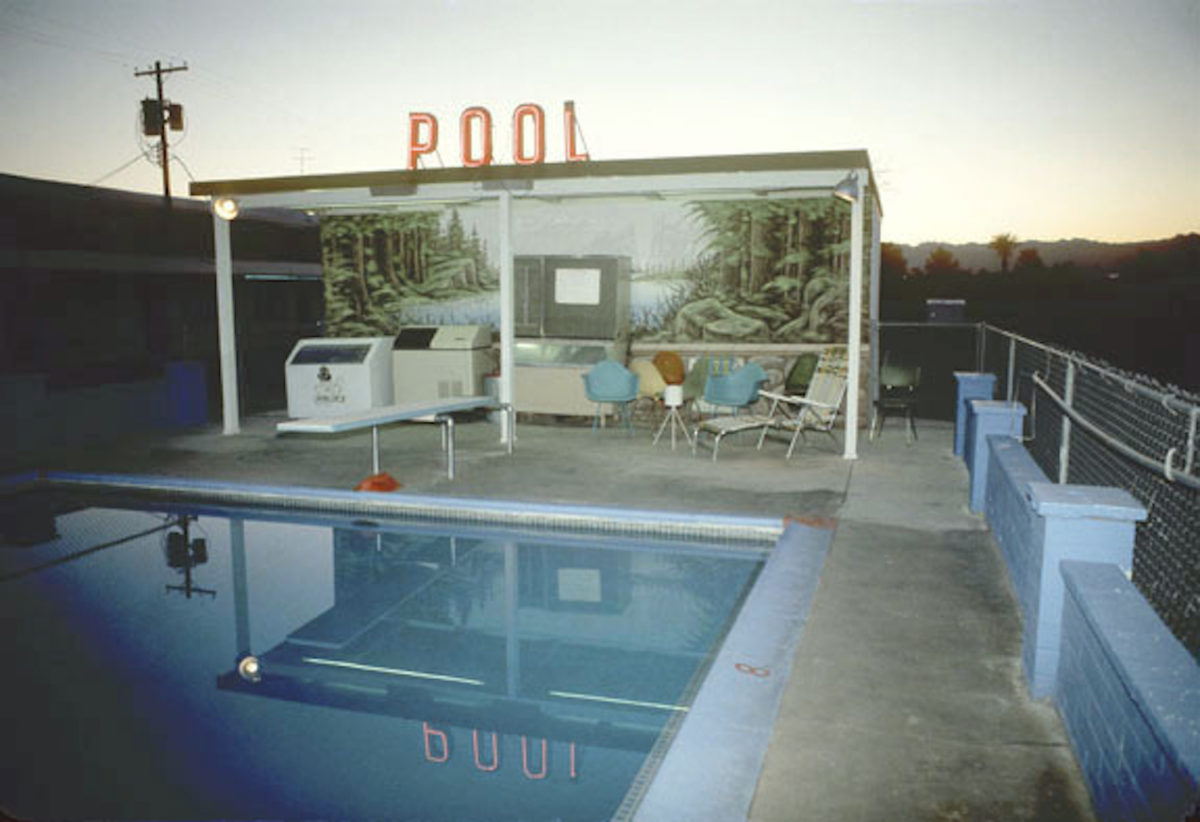

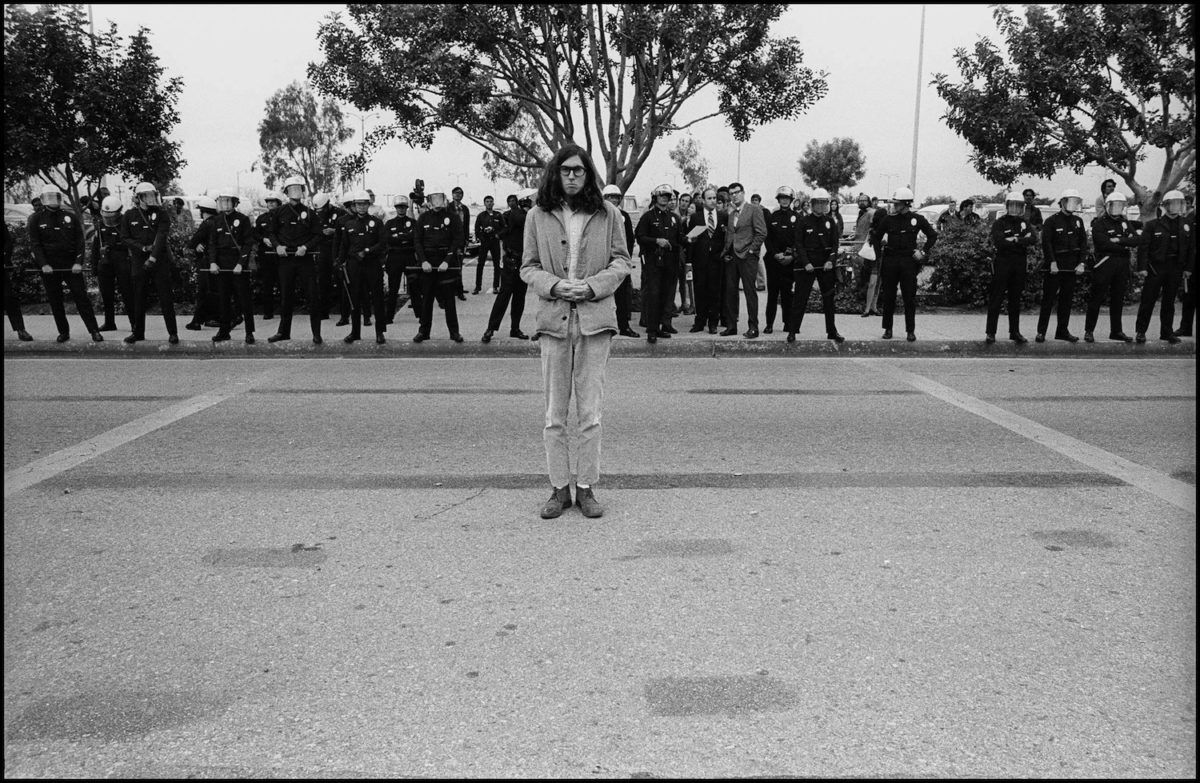

MM: I grew up in the 1950 in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles and stayed there until I moved up to San Francisco in the early 1970s.

It seemed that the place had no history. Everything was new, and there were more things coming. The Valley years of my childhood, the 50s and 60s, were a time when the farms and rural landscape before World War II were becoming, as Ed Ruscha would call it, “a real estate opportunity.” Can’t say whether this was good or bad. At the time it just seemed inevitable. But when your whole world is shopping malls and billboards and asphalt, and the Little League field a few blocks away is suddenly torn out to become a section of the Hollywood Freeway, you learn to develop a sense of humor about the unbridled commercialism that the Valley seemed to celebrate. Later in life, when I visited the east coast I thought how decrepit all these old buildings looked; like the place was just one natural disaster from falling into the sea. So the Valley seemed more like me in many ways. It was more like how I saw myself: growing up without concern for the past, but instilled with a drive for success.

But these were the times of the larger counter-culture for not just Valley kids but all American kids. The times of new culture being brewed with new fm radio stations where we were the audience and the music was for us. It was a time opening up to a new world of politics of protest against the Vietnam war, of questioning materialism, experimenting with drugs, having sex. I went to school at San Fernando Valley State College because I couldn’t afford to go elsewhere. My parents were barely getting by, and I remember my semester tuition was $47, so that was my only choice. But it turned out just fine. I started out as a political science major but ended up with a philosophy degree. And it was here that I discovered myself as a student of photography with Ed Sievers as my teacher. As far as my art education at Valley State, I took no other classes other than photography. Sievers was my guide, my mentor. He was accessible, down to earth and a free spirit, almost ascetic. He lived in a studio apartment near Venice Beach, no furniture other than a bed. He had an enlarger in his kitchen where he never cooked (at least at that time). It was a complete alternate lifestyle compared to my staid conservative childhood living with my parents and sister in a two bedroom apartment in Van Nuys. Sievers taught me how important it was to learn to see. He was a student of Harry Callahan at RISD. And like Callahan, he had trouble with verbal communication, although with Sievers it was because of a stutter rather than a philosophical aversion to talking about art.

The photo community was connected in LA via Robert Heinecken. He held the position at UCLA and he brought people from all over LA together. He supported an experimental attitude toward photography. I never took a class from him, but the community was so tight, we’d all get together at photo openings and connect. He would invite photographers from outside the area to speak, and we were all invited in. Sievers may have been one of the great photographic seers of the time, but Heinecken was the consummate conceptualist. Heinecken pushed the limits not only of the form of photography, but his transgressive approach to subject provoked and inspired. Along the way he became a friend and mentor as well. When I initiated the Baseball-Photographer Trading Card project, we met at a coffee shop in Santa Monica and he gave me suggestions as to who to photograph on my trip around the country. And he gave me a check for $100, for, as he said at the time “a few more days on the road.”

PW: You were a long time collaborator with Larry Sultan. Can you talk about your approach to making work together and what that can bring to a practice?

MM: I’m going to quote from a letter that Larry wrote to Mark Johnstone in 1984:

“Like all relationships, the motivations for getting together and staying together are very complex and somewhat inscrutable. It still amazes me that two people with such different personalities and artistic sensibilities have been able to work together over the years. …When I first met Mike I was ambivalent about his work – it was very different than mine, more cynical and stylized. Yet I was very impressed that he had the guts to publish his own book and that his work was using humor as a device for social criticism. Mike had entered the (SF Art) Institute a year after me and by the time he arrived my disappointment with the place and the “teaching” had me in a state of withdrawal and bitterness. Because I had no previous exposure to art talk, the seminars were confusing ordeals and in general, the environment unsupportive and competitive. I had always found it difficult to keep my self-doubts from occasionally flooding me and spreading havoc and mud throughout the house – at the Institute it proved impossible. And here was Mike, confident to the point of cockiness – and his work dealing with social realities that I had disinfected from my work, but not from my consciousness. True the idea of a billboard was the foil for our collaboration, but for me, working with Mike was a means of recovering the alienated parts of myself. It also helped to have someone telling me that we could do what seemed impossible and we were important – and let those bohemian snobs choke on the capuchins and Surrealist drivel. It was just what I need – but it also presented its own problems.

I agree with Mike that our process is a dialectical one, that our differences serve as strengths and that we act as safety valves for each other’s excesses. The problem for me was that my excesses had yet to take on a definite shape as artwork, and thus the need to bring my own work to some kind of resolution began to be a priority. My work has usually been more introspective than Mike’s, my intention a bit murkier and my process circuitous. I mucked around in the water for years before I had a sense of was I was doing and how best to do it. Of course, the other side of it is that during the mid 70s it was a bit painful when people would ask if I was the guy who helps Mike Mandel with his projects.

Obviously Mike and I bring things out of each other, trigger things that would have stayed inert in our individual work. On the other had, my own work allows me to go deeper into myself – to make work that is more experiential and personal. It is difficult to imagine not having both opportunities – especially since I seem to long for one way of working when I’m involved in the other. Right now I miss the fire that gets fanned when Mike and I work together – and then there are the dreams: the feeling that things are possible and the adventure is shared, that failures aren’t that serious and pushing each other to the edge is where the action is. Now, if only Mike would obey me and move down the street…”

(Larry and I always lived about 100 miles from each other and we each would travel and stay at each other’s house and spend two or three days at a time doing nothing but working together – no time out for socializing, just work! Then back to our own lives and plan the next move that would bring us together.)

PW: There is a strong sense of humor in your approach. Does that help when it comes to using improvisation or the unexpected?

MM: I’ve always embraced humor as a strategy of embracing the conflict of the overlapping, sometimes incompatible layered structures that comprise our lived experience, personal, political, familial, social, what-have-you.

I’m going to describe below Arthur Koestler’s ideas in his book The Act of Creation which had a deep impact on my thoughts about how humor, art and scientific discovery all function with similar “bisociations” intersections of ideas that lead to new discoveries.

Koestler’s fundamental idea is that any creative act is a bisociation (not mere association) of two (or more) apparently incompatible frames of thought. He argues that the diverse forms of human creativity all correspond to variations of his model of bisociation. In jokes and humor, the audience is led to expect a certain outcome compatible with a particular matrix (such as the narrative storyline); but the punch line replaces the original matrix with an alternative to comic effect. The structure of a joke then, is essentially that of bait-and-switch. In scientific inquiry, the two matrices are fused into a new larger synthesis. The recognition that two previously disconnected matrices are compatible generates the experience of eureka. Finally, in the arts and in ritual, the two matrices are held in juxtaposition to one another. Observing art is a process of experiencing this juxtaposition, with both matrices sustained.

PW: Would you say that social, political and cultural realities influence your creative vision?

MM: Yes.