Ale Cukar of RUIDO Photo describes the story of Humberto Roco, the protagonist of Toni Arnau's project Paraná River.

That night – the night in which Humberto Roco saw the ghost canoe- the moon was shining: there was no need for a torch or a lantern.

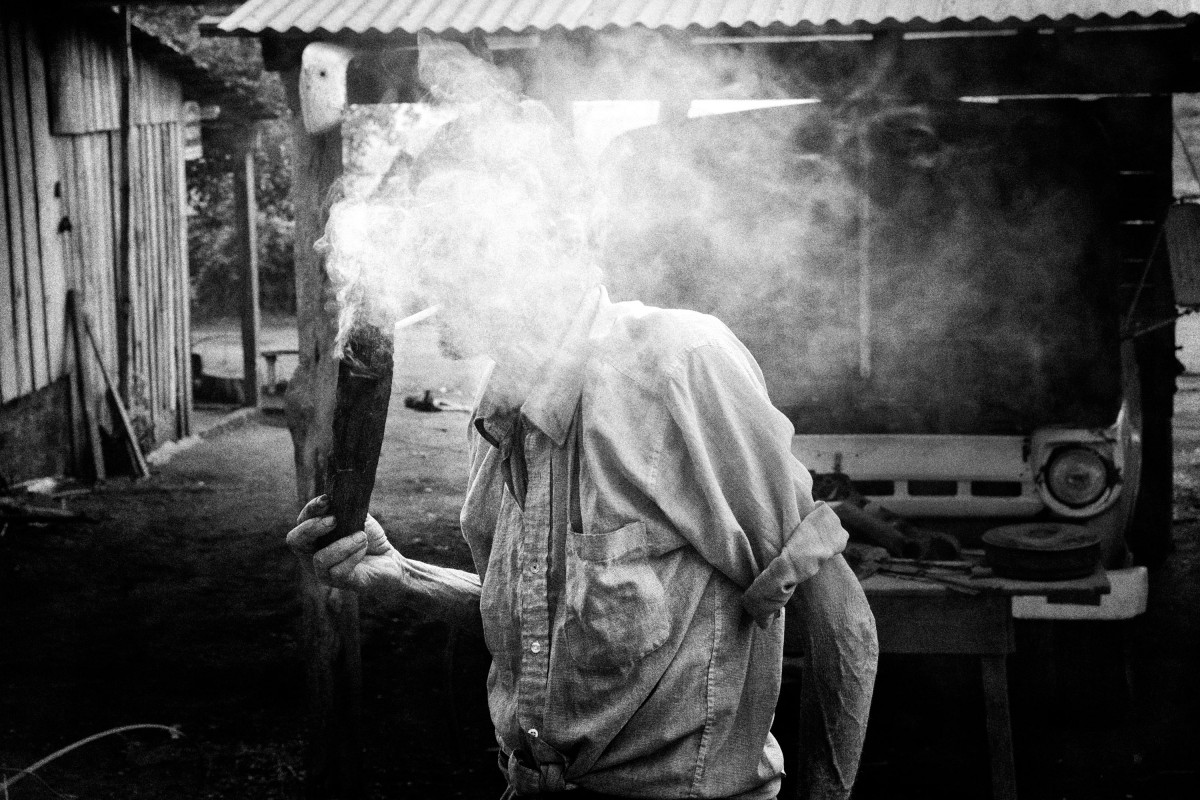

It was autumn, and it was late, but he went out fishing anyway. He wrapped up, prepared the net, climbed onto the boat and started rowing. He reached the middle of the water on the River Paraná, he tried his luck…nothing. He threw the net again once, twice, ten times, still nothing. He sat down in the empty boat, almost adrift, lit a cigarette and then he saw it: the apparition.

-There were two people in the canoe; the one rowing was half hiding his face, the other one greeted me.

Humberto did not see and did not hear it arrive: there was no light, no noise, no splash of the oars. It was sudden, like a ghost.

-One asked me how the fishing was going, and I answered “not good”. He said: “Don’t worry, it will get better. Your troubles will get sorted out”.

-And did they get sorted out Humberto?

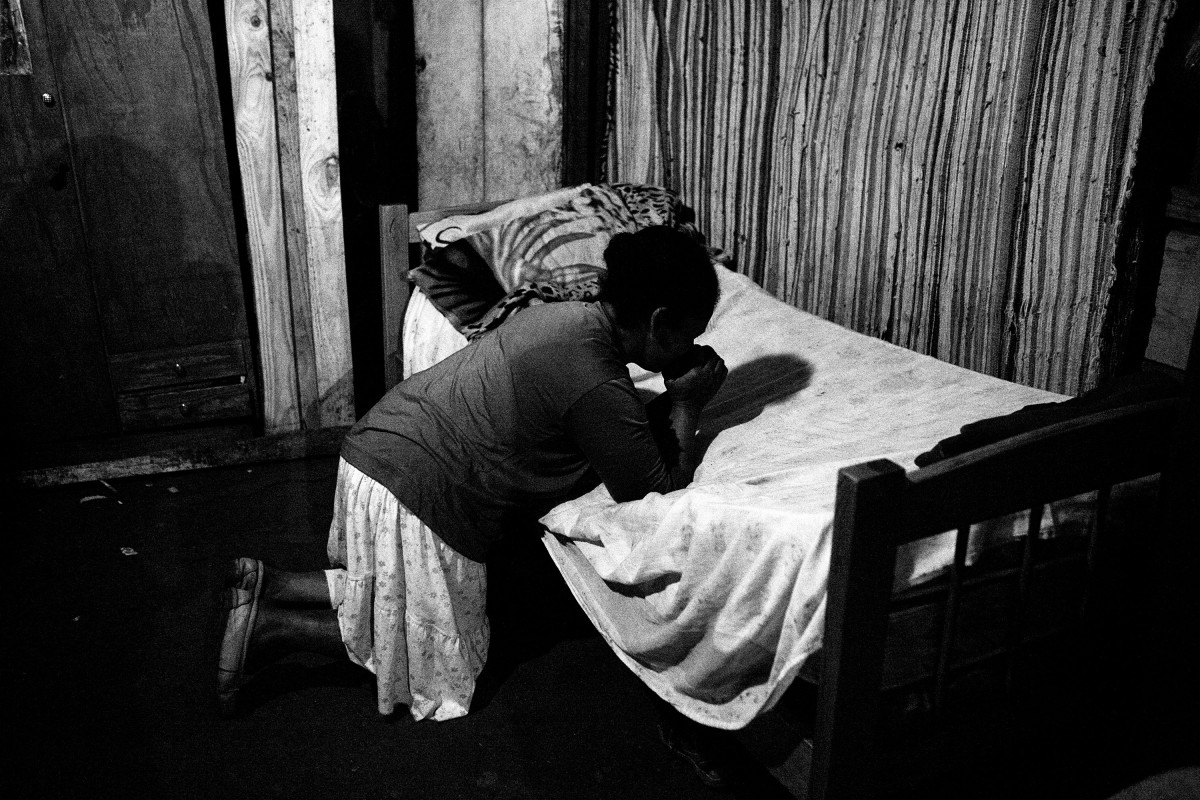

-No, but I have faith.

Humberto Roco was already devastated. His wife had left, his house belonged to someone else, and three of his thirteen children had died – two in his arms. And the fishing, which he had been doing half his life, was poor.

That was two years ago. Humberto is still living in a hut, without a wife, and without nets. The boat vanished, gone forever. He still has faith. He still believes in the words of those two ghosts.

-Let’s go to the kiosk, I’m going to buy my breakfast, that is, cigarettes.

Humberto returns with his packet of Imparciales, lights the first one and goes into the hut to heat the water for the mate*. He drinks Aguantadora**, which is a bad plant, but of course he is resistant. Humberto is 64 years old, and no one would say he looks younger. His clothes are old and too big for him. His hair – grey and white – is a thick mane, his eyes clear and watery, his teeth are too few.

The older Roco siblings arrived in Los Arenales – this fishing neighbourhood in the outskirts of the city of Paraná- more than three decades ago. It was July 1976 when Humberto had lost his job as a watchman in Río Cuarto (Córdoba) that he and his second wife began looking for a place to live, work and bring up their four-month-old son. Brazil was the original idea; he did a stopover in Paraná. He started fishing because he had a vague idea about how to do it and he needed the money. They never continued the journey further.

Humberto supported his family by fishing. He went on to have eleven children with his second wife- the one he arrived with- but he hardly sees them anymore, she went back to Río Cuarto and took all the children with her. He had two more children with his third wife, but she left with another man and now does not let him see the kids, even though they live in the neighbourhood. Humberto’s first wife, the love of his life, died of an overdose in Córdoba when they were barely more than teenagers. Now he is in love again, with Andrea, a young girl of twenty something. Humberto is one of those who will die and come back to life for love. On his left arm he has a faded tattoo of a feminine silhouette with no head, feet or hands. On his mobile, he has Andrea’s photo. His passion for women is infinite yet his luck is almost as bad as the fishing.

Lately, Humberto hardly goes out to throw the net. The river that fed his family does not give what it used to. The uneasiness can be seen in the canoes arriving to the shore of the neighbourhood: big fish no longer hang over the gunwale; there are no happy faces. A couple of months ago Humberto’s net, fishing line and his bicycle were stolen, that’s why he uses the canoe more like a means of transport than anything else. And he seldom goes fishing because –in truth- his body cannot take it any longer.

-See? I walk straight like a vine’s trunk.

His back broke in two in a fall from a staircase and ever since he walks with a stick, trying to support a bent body at a right angle. His inguinal hernia only pulls him further downwards. But when he climbs onto the canoe and he starts rowing (because his boat doesn’t even have a motor), his body adapts, his muscles take shape, he becomes younger: he still has the strength to go crosscurrent and throw the mesh full of weights, to see if something takes the bait to throw it onto the grill.

The canoe, “Chiche Franco”, is moored at a tongue of the river that the fishermen use as a parking place for the boats. Humberto’s hut is right on that shore, almost touching the water, as it goes out and come in every time there is high tide. He does not live in the house he managed to build with materials years ago. His hut, on one of the many unpaved streets are named after fish (Patí corner with Surubí, or Boga, or Armado, or Moncholo), is only a couple of blocks away from his old house. That is where his ex-wife, his two younger children, and the man who took everything that was his, reside.

The hut is in the place where the fishermen meet to work, where the street ends and the river starts. Next to the hut, on the shore of the Paraná, ten or fifteen men get together every day. They share a “cancha”, a stretch of river of 100 by 500 metres which they all cleared together: they pulled out the sunken trunks and the pieces of iron stuck to the bottom to be able to throw the nets without having them hooked and broken.

Today is dark and cold. It is not later than 6 in the evening and they are arriving. The first ones light the fire and settle on some chairs that won’t withstand any more recycling. The dogs bark at everything. Work starts, again. The cancha system has a slow pace, and is therefore, exhausting. One canoe goes out at the time, so there is always waiting. Every now and then, someone gets up, places the boat facing the water, checks the net –of about 60 or 70 metres long by 2.40 wide-, cleans it and then fits the weights, neatly, so when he is letting it down over the gunwale it does not tangle. They are going to be repeating the same thing for many hours. They have been repeating the same thing for all their lives.

-Are you not preparing anything for dinner?

-No, bread and mate. If we cook, we don’t go out.

The truth is, if they cook, they drink wine, and you know what happens in the river with the wine.

–

Translator’s notes:

* Mate is a traditional South American caffeine-rich infused drink. It is prepared by steeping dried leaves of yerba mate in hot water.

** Aguantadora is the branded name of the yerba mate he drinks, and it also means resistant. In addition, “bad plant” may also refer to weeds which are also very resistant plants.

–

Text by Ale Cukar

Translation by Aleceia de Juan

–

RUIDO Photo are exhibiting their work as part of Brighton Photo Biennial’s Five Contemporary Photography Collectives exhibition from 4 October – 2 November at Circus Street Market, Brighton.