By Emily June Smith, 12 December 2025

“Love many things, for therein lies the true strength, and whosoever loves much performs much, and can accomplish much, and what is done in love is done well.” – Vincent Van Gogh

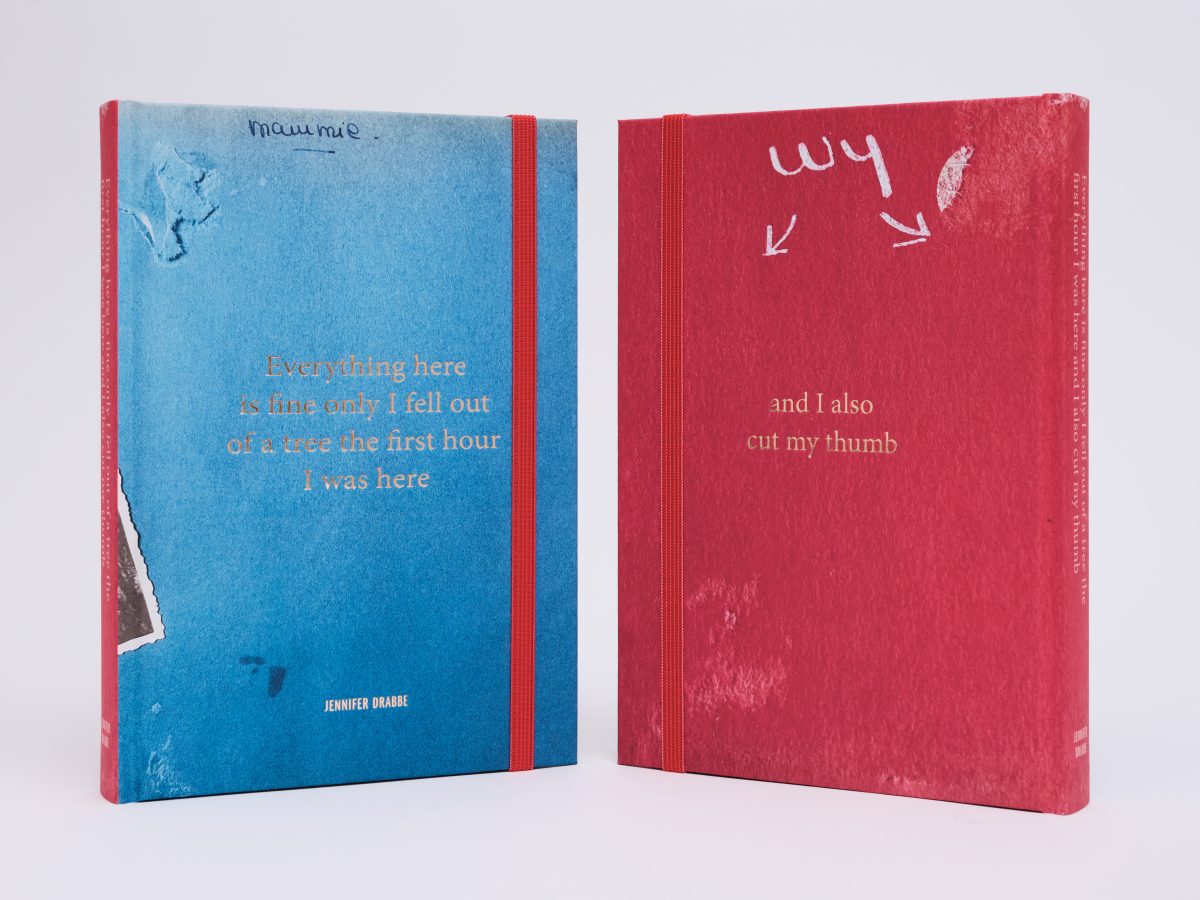

The first thing I thought of when opening ‘Everything here is fine only I fell out of a tree the first hour I was here, and I also cut my thumb’ is how much it reminds me of Van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo, an archive of raw human emotion, through generations, and connects us through thoughts and feelings.

Dutch photographer Jennifer Drabbe’s newly self-published book is an intimate, tender, and quietly powerful body of work. Rooted in family history, it draws on letters, archives and photographs to tell a story of women, connection, and love through time. We can often take our loved ones for granted. Drabbe grew up often separated from her parents, so the small daily gestures within her work become all the more powerful as you understand the longing the artist feels not only for her family, but also for connection to her past.

Like Van Gogh’s letters, Drabbe’s book is both an exploration and an act of loving through time, a dialogue carried forward and backwards, in the belief that someone will understand you. For her, the exchange happens between generations of women writing about love, the messiness of life, and worry in strikingly familiar ways.

The project began with a letter from the artist’s eighteen-year-old grandmother in 1944, who was pregnant and unmarried during the war, and unfolds through six generations, tracing an underlying sense of womanhood across time. And for me, it begins to visualise and suggest what it means to love with and through time.

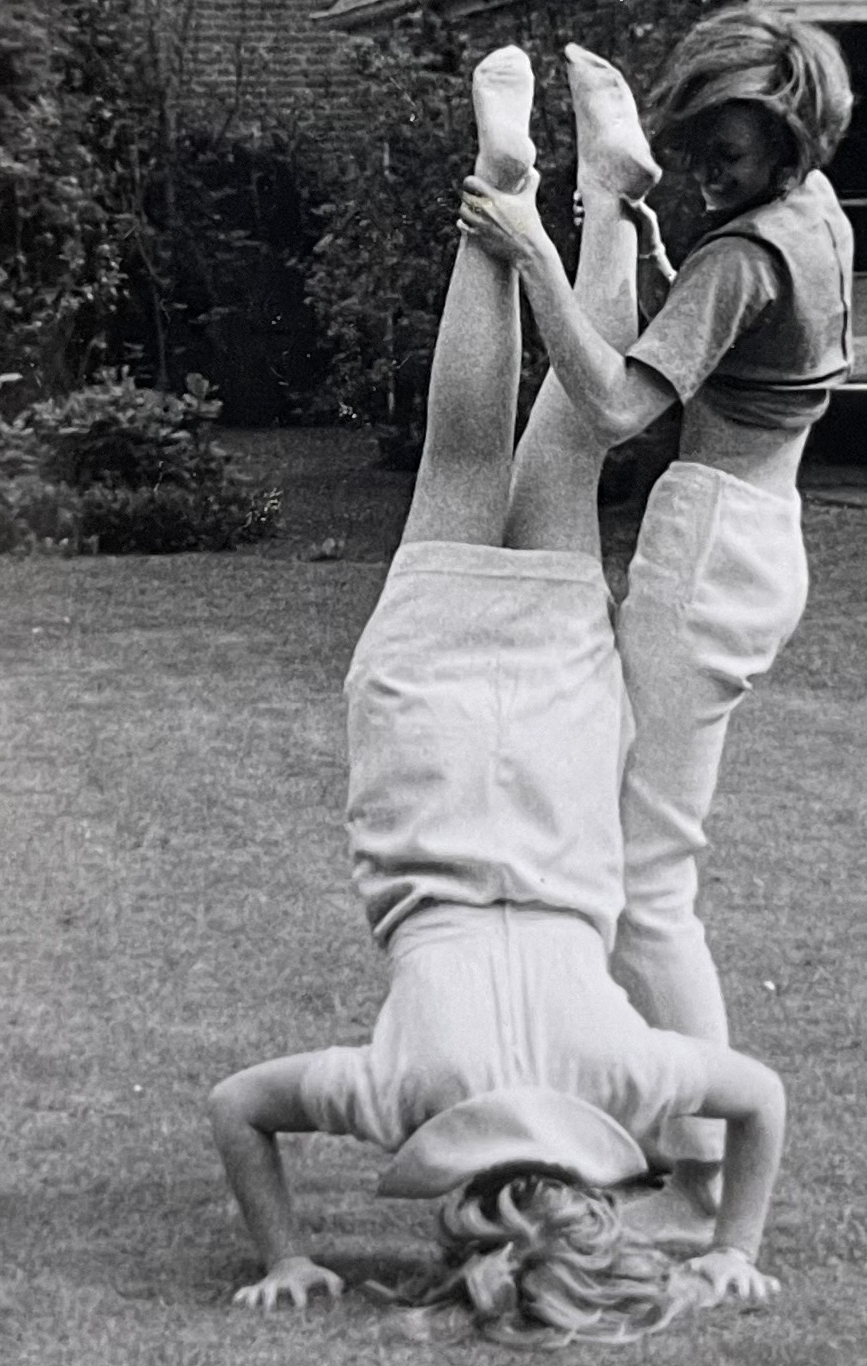

There is a power in how love is depicted throughout the time periods within the pages of the book. It begins to show us that love is not a fixed state, but a free-flowing emotion capable of travelling back and forward in time, a truth that this artist uncovers through archives, letters, and photography. She employs the visual language of everyday life and transforms it into a collective portrait of love and womanhood. In this sense, ‘Everything here is fine only I fell out of a tree the first hour I was here and I also cut my thumb’ is a tool that forces us to look back, to show us what has always been ingrained in family and is at the forefront of most of our lives: love, and the beautiful rawness of being imperfectly human.

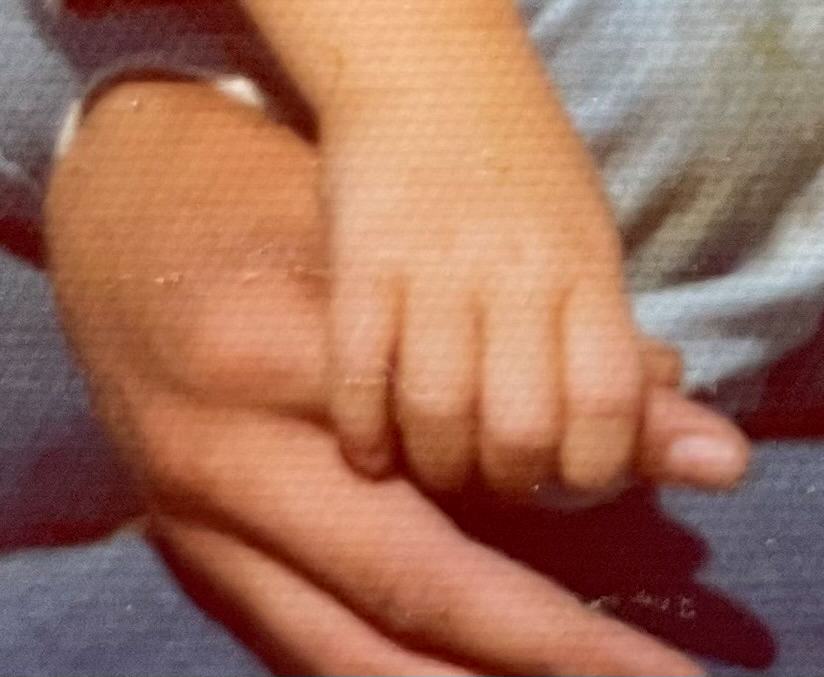

The book is both intimate and politically resonant, tracing the lives of generations of women, their loves, their worries, and their humanity. It connects the past to the present, allowing me to relate to the contemporary experience of femininity. In a world where female bodies and women themselves are so often politicised or controlled, where life is often framed as one in which men resent women, and even women turn against one another, the women in Drabbe’s book go against this notion. The fragments of bodies and embraces within the images hold a genuine sense of hope and love.

Historically, men have dominated narratives about women. However, with Drabbe’s meticulous dissection of family letters and the parts of herself she has poured into the work, the work’s intimacy and ordinariness lend it an almost political power as it transforms the personal, domestic, and emotional lives of women into something worthy of attention and care by reclaiming her family’s narrative and, in doing so, helping present women as people above all else.

Diving further into the book and looking beyond the images, you find a letter at the back titled “How I Met My 18-year-old Grandmother.” Within it, we discover that the artist and her past family not only share thoughts and feelings but also life experiences. Drabbe reflects, “How did she experience my wedding when I walked around proudly six months pregnant? No doubt she thought back to her own wedding, which was secretly arranged overnight without invitees.” Whitin the ongoing theme of femaleness presented throughout the book, her words subtly expose how societal expectations surrounding pregnancy and marriage have shifted yet still linger in the back of many women’s minds. This connection between generations links the women in the book to a broader audience of women; not only do we now see the artist’s shared connection with these people, but women viewers also share thoughts, experiences, and the pressures imposed by society through the book.

From the perspective of a viewer who feels conflicted about pregnancy, especially with the news reporting an “unprecedented decline” (BBC News, 2025) in fertility rates and the right to abortion being rolled back in parts of America, it can often feel as though women are being pressured into having children, viewed not as individuals but as a means to sustain population growth and the economy. However, Drabbe’s book, whilst quietly acknowledging these societal pressures, manages to strip away this darkness that clouds my own perspective. Through her work, she conveys the pure joy of motherhood, without explicitly stating it. Drabbe shows how normal, human, and loving it can be, regardless of one’s circumstances. Her pictures and archival materials remind us that love and resilience are enduring qualities that women have carried forward through time.

Jo Spence writes, “We are all locked into past histories of ourselves of which we are largely unaware, but by using reframing as a technique, anything can potentially be turned on its axis. Words and images can take on new and different meanings and relationships, and old ideas can be transformed.” Jo Spence: Libido Uprising, Richard Saltoun Gallery, 1–31 August 2019.

Drabbe’s work, however, takes a different approach. She does not attempt to reframe or reinterpret the past; instead, she embraces the imperfection of life as a woman, holding the past with love and laying it bare, and intertwining it with her own narrative. She demonstrates that the power of her work lies not in altering histories but in attending to them with intimacy, care and acceptance.

The book can be described as perfectly imperfect. Designed to resemble an old diary, the addition of the elastic ring around it, reminiscent of those found on many notebooks, adds a charming touch. At the back, the book holds the letter “How I Met My 18-year-old Grandmother,” tucked inside an envelope you might find in your own kitchen, opened by a loved one. It’s a beautiful nod to the domestic and the mundane. The scattered archival images throughout the book evoke the feeling of a personal family archive from before the digital age. At the same time, the artist’s own photographs blend seamlessly with them, much like how we hold memories in our minds, mixed with our own life experiences; we often relate to them together, telling a story of what it means to love through time.

The book encompasses the people’s pictures through its depiction of women as individuals, not as mere objects. It unites women across history through the generations of women in Drabbe’s life, pushing the narrative that love, life, and people will never be perfect. That imperfection is the beautifully perfect part of living, of being human.

Emily June Smith is a neurodivergent visual artist based in Romford whose work extends documentary photography into explorations of personal identity and social experience. Drawing on her lived reality as an artist with neurological disabilities, she creates nuanced, empathetic images that challenge dominant narratives and foreground underrepresented voices. Her practice is shaped by a commitment to visibility, understanding, and empowering others to embrace their differences. Smith is a founding member of the Zinnia Collective and is currently part of an artist development programme with Autograph. She also works as a freelance artist facilitator and Digital Youth Engagement Producer for Photoworks.

Jennifer Drabbe is a left-handed redhead, as well as a visual artist and former theatre director. Most recently, she self-published two remarkably personal books. With a laser focus on small, intimate and daily detail, she closely observes her direct family and their tender and playful behaviour, looking for traits that make us so human. Both books are part of the Rijksmuseum’s collection in Amsterdam. Drabbe’s work has been exhibited in various Amsterdam venues, including NDSM-Fuse, the Amsterdam Museum, and the Amsterdam North Museum. Her work is also included in the monumental photo book Pools (Rizzoli), curated by Lou Stoppard.