From issue: #15 Hope and Futurity

Images by Tee Corinne

Text by Charlotte Flint

In the spring of 1978, American photographer Tee Corinne began working on her remarkable photobook, Yantras of Womanlove: Diagrams of Energy. Following a profound heartbreak, Corinne described how she ‘began to have waking dreams about this book. It became like a lover for me through one of the most difficult winters I had known as an adult – sustaining me and giving me a reason to go on’.[1] Photography was a lifeline for Corinne, a source of comfort and hope, and she poured her heart and soul into image making. What emerged was extraordinary. Exquisite photographs showing endless interlocking bodies: entangled limbs, passionate embraces, caressing hands, never-ending kisses realised in limitless, cosmic compositions.

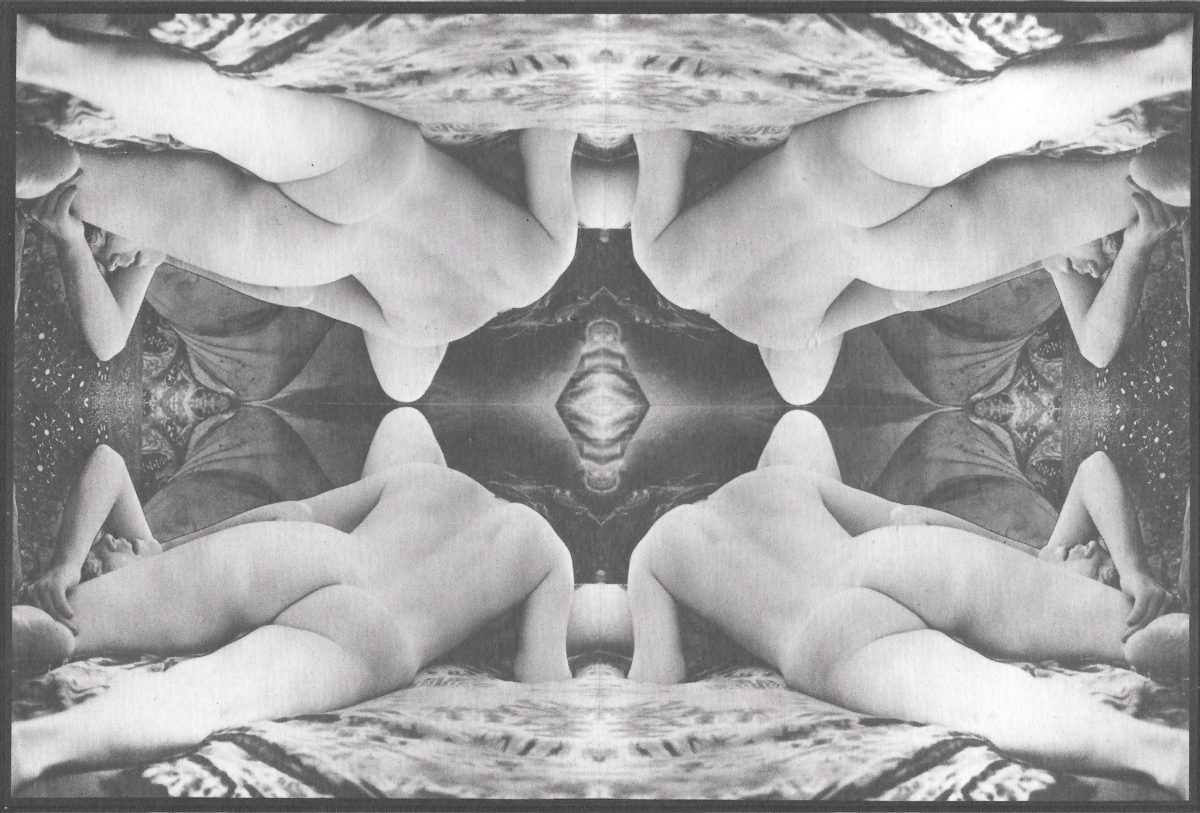

Published in 1982 by Naiad Press, one of the first publishers devoted to the circulation of lesbian literature, Yantras includes more than thirty black and white photographic collages showing women being sexually intimate with each other. Pieced together with extreme close-up shots of body parts, of flowers and plants, the results are dizzying constellations that lend themselves to slow looking, to decode what is being shown. Interspersed with stanzas from Jacqueline Lapidus’ poem Design for the City of Women (1977), Corinne took photographs of more than 60 women for the book and always aimed to represent the reality of lesbian society. Her artist’s statement describes her intention to ‘broaden the types of women who were included in sexual imagery, including fat women, disabled women, women of colour, and older women’.[2]

When I stumbled across Corinne’s work in the collection of London’s Feminist Library, I remember being floored by her joyous representations of queer love. In our current moment—when struggles for racial and sexual equality are further exacerbated by a pandemic and climate emergency—looking forward to a positive future feels increasingly challenging. Reflecting on Corinne’s work and the queer past at a moment of acute crisis conjures a renewed faith in the dynamism of the LGBTQ+ community, where fashioning our own way of life feels more important, and more politically necessary, than ever. Corinne’s work encapsulates ecstatic moments of eroticism which are simultaneously joyful and transgressive, political and hopeful, validating the existence of queer women and their lives. Her work depicts a loving community in which care, hope, and human pleasure are prioritised.

In addition to being an artist, Corinne was also a lesbian activist, sex educator, author, editor, and archivist. She devoted her photographic practice to the representation of lesbian relationships. Interested first and foremost in celebrating sensual intimacy between women, she produced a prolific number of photographs, many of which were used as illustrations in lesbian sex manuals, magazines and books. In part due to their explicitly sexual nature, Corinne prioritised having her photographs published rather than shown in galleries; she felt that ‘magazines and books offered a more effective way to reach a public which wanted to see the images, but which might not want to pay gallery prices or hang these images on their walls’.[3] Her dedication to erotic imagery was fuelled by a desire to highlight the beauty of women’s bodies and to empower women to celebrate the beauty of their vulvas. She asked ‘how [can] we teach women to enjoy sex if they felt that their sexual organs weren’t beautiful?’.[4]

This provocation led Corinne to make a series of drawings of vulvas, which she self-published as The Cunt Colouring Book in November 1975. Simultaneously, Corinne began to take photographs of women kissing and having sex which she decided to solarize, describing how the technique would ‘reverse some areas from positive to negative and produce a graceful, outlining effect where dark and light sections came together… [making] bodies look lit from within’.[5] From her original negatives, Corinne made new negatives which she solarized using Ortho film and Dektol, a developer usually used for paper prints. Almost all the images included in Yantras of Womanlove are solarized (a technique she also felt preserved her model’s privacy), and Corinne experimented with larger two-dimensional constructions using repeated images, creating glowing, kaleidoscopic compositions.[6]

In the book’s foreword, she explains the meaning of ‘yantras’ as ‘diagrammatic representations of fields of energy’ and that the book itself is about ‘the spirituality of sexuality, the transcendence that can take place when making love to ourselves and others’.[7] Rooted in joy, tenderness and love, Corinne’s work delights in the intimacy felt between women. While it celebrates pleasure, her work is also political, and she worked tirelessly to promote sex positivity and increase lesbian visibility, stating that, ‘the lack of a publicly accessible history is a devastating form of oppression’ which queer people face constantly.[8] In a society that has – and continues to – force queer people to the margins due to their sexuality, her revelatory work is a beacon of optimism and hope. In the introduction to Yantras, the civil rights activist and writer Margaret Sloan-Hunter shares a poignant reflection: ‘the frustrating thing for many lesbians is that most of these erotic images have been of the young, white, able-bodied and thin. While we continue to expand our sexual consciousness, it is important that our images reflect who we really are… I speak for the fat, black lesbian who at thirty-two was ashamed of her body, but who reluctantly agreed to be photographed for this book. She saw her image and smiled as she looked at the proofs’.[9]

Corinne continued to blaze a trail as a photographer, touring a slideshow of images of famous lesbians across the USA to ensure gay women across the country saw their lives reflected throughout history. She also co-established the Feminist Photography Ovulars in 1979-1982: low-tech photography workshops in the Oregon woodland where women were encouraged to explore their creativity and experiment with image making in a women-centred environment. Her practice encouraged viewers to reflect and take joy in their existence—at once referencing a rich queer history of photography, but also training the photographers of tomorrow to document moments of radical joy and eroticism.

In the introduction to Yantras, Corinne describes the kaleidoscopic images as, ‘patterns that grew like snowflakes, like the sound of rain, [which] still surprise me… full of details, running on and on, overflowing’. These surging sequences of passionate bodies continue to transform, tessellating and respooling through an endless spectrum. In a moment where community, hope, and solidarity feel distant, Corinne’s photographs glow with a different intensity. Beautiful, tender, and celebratory, they are a testament to the enduring power of love and intimacy.

[1] Tee Corinne, Yantras of Womanlove: Diagrams of Energy (USA: Naiad Press, 1982), p.7.

[2] Tee Corinne, ‘Artist Statement’, Lesbian Photography on the U.S West Coast, 1972-1997: https://cla.purdue.edu/academic/rueffschool/waaw/Corinne/CorinneStat.htm

[3] Tee A. Corinne, ‘Artist Statement’, Lesbian Photography on the U.S West Coast, 1972-1997: https://cla.purdue.edu/academic/rueffschool/waaw/Corinne/CorinneStat.htm

[4] Tee A. Corinne, Intimacies (USA: Last Gasp Press, 2001), p.69.

[5] Corinne, Intimacies, p.67.

[6] Solarization is a technique which involves exposing a partially developed photograph to light, before continuing processing. The introduction of light can give the forms in the photograph an almost ‘halo-like’ effect

[7] Corinne, Yantras of Womanlove, p.8.

[8] Tee A. Corinne, Historical Note, Tee A. Corinne Papers, University of Oregon http://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:/80444/xv98508

[9] Margaret Sloan-Hunter, Introduction, Yantras of Womanlove, p.14.

This article was published in collaboration with Photo Oxford.