I met the Brazilian artist Patricia Azevedo in 1994 in Sao Paulo, Brazil, at a photo festival portfolio review session.

She had queued up, along with many others, to show me and Brett Rogers her work, which immediately stood apart from the overwhelming prevalence of beautifully composed and artfully printed reportage photographs.

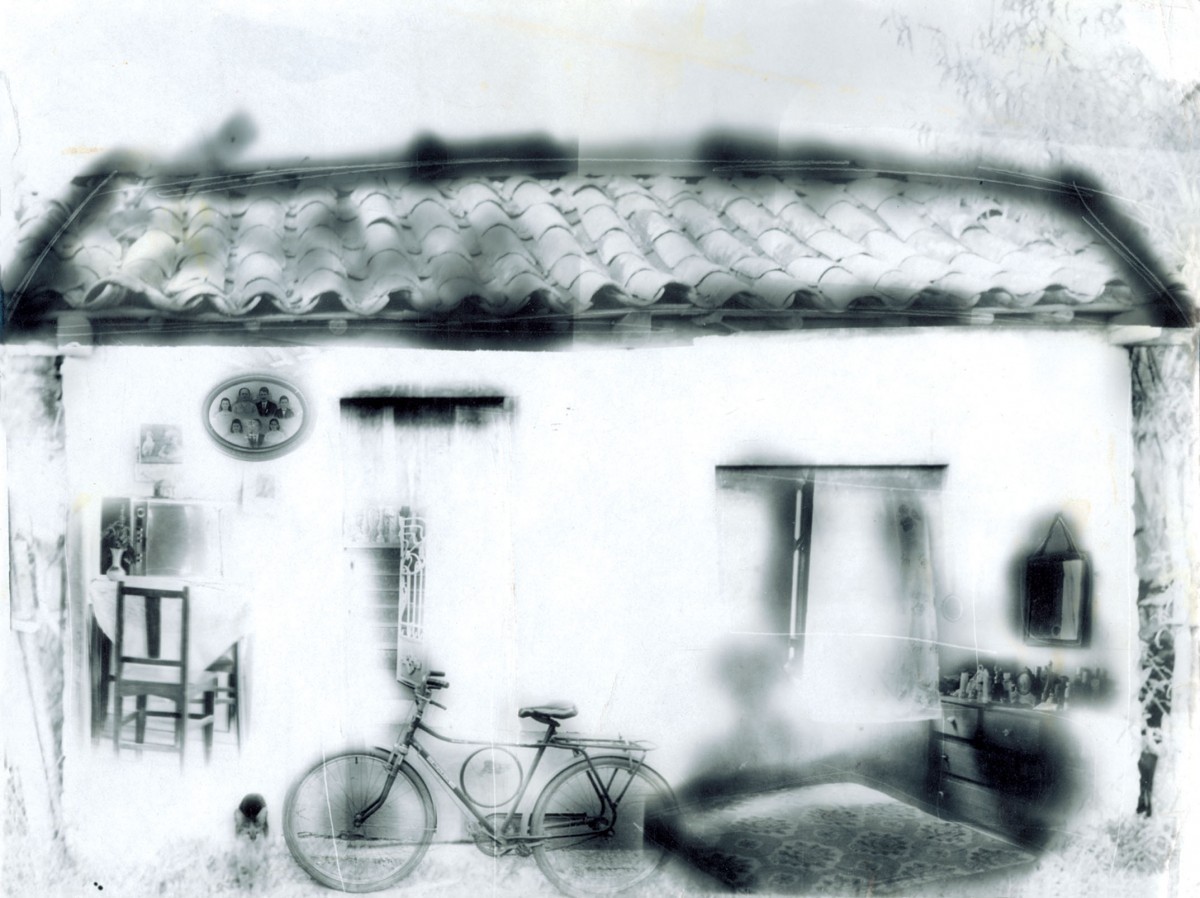

First, she presented Memory Series, Workers Houses, intriguing photo composite pieces, imagined and ghostly images of vernacular Brazilian housing, the product of a painstaking and almost unbelievable working method, more akin to Oscar Gustave Rejlander’s combination prints of the 1850s than anything else I could think of. And yet, Azevedo leaves so much more to chance than Reijlander or more recently Vik Muniz or David Mach who glue multiple images together to create spectacular collages.

Azevedo’s artistic process is distinct, indeed unique as far as I know. It is not collage. She works in the darkroom, projecting sections, often from many different negatives (archival imagery as well as her own), making multiple exposures onto a single sheet of photographic paper. The production of one 10 x 8 print may take hours, carefully loading and unloading negatives, adjusting the enlarger head to scale, exposing and masking particular areas of both negative and photopaper. It is only when the paper is immersed in the developer that she can finally examine the image she has composed.

Alterations can only be made by starting the whole process again, from the beginning. She fine-tunes exposure times and composition, perhaps looks for additional or different images to include. She often makes a rough pencil or scratch ‘drawing’ sketch onto the photopaper under the red safelight gloom, to aid positioning. And so she goes on, to try again, and again, working on the same picture, numerous versions (every one of them unique) until she is satisfied.

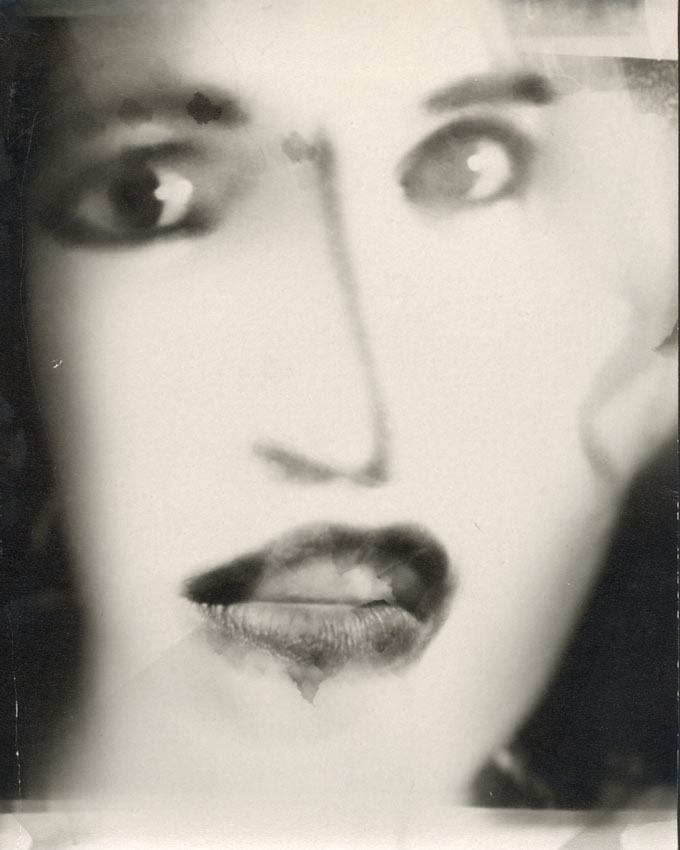

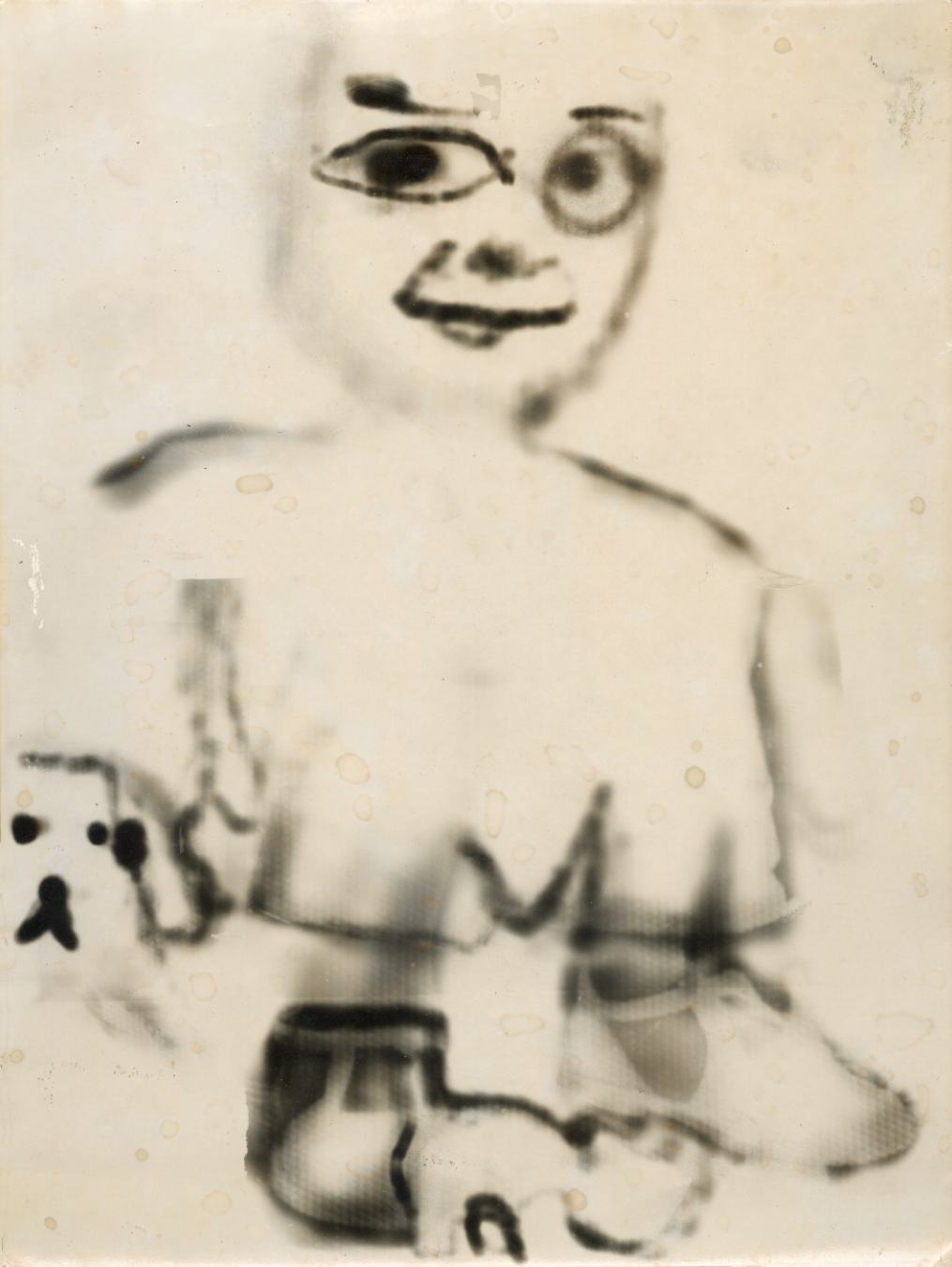

Other series employed a similar working method. There were strange, disjointed portraits and what she called ‘Dream’ pictures or Images from the Spirit. From the outset, I was hooked. The prints were never pristine, bearing scratches and marks as well as creases and even finger smudges, from being moved in and out of lightproof bags so many times in a tiny and sweltering darkroom / cupboard.

She described her work to me as research about the internal as well as the external, the buildings and rooms and household and personal items, the body and mind, about somehow ‘giving expression to people’. And I loved the entire process of photographic deconstruction and reconstruction, of mixing up different buildings and interiors to create new, imaginary places, which nevertheless had a loose foothold in the real world. A messy, handmade, naiive technique, a bit like drawing with an unreliable ink pen, in the dark. Expressionistic works about memory and imagination entirely dependent on memory and imagination, also intuition, luck and determination. A process doomed to fail but generating beautiful photographic art.

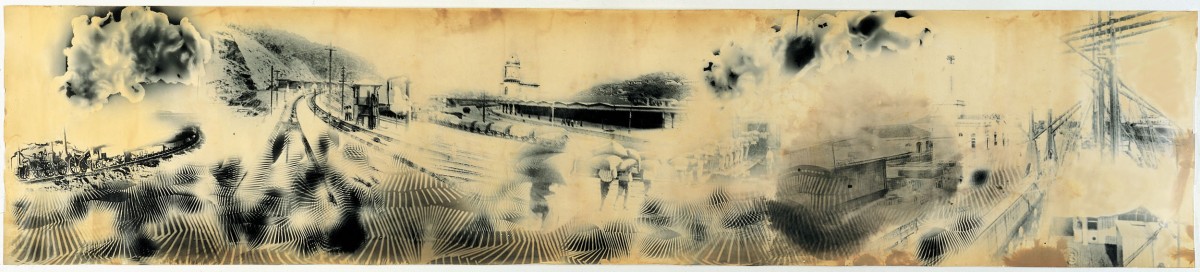

She went on to produce larger scale panoramic works, including Oblivion Series, City Stories (1997), which involved hundreds of exposures from over 50 negatives, also utilizing photogram techniques and ‘drawing’ with an ultra-fine torch light, on a 3m x 50cm roll of paper. An epic work reflecting on the modern history of Brazil, featuring trains, railways, landscapes, the docks and the slaves (Brazil didn’t abolish slavery until 1888) carrying sacks of coffee or sugar aboard cargo ships bound for North America and Europe. In Oblivion No’s I – IV she sandwiched half fixed and barely washed fibre based prints – still wet – between two sheets of glass and left them outside for months. Parts of the image faded, there is chemical discolouring and staining, bleach crystals formed from the residues of fixative as well as rot and mould.

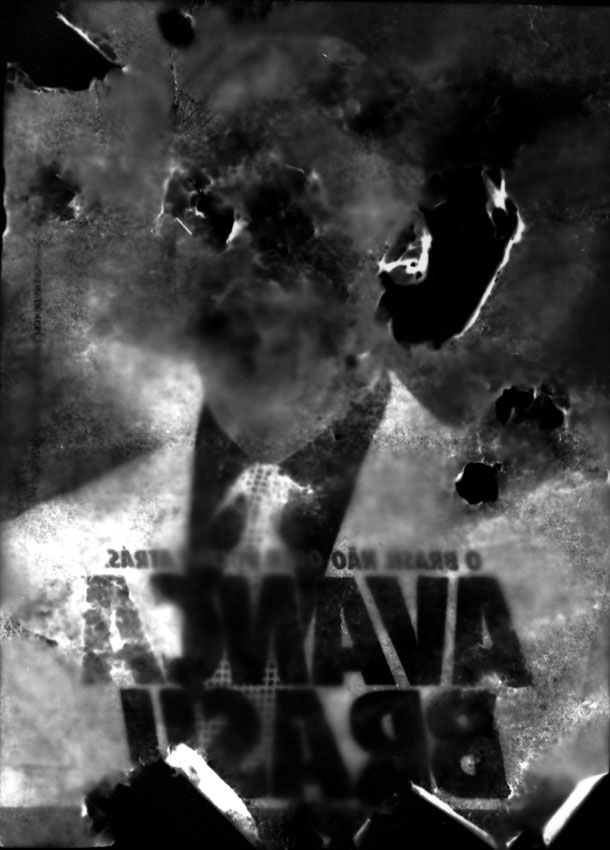

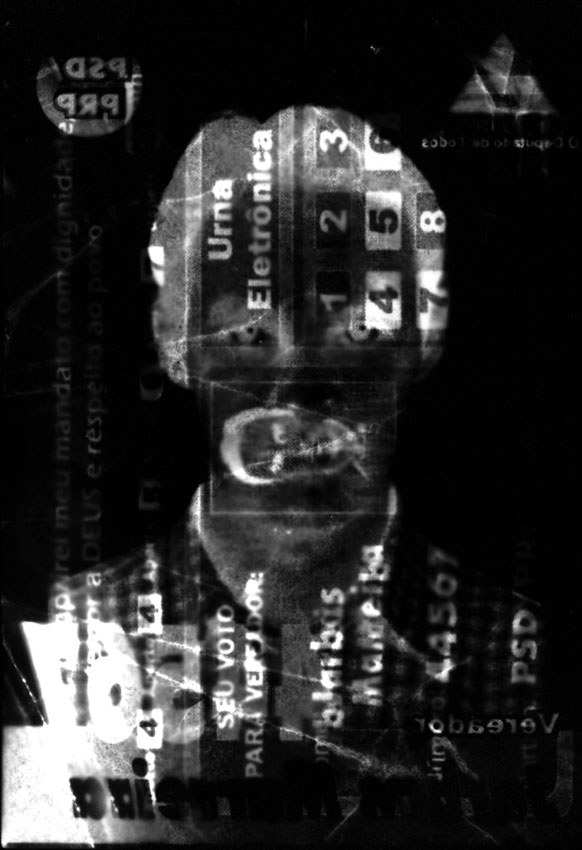

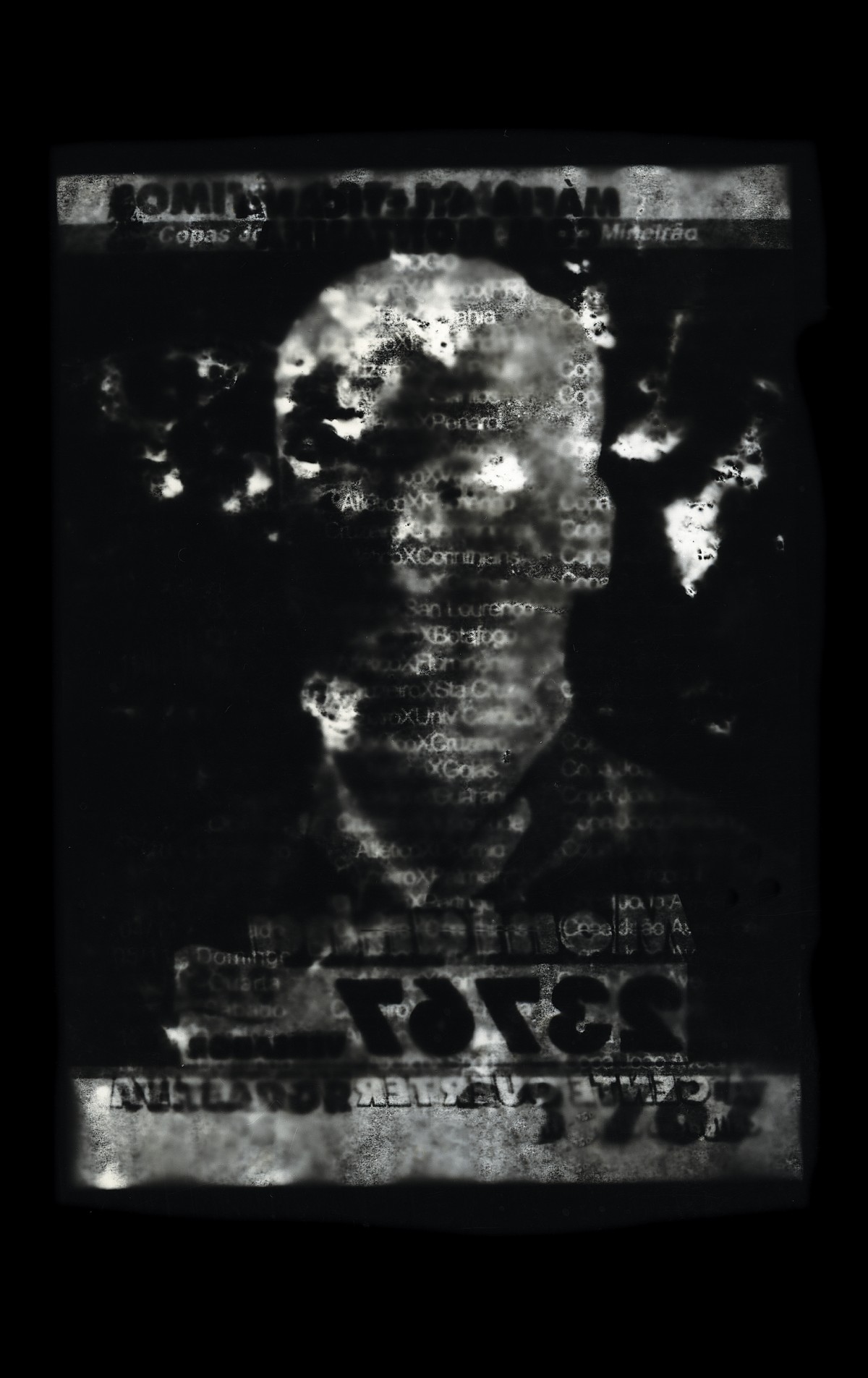

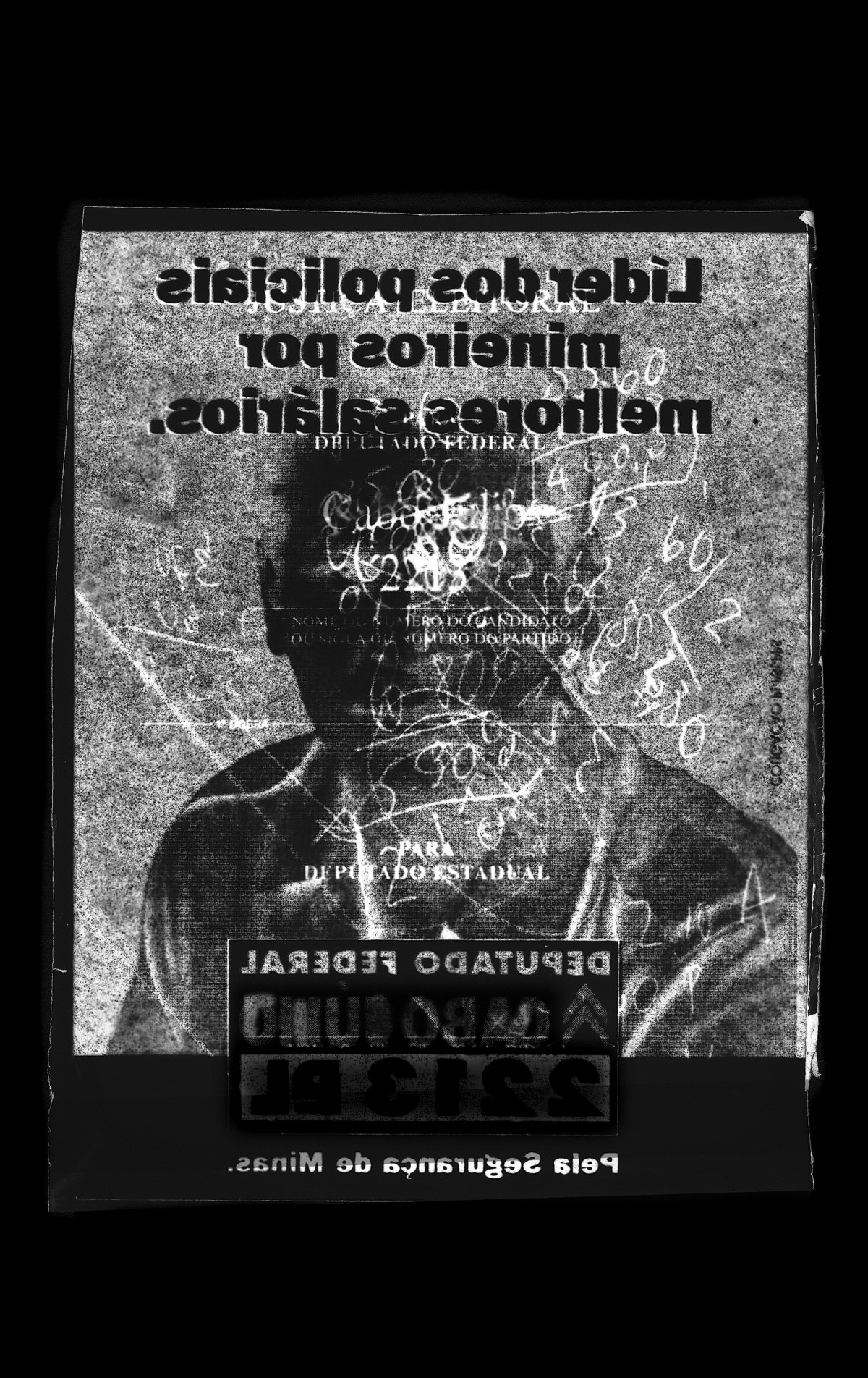

More straightforward pieces were no less effective. Dirty Saints (2002) is a brilliantly twisted series of portraits of politicians. She began collecting the tattered and decaying remnants of political leaflets that were littering the pavements during an election campaign.

By directly contact printing them in her darkroom she immediately rendered the relentlessly positive images in negative form. Further, the politician’s saintly smiles turned grotesque and their promises become tangled and impenetrable. Azevedo re-printed 16 of the ‘Dirty Saints’ portraits as alternative propaganda and literally returned them to the streets, handing them to passers by alongside the ongoing political campaigns.

Well now I had better come clean. Patricia and I hit it off immediately, as soon as we met. Not only did I love her work but also her passion for people and photography and art. Our friendship swiftly developed and within a few months we were working together (with her partner Murilo Godoy) on collaborative projects which are still ongoing 20 years later.

Some of our projects (and other partnerships she has undertaken, notably with Clare Charnley) have been published and exhibited, but Patricia’s early personal work has rarely seen the light of day, either in Brazil or elsewhere. Other people, especially, I suppose, influential curators and gallerists, just never seemed to get it, or perhaps they just haven’t seen it?

Her work was included in Novas Travessias, Contemporary Brazilian Photography at the Photographers’ Gallery, London in 1996, but her understandable concerns about losing the prints in transit, and mistaken insecurities about their diminutive scale led her not to show the one-off originals but enlarged copies instead. The hard truth is that these were nowhere near as beautiful as the actual work, in much the same way as the digital files displayed on a screen here can never do them justice either.

By the beginning of this century, some people, even some of her friends, started to wonder aloud why on earth she wasn’t saving herself a load of unnecessary hassle and doing her work on a computer, a comment so depressing and wide of the mark that it must have been extremely disheartening.

No doubt the lack of encouragement, as well as the lack of availability of papers, chemicals, time (she got a full time job lecturing in photography at the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Belo Horizonte), all played a part in her developing alternative ways of working and gradually letting go of her darkroom.

But the work remains, albeit in boxes in a cupboard in an apartment that suffers from the heat and humidity, so not exactly archival conditions! At least with these particular prints, there is the possibility that some mould may well add yet another layer to their depth and beauty.