In issue 8 of Photoworks magazine, David Campany looked at John Stezaker's work.

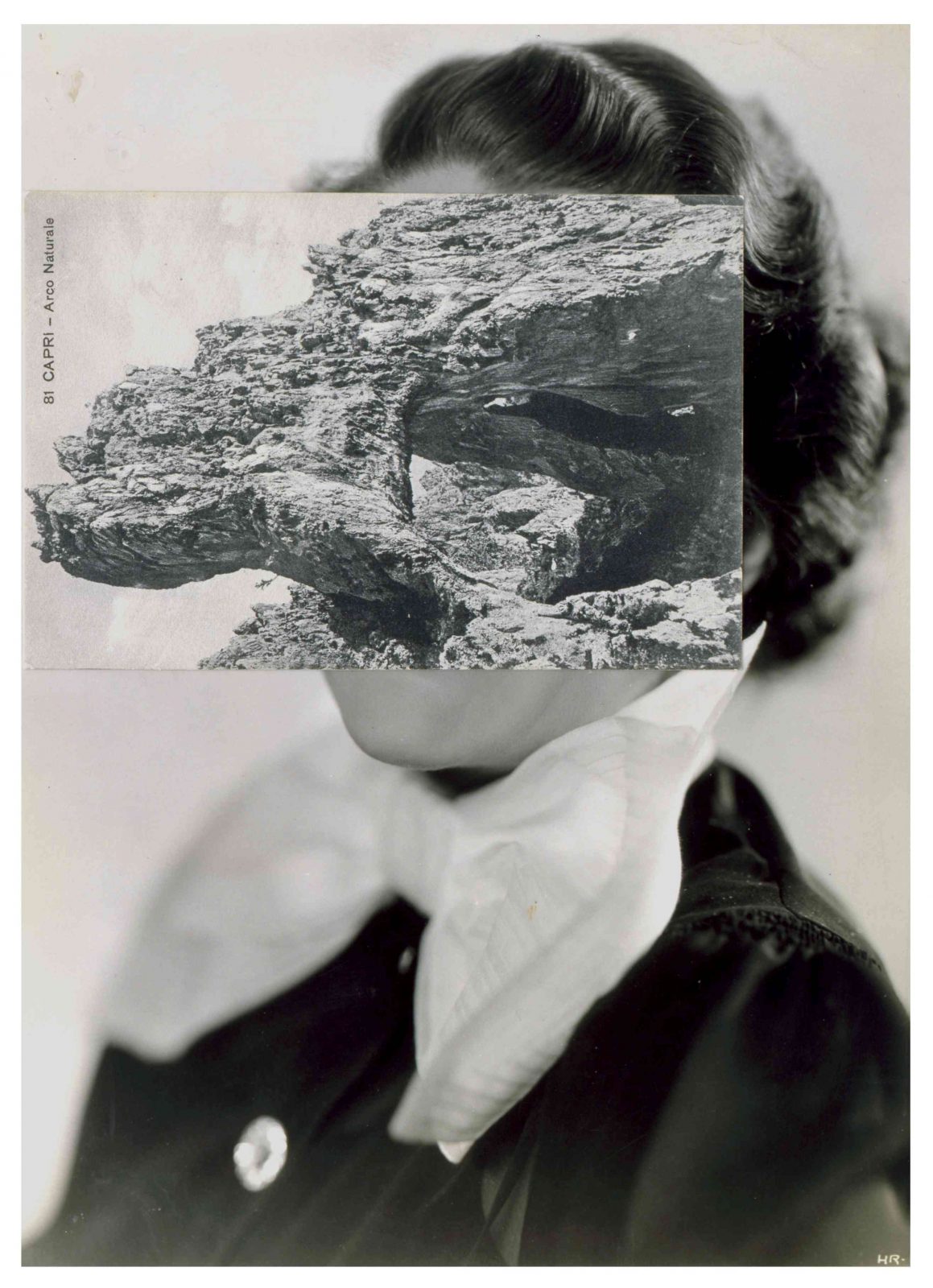

I have no idea how John Stezaker makes his art. This may seem odd given that it is patently clear he works with the collage or montage of appropriated imagery. What I mean is that I cannot tell how he has arrived at his choices, either of image, or cut, or combination.

My first impulse is to see in his art something of dreamwork that Freud laid out so well in 1899. For the dreamer space and time do not obey the logic of shared waking life. The unconscious may displace and condense wildly different fragments of experience, splicing them seamlessly into an imaginary whole according to some hidden logic. The raw material for the dream may be as likely to come from deep in the past as from ‘the day’s residues’. The dreamer involuntarily sifts and reconfigures the bits and pieces that have left their ineffable impressions upon the mind. Such a reading is somewhat confirmed by the nature of Stezaker’s source images. Many are film stills: washed-up fragments of long-forgotten movies from the collective dream factory that was Hollywood’s heyday. This would make Stezaker a re-dreamer, of sorts.

[ms-protect-content id=”8224, 8225″]

Perhaps the analogy is too obvious, missing what may make these collages fascinating either for us or for Stezaker. They may have emerged from another state, somewhere much more awake, perhaps too awake. Insomnia may be closer. Perhaps the artist cannot get to sleep because the images that fascinate him also worry him. For the insomniac the world becomes, as Chuck Palahniuk put it, a copy of a copy. It is unnervingly real and vivid yet disorientingly unstable. Form and shape and surface insist but meaning seems to slip and slide. In this Stezaker’s work touches on the anarchy implicit in all images. Photographs in particular are possessed of a wildness usually tamed and controlled by texts and contexts. Like children, photographs need boundaries in order to ‘behave properly’. Remove them and all manner of demons are let loose. Cutting the image lets loose more, and joining two parts together more still.

All of this uncertainty is compounded by what looks like the dead certainty of Stezaker’s technique. His cuts and joins seem so precise, so surgical, so minimal, as if they are the only ones that could have been made. They offer us the poise we need to set out along the highwire of interpretation. Below lies the abyss between the banality of images and their shifting possibilities.

Montage and collage are usually thought of in terms of addition or assembly, and there is no denying that Stezaker’s works bring together two images to produce third effects. Yet at the same time the psychological structure of much of his art is the gap or lack. One experiences a shortfall or vacuum every bit as unsettling as the overflowing excess of image collision. In putting things together Stezaker takes other things apart. Looking at his art we may feel we are being offered too much and too little all at once. It’s the kind of imbalance that can keep you awake at night.

[/ms-protect-content]