From issue: #23 Seen/Unseen

In the middle of the country, about 100 miles from London, Birmingham is the second largest city in the UK. Like the UK’s other big cities, it boasts a rich multicultural mix, including some 30% of the population who identify as Muslim. But Mahtab Hussain, who grew up in Birmingham, says being Muslim was something that only came into focus over time.

‘A pivotal moment was the Salman Rushdie affair in 1989 [in which the author was put under a fatwa for his novel The Satanic Verses],’ he says. ‘From then on I was Muslim, not Pakistani, and what was foregrounded was the religious space. In the 1990s films such as True Lies and even Die Hard were so racist, and in 2003 the Iraq War was even more televised. This idea of the Muslim Arab being the enemy started to filter in.’

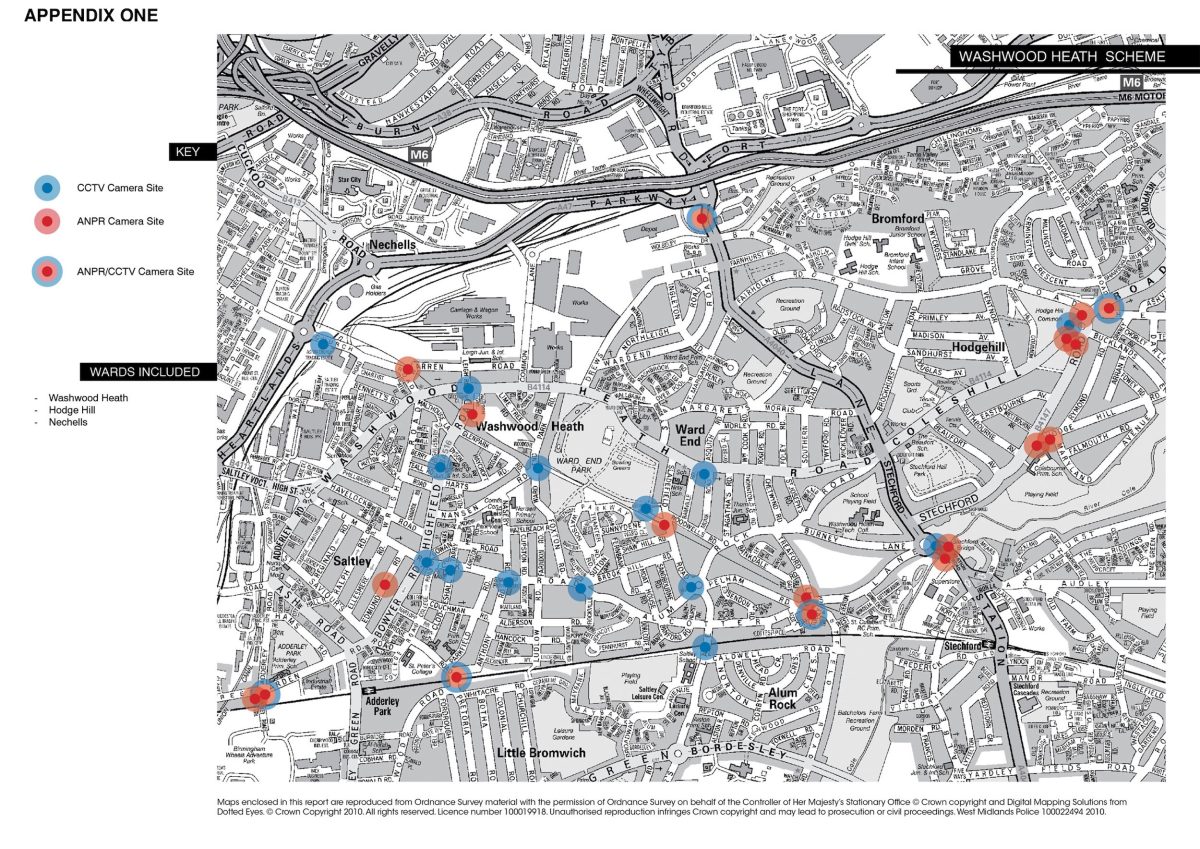

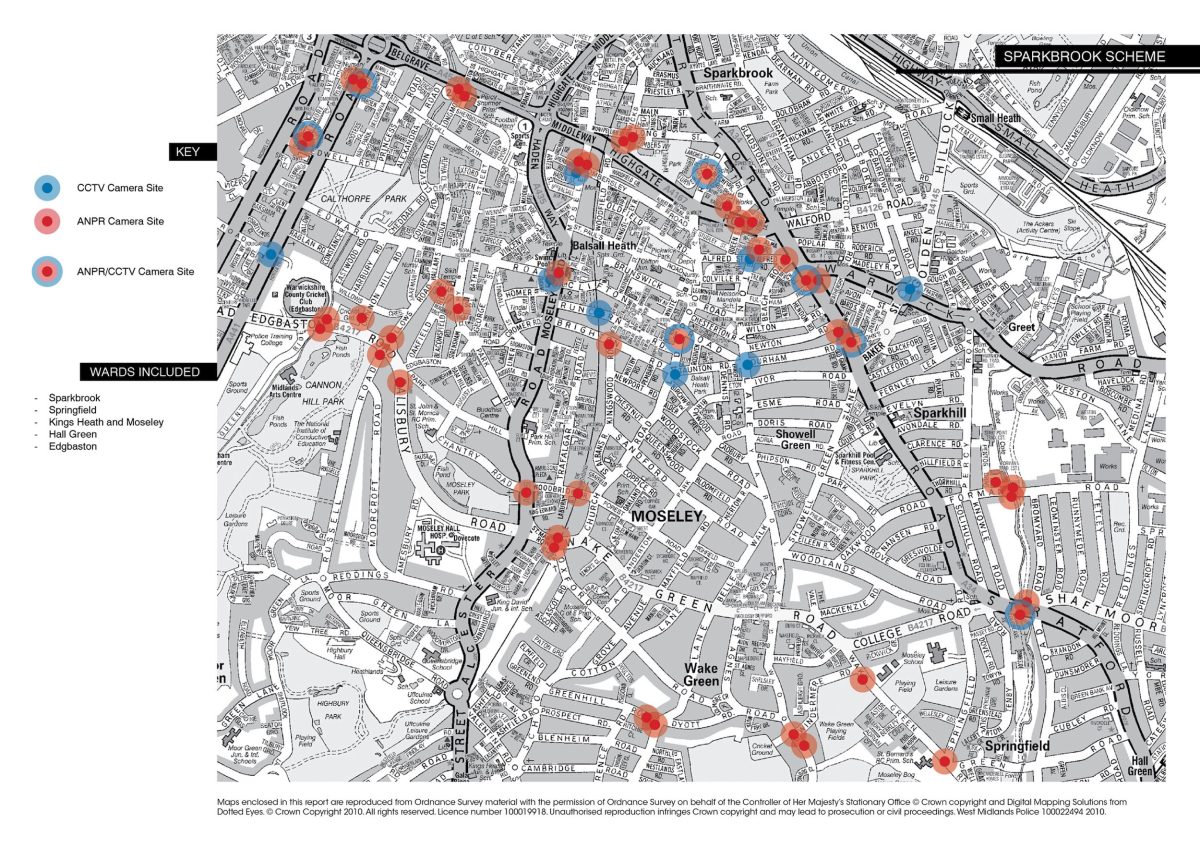

In 2010 the impact that these stereotypes were having on the local community became clear, when West Midlands Police and Birmingham city council were forced to apologise over a network of cameras installed in two predominantly Muslim neighbourhoods. Dubbed Project Champion, this initiative aimed to monitor Sparkbrook and Washwood Heath with 108 automatic number plate recognition cameras, 36 CCTV cameras, and 72 spy cameras – 216 cameras in total, three times more than in the city centre.

The cameras, which included covert devices secretly installed in the street, made it impossible for residents to enter or leave these neighbourhoods without their cars being tracked, and the data they captured was to be stored for two years. There was no formal consultation over the scheme, and the few local councillors who were briefed later said they been misled into believing it was there to tackle antisocial behaviour, drug dealing, and vehicle crime. In fact the £3.5m project had been paid for by the Terrorism and Allied Matters fund, and was a counterterrorism initiative based on racial profiling.

Suspect surveillance

A local activist called Steve Jolly helped expose the surveillance and, after a campaign by The Guardian, angry public meetings took place. The Labour MP for Birmingham’s Hall Green constituency, Roger Godsiff, asked Parliament to denounce Project Champion as a “grave infringement of civil liberties”, and West Midlands police and Birmingham city council were forced to abandon the scheme. Apologising in a joint statement for not being ‘more explicit’ about the project’s funding, they conceded their actions might have ‘undermined public confidence’.

It’s an understatement that borders on the absurd but, says Hussain, ‘Anyway no one trusts the police’. ‘If you are black or brown [in the UK] you always experience the police with a degree of violence,’ he explains. ‘Even me in London, I could be with a group of friends but it will be me who is targeted. That experience is very real.’

In his new work-in-progress, What Did You Want To See?, a Photoworks commission in partnership with Ikon Gallery, Hussain is exploring the impact of Project Champion had on Birmingham’s Muslim community. His exhibition, on show at Ikon from 20 March t0 1 June 2025, will include several separate but interconnected spaces. One will include single, group, and family photographic portraits plus individual narratives, made by Hussain since 2010; the images will be on display within a prayer room, which will also feature a video of five prayer sequences that visitors can watch or join.

A second room will be set up as a surveillance hub, with 220 CCTV cameras installed around an olive tree – visitors put on edge by being watched, but welcomed in under the branches. Two other videos will delve into the Everyday Muslim Heritage & Archive Initiative held by Northumbria University, celebrating sport, community activities, and social gatherings, plus Hussain’s own experience of growing up in Birmingham, alongside archive material surrounding the surveillance debate.

New work

Hussain is still making new work for the show, and says his approach to the portraits is informed by seeing the surveillance cameras while working on a previous project, You Get Me?, published by MACK Books in 2017. ‘I was photographing young men in Birmingham one summer and looking up at the cameras,’ he explains. ‘They were positioned quite high, so I was getting the sun in my eyes, and putting my hand up for shade.

‘For this project I have been thinking about how to show people without showing them, so I want to include people looking up with their hands over their faces, create work from that perspective,’ he adds. ‘I also want to isolate people from their environment using coloured backgrounds. In the past I’ve worked with a lot of environmental portraiture, so this time I want to be playful. But I also want to make the point that this surveillance was not just one community in Birmingham. We are all part of surveillance culture now.’

Both tactics point to a certain irony – or difficulty – in what Hussain is doing, making work on how cameras have infringed people’s rights, while using the medium of photography. But while he agrees that this is particularly relevant here, he says it’s always a concern. Photography is wrapped up with a whole language and world view of colonialism, he points out, in which certain races are considered lesser humans. Because of this, he avoids expressions such as ‘shooting’ or ‘taking’ a picture, and describes those he works with as ‘sitters’ rather than ‘subjects’.

‘I speak with everyone I work with one-to-one, and try to express my own vulnerabilities and our shared experiences,’ he says. ‘I do interviews, I use consent forms, I give people photographs or books afterwards. I never want to make something hard, I want to make something they would be happy to have on their wall. I want to make work that contains beauty and lightness.’

Reclaiming language

It’s a challenge to try to make work that has nuance and goes beyond the stereotypes, but he feels compelled to attempt it. The Muslim community in the West has felt downtrodden, invisible, or even demonised, he points out; when he opened his recent exhibition on Muslims in Syracuse, USA, visitors cried because they finally felt sympathetically seen (part of a wider, ongoing project on Muslims in the US, it was on show from February – March 2024 at ArtRage Norton Putter Gallery).

‘Sometimes I wonder what kind of work I would make if I wasn’t part of this community,’ he says. ‘But still I feel I have to try. Racism has directly affected four generations of my family now, even my little girl at ten years old. If I don’t make work engaging with our experience, what am I doing? Photography is a very powerful medium, and the most popular, so I feel I am fighting fire with fire. I want to use that language, to say “Let’s take ownership of our own image”.

‘And I can see it is having an effect,’ he continues. ‘I have been commissioned to make a work about the 2.5 million soldiers from India (Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh) who fought in World War Two, which will be seen by two million people on TV and on the Royal Festival Hall [a major cultural centre in London]. I am also creating a bronze miniature which we hope might be made into a permanent sculpture. How beautiful to be able to do that.’