Contradiction, a certain tentativeness, the rolling out of threadbare clichés and an apologist tone, all characterise the largely uncritical art-world appraisals of Nobuyoshi Araki to date.

The exhibition at London’s Barbican Art Gallery (2005) and a mammoth 720-page book, Self, Life, Death, published by Phaidon provide yet another opportunity to assess his work.

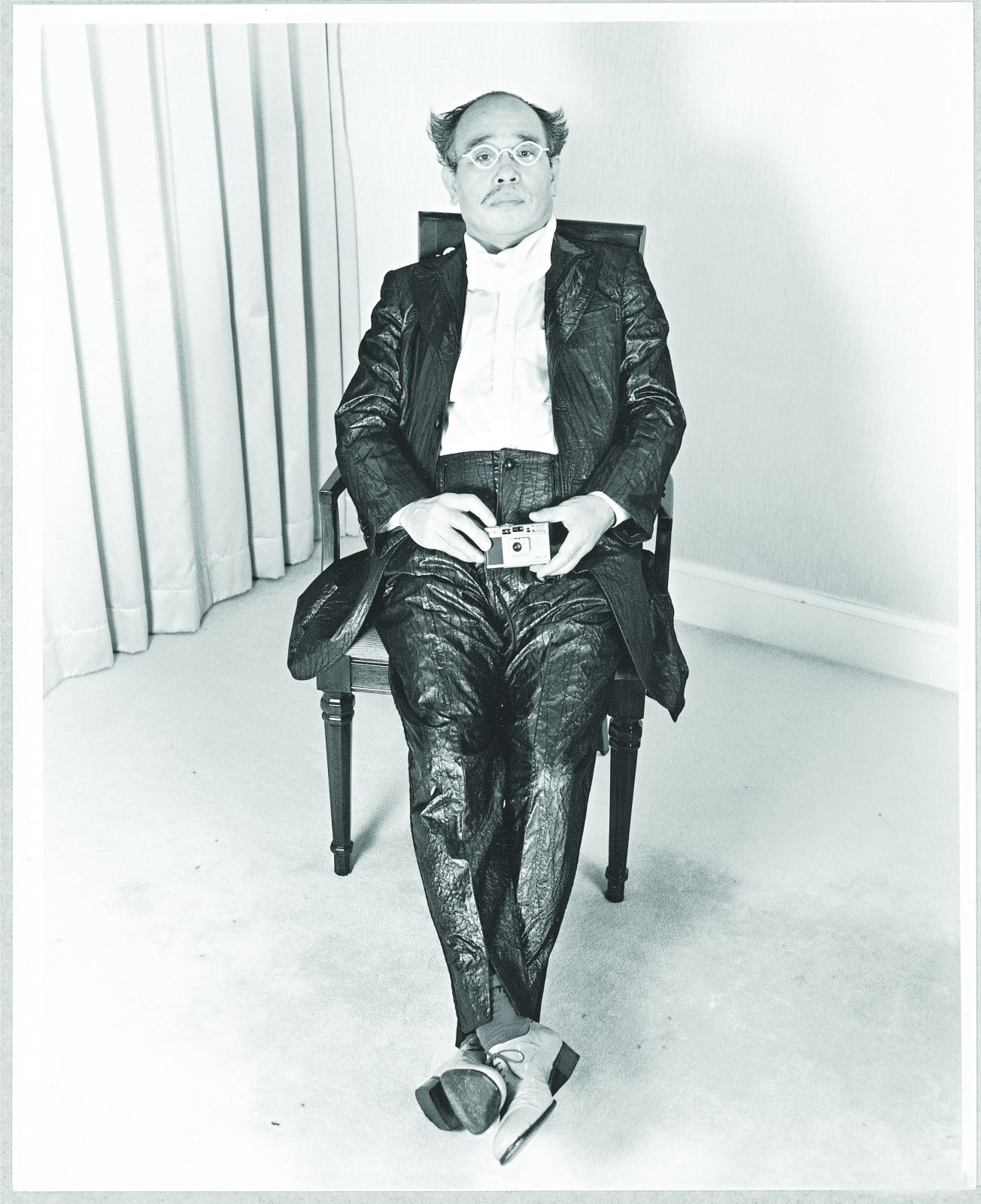

In some ways the many slight and uncertain responses to Araki are not surprising since the sheer volume of his photography from 1970 to the present is daunting enough, while his scattergun approach to subject matter and to grouping pictures seems – like the work of so many other new realists – to be pitted against any reasoned interpretation. But also, to approach this prolific Japanese photographer with any degree of seriousness is to risk sinking into the quicksand of a post-modern theatre of the absurd, into a sex pantomime of superficiality, excess and outrage – fuelled by the juice of media celebrity – that surrounds Araki and his work. And as we slowly go under, overwhelmed by the incessant stream of images and disturbed by his portrayal of women, we risk looking like a po-faced moralist from a bygone era, unfashionable and unable to read the complex cultural and sexual codes that he apparently plays with. For Araki’s stance is unfettered and unabashed; like some ageing photo-punk, revelling in his post-pc offensiveness, lasciviously indulging his own obsessions and fantasies without ever pausing to reflect, he is forever moving on, sucking at his country through his camera. He is, it is said, the quintessential post-modern artist, a post-history operator whose photographs most accurately mirror the often bizarre and kaleidoscopic face of contemporary Japan.

Trying to pin down what really endears Araki to his supporters has always been something of a no-brainer. He has been variously lauded for his artlessness, his sentimentality, his honesty; he’s a realist and a fantasist, he’s prolific, he is photography as an adrenalin rush, he breathes images; we see the world unmediated through his camera; he doesn’t think too much, he doesn’t do philosophy; he’s kitsch, he’s has this profound insight, he’s a self-proclaimed genius; he’s a crusader against censorship, he’s a liberating figure in a repressed Japanese culture hung up on tradition and etiquette; he allows women to give free rein to their sexuality; he’s a joker, a clown, he doesn’t take himself too seriously and anyway he’s a great artist…

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

All this must be a convenient smokescreen for Araki the man of action, lack of coherence is a welcome means of deferring serious commentary, it allows him the space to work, to carry out his mission without pause or unnecessary distraction. It suits him to play the happy fool, as Jonathan Watkins says in the new Phaidon book: ‘His insistence on happiness is like Warhol’s bland utterances, a foil for a profundity that lies at the heart of his work. His position is philosophical, in a Nietzschean sense, suspicious of conventional morality, preferring an apprehension of ‘present experience’ to introspection, and essentially realistic.’1 But the deferment and the play with his persona is taken even further. Araki often suggests that he loses himself in the act of photographing, that he disappears into or merges with the camera, and that consciousness, too, is lost to the mechanics of recording: ‘I turn myself into a copier. Photos are nothing but copies of reality, that’s the only truth.’ ‘…I’m oblivious of the camera when I’m shooting because I feel like I’m actually inside it. Or perhaps I feel there’s a camera inside me or that I’m a camera myself.’

For a free-wheeling post-modernist this has an old-time modernist ring to it, reinstating the myth, as Christian Kravagna has pointed out, of the ‘hyperactive obsessive, driven by a mission to transform the world into images’, an artist machine who does not conceive or consider but “who is propelled by an inner necessity”. He achieves authenticity precisely because he doesn’t think but ‘breathes photography’; as this camera body he has a floating but charged existence above and apart from ‘socially conditioned patterns of perception.’2 But we must be wary here of submitting to the myth and the mask. Throughout Araki’s work there is careful consideration, both in the making and editing of his pictures, in his extravagant exhibition presentations and especially in his three hundred or so books. After all the photographic ‘work’ doesn’t ever simply appear at the point of exposure or in the darkroom, it is the product of a process full of planning and judgement; however hyper the activity is, thinking is always implicit in the work itself.

Patently, Araki’s most controversial images, and those that quite obviously don’t fit into the manic point and shoot story, are highly considered. They are the often elaborately staged, sometimes tableaux-like photographs of women either trussed with rope, erotically posed, decorated or penetrated with various objects or otherwise intimately scrutinised by Araki’s camera – to the point of exaggeration. The photographer’s presence here is always felt, the photographer’s directorial role, his gaze, his prompting; the implied exchange of looks, however coaxed (or maybe automatic), is there to underline that these are collaborative events, with the photographer a physical participant in the game, the photographic and the sexual act more or less intertwined. It seems part of the Araki code that within these ‘collaborations’ he can and will celebrate his predatory role, celebrate the phallic lens, and that neither should he contain his excitement. But, putting Araki’s personal satisfaction aside, it is often argued that his creation of this highly sexualised visual space in Japanese culture is a liberating force; that he presents a challenge to a culture that has repressed women and denied them their sexual indentity for centuries. The ropes, it is said, drawing motifs from Japanese porn, become ‘ironised’ in Araki’s pictures, or perhaps just re-presented as straightforward symbols of this repression. So the fact that Araki’s women are the passive objects of his desire, and through him those of men generally, is given a double rejoinder: (a) yes, but these women are complicit in the picture’s performance, they want to be sexualised in this way, they want to take part and in particular they want Araki to photograph them; and (b) there is a very positive and radical outcome in this for Japanese culture, namely that in Araki’s photographs women are at last expressing themselves, openly and defiantly declaring their sexual identities, their own desires.

There are levels of social and historical complexity in this which cannot be adequately drawn out here but even on the surface the justifications seem to me irrelevant to the debate about what these images come to mean when they are circulated, or what impact they might have on general attitudes to women, since the images almost immediately transcend their original, culturally specific context. Like all images they become free agents, whose reading and meaning is determined by where and how they are seen. And these photographs, more than most, travel internationally through many different contexts, from art and fashion to pornography. Perhaps we should consider Victor Burgin’s remarks from 1982 on the authorship of photographs, which, while in many ways contested now, would still seem to be relevant here: ‘Neither the photographer, nor the medium, nor the subject is basically responsible for the meaning of a photograph. The meaning is produced, in the act of looking at the image, by a way of talking…It is the given field of discourse that is the real ‘author’, producing both photograph and photographer as well as, in the act of looking, the viewer.’3

In the great wide world of images it is the erotic in Araki that is continually seized upon; it is the photographs of naked, trussed and eroticised women that have been seen again and again and have created the photographer’s fame, it is the whiff of controversy, of the illicit, that has drawn the crowds. Araki’s fame and celebrity in Japan is extraordinary, unparalleled by any other photographer anywhere in the world. In Tokyo he is high-fived in the street by men and mobbed by young women clamouring to be photographed by him (a Japanese game show even offered that privilege as a prize); he receives letters from women telling him how far they are prepared to go, what they are prepared to do in his pictures, out-grossing each other in what appears to be a frenzy of exhibitionism. A recent Channel 4 documentary, Fake Love, concluded that this frenzy had more to do with the particular nature and intensity of celebrity culture in Japan, and that over and above any desire to ‘collaborate’ in or be liberated by Araki’s photographs the desperate need to be photographed by him is simply a hysterical craving for fame by association. It is something that gives all those exchanges of looks, all that collaborative intimacy, a different edge, might it be Araki the agent of fame, rather than Araki the photographer or the man that is being smiled at?

Embracing celebrity, buoyed up by the culture that has created him, Araki now appears happy to play Araki to the hilt, firing off crass sexual inuendos as if to a bad adolescent script. But the leering, overheated man behind the lens barely conceals another sadder one, the one who continually equates sex and death and who is the source of all the melancholy and even morbidity that flows from his work. There is even a sense of melancholy in his endless production, the sense that photography for him is an addiction and that that is really his ultimate subject, as Ian Jeffrey has said in essay in the new Phaidon book: ‘(Araki) is to be understood above all as a creative temperament living in post-history, inspired by the hope that he can bring things to a conclusion or somehow achieve creative closure. He can’t, of course, because he has set himself too large a task with his aim of comprehensive coverage. In that case what we witness is the creative effort itself, carried out with whatever materials come readily to hand.’4

In confronting any serious addiction there are always moments of shocking lucidity, and Araki’s work is punctuated by many of those moments, when, for example, gentleness and eloquence arrive, when the image storm is calmed. Even at his most raucous and confrontational, Araki is prone to snatch a gorgeous sad beauty from commonplace things and situations. But the addict is ultimately a bore; too immersed in himself, too tiring to be with, too reliant on the delusions and compliance of others around them. Most great art comes from a singular and obsessive attention to things, it is borne of an urgent desire. Yet great art opens out from that point. Spending time with Araki’s work is, for me, like being confined in his addiction, like being dragged on an interminable journey of the self with photography as a desperate act of constant renewal and with photographs as gaudy and pale replacements for life.

[/ms-protect-content]

Published in Photoworks Issue 5, 2005

Commissioned by Photoworks