Nikolai Ishchuk’s Offset series pulls apart the family album. Ishchuk has digitally reworked a set of found snapshots, separating the central figures from each other and leaving the middle of the frame oddly vacant.

This gesture is a direct function of the Photoshop offset filter referenced in the title, a tool that automatically splits an image down the middle and reverses the pieces so that the centre moves to the edges and the edges meet in a sharp central seam. Ishchuk has smoothed these seams without correcting the perspective. Thus in some of the images there is a sense of space bulging and buckling between the divided members of the family. The images are not intended to deceive. In several cases the appearance of a disembodied shoulder or hand on the opposite side of the picture provides a trace of the operation that has taken place. The titles of the images reflect the number of pixels separating the figures, and emphasize that these open manipulations are designed to reveal rather than conceal.

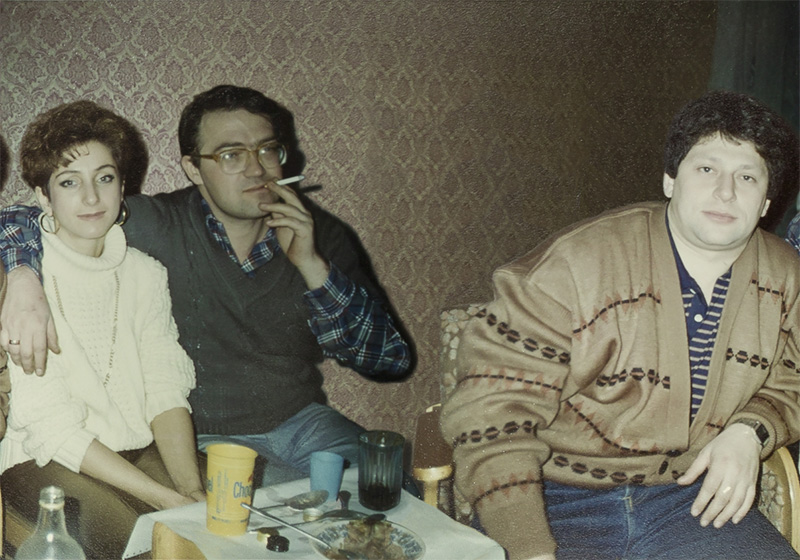

Although the photographs have been altered, it is still possible to piece together a conventional family narrative, rich with idiosyncratic detail. A petite redheaded woman and an affable-looking mop-headed man grow into a young family with two sons and age into a handsome older couple. Their increasing affluence is illustrated through changing accessories and backdrops, cheap sweaters and dreary wallpaper giving way over time to sportswear, fancy party clothes, middle-class holiday destinations and expensive function rooms.

The reconstructed walls, curtains, pillars, trees, etc. that take centre stage are not entirely plausible; with their slightly warped perspective, they produce an unsettling void in the middle of the frame. Ishchuk makes these negative spaces even more palpable by presenting the reworked images alongside a set of glossy black and white collages, silhouettes that reproduce the negative spaces he has created in another subset of images. The awkward abstract shapes are like Rorschach blots, springboards to projection. To link the works back to the materiality of the family album, Ishchuk has kept the series snapshot scale, with the re-worked images held in place with clear photo corners.

Banal yet endlessly fascinating, family photographs invite us to identify, project and judge: “My mother had that same hairstyle in the late 1980s!” “I wonder if the mother prefers the older son?” “Didn’t the husband’s weight yo-yo, while the wife stayed so slim…” Ishchuk’s interventions point us beyond the anecdotal particulars of an individual family’s photographs to the mechanics of the genre. His striking new compositions invite us to analyse the ways we perform our closeness for the camera and construct our happiness in relation to a series of pre-determined photo opportunities.

Encouraging us to examine the images more closely, Ishchuk’s manipulations raise flickers of doubt about the authenticity of the source images. Is that really the same dad in the later scenes? Are the more formal party images actually staged? A number of artists including Eva Stenram, Zoe Crosher and Walid Raad work with found (or allegedly found) photographs in related ways. A common thread running through their very different projects is an unreliable author/narrator whose interventions may not always be entirely logical. Stenram has short-circuited the mechanics of soft core and hard-core pornography, as well as NASA images of Mars, creating pictures with a peculiar presence of their own. Crosher rephotographs and re-frames the eccentric archive of an individual/persona called Michelle duBois, exploring the construction of feminine identity through photography. Raad has worked under the pseudonym of The Atlas Group, using still and moving images to interrogate the documentation of conflict. Each of these series has uncanny aspects, pointing to ways that photographs can simultaneously confirm and undermine our understanding of the world. The first generation of writing about digital imaging was rife with anxiety that digital manipulation would undermine the truthfulness of the photographic image. Contemporary photographic artists including Ishchuk have embraced digital means to tease out what is repressed and forgotten, not necessarily into a clear message, but into a thoughtful, pleasurable awareness of the ambiguities occluded by traditional photographic genres.

Published 19 November 2013

Commissioned by Photoworks