From issue: #14 Environment

A review of Mandy Barker's STILL (FFS)

Written by Ricardo Reverón Blanco.

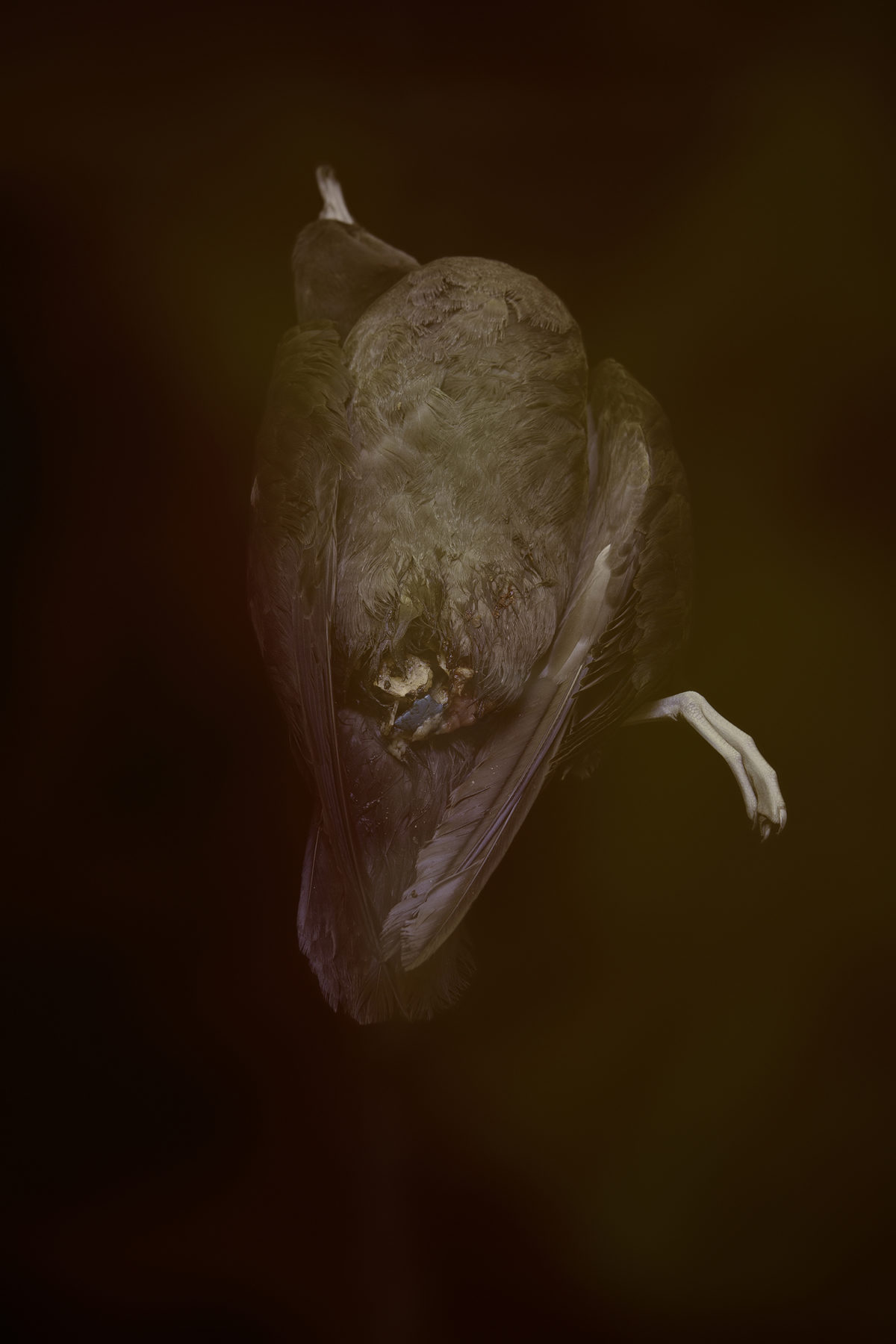

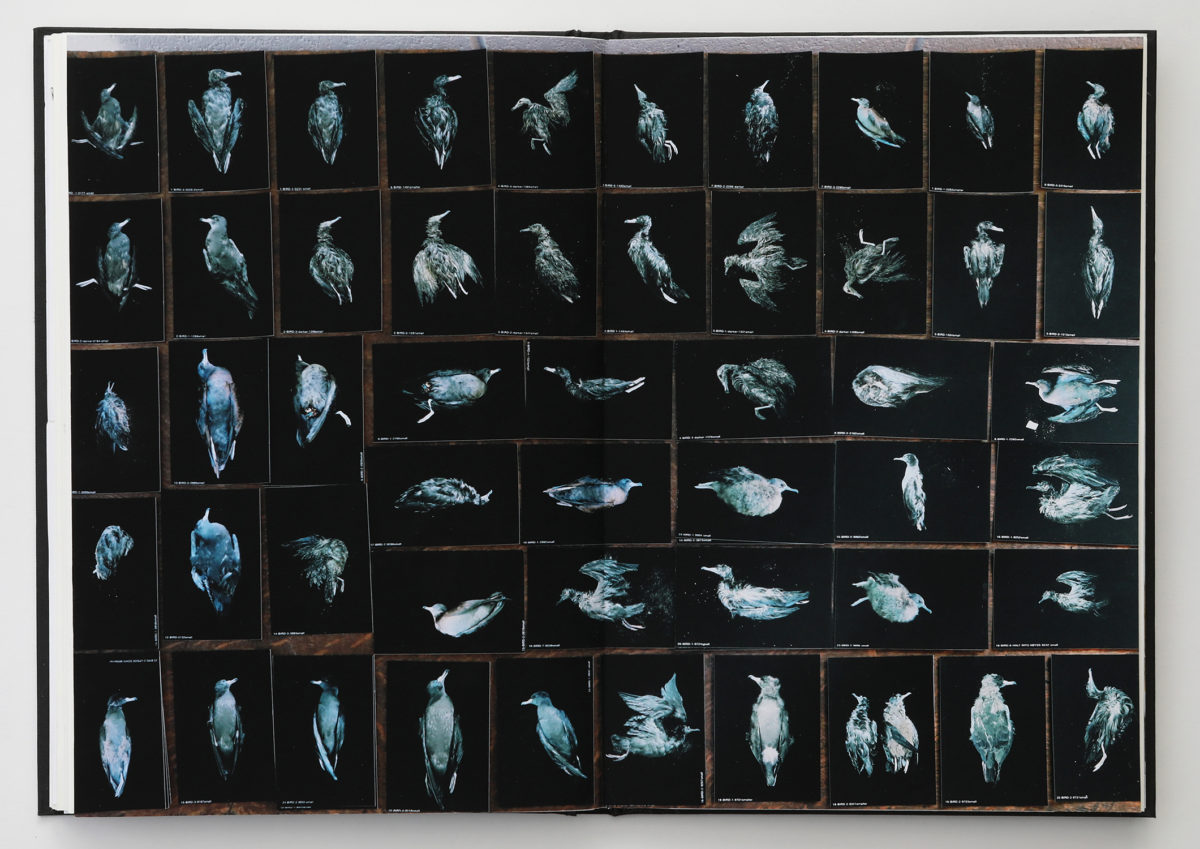

‘Dignified,’ ‘harrowing,’ and ‘inquisitive’ are the words that come to mind when encountering Mandy Barker’s newest body of work, STILL (FFS). Joining scientists on Lord Howe Island—600 kilometres off the coast of New South Wales in the Tasman Sea—in April 2019, Barker began studying the horrific decline of the local Flesh-Footed Shearwater population: as plastic foraged by the fledglings’ parents was fed to them as chicks, an entire generation starved to death.

Advocating for the end of climate change is a tough task, and we have yet to develop the appropriate verbal language to encourage environmental awareness. In 2021, it is clear that empty words and promises do not spur us into action. (To quote Greta Thunberg: “Blah blah blah”.) In Still (FFS), Mandy Barker offers us a photographic language that visualises the fatal consequences of this crisis and fosters dialogue around its immediate impact on life on Earth.

Using hints of colour, the artist manifests the blue seas and skies which a once-living Shearwater would have inhabited. Yet, gradually, the photographs shift to an all-consuming red, ultimately revealing the murder ‘weapon’: plastic found inside the bird during its autopsy. As the colours change from blue to red, the photographs’ faded backdrops become traces of living presence that has been taken from the now-lifeless Shearwater.

“My intention for this work is that the birds presented in this series that have suffered and died from ingesting plastic pollution will be seen around the world—and will serve as a legacy to the ones that have gone before them, and the others that will continue to do so.”

Mandy Barker

In Powers of Horror (1980), the psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva defines the abject as the horror caused by ‘[…] the loss of the distinction between subject and object, or between self and other’[1]. Abjection becomes the primary reaction when confronted with STILL (FFS) which— as Kristeva’s work helps us see—has the effect of reminding us of our own mortality. In Still (FFS), we are confronted with the experience of seeing the trauma of a perishable body and, consequently, our own eventual death is made palpably real.

The artist’s practice is thus a process deeply rooted in abjection; it presents us with evidence of life’s fragility and the possibility of its irreparable destruction. Barker isolates and frames the plastic extracted from the corpses of the Flesh-Footed Shearwaters, creating images reminiscent of forensic photographs taken during a crime scene. The series becomes a thorough case study of the climate crisis, and the images become the data necessary to sentence us for the murder of Shearwaters—a murder only made possible by our incessant plastic (mis)use.

Akin to the albatross in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, the murdered fledglings now hang over our shoulders, making us question our acts of violence on this earth. The epic poem documents the arrogance of the mariner who murders an albatross without motive and who is cursed for his cruel actions. Barker’s series similarly explores humanity’s hubris. Although, we are aware of the consequences of plastic pollution, if we choose to look the other way when faced with the deaths of the creatures affected by our unethical environmental practices, we are no better than the mariner. Just as in Coleridge’s epic, humanity will only find salvation when we rightfully atone for our assault on nature.

[1] Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, Columbia University Press, 1984, p.3.

Ricardo Reverón Blanco is a writer, curator, and arts researcher. He is the co-founder of photography-based collective UnderExposed and is the Assistant Curator at Photoworks.

STILL (FFS) is supported by the National Geographic Society Grant for Research & Exploration. To view the whole series and much more of Barker’s work, please visit mandy-barker.com.