From issue: #14 Environment

Written by Tshepiso Mabula ka Ndongeni

Land epitomizes collective place-making. On land, different parts of nature come together for collective growth and prosperity, which ultimately nourish the rest of creation. It is the land that grants us home and yet, in South Africa, land represents historical injustice. Land and soil are the literal meanings behind the Nguni word, Umhlabathi. Umhlabathi conveys the metaphysical and spiritual connection between land and the people who traverse it. It is also the name of an intergenerational photography collective based in Johannesburg. The group is made up of eight photographers who have made it their mission to document and reflect the struggles and triumphs of Blackness in neo-colonial Africa: Jabulani Dhlamini, Lebohang Kganye, Andile Komanisi, Tshepiso Mabula ka Ndongeni, Tshepiso Mazibuko, Sabelo Mlangeni, Andrew Tshabangu and Thandile Zwelibanzi. In 1913, the land our forefathers called home was unevenly divided and demarcated to keep the Native out and keep the coloniser in. The Natives Land Act of 1913 (later renamed the Bantu Land Act) sought to restrict Black people’s ownership of and access to land, except as employees of a white master. This history undergirds the lack of access that many Black people in South Africa still face when seeking to create space for themselves.

What does this history mean for a group of people building a place, a home, for Black photography? What does the work of Umhlabathi Collective—based in a basement in Newtown, the artistic hub of Johannesburg—mean for an art form complicit in the oppression of Black people? The Umhlabathi Collective seeks to build anew from this history, to find redemption for photography in a city of people unseen and unheard. This is why the building in which we are housed—on 2 Helen Joseph Street—is so important: it used to be the home of the prestigious Market Photo Workshop where all our collective members were either students or trainers. We each have an affinity with this building, which none of us truly own. It is here that our eyes were opened and where our political consciousness found an outlet. We strive to make this an intergenerational space that gives and grows, just like the land and soil after which Umhlabathi Collective is named.

The photographers who make up the Umhlabathi Collective are brought together by a shared vision: to collaborate, experiment with, and transform photography in relation to issues of representation, marketing, and dissemination through media and exhibition. The Collective’s studio has space for artists to work individually while also collaboratively building a home for photography in Africa. The space also houses important resources that will benefit photographers from all areas of society. The dark room, gallery, and digital and printing spaces are being renovated to ensure that the Collective has an in-house production space that will allow us to produce work that helps us question our society without limitation.

Umhlabathi is home to those who use photography—at times, an oppressive tool used for the surveillance of Black people—as a tool to document and grant the stories of Black people space, time, and respect.

In Johannesburg—which rests on land that has long been held in colonial hands and where ownership of land is only for the few—Umhlabathi seeks to create a place for sustainable and equitable growth, where arts education, resources, and creative space exist for the benefit of the many.

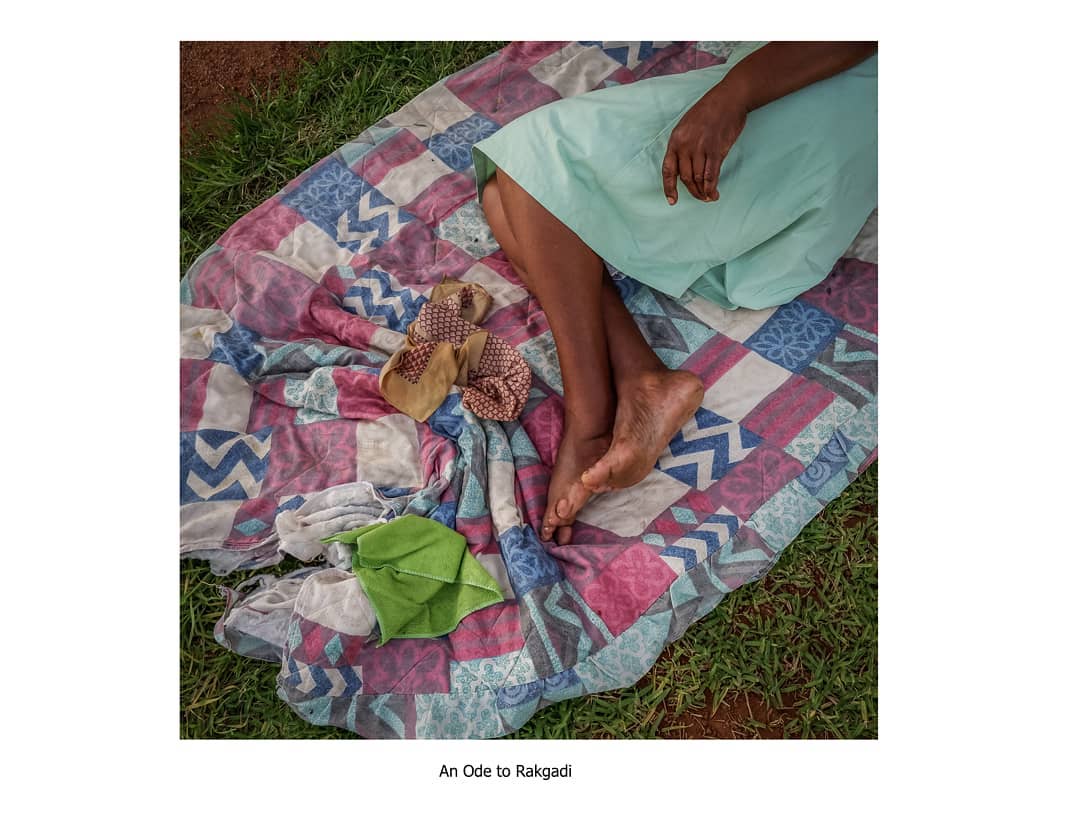

In a place like Johannesburg, where many have come to try and build a meaningful life, photography is labour. In the same way that the soil’s fertility depends on the laborious task of cultivation by dedicated hands, documenting the lives of the unseen labour force of Johannesburg requires the same sense of diligence. Each photographer in Umhlabathi Collective uncovers stories that make up the fabric of South African society, but which often go unacknowledged. For instance, when we speak about the impact of capitalism on the land, we tend to leave out the stories of the vulnerable people who are forced to work under harrowing conditions. Umhlabathi Collective exists to tell these stories, which we’re so often prevented from hearing.

The work of Umhlabathi is a considerable archive of the history of labouring in Johannesburg. The work—presented as part of the 2021 Joburg Arts Alive Festival and developed in conversation with independent curator, Thato Mogotsi—will be shown at the Umhlabathi Gallery in Newtown. The exhibition, which runs from November 26th to December 13th, 2021, is titled Vul’ Umhlabathi, which loosely translates to mean ‘open up the land’.

This exhibition consists of works that engage the idea of Johannesburg as a home where inhabitants grow roots. The work reflects everything from the unnamed labourers who built a city of gold to Johannesburg’s largely inaccessible wealth and prosperity. The exhibition and public talk will foreground the role that photography plays in archiving and humanising the Black lived experience in South Africa, despite the historical erasure perpetuated by oppressive systems.

We disrupt the land to build, to sow, and to extract its yield and partake in the fruits it bears. Perhaps this act of disruption by Umhlabathi, which aims to transform the way photography is created and consumed in Africa, is necessary for the growth of a new kind of labour in Africa and beyond—a labour that allows for true equality to be realised.

To find out more about the Umhlabathi Collective’s upcoming exhibition, click here.