Carol Jacobi, curator of Tate Britain's Painting with Light shares her thoughts on the relationship between photography and painting.

Photoworks: In its early form, photography was described as being a tool, in contrast to painting, which was recognised as a fine artform. What impact did this have on the development of photography?

Carol Jacobi: In the beginning photographs were naturally discussed in a language adapted from other pictorial arts (painting, drawing and print-making). Not all accounts of the medium were technical and the artistry of photographic methods was appreciated, as well as the science. In the 1840s, the first salted paper prints by painter David Octavius Hill and photographer Robert Adamson were exhibited at the Scottish Academy and likened to Rembrandt. In 1860s critics compared Henry Peach Robinson’s Lady of Shallot to Walter Crane’s contemporary oil of the same subject. By the 1880s photogravure vied with fine prints and photographers of the Salons of The Linked Ring group displayed their work as autonomous pictures.

PW: What lessons do you think were translated from painting to photography in terms of achieving true representation?

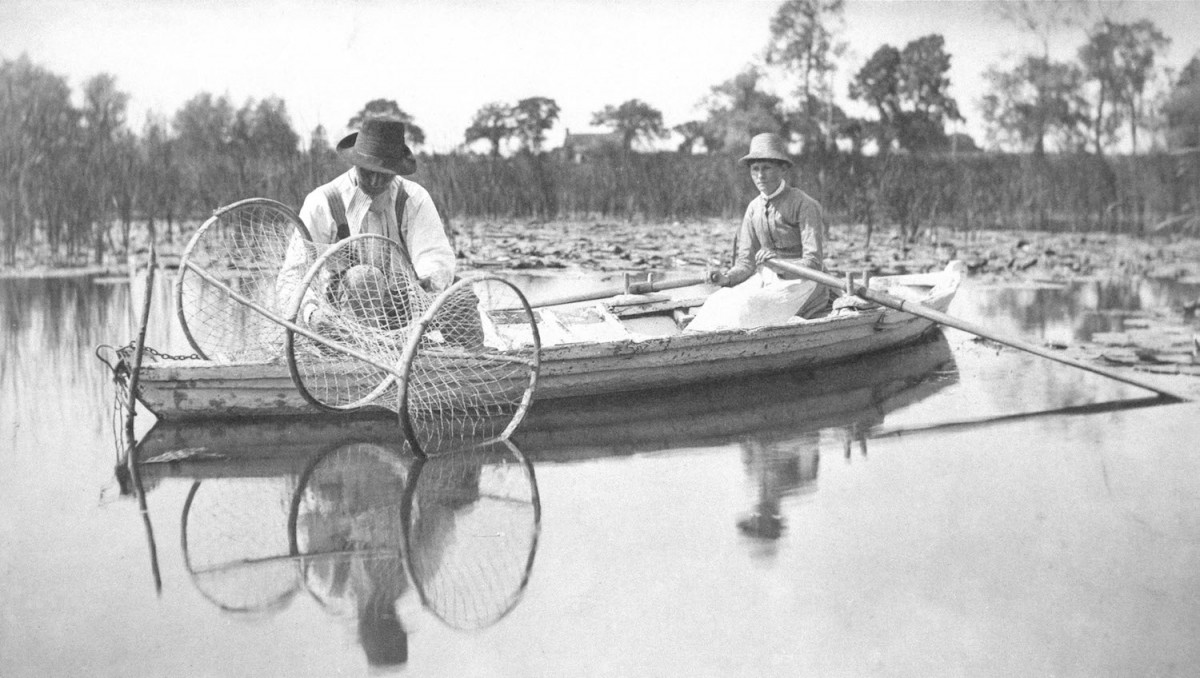

CJ: Photography emerged into an age when the desire to be ‘true’, to authentically reflect the modern world and experience, was revolutionising literature and art, most notably in the case of the Pre-Raphaelites. Photographer James Graham worked alongside painter William Holman Hunt in the Middle East with the same practical and spiritual aim of documenting the scene of Christ’s childhood. However, in the 1860s, painters and photographers of the Aesthetic movement turned away from objective detail and explored indistinctness, mystery and subjective effects; Whistler’s Nocturne’s, for example, influenced the soft, smoky Thames views of PH Emerson and Alvin Langdon Coburn.

PW: What contribution has photography made to the field of painting?

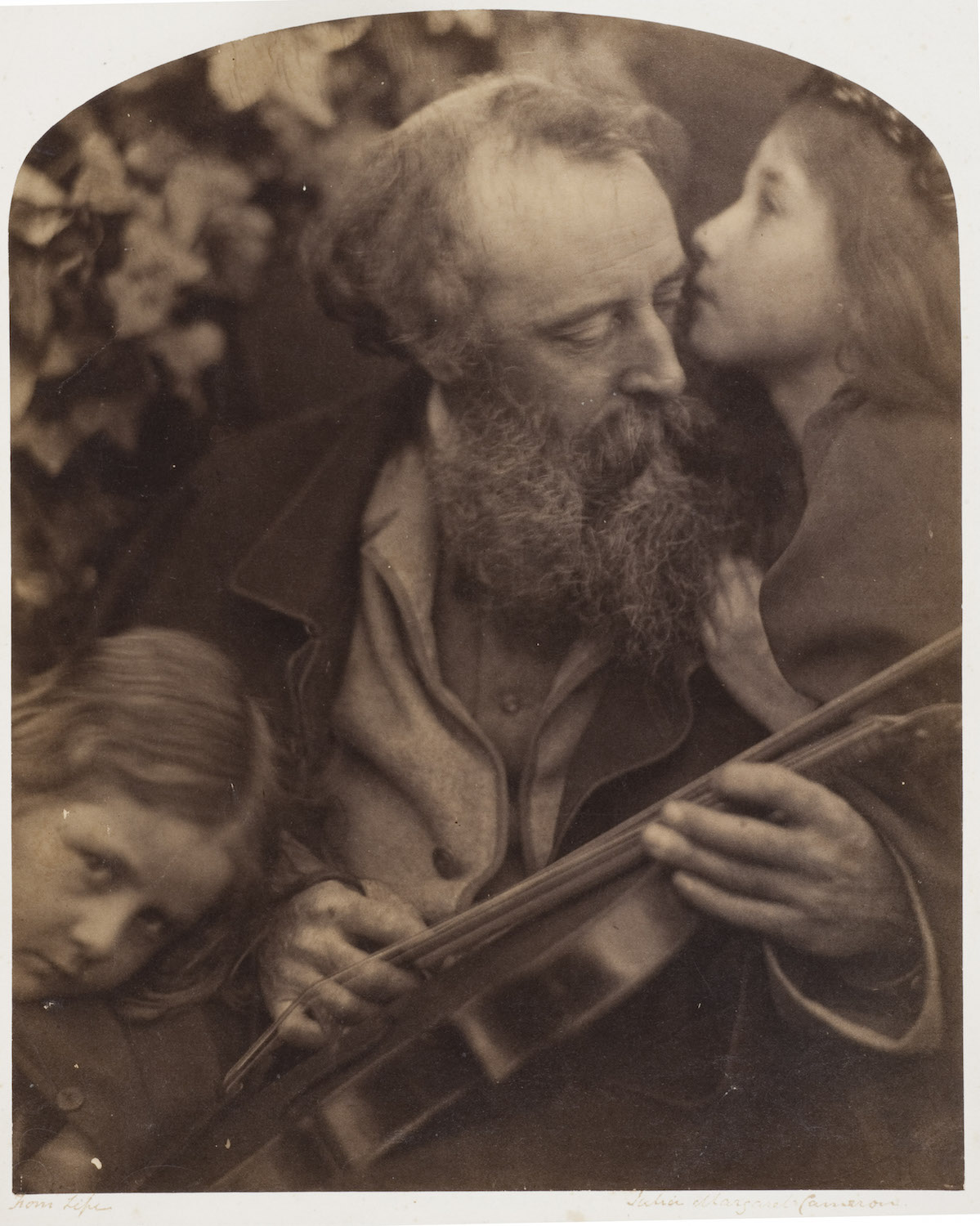

CJ: Within five years of the invention of photography, painters had incorporated them into their range of source material, using them as studies and even underdrawings. David Octavius Hill collaborated with Robert Adamson to create one of the first crowd portraits, The Disruption Picture (1843-66) an ambitious array of 457 faces, while William Etty adapted a photograph of himself with downcast eyes into an inscrutable self-portrait. Photographers and painters shared a tendency to dispense with the professional model and represent friends, family and lovers. The Aesthetic Circle, for example, which included Julia Margaret Cameron and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, explored more individualised beauty and psychological intimacy.

PW: Who do you think is currently working between photography and painting in ways that make the most of the qualities of both art forms?

CJ: We have come full circle in that photography is again generally appreciated as a medium of artifice and artistry. Henry Wallis’ famous painted tableau of The Death of Chatterton inspired provocative variations by James Robinson, in three-dimensions in the 1860s, Sam Taylor Wood’s Soliloquy II in the 1990s and Yinka Shonibare Fake Death Picture (The Death of Chatterton – Henry Wallis), 2011. Painting with Light at Tate Britain charts the early intersection of art, photography and theatre which is currently being celebrated in Tate Modern’s Performing for the Camera.