Over the last 15 years, kids have been central to my practice. Playing with kids is always fun. Doing this on a regular basis and making it your profession makes you feel somewhat invincible, like a character in a game with unlimited lives.

For many years, I have involved kids in the process of my work, teaching them a few things that I know and understand, showing them possibilities, pushing their creativity and in return I learn what life could potentially be – if it was not for society’s urge for law and order.

Kids and youth have an overall energy that is beyond that of any adult. All that is sacred stems from youth: dedication, naivety and honesty. To me this is the greatest inspiration that only a few grown people in the world can give me and nearly every young person seems to be able to deliver such energy, free of charge and without hesitation.

I have managed to build a solid career as photographer on the basis of playing and conceptualizing games all day for a vast variety of issues, clients and things. With that approach, even the most difficult subject matter becomes just a game to play in my or our mindset. Once you accept the rules and visions, everything becomes possible and no problem lasts for long – at least within the limitations of the game. Once it is won, we have to find a way to translate that into some kind of reality (in my case a photograph) and there we go: we have a solution to offer – sometimes practical but mostly abstract and fun. The latter seems most interesting, as viewers are given yet another riddle or game to play with, which is so neatly constructed that it can be easily won by the target audience. When all this happens, then I have won too and can proceed to the next issue. All this is my credo and this is what I practice: nothing is impossible in my worlds.

Obviously it is not as easy as it sounds. It takes a lot of research, testing and failing to do what I do with my team and all the people I play with. They are not only kids, but also a good number of open-minded adults. And it surely takes a few skills in clever management, networking and funding to make it all go round.

Looking back at my most recent major project, The Amazing Analogue, which I was commissioned for the Brighton Photo Biennial 2014 in conjunction with Hove Museum, I feel that I was able to construct a photographic game, which we can all play together. Due to the common theme of the BPB 2014 ‘Collaboration’, the key element this time is documenting the process and making it the piece itself.

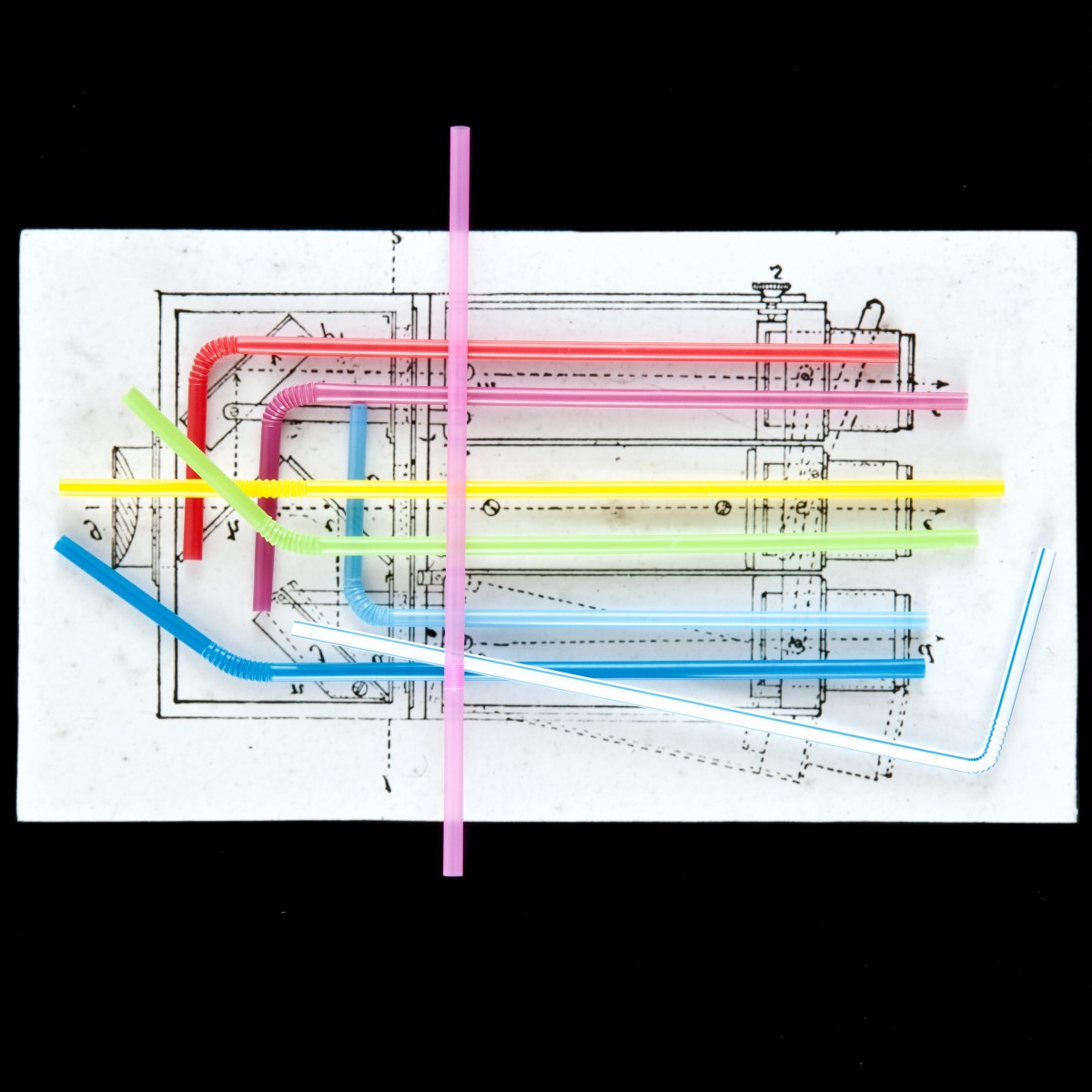

My initial brief was: take a group of kids, a museum’s collection of films, cameras and images from 100 years ago and make a workshop that can result in an exhibition. We found some boxes of photographic slides that dated back to Victorian times and the area of Brighton and Hove. Only a few years back, they were donated to the museum by a generous old man who didn’t know what better to do with them. Nobody from the institutional staff had yet even looked at the images in detail. They were still a mystery yet clearly indexed to become a vital part of the museum’s collection.

A brief glimpse into the set of about 150 images showed the kids and I that this was our starting point for the project. We were all amazed about what we found and curious to figure out their content. The images were puzzling as they seemed quite random, yet, they had an abstract potency which was timeless yet questionable. We found no obvious common theme or particular authorship. We couldn’t figure out what they meant and what they had been taken for.

So we started collecting clues. We studied the photographers that seemed to have taken those images. We looked at all the machinery that might have produced such visuals and we researched the time and place that surrounded those images. Over the period of the workshop sessions within the museum, we achieved a very good understanding of what the environment must have been for such images, yet we still had many questions left unanswered.

So what’s the current state of science and society for weird questions? You put them into a machine and respect the given results. However we didn’t know of such machinery for the demanded purpose.

Our next step was obvious to all of us in the team: building the machines we needed simply ourselves (including techniques and machines from the Victorian period, that had produced such imagery in the first place – clearly we implicated modern and more advanced technology in order to improve the apparatuses). Then putting the images in question through the machines and waiting for them to be processed.

What came out of them? Well… I’m not really sure what it is. But it all looks very beautiful and even the machines become pieces of fine art technology.

–

Jan von Holleben’s exhibition Amazing Analogue: How We Play Photography will be on display at Hove Museum and art Gallery from 4 October 2014. Fore more information visit bpb.org.uk/2014