The editorial in the current issue of Photoworks Annual and the short essay I wrote for the Jerwood Encounters: Family Politics gallery guide make a similar point regarding their shared theme of ‘Family Politics’.

Two forms of politics are potentially at play in family photography and decisions to prioritise one over the other result in a third.

The first is inward-looking, concerned with the dynamic of the family unit and relationships between its constituent members. If it involves an interest in a social world beyond, this exists mainly in terms of other family photographs. Family and photography are understood as discreet and self-contained worlds, the one sometimes shaped by the other.

The second looks beyond the family and photography, using each as the lens through which wider socio-economic forces can be brought into focus: in terms of class, religion, nation and so on. According to this view, the world of the family is part of a wider social fabric from which it cannot, or should not, be separated.

The majority of the photographs featured in Photoworks Annual and the Jerwood exhibition guide have the potential to be read both ways. Photography is a slippery medium, with meaning inevitably contingent on various factors. But this should not prevent us from trying to better pin down the politics of the specific projects.

By and large, the folios featured in Photoworks Annual belong to the latter group: considering family in relation to wider social, cultural and economic issues. So John Clang studies the effects of globalization and digital communication technologies; Dennis Yermoshin looks at national identity, displacement, immigration and community; Broomberg and Chanarin’s Holy Bible teases out links between the state, religion, photography and family as parallel system of authority and control; and David Moore studies the socio-economic landscape of Britain under Thatcher.

The majority of artists featured in the Jerwood exhibition belong to the first group: concerned with the family unit and photography as discreet fields defined through their relationship to one another. So Jonny Briggs uses photography to explore his own family history and the condition of remembering; Joanna Piotrowska restages family photographs in ways that render them strange and uncanny; and both Nikolai Ishchuk and Robert Crosse display suspicion towards the staged performance of happiness for the camera.

The Jerwood exhibition was selected from over 300 submissions. Given this large number, a whole range of potential exhibitions can be envisaged; alternative routes mapped; emphases placed elsewhere. The following brief notes suggest one such alternative, in which the focus is placed squarely on the second, outward-looking model of family politics.

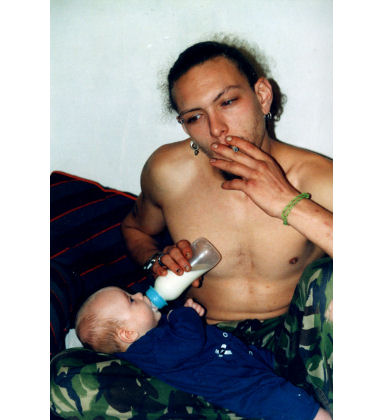

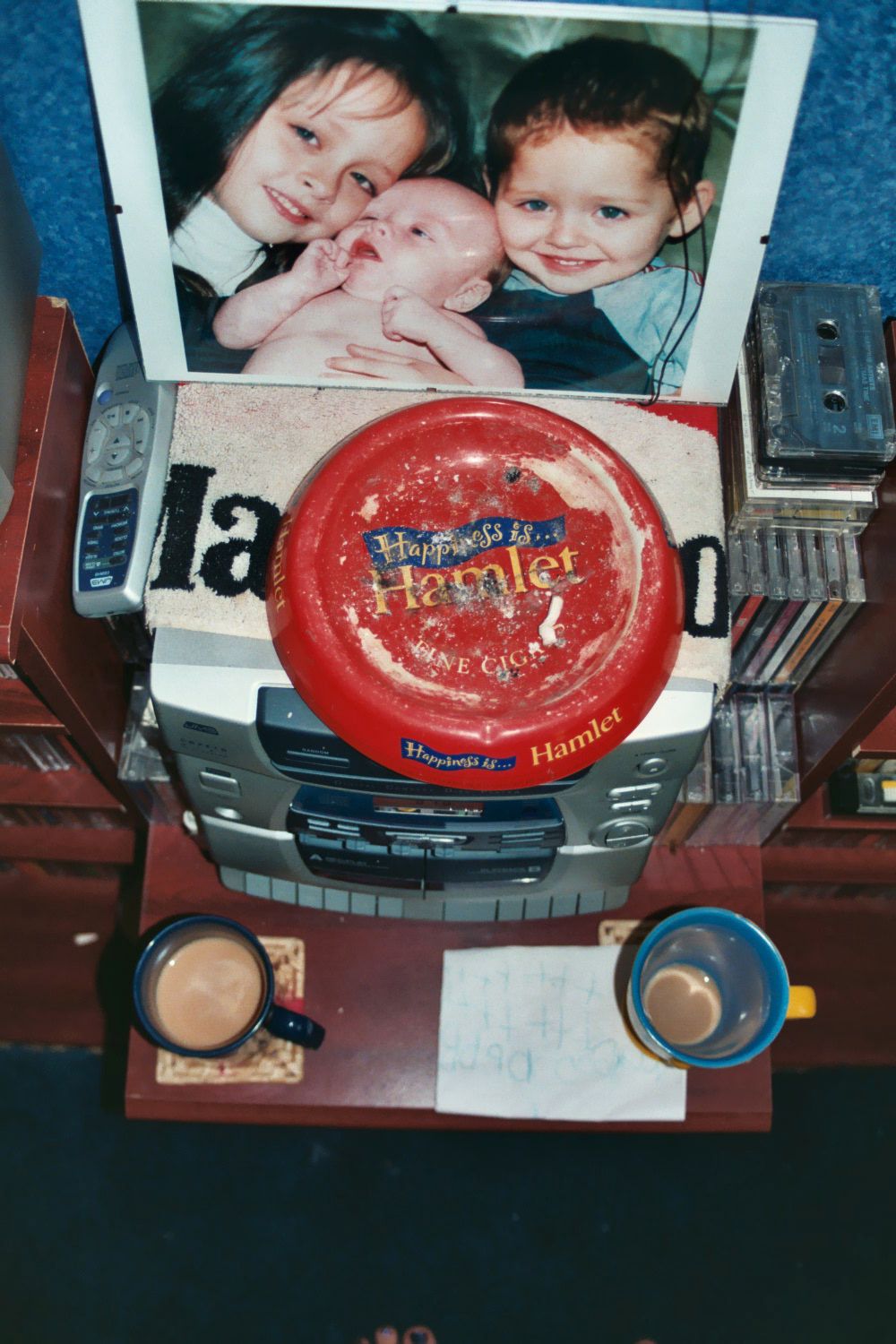

© Emma gates, from the series Living with Benefits

Emma Gates’ series, Living with Benefits provides an intimate study of life lived on state benefits, premised on an oscillation between the confirmation and questioning of media stereotypes. On the one hand, we are shown the clichéd signifiers of the lumpenproletariat: ashtrays and fag buts, piercings and beer towels, each starkly illuminated with flash.

These aspects exist in tension with the affection with which the subjects are represented, the performative nature of the portraits, the heightened theatricality of some of the images, and the formal order and general tidiness of some of the scenes. These elements help resist the patronising and voyeuristic potential of the photographs: we sense agency and collaboration in the subjects’ performance and play.

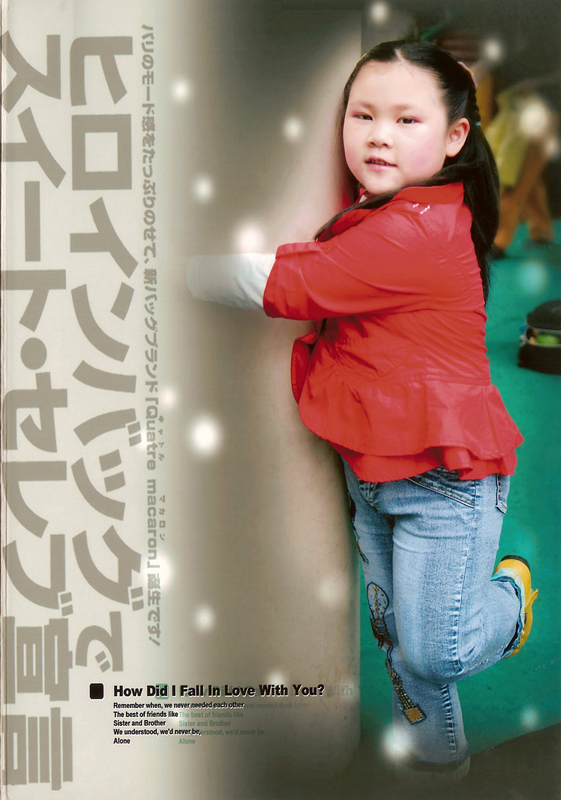

© Bruno Zhu from the series the baby smiles to be like the angel similar

Bruno Zhu’s series, the baby smiles to be like the angel similar uses facilities available in a commercial Chinese portrait studio to produce image-text works involving his younger sister. The poses in the photographs feel exaggerated and strained. This creates a sense of excess, heightened by the intensive post-production and the inclusion of text.

The young girl is shown as a princess, an angel, a graduate, while the texts suggest different narratives: creating a dark parody aimed at subverting the roles imposed upon young women of different ages. Printed on soft-paper and glued directly to the gallery walls, the links with advertising are made explicit. Zhu points to the relationship between expectations that shape the family and reductive templates of femininity maintained by commercial culture.

© Maria Kapajeva from the series I Am Usual Woman

Maria Kapajeva’s two series, I Am Usual Woman and Birch Trees of Russia, also examine relationships between family and commerce, focusing on the place of photography in the trade of Russian mail order brides. I Am Usual Woman is a quilt made using photographs drawn from matrimonial websites, stitched in collaboration with the artist’s mother. It uses the “Double Wedding Rings”: a traditional Western pattern designed for wedding quilts stitched by brides’ mothers or female relatives.

© Maria Kapajeva, Birch trees of Russia

Birch Trees of Russia presents a selection of images from the women’s web profiles. The photographs all show women standing next to a birch tree: one of the main symbols of Russian culture, which Kapajeva discovered was included in almost every woman’s profile page. The selection of images is shown as a slideshow, accompanied by a Russian pop song called Birch Trees of Russia. Through the repetition of the birch tree, and the tragi-comic relationship of photograph and music, Kapajeva draws attention to its role in confirming the woman’s ‘Russianness’ for the sake of Western male viewers/consumers.

© Photo Greenland

Jan Lemitz’s ‘Local Business Study – Photo Greenland’ focuses on a family business run by two Eritrean bothers, operating out of a small store in the Neve Sha’anan street market in Tel Aviv. The main revenue of the company comes from wedding photography and videos. The photographs displayed in the installation show portraits of young men on weekend outings and families during religious holiday or weddings. These are moments of diaspora life that offer insights into the enclosed community of Eritrean refugees (whose social and political status is comparable to that of refugees in the EU).

The planned installation of the work would combine a selection of the work of Photo Greenland, a documentation of the company’s working process and the locations this involved. Writing about the project, Lemitz explains, ‘Photography appears as a practice that is operated regardless of status. As such it allows operation within autonomous networks that momentarily undo what governs the boundaries of belonging to and exclusion from formal frameworks.’