Vilem Flusser, an exemplary twentieth-century philosopher of photography, wrote that a photographer is not a “Homo Faber” but a “Homo Ludens,” and a trickster.

In his words, the photographer’s freedom lies in “playing against the camera”. This might be “the only form of revolution left to us”.

“Communication error!” screams the disgruntled voice of my used and abused computer. For me, not only the act of photographing but also of making individual prints has to be a mini-performance of intervention and imperfection. I interrupt my printer, all its prerecorded lamentations notwithstanding, and pull the photographs prematurely, leaving the lines of passages and blotches of transgressive colours. This “human error” makes each print unrepeatable and uniquely imperfect. A disruptive touch defies the understanding of photography as an art of mechanical or digital reproduction. The process is not Luddite but ludic, not destructive but experimental. Each work is a fragment. An error has an aura.

My project, Nostalgic Technologies, mobilises the tension between those two words. While I might have grown up in the dark ages of the Cold War, known now as “the culture of analogue,” I am not homesick for the off-red colours of the GDR Kodak film of 1970s and 80s. If there is a longing for anything, it is not for the analogic mode of picture-taking but for the critique of the technological apparatus that accompanied it. In our age of digital techno-utopianism a playful and occasionally revolutionary technique of reflective judgment is often treated as if it were an obsolete technological function.

Techne, after all, once referred to arts, crafts and techniques. Both art and technology were imagined as the forms of human prosthesis, the missing limbs, imaginary or physical extensions of the human space. Avant-garde artists and critics used the word ‘technique’ to mean an estranging device of art that lay bare the medium and made us see the world anew. If artistic technique revealed the mechanisms of conscience, the technological special effect domesticates the illusions and manipulations. Artistic techniques follow zigzag movements between dreams and hopes of the improbable future, and of the unexplored potentials of the past. Perhaps we don’t have to throw out the baby of critical play together with the basket of analogue technology. We can smuggle it into the digital culture with a magic touch and a sly of the hand.

During my art practice of “playing with the camera” and occasionally with my printer as well, I came up with the conception of the off-modern as a third-way of thinking about technology, technique, trace and error. It focuses on the anxieties, as well as the unforeseen potentials of the present, rather than the clear oppositions between analogical and digital technologies. Instead of fast-changing prepositions—“post”, “anti”, “neo”, “trans”, and “sub”—that suggest an implacable movement forward, against or beyond, in my art practice I propose to go off: “Off” as in “off quilter”, “off Broadway”, “off the path”, or “way off”, “off-brand”, “off the wall” and occasionally ‘off-colour’. Off-modern is a detour into the unexplored potentials of the modern project. It proposes to brush history against the grain, to quote Walter Benjamin, and venture into the side-alleys of technology, while at the same time engaging with chance encounters in our decaying material world.

My global photographic errands go together with technological errors that capture a manual labor of memory and a “personal” touch that imprints on the images like a disruptive signature. Modern architecture in partial ruins coming mostly from the boundaries of Europe—East and West reveals uneven modernities and histories out of synch. While working in the former war zones in the former Yugoslavia, I didn’t want to be another “disaster tourist” (as the locals call the traumaphilic foreign visitors). Instead of focusing on the spectacle of destruction, I reflected on the art of everyday survival. A once-shelled building in Sarajevo with wounds and scratches on its façade has been inhabited again and now the satellite dishes spread out of its ruined balconies like desert flowers.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

I capture the act of looking back at the snapshot from Sarajevo, taken right after the war, re-photographing it against all instructions, keeping in the glare and the passing shadows, occasionally dropping a piece of trash or a flower on the old picture, leaving in all the blemishes that a professional photographer would try to remove. The cities in transit include abandoned or foreclosed homes and scaffolds with the dream homes of the future. Among them is a construction site in Manhattan, behind St John’s cathedral, the home of an immigrant peacock, and the windows of the real estate office in Cambridge Mass., with pictures of sold and foreclosed homes during the financial crisis of 2008-9. The photographs house the transits and offer “portable homes” that we can carry with us when we travel light. They might not commemorate the present and the sense of being there, the way Roland Barthes once mythologised it, but hopefully they capture our zeitgeist in all its uncanniness.

Why focus on breaks, errors and syncopated camera movements? A perpetual unease and mis-adjustment is a part of my immigrant existence, of my multiple, hypehnated identities. Writer and photographer, Russian and American. Another Russian-American writer, Vladimir Nabokov, compared the experience of immigration to the syncopal kick that off-centers one’s life and art, and yet makes life worth living. Speaking of his own forced exile, he wrote: ‘The break in my own destiny affords me in retrospect a syncopal kick that I would not have missed for worlds.’ The syncopal tale of immigration is about loss and displacement, not reconciliation. Syncopation is about the impossibility of transcendence and fusion. The syncopal tale is based on sensuous details, not symbols; it is the opposite of synthesis. Syncopation does not restore the lost home; it is present as a trace, an estranging disharmony, a foreign accent. Or, even more than an accent, the syncopation affects the syntax of the immigrant performer that resists complete assimilation into the non-immigrant metaphors of universal longing. At best, when and if an immigrant becomes an artist, she manages to transform the loss into a musical composition, a ciphering of pain into art.

A syncopated art is at the core of the new immigrant arts where existential anxiety of networking offers an uncanny parallel to our current technological anxieties. The modern immigrant, who speaks with an accent in both foreign and native languages, does not merely mourn her losses, but plays a trickster in the world of transits, passages and infinite connectivities, developing alternative solidarities. A heightened sense of the virtuality of existence and estrangement does not allow one to drown in the smooth slickness of the digital screens.

I use the digital camera out of simple convenience but I continue playing against it like I did with my other cameras. I still go out into the world like Dziga Vertov once did hoping to “catch life unaware” and then make an associative montage of the “kinofacturas” even if I doubt that it would bring forth a radical transformation of the world. And yet we have to do what it takes to exercise the modicum of freedom—defined by Hannah Arendt as a “miracle of infinite improbability”—that occurs regularly in the public world. In order to do so, we have to play against the camera.

Blackberries and Black Mirrors: Haunted Modernities

The black mirror was an object of cross-cultural fascination, trade, conquest and sometimes misappropriation. The Aztecs used black mirrors made of obsidian or volcanic glass in divination and healing practices. If a child was suffering from “soul loss,” for example, the healer would look at the reflection of the child’s image in a mirror and examine his shadows. After the discovery of the “new world,” Europeans appropriated the obsidian for anatomic theaters and occult practices, dissecting dead bodies and bringing ghosts back to life. Since the Renaissance, European painters and architects— including Leonardo da Vinci and Claude Lorraine—have used their own black mirrors to focus on composition and perspective in the landscape and to take a respite from colour. Sometimes the artists stared into the black mirror to take a break—to catch a breath, so to say—in order to purify the gaze from the excess of worldly information. The black mirror allowed them to suspend and renew vision.

In the nineteenth-century, black mirrors were rescued from oblivion and found their place in the new popular culture of the picturesque. English travelers carried miniature black-mirror-like opera glasses, framing and fetishising fragments of landscape. Absorbed by the possibility of capturing the beauties of the world in the palm of a hand, voyeurs of the picturesque left the world behind. The American doctor and spiritualist Pascal Beverly Randolph went beyond the picturesque. Believing in the mystical vitality of the black mirror, he supposedly used opium and the ‘sexual fluids’ of his wife (and mistress) to polish its surface. At the turn of the twentieth century, modern artists from Manet to Matisse resorted to the black mirror, not to reflect an image but to reflect upon sensation itself, on the ups and downs of euphoria and melancholia, or the syncopations of modern creativity.

Although the black mirror dims colours, it also sharpens perspective. It does not frame realistic illusions, but instead estranges perception itself. The black mirror offers a different kind of mimesis and an uncanny and anti-narcissistic form of self-reflection, in which we spy on our own phantoms in the dim internal film noir.

We no longer live at the end of history, or at the time of the forward march of technology and endless growth. Ours is an off-modern moment, a moment of clashing modernities, industrial and digital. We have become accustomed to accelerated rhythms of time and the urgent demands of instant, but not intimate, communication. Surrounded by garrulous screens, we barely get a quiet moment of contemplation. The dim realm of personal chiaroscuro has given way to the pixelated brightness of a homepage, bombarded by hits and unembarrassed by total exposure. This new form of overexposed visuality has not been properly documented. When captured on camera, it appears ambivalent, confusing and barely readable.

What if we use our digital devices improperly and transform their pixelated interfaces into reflective surfaces? Suddenly our touch doesn’t open a new virtual screen but reframes our prosthetic devices altogether, revealing alternative connections and flows between our uneven modernities and immigrant solidarities. The familiar digital screen seen from an oblique angle becomes an uncanny black mirror that connects the past and future.

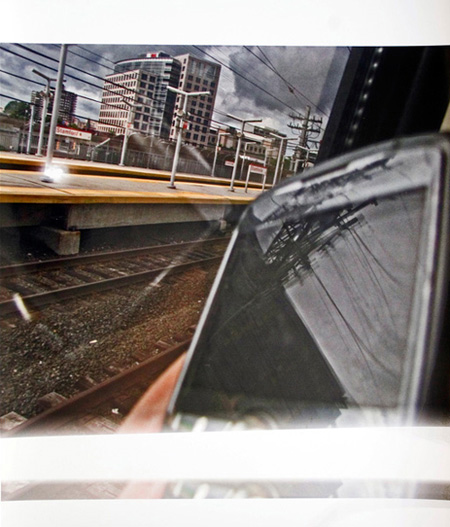

When a digital surface becomes a black mirror it reflects upon the clashing forms of modern and pre-modern experience that coexist in contemporary culture. Black mirrors engage with pictorial and photographic genres of the past to document a confrontation of modern industrial ruins and virtual utopias. I took a train journey through the American industrial landscape, multitasking with clouds on my digital screens. I used the digital surface as a black mirror to nature and the contemporary anxieties on the ground and in the air. The surface of my broken powerbook looked like a milky-way spotted with forgotten stars.

I want to catch the digital gadgets unawares, confront them with each other and the alchemistry of cross-purpose. I put different forms of modern and pre-modern experience, of technological, existential and artistic in counterpoint. This project is techno-erratic and not techno-erotic. It is engaged in errand and detour, deviating from the march of progress or the upward diagram of the new gadgets sales.

Multitasking with Clouds: Immigrant Blow Up

The nineteenth-century was the age of panoramas. Daguerre began as a panorama artist and invented photography only after a fire had destroyed his panorama house. Art and technology competed in the public imagination of the new space of modernity. Photography was the next step in the game of illusions. Soon afterward, the train journey became a part of “panoramania” and framed many real-life panoramas. It was never merely about arriving at a destination but also about window-travel. Many works of nineteenth-century literature are framed by the train journey. Its unhurried rhythm inspired strangers to unburden themselves, to think about the meaning of life. We remember how one famous passenger confessed to his accidental neighbour that he might have killed his wife over a Beethoven sonata. And another unfortunate heroine found her end under the wheels of a train, as if punished by the writer himself.

Panoramas became victims of their own success and in a peculiar reversal of fortune, from a painting of a landscape, they began to refer to the landscape itself. When we speak of a panorama today, we mean nature (often at its most scenic), rather than the now-obsolete art. Panoramas occupied the space of play between nature and art. Besides the dream of the grand illusion and all-encompassing perspective, they also revealed a horizon of finitude, the limit of human vision. The painter of panoramas strived to create a life-like illusion, always aware of its impossibility. Painting en plein air was like trying to square a circle and dwelling on its elusive curves.

From painted panoramas to photographic exposures, from real to fictional train journeys, the road led to the discovery of cinema, which was imagined in a novella by Villiers de L’Isle-Adam, The Future Eve, some fifteen years prior to the technological invention. Cinema would borrow the language of panorama (“panning” and “panoramic shots”). Movie houses shared architectural features with old panorama houses and with train stations.

The early twentieth century became the age of cinema, which continued its own train travel from the first film by the Lumieres, The Arrival of the Train, to Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera. The latter film’s hero challenged “bourgeois realism” and jumped on the train tracks (this time not to kill himself but to expand human vision with an under-the-wheels panorama). In a more conventional fashion, many a romance was happily consummated with a train driving into a tunnel and the cheerful words “The End” written over it. Much of the early cinema was non-narrative. The proto-documentary, The Arrival of the Train, featured non-centered frames with actions taking place chaotically and spontaneously in different parts of the image. This kind of cinema was about narrativity itself and its euphoric potentialities. It allowed the spectator a narrative freedom to play with unpredictable adventures and roads not taken. It did not depend on the formulaic plots that would dominate cinema with the introduction of the Hollywood code in the 1930s nor on the carefully calculated interactivity of the new gadgetology.

The industrial landscape was contemporary to cinema’s golden years. Factories would give jobs to immigrants, and rails would transport them. Rails, not roots, were what mattered. Rails should not turn into roots. Otherwise they bind you to the soil and never let you go. Cinema celebrated industrial construction but also revolutionary destruction, often simultaneously. Thus in the films of Sergei Eisenstein, especially in October, the old monuments would become ruins only to be transformed into new monuments that used some of the same reconstruction and retouching as the old ones.

Later twentieth-century visual art stopped trusting the enlarged renaissance perspective of the panoramas, turning to a more self-reflective and ironic conceptual perspective. It explored virtuality in its original sense, as imagined by Henri Bergson, not Bill Gates. It was the virtuality of human consciousness and creative imagination that evades technological predictability. Yet much of conceptual art was still haunted by the horizon of finitude, a certain clouded existential panorama (whether it acknowledged it explicitly or evaded the question is another matter).

In the early twenty-first century, the Netscape took over the landscape. Just as the word “mail” turned into the retronym “snail mail”, the word “window” will soon become “snail train window”. Microsoft Windows offers faster and more exciting panoramas than the “snail train windows” of the malfunctioning and underfunded Amtrak service.

My neighbour on the train needs neither snail window watching nor snail talking with a stranger. She is happily interfacing in private. In a world of endless pop-up windows, horizons and limitations will be abolished. All you need is better technology and death itself will become a thing of the past. To paraphrase Faulkner, the past will never be dead again. It won’t even be the past.

Furtively I look out at the landscape of industrial decay, ruins of former factory towns, framed by endless pipes and wires.

From a certain uncomfortable angle, the digital screen turns into an old-fashioned reflective surface, shamelessly invaded by passing clouds and sunset panoramas. The computer is only a material thing, after all, however light it is. I am perched on the edge of my seat trying to commemorate the flickering shadows on my neighbour’s computer screen without disturbing her cinematic pleasures. I feel like a private detective spying on transience itself. At some point in the DVD movie a murder happens and the dying man screams for help in the middle of the clouds and trees.

Is there a corpse there or just another ill-shaped cloud? Multiburst does not allow for blow-ups and zooms. It resembles the “primitive cinema” of the early twentieth-century. I cannot rewind it either, for the clouds and shadows would never conspire in the same way.

As I capture the low-tech corpse on my neighbour’s reflective digital screen I recognise with anxiety that my playing with the camera does not result in chancy innovation but in appropriation. Why am I aiming at this vanishing corpse with such desperation? By chance my erratic photowork turns into a digital hommage to Antonioni’s Blow Up. My version is not slick but well-intentioned. The existential puzzle is still there and the resolution is low, just like in the good old days.

Blow Up, inspired by Julio Cortazar’s short story ‘Las Babas del Diablo’ offers an existential zoom on the paradoxes of the real and the pitfalls on the analogue that no contemporary special effect was able to match. I watched the Antonioni films in Leningrad and their auratic cinematic alienation had a profound effect on my life, even on my decision to immigrate from the former Soviet Union. At the age of eighteen my understanding of the political was a mixture of rebellion against the coercion and claustrophobia of Soviet life at the time that destroyed what remained of ideals of justice and the foreign existential dream of liberations. I could blame Antonioni for seducing me with the auratic cinematic alienation. As a teenager I loved the freedom that I saw in his films, the freedom of long takes, of individual anxiety and critical reflection, wander and wonder, a luxury of alienation. It was explained to us as a “Marxist critique of the bourgeois society” but it seemed to be also a form of individual creativity, a way of playing against the apparatus. There was breeze in the heroine’s hair and a long duration of non-obligatory time that we can only dream about.

The twilight time is short, the DVD movie is almost over, along with the time of panorama watching.

My Chicken Sierra Special purchased in the café car is getting cold. The “Sierra” part of it, a sun-dried tomato smashed into the Wonder Bread, has an aftertaste of another time. “Dad, is the moon moving?” asks a little boy behind me.

“No, it’s very far away,” the father explains.

“It’s us who are moving…”

I smile and turn around.

“What’s your name?” I ask the boy.

“I forgot,” he answers.

The windows are dark now, turning into imperfect mirrors in which the passengers can see themselves framed by dangling ticket stubs. Some are still multitasking, others just staring into space.

I defined nostalgia as a longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed. Nostalgia appears to be a longing for a place but actually it is a yearning for a different time—the time of our childhood, the slower rhythms of our dreams. The nostalgic feels stifled within the conventional confines of time and space. In a broader sense, nostalgia is rebellion against the modern idea of time, the time of history and progress. The nostalgic desires to obliterate history and turn it into private or collective mythology, to revisit time like space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition. Hence the “past of nostalgia”, to paraphrase Faulkner again, is not “even the past”. It could merely be better time, or slower time. Time out of time, not encumbered by networking and appointment books. Nostalgia, in my view, is not always retrospective; it can be prospective as well. The fantasies of the past determined by the needs of the present have a direct impact on the realities of the future. The consideration of the future makes us take responsibility for our nostalgic tales. Sometimes it is not directed toward the past either, but sideways. And this sidelong glance might prove to be the most revealing.

The photographer has to photograph what inspired her anxiety as if performing a strange ritual of artistic homeopathy. If we manage “to photograph all conceptual oppositions”, to quote Jacques Derrida, we can reveal the haunting of our contemporary technology, the apparitions behind the apparatus. The erring off-modern photographer might be one of the last critical content providers, multitasking with clouds and affectionately engaging ruins and construction sites in our disharmonious material world. This might be what Benjamin once called a modern love, “a love at the last sight”, emotion in transit.

[/ms-protect-content]

Buy Photoworks issue 18