From issue: #25 Multiplication

Diane Smyth, 06 December 2024

Photographs reify, taking small scenes from the space/time continuum, and putting them inside a frame and behind a fourth wall. This process has been likened to commodification but, wonders Photoworks’ 20204 Annual, what happens when those images are mass produced? Diane Smyth, editor of Annual #31 Multi Multi, investigates.

In 1826 Nicéphore Niépce fixed the first image captured with a camera; in 1839 his associate Louis Daguerre presented the daguerreotype process to Paris’s Chamber of Peers. Requiring a sheet of silver-plated copper, the daguerreotype could be exposed in a few seconds, fixed and sealed. But it was also a one-off, creating unique images on silvery surfaces, something akin to frozen mirrors. The ability to create multiples was developed separately by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1830s experiments with salt prints and calotypes.

Literally named a calo [beautiful] + typos [impression, pressing, or model], this process was designed to facilitate reproduction. For Michelle Henning, its development stemmed from the socio-economic environment in which Fox Talbot was working. “Many of the early experiments aimed to multiply images for industrial purposes, making possible repeat patterns or the mass-production of identical images,” she points out in Photography: The Unfettered Image.1 Later she adds: “Photographic reproduction of artworks and the mass reproduction of photographic images in books only became possible in the very specific conditions of the late 19th century and early 20th century. It was, above all, dependent on an industrial, capitalist and imperial economy with its global trade in materials, artefacts and human labour.”2

Working in the forge of industrial capitalism, at the centre of a global empire, Fox Talbot (and his peers) had created a process which furthered its workings. Consumer products started to be mass-produced, and identical images helped brand and promote them; Britain’s influence spread around the globe, cemented and enforced by images. But photography wasn’t just a useful tool. In creating multiple images it also reflected industrial capitalism on a conceptual level. As Kate Crawford observes in Atlas of AI: “From the lineage of the mechanised factory, a model emerges that values increased conformity, standardisation and interoperability – for products, processes and humans alike.”3

Mechanical Reproduction

The seminal essay on image replication is Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, and it points to similarities between the economic structure of capitalist society, and its culture and technology. In particular, he suggests a link between the way commodities function and a certain perception of images (and the world). Benjamin writes that “the feeling of strangeness that overcomes the actor before the camera…is basically of the same kind as the estrangement felt before one’s own image in the mirror”,4 referencing photography’s ability to detach what it shows, just as commodities are detached from their production.

And he adds: “But now the reflected image has become separable, transportable,”5 suggesting that what is reified can be put into motion. In the same essay, he references a “sense of the universal equality of things”6, the feeling that once reified, commodities are interchangeable. Benjamin draws on Karl Marx’s writing here, the idea that, once divorced from their production and use, commodities can be quantified and exchanged. “When I state that coats or boots stand in a relation to linen, because it is the universal incarnation of abstract human labour, the absurdity of the statement is self-evident,” writes Marx.

“Nevertheless, when the producers of coats and boots compare these articles with linen, or, what is the same thing, with gold or silver, as the universal equivalent, they express the relation between their own private labour and the collective labour of society in the same absurd form.”7

Closely related to exchangeability is fungibility, in which one thing can function as another; coins symbolise the same thing and are therefore interchangeable, though no two coins are exactly alike. The physical forms represent an ideal, which is unrealisable but allows these representations to work. It’s a kind of platonic understanding of the world and, as this reference suggests, relies on a metaphysics that predates capitalism; even language would be impossible without generalising from real-world examples, without extrapolating a ‘circle’ or ‘dog’ from many particular instances.

But moving from agrarian to market economies demanded a consciousness in which this understanding expanded, so that commodities could be fungible and exchangeable. Benjamin, writing in 1930s Germany, suggested that images and their reproduction were linked with these shifts, noting: “The transformation of the superstructure, which takes place far more slowly than that of the substructure, has taken more than half a century to manifest in all areas of culture the change in the conditions of production.”8

Of course exact multiples can’t be achieved, and in one sense this doesn’t matter – in order to be fungible, commodities don’t have to be literally identical; they just have to be able to stand in for each other. But in offering a depiction of replication, multiple images suggest the fantasy or desire it can happen.

Types and ideals

In ‘The Precession of Simulacra,’ Jean Baudrillard describes the Native American “in the glass coffin of the virgin forest”9, the model of all possible Native Americans from before ethnology, a metaphor that evokes both Snow White and box-fresh commodities. A similar process recurs elsewhere. The first Great Exhibition, held in 1851 in London’s Crystal Palace, was read as a miniature of the wider world, gathering commodities from the newly colonised globe and claiming, “in part, to be presenting a total representation of the world, a copy placed at a distance from the original”10, writes Andrew H. Miller.

Types and multiples also underpin taxonomies in natural sciences, in which individuals are iterations of a species; in natural history museums, single specimens read as examples or models. Born with modern Western science in the 17th century, taxonomies went into overdrive in the 19th and early 20th century in racial stereotypes and hierarchies, and photographs were used to help build social and racial types, which wrestled the vast variation of the world down into stock characters. “The early promise of photography had faded in the face of a massive and chaotic archive of images. The problem of classification was paramount,” writes Allan Sekula in The Body and the Archive.11 Earlier he notes: “This interpretative process required that distinctive individual features be read in conformity to type.”12

Taxonomies, images, and commodities united in the 19th century under the umbrella of multiples; they even united in one individual, Charles Darwin, who was part of the Wedgwood family as well as a biologist. Wedgwood pioneered mass-producing crockery and transfer-printing images onto it; Darwin’s scientific work has been associated with social Darwinism and, though his support of it is moot, his cousin, Francis Galton, developed the theory of eugenics. Galton used composite images to find and reinforce ‘types’, which were spread around the world via networks of newspapers, telegraphs and trains.

Not so peripheral

This brief introduction suggests that the ability to create multiples is key to 19th-century industrial capitalism and the mass societies which followed. Yet multiples in photography have been little explored. Benjamin’s essay aside, writing on photography has often considered individual images as if they are unique, like so many daguerreotypes, and as if their duplication and circulation are somehow peripheral. Reproduction has even been deliberately suppressed via artificially limited editions.

That is, until recently. Digital images and online networks have shown that reproduction and circulation are far from peripheral, and have prompted renewed interest in both. The Centre for the Study of the Networked Image at London South Bank University was set up a decade ago; in 2009, Hito Steyerl published her celebrated essay, ‘In Defense of the Poor Image,’ considering digital images and “their acceleration and circulation within the vicious cycles of audiovisual capitalism”.13

In 2022, Michelle Henning published her book on image reproduction and circulation, Photography: The Unfettered Image, and ventured: “Instead of conceiving of the mobility of the photographic image as a negative quality, we might think of it as a quality that is particularly interesting from the perspective of the present moment in which media are multiplying and increasingly mobile, pervasive, even invasive.”14

More recently, AI imaging has renewed questions around how photographs represent the world and what we can understand from them. AI works with datasets, using taxonomies to allow computers to ‘read’ and generate composites. As Crawford writes in Atlas of AI, that process suggests ways of conceiving of data that facilitate “stripping of context, meaning and specificity”15 and, if this process has been with photography from the start, it’s fair to say it’s accelerated.

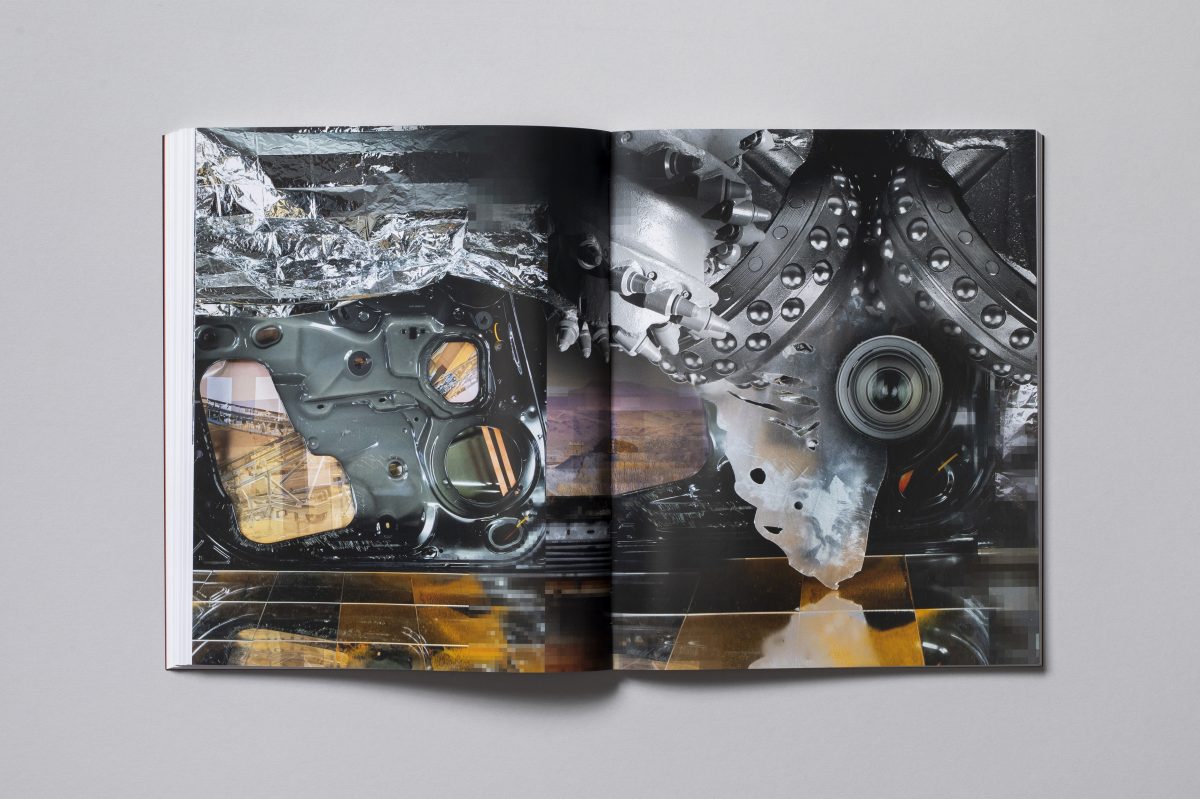

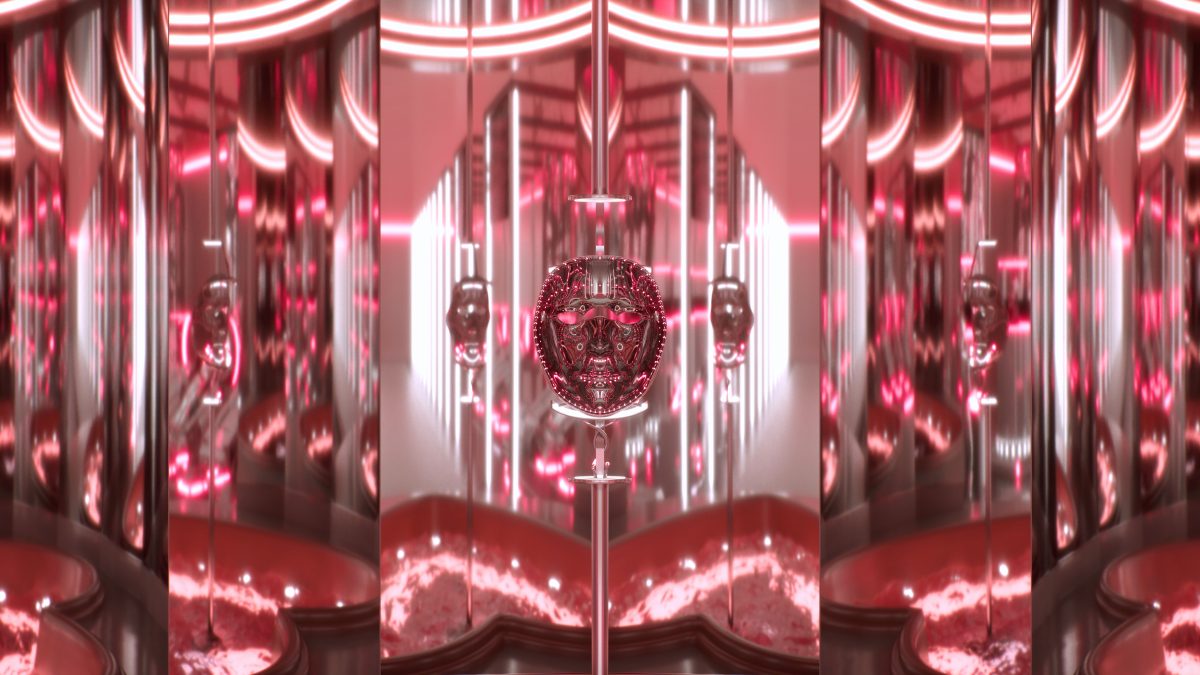

The artists gathered in Photoworks Annual #31 Multi Multi are working with multiples and (nearly all) showing work from the last decade; some use photographic multiples, some work with types, some use photographs to talk about multiples in our society. GERIKO’s project for Juno Calypso’s The Salon, 2018, uses doubling, unblemished metal androids and a mask to explore beauty ideals, for example; Yuxing Chen’s The Oriental Scene, 2021-ongoing, uses postcard images and replica models to explore Western imperialist “chinoiserie” Other artists explore new technology.

Marcel Top’s Sara Hodges, 2021, creates a dataset of the ‘perfect’ American using images shared online by ‘patriots’, while Armin Linke and Estelle Blaschke’s Image Capital, 2022-2024, considers photography’s role in standardisation, observing organisations using images to classify plants and animals.

Multi Multi also suggests ways to rehabilitate photography, with projects that emphasise the imperfect and the individual over the repeatable. Ton Grote’s Eindhovenseweg 56, 2022, is a kind of ‘anti catalogue’, showing consumer items at the end of their lives, not their idealised, box-fresh birth; Raena Abella’s Faces of Grief, 2021, uses an unpredictable early analogue process to make multiples which are not exactly alike. In Sporenland, 2018, Sugawara shows the progress of water and mould across early glass-plate negatives, suggesting the acceptance of impermanence and patina over seeking a perfect “ideal”.

Map and Territory

In ‘The Precession of Simulacra’ Baudrillard writes about maps, territory and the relationship between the two, drawing on Jorge Luis Borges’s On Exactitude in Science and the idea of a 1:1 map. If everything is individual, unrepeatable, and constantly changing, this concept suggests, then the only way to truly orientate is to use the world itself. Lewis Carroll, the 19th-century British mathematician, author and amateur photographer, also suggests this understanding in his 1893 novel Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, which also includes a life-size map. “It has never been spread out, yet,” says a character discussing it. “The farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country and shut out the sunlight! So we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well.”16

Carroll is right, of course, the only way to really see the world is to see the world; and as a documentary, indexical medium, photography has the ability to do just that. The fact that it “cannot signify (aim at a generality) except by assuming a mask”, as Roland Barthes writes 17 “…involves photography in the vast disorder of objects – of all the objects in the world.”18 Barthes seems to suggest this is a failing, but perhaps it is also a strength; emphasising the particular and the individual, images show a kind of sublime. They show that each thing is specific, and the world therefore beyond our ability to represent.

In 2011 Erik Kessels printed out 350,000 images uploaded in a single day in 24Hrs in Photos; heaping the photographs up in huge piles, Kessels framed this installation in terms of image overload. Thirteen years later perhaps it reads differently, helping us conceive of “the vast disorder of objects”19 and the peculiarity of reading distinctive individual features “in conformity to type”.20 Evoking a sheer plurality of views, ‘image overload’ undermines received perspectives – the viewpoints which dominated for so long, which were held by the powerful men wielding the cameras. As such it’s a kind of iconoclasm.

Iconoclasm

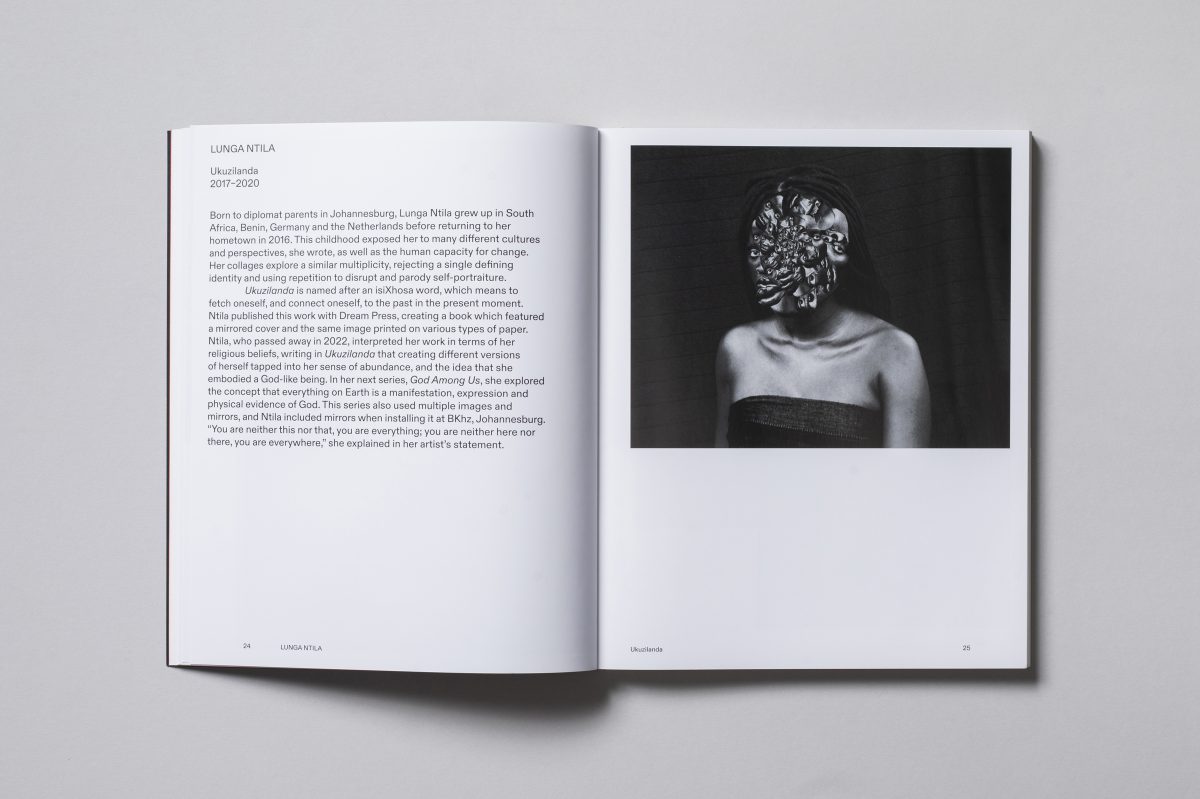

Iconoclasm in 16th-century Europe reflected and helped usher in a new era in which the market, not the church, held power; intriguingly, religious belief also flickers through Multi Multi, framed as a way to resist commodification. Lunga Ntila used multiples to say a single portrait couldn’t represent her, because her existence was an expression of God and therefore the universe; Raena Abella created multiple images of a religious icon, commenting on both the expansiveness of her belief and the colonisation which imposed Christianity on the Philippines.

On the other hand, the anonymous Iranian protestors Hoda Afshar highlights in Women Life Freedom, 2022, push back against a religious regime, using repeated gestures to speak out as one; perhaps humans can’t help but generalise, and creating alternative types can challenge norms. Either way, whether by focusing on the particular, or creating a new set of conventions, photography can disrupt established taxonomies. But doing so requires greater awareness of its role in society, including its reproduction and circulation.

This article is an abridged version of the introduction to Multi Multi Photoworks Annual #31

1 Henning, M., 2018. Photography: The Unfettered Image. Routledge. p47 2 Henning, M., 2018. Photography: The Unfettered Image. Routledge. p64 3 Crawford, K., Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press. p56 4 Benjamin, W., 1969. ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,’ translated by Harry Zohn from the 1935 essay. In Illuminations, Hannah Arendt, ed. Schocken Books. P11 5 ibid 6 ibid. p5 7 Marx, K., 1867. ‘The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Thereof,’ translated by Bert Schulz (1993). In Capital, Vol. 1, Part I: Commodities and Money, Chapter I: Commodities. p4 8 Benjamin, W., ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,’ translated by Harry Zohn from the 1935 essay. In Illuminations, Hannah Arendt, ed. Schocken Books. p1 9 Baudrillard, J., 1994. ‘The Precession of Simulacra,’ translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. In Simulacra and Simulation. University of Michigan Press. p8 10 Miller, A. H., 1995. Novels Behind Glass: Commodity, Culture and Victorian Narrative. Cambridge University Press. p52 11 Sekula, A., 1986. The Body and the Archive. Winter, Vol. 39. p26 12 ibid, p11 13 Steyerl, H., 2009. ‘In Defence of the Poor Image,’ e-flux Journal. November. Issue 10 14 Henning, M., 2018. Photography: The Unfettered Image. Routledge. p11 15 Crawford, K., Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press. p94 16 Carroll, L., 1895. Sylvie and Bruno Concluded. Macmillan and Co. Chapter XI 17 Barthes, R., 2000. Camera Lucida, translated by Richard Howard. Vintage. p34 18 ibid, p6 19 ibid, p6 20 Sekula, A., 1986. The Body and the Archive, Winter, Vol. 39. p11

Diane Smyth is Editor of the Photoworks Annual and of the British Journal of Photography, and also teaches photography Theory and History at the London College of Communications. She has written for numerous publications, including The Guardian, FT Weekend Magazine, Aperture, Apollo, The Art Newspaper and Trigger, as well as for monographs and exhibition catalogues.