Lucy Rogers, 24 October 2025

After my grandmother’s house was left abandoned in the early 2010s, I would regularly visit with a camera, hoping to capture something of the strange feeling which the space had come to encompass. Even at the time, I was struck by how disassociated the photographs felt from the many memories and stories I had for so long connected with this particular place and with my grandmother. It felt as though a thread was missing, an important tie between the past and my memory of her in the present, which was already changing. Personal items of my grandmother’s, now no longer touched or cared for, began to slowly transform into artefacts and relics from a previous time.

In an ongoing series of interrelated works titled Erased (2021–), artist and photographer Leslie Hakim-Dowek examines the sudden gap in memory and knowledge which appeared after the passing of her mother in 2019. Prompted by the intense realisation that her mother’s (hi)story (as well as her own) had already been forgotten, Erased (2021–) explores how memories are lost, as well as passed down through generations, changing and shifting over time. When I spoke to Hakim-Dowek in September and asked what motivated her to make the work, she described how she became acutely aware of how quickly the memory of her mother appeared to be dissolving. “Even after a few weeks, her name was no longer mentioned, even by close family”. Feeling left without a period in which to mourn and remember her mother, Hakim-Dowek turned to photographs found in family albums but soon realised that these too recalled a practice which has – in today’s rapidly-changing and image-saturated world – become forgotten and outmoded. As she explained, “we used to have photo albums, which were like a family ritual where people would sit, reminisce, and tell stories, but I realised that a lot of my mother’s photographs would never be activated because no gaze would fall upon them.” This prompted the first iteration of Erased (2021), a series of photographs in which Hakim-Dowek removed all evidence of her mother, in what she describes as an “anticipation of forgetting”. Laid out in a timeline and using captions as the only indicator of any tie to a specific time and place, the series follows her mother’s life, from Tiberias, Palestine, where she was born in 1925, to her many years spent living in Beirut, Lebanon, until her passing in London, England in 2019.

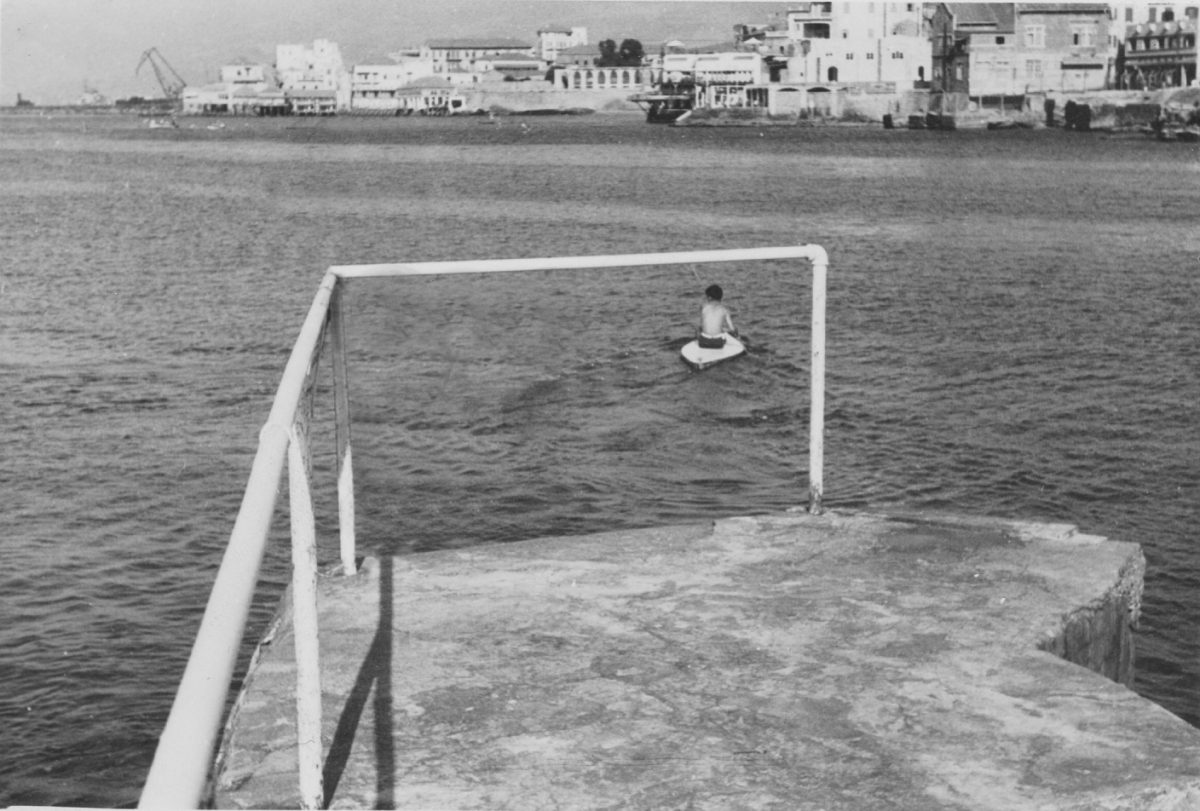

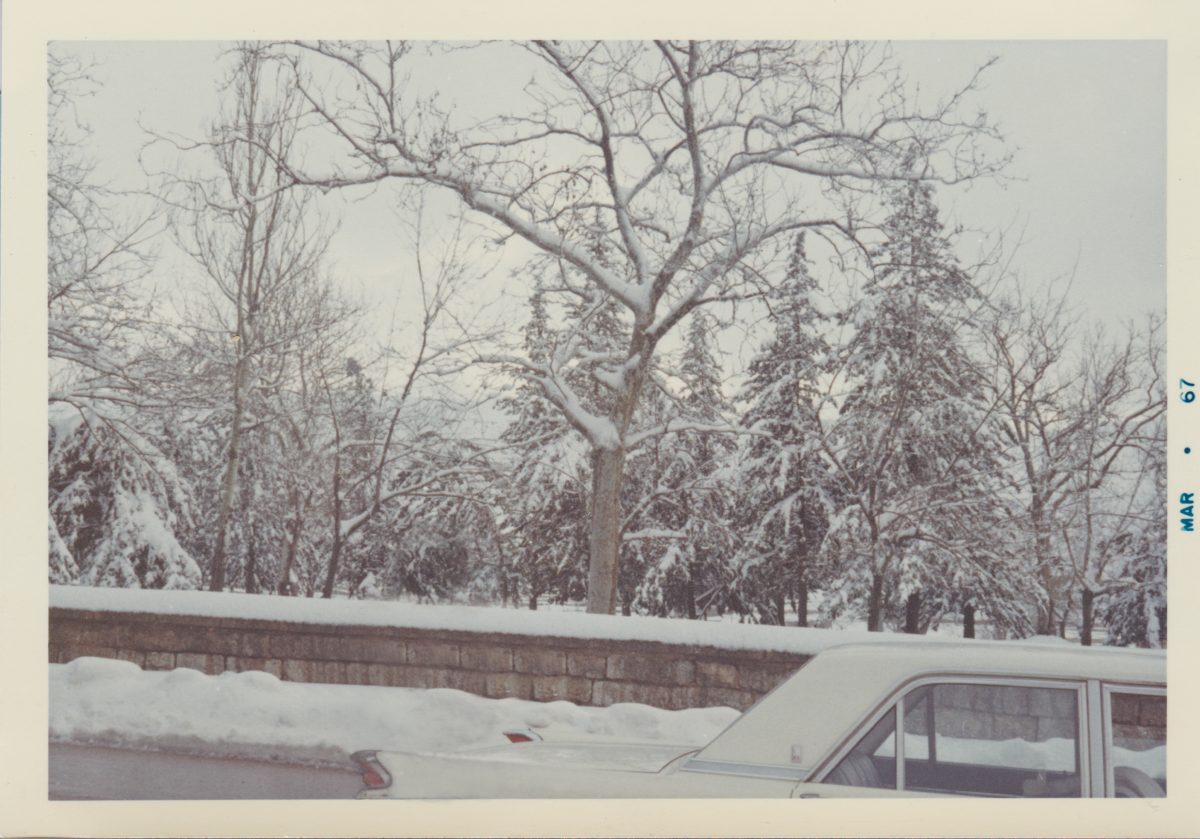

By creating empty scenes from photographs taken on day trips and family holidays, Erased (2021) recalls a time when photography was reserved for remembering special occasions. Yet in a chronology spanning almost 100 years, Hakim-Dowek’s erasure of the subject leaves the images both disconnected from time and disjoined from one another. Only the subtle shift in colour palette, which moves from early black-and-white to the nostalgic glow of colour film, betrays any hidden sense of duration. In viewing Erased (2021), we are reminded of the body as an important carrier of meaning and signifier of time and continuity, for without its ageing presence, each image is rendered timeless and disconnected. By bringing our attention to the background, Erased (2021) functions like a collection of still photographs of sets taken from an unknown film. Without further information, the photographs can only point to a narrative which is impossible to decipher and a life about which little can ultimately be known.

Hakim-Dowek compares this sense of fragmentation to her own experience of being “set adrift” after the loss of her mother. Born in Beirut, Hakim-Dowek left Lebanon at the beginning of the civil war in 1975. She describes her mother as a “bridge”, connecting her to her own roots and history, through a specific geography. Her mother, who came from one of the many minority groups of the Middle East, lived through numerous conflicts and was consequently displaced multiple times. It is, a story, which like so many of the hidden histories of the Middle East has been forgotten, lost or blotted out. With each new place, her mother was forced to learn a new language and assimilate herself within a new culture. “In the Middle East, every generation of the family has had to move. Families are dispersed, so you get this disconnect between generations”. Reoccurring conflicts, political unrest, as well as the systemic erasure of minority histories, has left few surviving traces. Without “sites of memory” for shared remembrance, it becomes difficult to bring visibility and acknowledgement to the many complex and intersecting histories and lived experiences of people from the region, adding to their erasure over time.

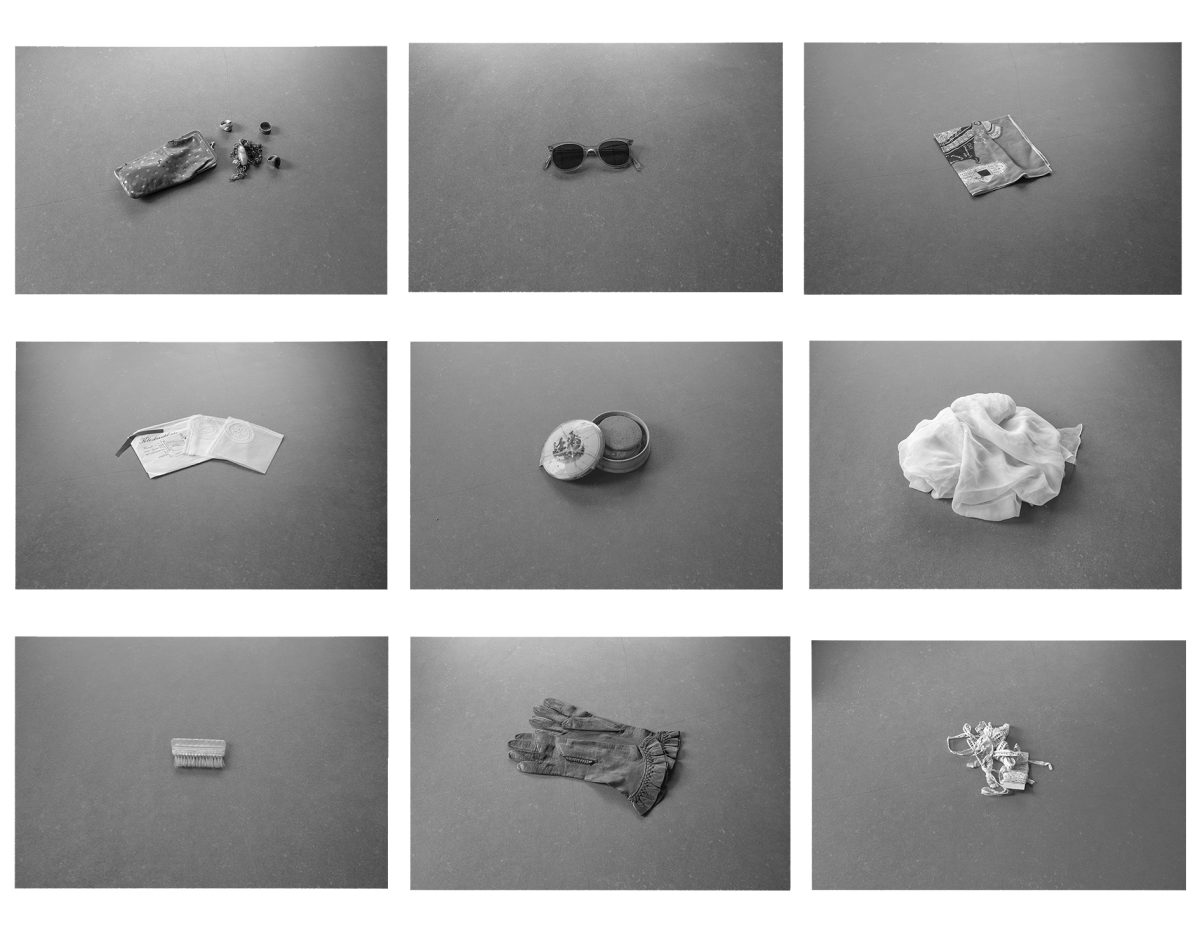

Without a museum or archive in which to preserve something of the (hi)story of her mother’s community, in a second iteration titled Index of Objects, Hakim-Dowek sets out to create a repository of her own, through carefully photographing and cataloguing her mother’s belongings. Viewed individually, each delicately photographed item forms a “mini site of memory” which while tied to her mother’s life, also gestures towards a complicated, shared generational history. Some of the objects carry associations, also for the artist herself – such as a powder pot which once belonged to her grandmother, who came from Smyrna (modern-day İzmir). However, among the objects are also those which are untouched or unused (“still in their original packaging”), as well as items that are damaged beyond repair and “wouldn’t have been any use to anyone”. Initially surprised by the sheer number of items, Hakim-Dowek describes how she suspects a “dormant fear of losing everything” may have motivated her mother to keep all her belongings. This was, after all, not irrational but had “happened, many times before”. As Hakim-Dowek explains “Between the objects there is this huge anxiety of keeping absolutely everything you own, because you don’t know what tomorrow will bring”.

Looking closely, Index of Objects also speaks to another intimate history, which the artist describes as a parallel “Index of Femininity”. Combs, hair pieces and elegant evening wear such as gloves and hair pins, all suggest a performance of femininity which is historically specific but also symbolic of social and cultural exceptions determined by class as well as gender. As Hakim-Dowek explains “being a woman at that time, you were not expected to work as that would mean that your husband did not earn enough”. As such, many of the items are symbolic of status, while also gesturing towards hidden memories, dreams, and aspirations. In selecting a range of diverse items (and photographing them on equal terms against a neutral background), Hakim-Dowek also resists a depiction of her “mother” as foremost maternal, preferring instead to examine her mother’s identity in all its complexity and across the many stages of her life. Like Erased (2021), Index of Objects is marked by a sense of unknowing, of being unable to grasp or construct a complete or accurate picture.

Lucy Rogers is a writer, artist and researcher, based in the UK. Lucy recently completed doctoral research with CREAM (Centre for Research in Arts and Education and Media) at the University of Westminster, where she was the recipient of a AHRC scholarship. Her long-term research focuses on the archive of the photographer, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg and in 2023, Lucy curated the exhibition, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg: Memoryscapes with the Large Glass gallery, London. Lucy has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards for both her academic research and own photography practice. She is also a contributor to the photography platform, C4 Journal.

Leslie Hakim-Dowek is a visual artist of Lebanese origin based in London. War and wilderness are the over-arching themes in her practice as stories of warfare and the continued abuse of our environment both stem from man’s struggle to control, tame and own the wilderness. In relation to her homeland, her practice often focuses on issues of identity, migration and memory combining photography, archival material and creative writing. She is a Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Portsmouth and undertakes academic projects mostly related to Memory Studies as well the legacy of conflicts and hidden histories of the Middle East. This follows on from the AHRC Ottoman Pasts, Present Cities: Cosmopolitanism and Transcultural Memories conference project she helped to organise at Birkbeck College and for which she curated the exhibition East and West: Visualising the Ottoman City. She has widely exhibited in the UK and abroad and her work is in many private and public collections.