The March 2009 issue of Frieze magazine had one of Keith Arnatt’s famous self-images adorning their cover, but very little else about him inside.

Given that he died just before Christmas, December 2008, I find it surprising – a bit shocking even – that there was little else about him in the magazine. The fact that I am writing this here, in a photography context, about one of the most important British and international conceptual artists of his generation indicates both the shift he made in his own career and to the blind-spots that still exist in contemporary art towards history and photography.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

I first met Keith when we were both teaching in the same photography department in the early 1990s in Farnham (then Surrey Institute of Art). When I changed jobs to University of Westminster he came to teach there for a year too on the MA Photographic Studies. So when I met Keith he was already working in photography. As Ian Walker notes, Keith was teaching practice and I was teaching theory, though we quickly realised that we were doing the same things in different ways. It also turned out, later on, that we had both bought the same little camera (a Fuji 35mm rangefinder – a small pretty and quite fast automatic camera that looked like a sardine tin). It was the camera he used to shoot the Cats and Dogs (1996-2000) series. When he showed me the small machine prints that he was working with of these images I had teased him as being the Richard Billingham of pets. They were great pictures of pets, intimate, subjective and personal. As co-curator of a show called What is a Photograph? I included them at Five Years Gallery in Shoreditch in 1998, it was the inaugural show and I believe that was the first showing of Cats and Dogs too, shown projected on to the wall from a slide carousel.

Keith Arnatt’s practice – and his teaching – was led by his thinking. Keith often read linguistic philosophy, I recall him coming in and saying he had been reading an essay by Stanley Fish (a famous American literary theorist) on being ‘against theory’. Keith was amused that a theorist was making an argument ‘against theory’ when it was clearly a theorist making the argument. This is the sort of paradox Keith enjoyed. Paradox was very important for his work, indeed he aid as much in an interview in 1997, ‘I am very fond of paradox’. It is what makes his work special and partly what gives his work what I would call its ‘serious humour’. Once, at a conference in Boston on ‘Conceptual Art’, another speaker, Eleanor Antin, a famous Californian conceptual artist based at CalArts, said to me that ‘of all the Brits’, Keith’s work was the one she liked most, because it was so full of humour and wit as well as seriousness. This combination of wit and seriousness, evident throughout his work and career (It is what was adopted – adapted – by the neo-conceptual art of the 1990s.) Conceptual art of the 1960s and 1970s in Antin’s sense and his, was about speculation, an art of questions and questioning that informed practice, teaching and theory. To put this in contemporary jargon, early conceptual art was not ‘risk averse’.

Conceptual Art

Conceptual art was, at origin, fundamentally about ideas, rather than style or any specific aesthetic regime. Thoroughly international, it was an outbreak of protest against the prevailing conventions and values of the 1960s art world, just as the then Civil Rights and Women’s Movement represented a contestation of the existing (race and gender) status quo. The critique of ‘art objects’ by conceptual artist led to a variety of responses, which included making them disappear, to ‘dematerialize’ them. Keith Arnatt’s famous early work Self Burial (1969) is a set of nine photographs of himself gradually disappearing into a hole. Here the artwork is the disappearance or dematerialization of the artist, the logical conclusion of the disappearing artwork. (The work was originally called Disappearance of the Artist.) Like many conceptual artists the use of photography to document the disappearing object, as in reportage, drew attention to photography itself as a medium of interest.

The drive towards speculation in conceptual art was why, I think, once Keith Arnatt started to use photography, he did not stick with one technique. Each work or project asks a question that moves the speculation along to another set of questions, so the look of his work changed accordingly. This is an idea of art as risk, one that might even fail. Keith was certainly not afraid of risk. Like other artists of his generation, this idea of conceptual art as speculation came from reading philosophy, which is clear in his work – quite literally.

Keith was particularly interested in ‘speech act’ theory. This theory focuses on the importance of language for mediating our understanding of the world and, in particular, certain types of utterance, which by being spoken actually define an event as an event. Language is the event, they create a ‘fact’ through an utterance. The classic example in the literature is the phrase ‘I thee wed’ spoken at a wedding (or the phrase ‘I take this woman/man to be my lawfully wedded …’). The utterance is performative, that is, it is the speech act that is not just a statement or a report, but it does something: speaking these words is – it defines – the very act of becoming married.

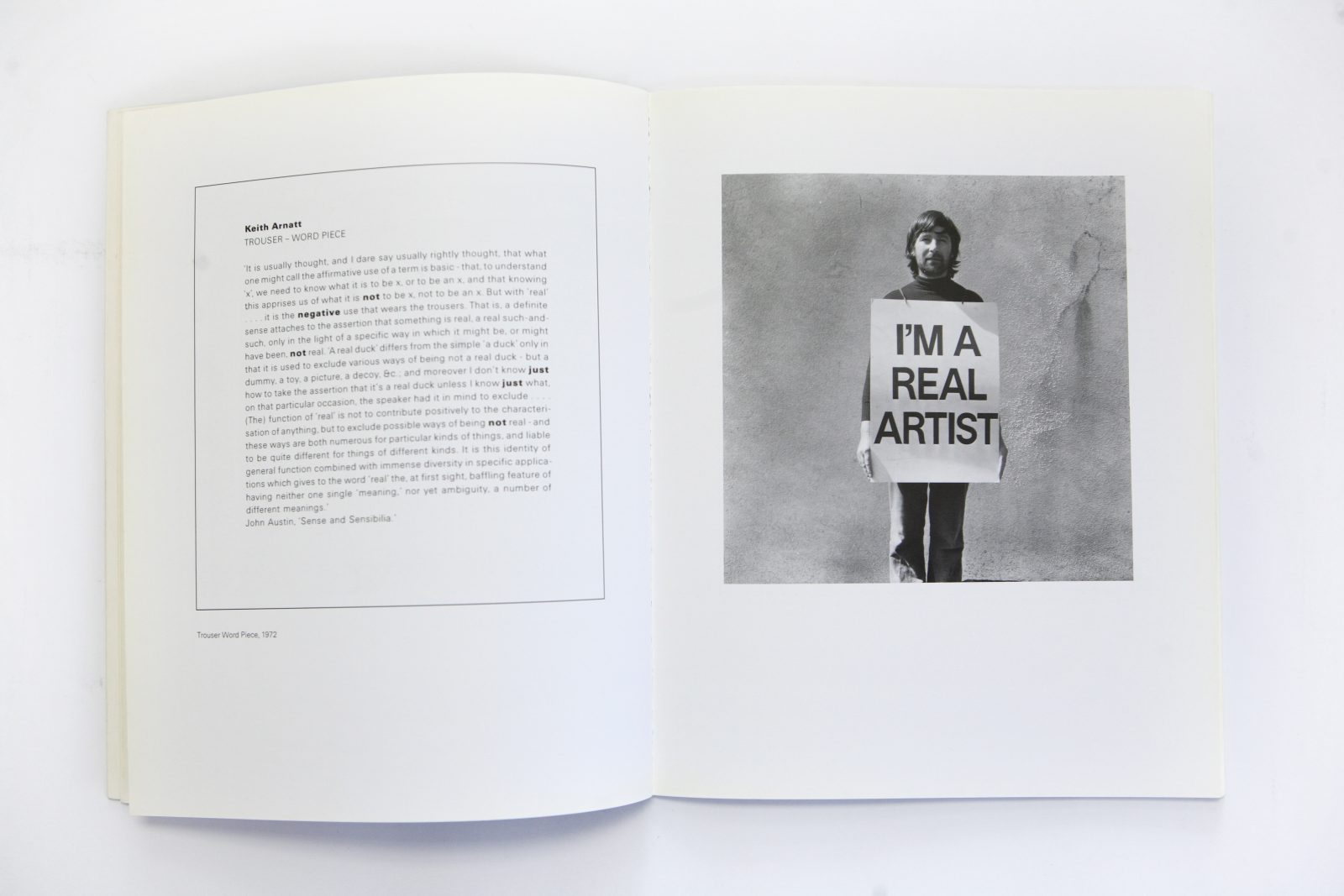

Now, Keith’s photograph and text (Trouser-Word Piece, 1972) where he is seen in the picture holding a white board that says ‘I’M A REAL ARTIST’, is a good example of his creative use of this theory. The theory itself is a text panel citing from the English philosopher, John Austin’s essay Sense and Sensibilia. In terms of the theory it raises many questions; in terms of his practice it speculates on the very notion of the artist, and indeed, the role of photography in the image of an artist and the role of the artwork in photography. Paradoxically, Keith is already an artist when he is holding this statement. So, why the need to claim that he is? The declaration ‘I’M A REAL ARTIST’ is so insistent that he is a real artist that it begs the question of why he finds it necessary to make such a claim. Does it, by the fact that he says he is an artist make him one, thus throwing suspicion that he might not be (a sort of chicken and egg logic) and what would be an ‘unreal artist’ anyway? I could go on… but the point is, his play with this type of performative linguistics is a theme throughout his work and a strategy that he returned to in his later series, Notes from Jo (1991-1994) and Notices (2001).

In all these works, and from his early work ‘speech acts’ are something that interested him. But when he took up photography as photography, he turned his attention to the idea that photography is a type of performative ‘speech act’ too, that photography is an utterance that creates an ‘event’. Although he never wrote about this specifically as a kind of theory for photography, we can see how later generations adopted it, for quite different purposes. Just as Cindy Sherman uses the media ‘languages’ of photography to create female personalities to exist as images, so, in wedding photography, the performance of the event (the marriage ceremony) creates the social proof of the status ‘married’. (Perhaps wedding pictures are today more socially important these days than the words ‘I do’ or the legal document that proves the wedding was ‘real’.) Keith’s practice hit on the key paradox of photography itself, that while it is seen as reporting on events, it also, in a way, creates events too, in their very representation. This is what interested Keith and something he learnt to do and developed, through the dominant form of photography: documentary.

It is quite clear that the street documentary work of Diane Arbus and the typologies system of the Bechers was key to his own work when he started working explicitly with photography. I think he quickly combined these methods although he used their techniques for his own quite unique aim. His early dialogues with David Hurn about photography were also key in formulating this aim too. Keith’s work uses seriality as a kind of ‘language’ of photography with which to speak, but then used this language to interrogate itself – to interrogate photography.

Rubbish

We can perhaps see this interrogation of photography most clearly in the series Pictures from a Rubbish Tip (1988-1989). The idea of making ‘art’ out of rubbish – literally – is one such delicious paradox in Keith’s work. The old famous complaint by Walter Benjamin, that photographers were ‘incapable of photographing a tenement rubbish heap without making it look beautiful’ is precisely what Keith takes up, not to reject Benjamin’s remarks, but to show – to show the viewer – that what you see depends on how it is photographed, that photography organises what it sees. As Martin Parr notes in a piece on Keith Arnatt, those pictures are simultaneously appealing and disgusting. A piece of mouldy bread looks exquisite, like a Turner landscape. This is a perfect paradox. His photograph is a document, it shows us something, but the way it shows it makes us ask or think about what photography does – at the same time that we are enjoying looking at it. This is quite an achievement, to make the viewer simultaneously enjoy what they are looking at whilst making them think about what it is, exactly: that is interesting. This is precisely his ability, to take philosophical speculation to the photograph itself. The Canned Sunsets series also play with this, the clichéd picturesque ‘sunset’, which he loves and ridicules at the same time. An interest in all the things that people discard – while aspiring art photographers despised clichés, Keith found such cliché’s of great interest.

Cats & Dogs

I recall him showing me a set of prints over coffee one day, they were end prints from his local lab, and him saying, in a phrase he used quite often: ‘I find them rather interesting’. A phrase ambiguous enough to invite you into conversation about the pictures, about what was interesting about them, yet sufficiently certain to steer you into his realm of thinking. As a photography tutor, Keith was certainly a popular teacher. One of his great abilities, was that he could talk with anyone, no matter what their practice or thoughts about photography. He would listen to what students said and make them reflect on their own thinking: what better way to teach someone: to think for themselves.

[/ms-protect-content]

Published in Photoworks Issue 12

Commissioned by Photoworks

Buy Photoworks issue 12