The rapid introduction of digital technologies has not only been revolutionary, but also unsettling on a personal and wider societal level.

Born at the start of the 1980s, I am old enough to remember a time before we all had mobile phones and personal computers, yet young enough to have used both for almost half my life. If I use Marc Prensky’s terminology, I probably sit somewhere between a ‘digital immigrant’ and a ‘digital native’. I would not regard myself as an early adopter of new technology, but I have generally embraced many of the changes they have introduced into my daily life and working practice.

Nevertheless, I still cling on to vestiges of the analogue world through my love of large format film and my refusal to ditch printed books, magazines and newspapers. When I bought my first mobile phone in 1998, I recall voices of concern about their safety. I don’t remember any government declaration that they were safe to use 24/7, yet most people’s initial anxieties appeared to dissipate over time. We seemed to collectively file away our worries under ‘keep using until told otherwise’, and grew to adopt and depend on wireless technology.

When I first started researching the controversial condition known as Electromagnetic Hypersensitivity (EHS) my initial reaction was skeptical, but this quickly turned to confusion when I realised that I had stumbled upon a very divisive area of science. EHS sufferers claim that man-made electromagnetic fields from mobile phones, wi-fi and many other common devices make them ill. They report a multitude of symptoms such as headaches, rashes, memory impairment, heart palpitations, sleep disorders, fatigue and nausea. Many public health experts and psychologists claim EHS is psychosomatic, yet a significant number of scientists also argue that it is possible for electromagnetic fields to have a biological effect on humans. Doctors, academics, sufferers and support groups promote differing nomenclatures, diagnostic criteria, aetiologic hypotheses and treatments, resulting in entrenched divisions.

Anyone with an allergy will know how limiting and difficult it can make one’s life. Yet as frustrating as hay fever or as dangerous a nut allergy can be, sufferers can generally go about their daily life without feeling ill. EHS sufferers on the other hand claim they are made sick by something invisible, something that travels through the air and is pervasive in some form in all but the most remote parts of the world.

A search on Google will bring up a plethora of websites dedicated to spreading information about the dangers of mobiles, wi-fi, smart meters, baby monitors and many other devices. There are accusations of cover-ups, links to cancer, industry sponsored research and government oversight and/or complicity. I have read a vast amount of material on the effects of electromagnetic fields on our health. Some of it has made me contemplate a device-free life in the countryside. Yet other papers have assured me that I have nothing to fear. Highly qualified and distinguished academics and scientists from either side of the debate are presenting contradictory arguments and the internet has become a battleground for information supremacy. Although the web provides an incredible platform for information exchange, debate and peer support, it also has the power to spread misinformation and reinforce confirmation bias. When research is released stating that EHS is either real or psychosomatic, a range of counter studies are put forward. Discerning fact from opinion becomes increasingly difficult, and even the official messages are confusing. The Council of Europe, the European Environment Agency, and other reputable bodies are calling for governments to use the precautionary principle – given the mistakes we have made in the past with tobacco and asbestos – and are urging that the scientific basis for the present standards on exposure are reconsidered to take into account biological effects on human health. Yet Public Health England concludes that the research so far suggests that the technology is safe, and psychologists argue that multiple studies into EHS have failed to provide any hard evidence that it is anything more than psychological. They assert that most EHS sufferers have other underlying health conditions or a misplaced distrust or fear of these technologies, and that their symptoms are a result of the nocebo effect.

Despite this conflict of opinion, both sides are generally agreed that whatever the cause, the symptoms are real and that people with EHS suffer significant social and personal challenges, frequently impairing their ability to function normally in society.

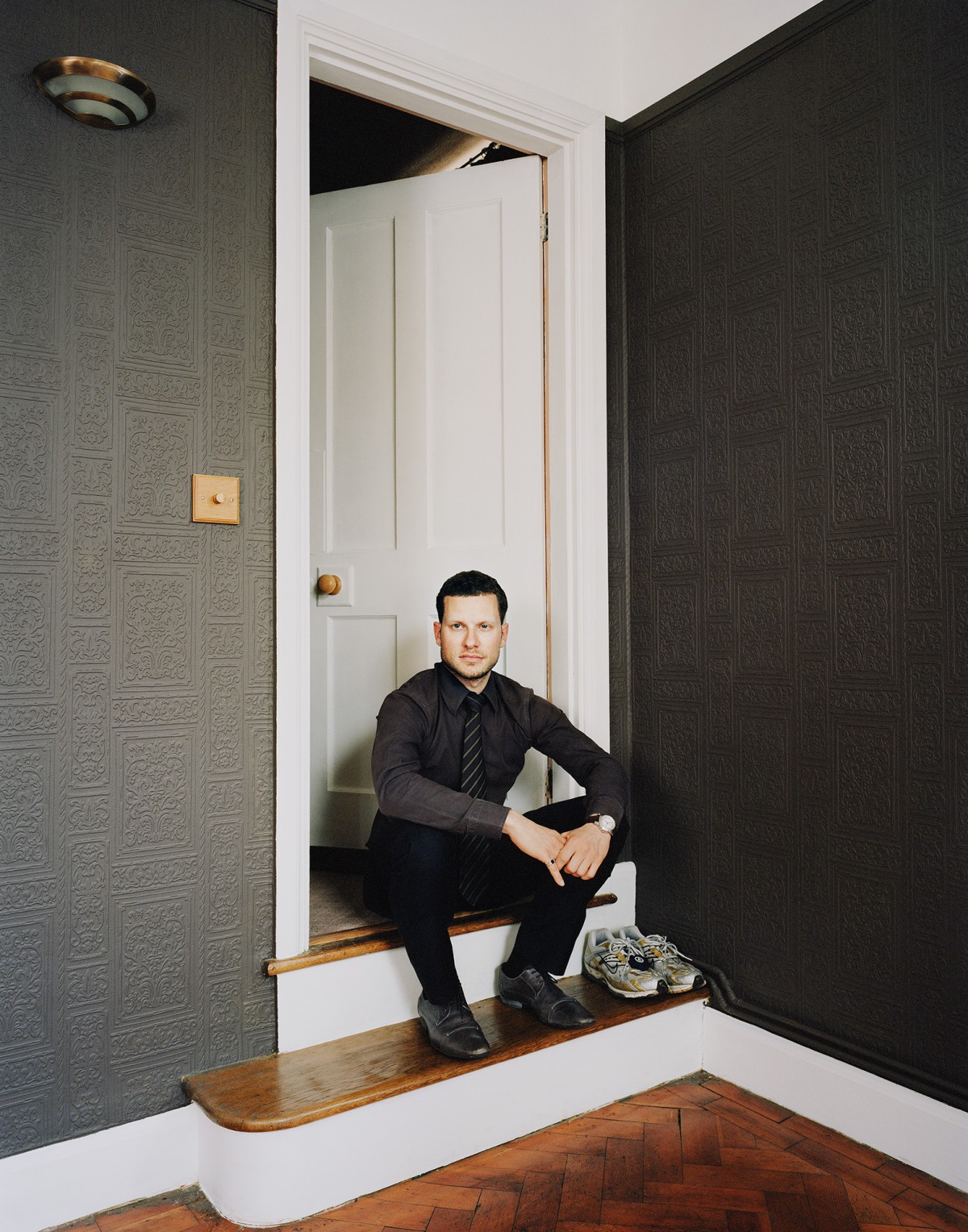

When I began work on Electrosensitive in early 2012, I grappled with how to represent sufferers through photography alone and realised that a series of still images would not be enough. I wanted sound and video interviews to document and explain their stories in greater detail and richness, and thanks to advances in digital technology I have been able to do this more easily than ever before. After contacting dozens of sufferers and experts, I travelled around the UK over the course of a year to photograph and interview them. In March 2013, my work from this first stage was published in the Guardian Weekend Magazine. The misleading headline ‘Electrosensitivity: is technology killing us?’ sparked a vociferous reaction underneath the online article. The spectrum of responses ranged from immediate dismissal to sympathy and agreement. Detractors attacked electrosensitives, labeling them as technophobes that use pseudoscience to fight their cause. Impassioned comments from both sides illustrated how divisive electrosensitivity is and that we’re still far from finding a consensus. Everyone has an opinion on this issue, some are well informed, some are not.

My intention has not been to judge or authenticate the arguments from either side. However, I felt compelled to share the experiences, stories and voices of sufferers who feel misunderstood and ignored, and to highlight the apparent inconsistencies within the scientific research. Those I have interviewed showed courage in speaking openly about their condition. Despite facing ridicule and dismissal, they passionately believe that wider public awareness is vital. Although their concerns and arguments run counter to prevailing opinion and perception, this does not mean they deserve to be silenced. We should continue to innovate, develop and embrace new digital technologies that make positive contributions to our lives. However, in the case of wireless technology at least, recent history would suggest it unwise to let convenience and dependency stifle an on-going and serious public debate about any possible effects on our health.

–

Published 16 September 2013

Commissioned by Photoworks