In this commissioned article for Photoworks Annual, Diane Smyth provides context for the three selected folios and presents the very different, but equally critical, takes on the marketing fantasy of fashion photography.

Alejandro Acin, Claire Lawrie and Karen Knorr’s projects present three very different but equally critical, takes on the marketing fantasy of fashion photography, highlighting the labour behind the glossy facade, the fallout after the trends have moved on, and the gap between the dream and the everyday.

Fashion photography, whether it’s editorial or advertising, shows off clothes currently or soon to be up for sale. It also adds a layer of fantasy that, whether it’s high-octane glamour or anarchic heroin chic, creates a dream-like world that consumers buy into when they shell out on an item. In doing so, it helps create desirable commodities divorced from the less appealing realities of their production, and endowed with values beyond their pure utility. In Marxist terms, perhaps, it helps create commodity fetishes. That’s not the kind of photography that Photoworks Annual has picked out in its Open Call, though all three selected projects are concerned with the fashion industry. In their own ways, Alejandro Acin’s series A Trading Journey, Claire Lawrie’s Mike and Karen Knorr’s Ladies all complicate the usual relationship between fashion photography and the rag trade, by highlighting the labour behind the glossy facade, the fallout after the trends have moved on, and the gap between the dream and the everyday.

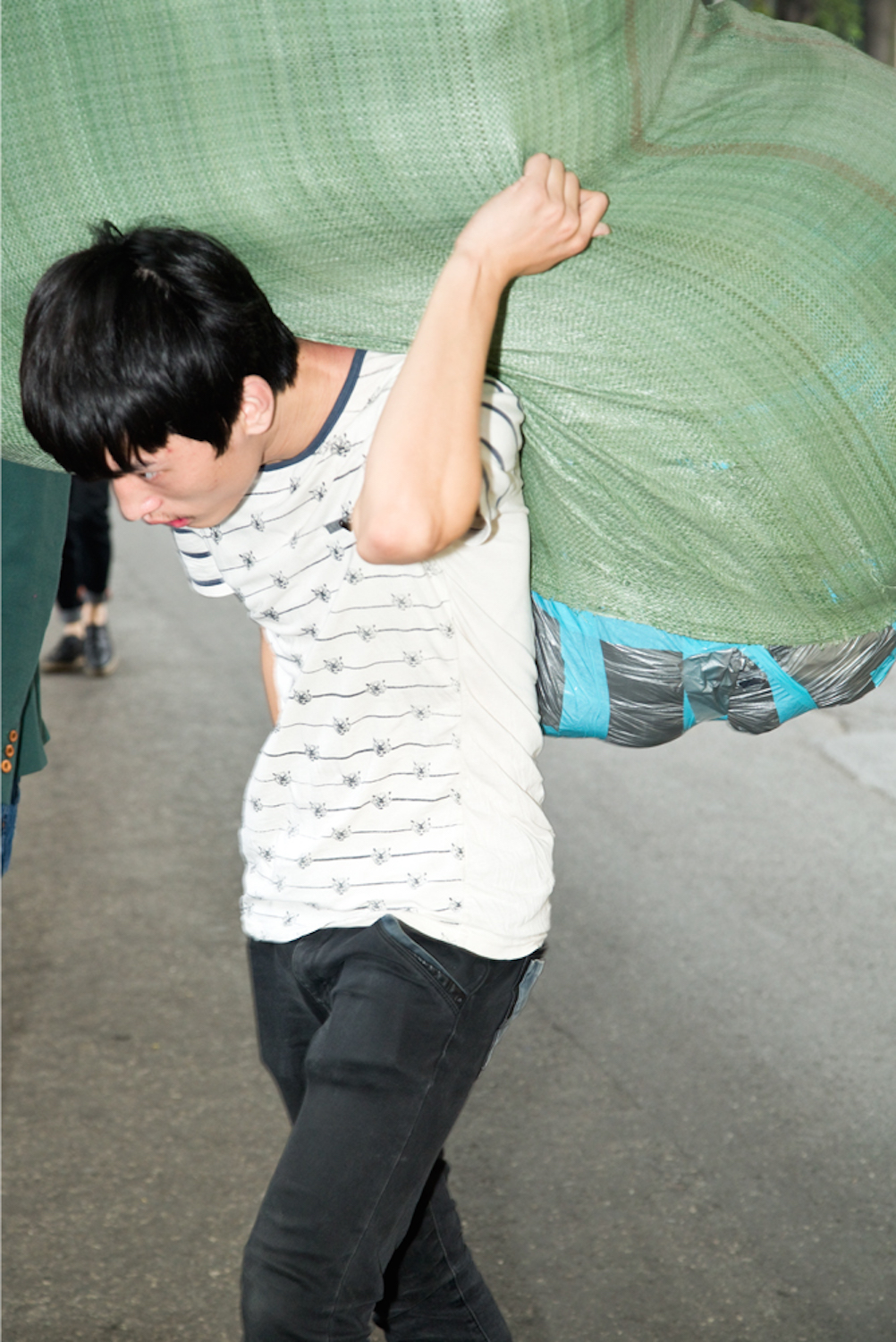

A look behind the scenes in the fashion industry, Alejandro Acin’s A Trading Journey is the most directly subversive—and, perhaps, directly political—of the three. It’s shot in Guangzhou, China’s third largest city and busiest commercial hub, where a quarter of the clothes produced in the country are now made, and where big international fashion brands go to source garments, shoes and accessories before marketing and distributing them around the world. Finding his way into some of the huge wholesale markets in the city, Acin records the overwhelming reality of stalls crammed with goods on sale. ‘Being there is like walking through the backstage of internet trading platforms such as Alibaba, where everything gets packed, wrapped and stored in containers ready to be shipped’, writes the young Spaniard, who is now based in Bristol. ‘Rather than focus on production, with these photographs I want to question the role of photography within the fashion industry by showing the unseen labour and mundanity behind fashion’s supply chain, and the way in which “poor images” circulate within this context. Glamour and prestige are stripped down to show what happens every time an online order is placed.’

To read the rest of the article Become a Member using the link below.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

The ‘poor images’ that Acin references are selfies, used by some of the stallholders to help sell their wares—photographing themselves wearing the items, they pin their shots to their stalls to give buyers a sense of the garments’ potential. In the images he’s submitted to Photoworks Annual, these selfies cannot be seen, however, and the stallholders and porters he’s photographed are also largely obscured, whether they’re hidden behind clothes they’ve hung up as makeshift privacy screens or bent double under their weight as they transport them. Ironically, even in this insight ‘behind fashion’s supply chain’, these people are rendered near invisible, just as the labour involved in producing and bringing goods to market is left out of mainstream fashion photography, and of our understanding of commodities in general. ‘As against this, the commodity-form, and the value-relation of the products of labour within which it appears, have absolutely no connection with the physical nature of the commodity and the material relations arising out of this’, wrote Marx in the first volume of Capital. ‘It is nothing but the definite social relation between men themselves which assumes here, for them, the fantastic form of a relation between things.’

Claire Lawrie’s project Mike also disrupts fashion’s glamorous facade, by focusing in on a former model. Using contemporary shots and archive images, the LCC graduate shows the plight of a man, Michael Schofield, who was once intimately connected with fashion’s fantastical bubble but now deemed too old for mainstream style, whether within the industry or not. ‘Initially I saw in him a symbol of another time, a dapper man, impeccable, who represents through his clothing and hairstyle a connection to memories of men from my early childhood’, writes the photographer. ‘Often, fashion subcultures that compel us in youth are forgotten as we get older, but Mike has carried forward a similar style for as long as he can remember. Fashion is cyclical—but the meanings assigned to our image sometimes no longer translate as the world changes around us. Often, Mike feels as if he is misunderstood; in a society of casual dressers, Mike stands out.’

Mike enjoys the attention his dapper style attracts, Lawrie continues, but at the same time finds it problematic, because ageing and living alone have knocked his confidence. This self-consciousness magnifies his anxiety around his looks and the way others perceive him—paradoxically making the colours of his suits and corresponding ties, handkerchiefs and shoes even more important to him, and making him stand out even further. ‘Mike’s position leaves him conflicted, wanting to be seen and not seen at the same time’, says Lawrie.

Mike’s dilemma demonstrates, perhaps, a peculiar characteristic of capitalism picked out by Walter Benjamin in his ‘Arcades’ project, as interpreted by Susan Buck-Morss in The Dialectics of Seeing—its obsession with the new, with ‘modernity, the time of hell’. This ‘sadistic craving for innovation’, as Buck-Morss has it, can quickly render commodities worthless and even laughable, and seemingly do the same to those invested in them. Identified and identifying with the pieces he wore and the fantasy world he helped create—even himself commodified through his modelling photographs and cards—Mike feels most comfortable when given a way back into the dream, when put back in front of the camera. He first explained his anxieties to Lawrie when she started to film him: by photographing him she can ‘create a space where he can recognise himself again, even if only for the moment’.

Lawrie photographs Mike in sharp, eye-catching outfits against landscapes in which they also act as camouflage—a beige coat against a beige fence, for example, or a pristine white suit against a bright white chalk cliff. Tellingly, in these sessions Mike ‘lets go of some of his inhibitions and regains, through the act of being photographed, a sense of balance, if only for a moment’, the photographer comments. ‘Not only is fashion the modern “measure of time”, it embodies the changed relationship between subject and object that results from the “new” nature of commodity production’, writes Buck-Morss. ‘In fashion, the phantasmagoria of commodities presses closest to the skin.’

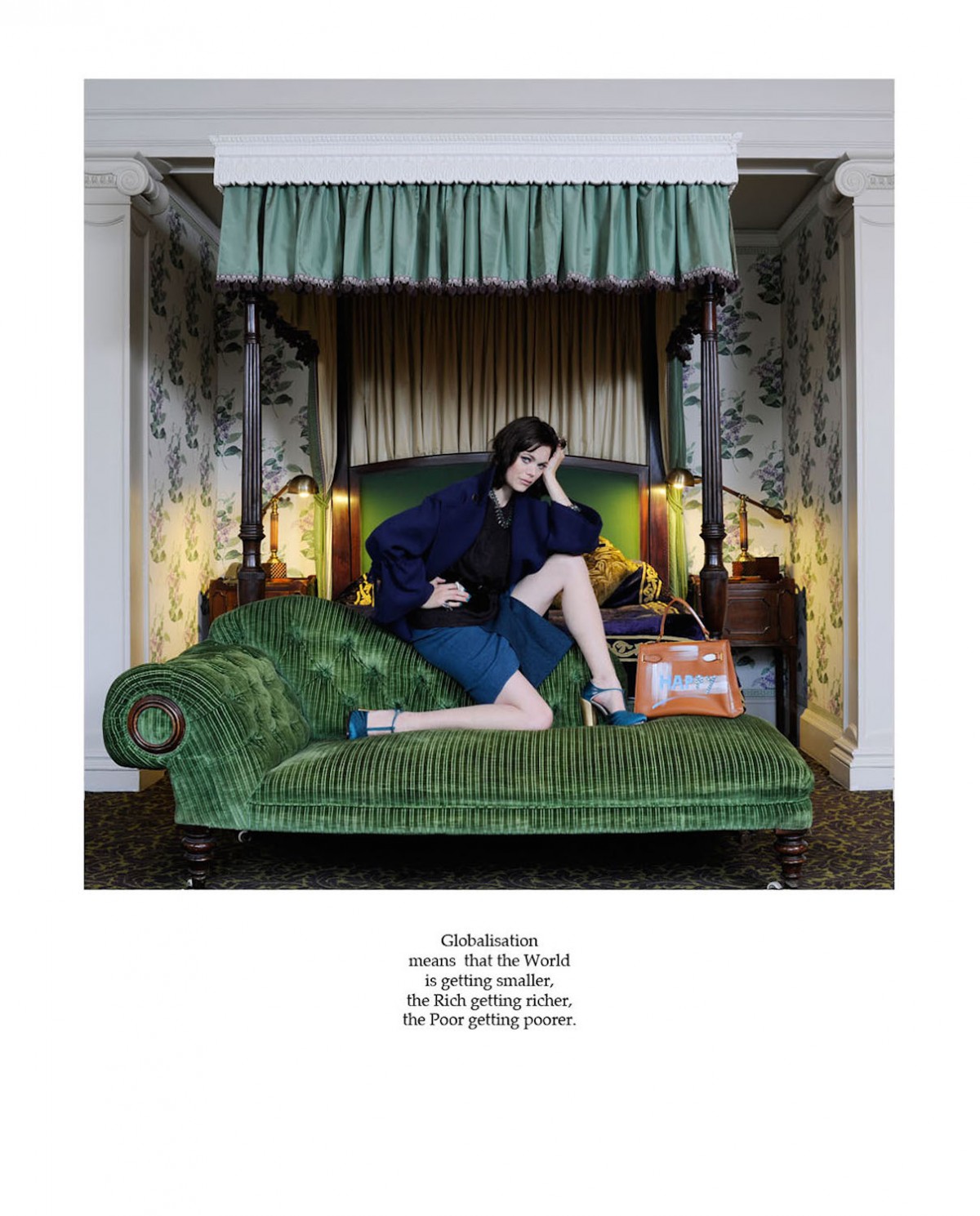

Karen Knorr’s series Ladies also puts the focus on the models, though her images show women as young and beautiful as any conventional model in the exclusive designer pieces and glamorous locations beloved of regular fashion photography. The project was shot in collaboration with a celebrated international stylist, Vanessa Reid, and a story from it published by Pop magazine in its autumn/winter 2011 issue. Even so, both the resulting fashion story and the work published here undercut the opulent fantasy world by pairing the images with deadpan comments from the models.

Some of these texts are darkly funny, bringing the clothes and images down to earth by emphasising the humdrum everyday. ‘What I Fear the most? Moths. They Eat my Cashmere’, says one woman, though she’s pictured in a classic power suit, in a room with idealised, Classical allusions. ‘I always make sure I can see myself in the Mirror, so that I don’t feel like I’m dressed for a part in a Play’, says another, beautiful but sporting an awkwardly stylish trouser suit. ‘I dress for Confidence and Insecurity’, states another, her words and her knock-kneed, hunch-shouldered pose at odds with the machismo of her big-shouldered jacket. There’s a kind of disconnect here between the image projected by the fashion and the photography, and the quotidian experience of life, which helps burst the bubble and bring the clothes back to their utilitarian—or their use—value.

Other comments seem more political, one woman stating that ‘Globalisation means that the World is getting smaller, the Rich getting richer, the poor getting poorer’—though whether she’s in favour or not is harder to gauge. In another image/text pairing, included in the series but not published here, a young woman states that ‘In the Spain of the 1930s there was a Brigade of International Volunteers who went to Fight with the Rebels. No Whisper of that Nowadays’: radical words that sit strangely with the trappings of wealth on show. The image cannot be trusted, it’s implied again, the apparently hermetically sealed dream tainted with wider concerns.

Another comment states simply that ‘China will rule the World’, hinting at another subversion in Knorr’s ambivalent riff on fashion—her use of non-Western sitters, actually wealthy designers and socialites rather than regular models. Knorr suggested using these women early on in the project, she writes, explaining that ‘It was in the midst of the rumblings of the Arab Spring and I was considering hijabs, burqas and shemaghs’; in the end, those particular garments were not included but her choices still suggest ‘the diversity of London’, as she writes, and a shift beyond Western dominance. Perhaps it also suggests the international interests that have always shored up European power—as does the lavish location, the Home House Private Members Club. Home House was originally commissioned by Elizabeth, Countess of Home, who hailed from a colonial family in 18th-century Jamaica; she inherited her wealth from her father and first husband, both of whom were planters and therefore almost certainly slave owners. On the face of it an exemplar of English gentility and propriety, Home House was actually founded on savage international exploitation; similarly, while Elizabeth is buried in Westminster Abbey, a bastion of English respectability, she was known as the Queen of Hell by contemporaries because of her bad behaviour and wild parties. Glittering surfaces, Knorr again implies, are not to be trusted—let alone bought into.

Knorr’s project is also notable because it was originally commissioned by Pop—‘the world’s first superglossy’, founded in 2000 by Katie Grand and Ashley Heath and overseen for three issues by Roman Abramovich’s partner Dasha Zhukova. How subversive can a story be if it depicts fashion and is commissioned and published by a magazine intimately bound up with that industry? Very, supporters might argue, pointing out that Pop presents an eccentric take on fashion that has also attracted artists such as Allen Jones, Cindy Sherman and Broomberg & Chanarin, and that its title suggests Pop Art and therefore the idea that art that engages with popular culture can also comment intelligently on it. Critics might cite Marxist literary theorist Frederic Jameson, though, and his contention that capitalism absorbs even the most radically intended gestures. ‘Not only punctual and local counter-culture forms of cultural resistance and guerrilla warfare but also even overtly political interventions like those of The Clash are all somehow secretly disarmed and reabsorbed by a system of which they themselves might well be considered a part, since they can achieve no distance from it’, he wrote in Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.

Either way, the images that Knorr has published here are not the ones that appeared in Pop – the images in the fashion magazine were in black-and-white, not colour, and therefore arguably at one further remove, and in addition, portraits such as that of the woman dressing for ‘Confidence and Insecurity’ show her looking considerably more doubtful here. More fundamentally, in presenting her work in this new context, outside the fashion industry, Knorr is able shift the emphasis away from the clothes and towards its more radical potential. Fashion photography can include ironic and even critical images but, in approaching this genre, Photoworks is free from the business of shifting product—or at least from the business of shifting fashion.

[/ms-protect-content]

For other articles, click here.

For more about the Photoworks Annual Issue 23, click here.