Editor Luke Dodd explains the unique position Jane Bown created for herself throughout her career.

Photographers should neither be seen nor heard

Jane’s reputation as one of the United Kingdom’s pre-eminent portrait photographers is not in doubt but it has tended to eclipse the vast diversity of her work. Over the course of more than six decades taking photographs for the Observer, Jane worked in all areas of photojournalism – everything from fashion shows to strikes to demonstrations to dog-shows to archaeological digs to beauty pageants to celebrity trials to sex-workers.

The artistic sensibility that infuses Jane’s best images makes it difficult to define her legacy. Commentators often list the things she didn’t do in an attempt to explain what is so distinctive about her work – the supreme lack of interest in equipment; the pared-back, rapid working method; the use of available light; no more than a roll and a half of film exposed on a shoot, ideally; the resistance to colour; gauging the camera settings by studying how light fell on the back of her hand rather than using a light meter; complete lack of interest in or research about a subject prior to the shoot. Most famously of all, Jane was extremely reluctant to speak about how she worked – her often quoted mantra was, photographers should neither be seen nor heard. She was the absolute antithesis of the macho Fleet St stereotype.

This pared-back aesthetic was carefully calibrated by Jane to neuter the worst aspects of ego and narcissism to which so many photographers succumb. There was nothing affected about this reserve, rather, it reflected her deeply intuitive method of working and was designed to make each new encounter as fresh and spontaneous as possible. She was profoundly democratic in the way she worked – it mattered little to her whether she was photographing the Prime Minister or sex-workers. She had an innate understanding of the predatory nature of photography and consciously resisted it by working quickly, simply and unobtrusively, whatever the assignment. What was important for her was the taking of the photograph, not hanging out with celebrities, or endless exhibitions and publications.

Jane claimed that her gender never hindered her in any way but I think this had a lot to do with her lack of competitiveness. It never occurred to her to work anywhere other than at the Observer – she talked of it as her ‘home’ – and she quite literally accepted any assignment without question. It might also have had something to do with the clear class division that existed in newsrooms of the period: the editorial staff were, by and large, Oxbridge types whereas photographers and darkroom technicians tended to come from more middle and working class backgrounds. Jane, I’m fairly sure, was given a degree of license because she spoke with a very clipped, posh accent, and was deliberately obscure about her background. She was able to straddle both worlds easily. She was also a favourite of the legendary editor (and proprietor) David Astor – he would often seek her out after a shoot to see what her impression of the subject had been. And in the very male-dominated Fleet Street world, her gender may have worked to her advantage in awkward situations – Jane’s generation were adept at using courteous behaviour towards women, often little more than thinly disguised misogyny, to their advantage.

While Jane’s work is instantly recognisable, it is curiously devoid of her own personality or political prejudice. She was an admirer of Margaret Thatcher and photographed her in Downing Street in 1983. She recalled the shoot with amusement – the Prime Minister banished the reporter to give Jane her complete attention. In frame after frame, Thatcher meets Jane’s lens head on, her clothes and hair like battle armour. But, patient as a cat, Jane bided her time and then three frames in quick succession, each one increasingly close-up, as the Prime Minister reaches her hand up to replace a stray strand of hair, the mask slipping almost imperceptibly, the merest flicker of doubt around the eyes. I once asked Jane if she thought she had ever compromised somebody by taking an unkind portrait. Her reply was disarmingly heartfelt – a simple ‘no’.

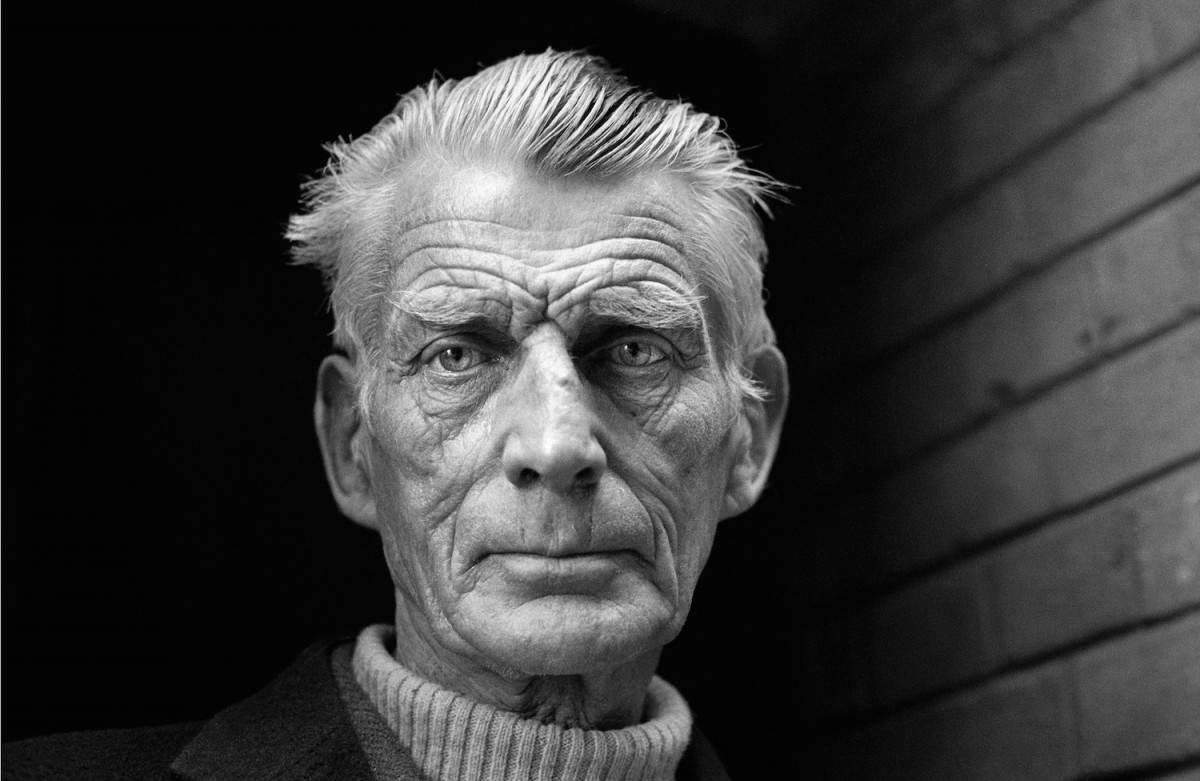

Many photographers talk of the portrait in terms of a contract with the subject, implying that the greater the rapport, the better the finished result. Jane liked it when there was a ‘spark’ with the sitter but it was by no means necessary for her to produce startling results. The famous picture of Mick Jagger laughing was taken as Jane worked around him and the interviewer with very limited time. And sometimes a rapport hindered her: the first time Jane photographed Bjork (having absolutely no idea who she was) it is obvious from the contacts that Jane had to really work at it because both of them were having too much fun – she exposed four rolls of film, always a sign that things were not ideal. The singer was almost too amenable, happy to pose and cavort as Jane circled her. ‘But in the end, I had to get her to really look at me…and I looked at her and then it was suddenly there. I didn’t do it, it was all her’. The truly iconic portrait of Bjork with her hands in front of her face is indeed the last frame on the last roll. I saw this in action on a few occasions, the moment when Jane knew instinctively that she had the picture. That was the point that she would say, ‘ah yes…there you are’, and stop. Jane’s most famous portrait is one where rapport was entirely absent. She cornered the notoriously camera-phobic Samuel Beckett in a dark alleyway down the side of the Royal Court theatre in London as he tried to evade her lens. With simmering hostility, he stood long enough for Jane to expose five frames. There may be little rapport here but the extreme directness and candour of the portrait can only be informed by a momentary flash of pure recognition between photographer and playwright.

Jane never displayed her work at home. Wherever she lived, it was relegated to a back room or outhouse, a private place with one chair where she could go and sit surrounded by her favourite images. Each shoot was remembered in detail, the room, the face, the light. She would sit among them, silent and reflective and quietly content. While she loved seeing her pictures on the pages of the Observer each week, I am convinced that it was the taking of the pictures which gave her the deepest pleasure – it was, literally, what she lived for. When she looked through a lens, in that charged moment which she always characterised in terms of love, she made the world into a place that was utterly and unmistakably her own.