Danit Ariel, 02 May 2025

“Our sight is suffused with knowing, instead of feeling painfully the lack of knowing what we see. The principle to be kept in mind is to know what we see rather than see what we know”.

I received this Abraham Joshua Heschel quote in a text message from my father when discussing the boundaries of representation in photography. Heschel was not an image-maker, but a rabbi, philosopher, and civil rights activist who developed critical thinking around looking at the world with “radical amazement”, attempting to break through the clear water of our predetermined notions and ideas.

It is no surprise that we struggle to face what we are seeing or to remain aware that we are seeing at all. Though I am no scientist, theories like predictive coding have articulated how our brains predict sensory input, such as images, creating a mental environment which categorises the world around us. Inputs filter through this process, and we are then tasked with updating our models when experiencing a prediction error. Whether one puts more weight on their model or on the input at hand will, in some sense, indicate how actively they are looking. In other words – where do we place life that slips through our pigeonholes, when on the other side of a prediction error, there is often a human being who is experiencing the immense burden of mischaracterisation and objectification?

This is where representation in photography plays a crucial role in diversifying who and what we see, and who gets to share visual depictions of self, community and culture. But I worry that representation alone is not enough. The depiction of queer people for example, has often relied on the visualisation of queer stereotypes, which in turn creates a new set of norms around how queerness looks, and I am often left wondering where the queers are who look and live like me.

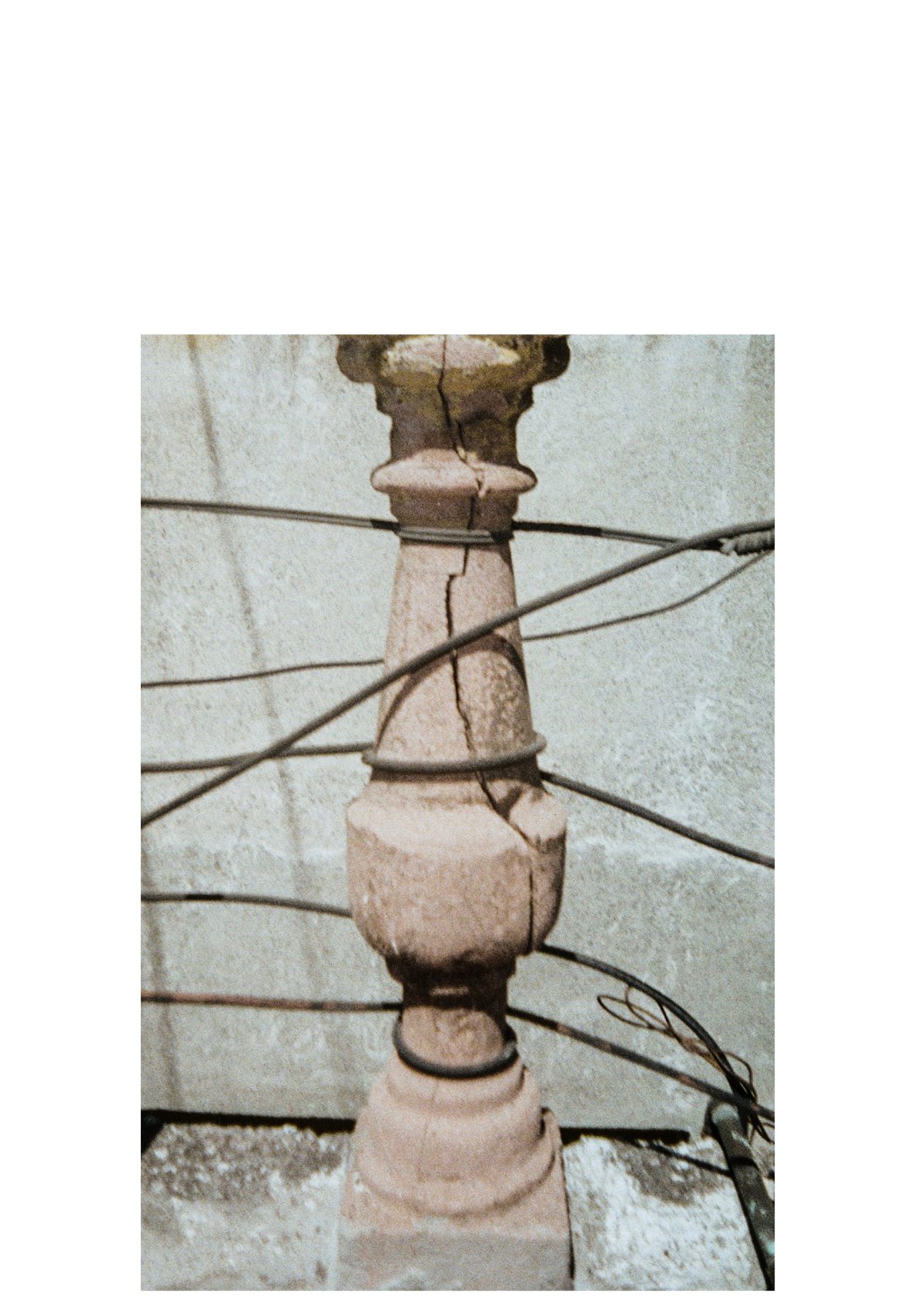

Naturally, I find myself drawn to photographic works that share the responsibility of reimagining society with the viewer. Pieces that use methodologies that make the surface of the image known to engage audiences critically, or those that leave physical representation at the door altogether and instead visualise the internal and intangible.

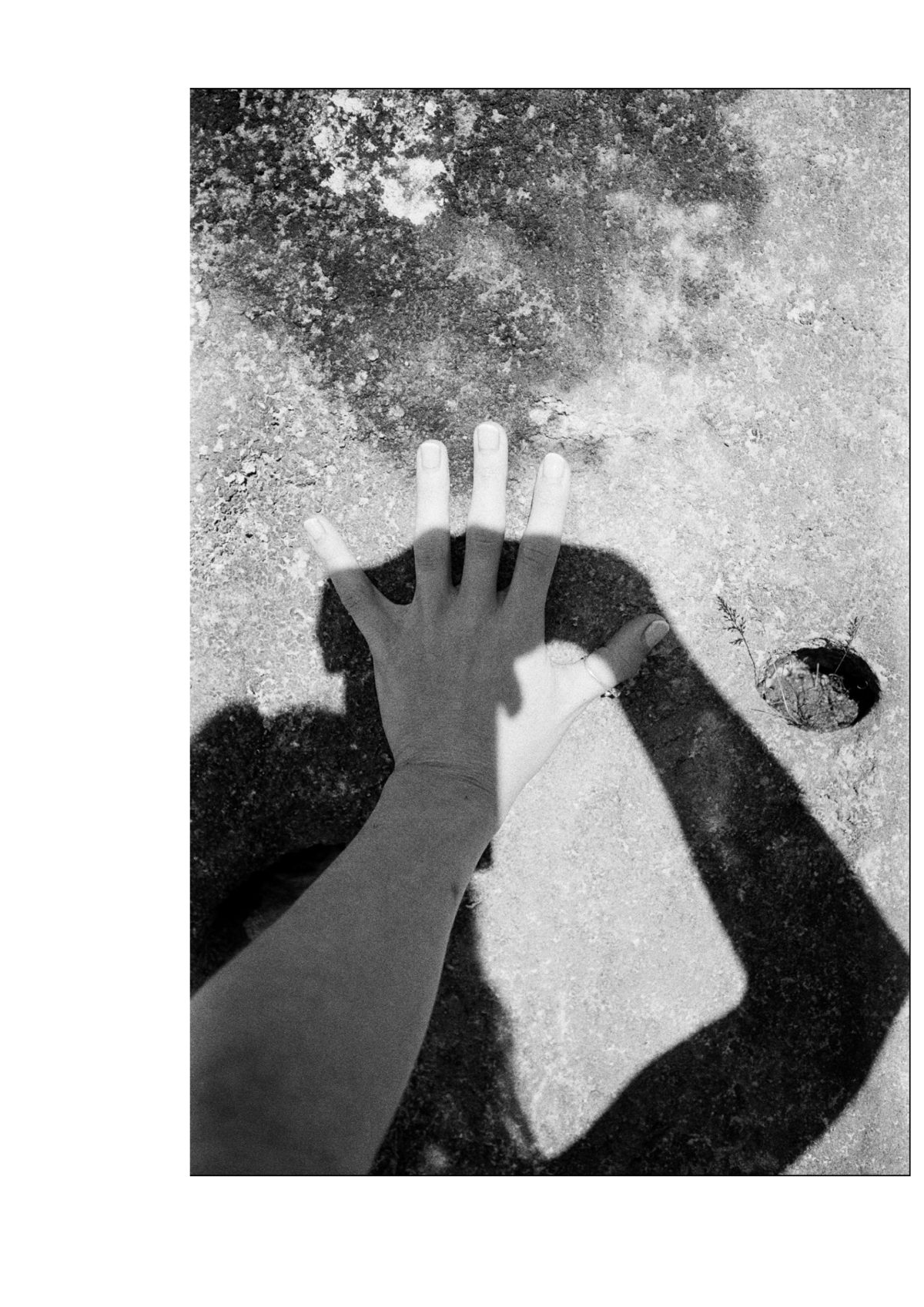

So much of life cannot be categorised. So much of humanness is heart and soul that will not fit into words or the frame of a photograph. And is art not one of the few remaining spaces that has the capacity to see people as more than statistics? Photographer Antonia Mayer addresses this in her practice by pushing back on the superiority of logic in the medium and society at large, to make way for the emotional realm. For the fluid and the in-between, that which does not require tangibility and instead accepts lived experience as proof of its existence. Catch My Breath, an autobiographical series exploring pregnancy unpicks the rigidity of male-centric textbook knowledge and sits comfortably in the unknown or the more than words can say. In fact, the need for linear pathways and solutions is rooted in patriarchal thought, but I digress. Catch My Breath not only depicts what cannot be seen but also assembles these snippets of feelings to emphasise that they are all happening at once.

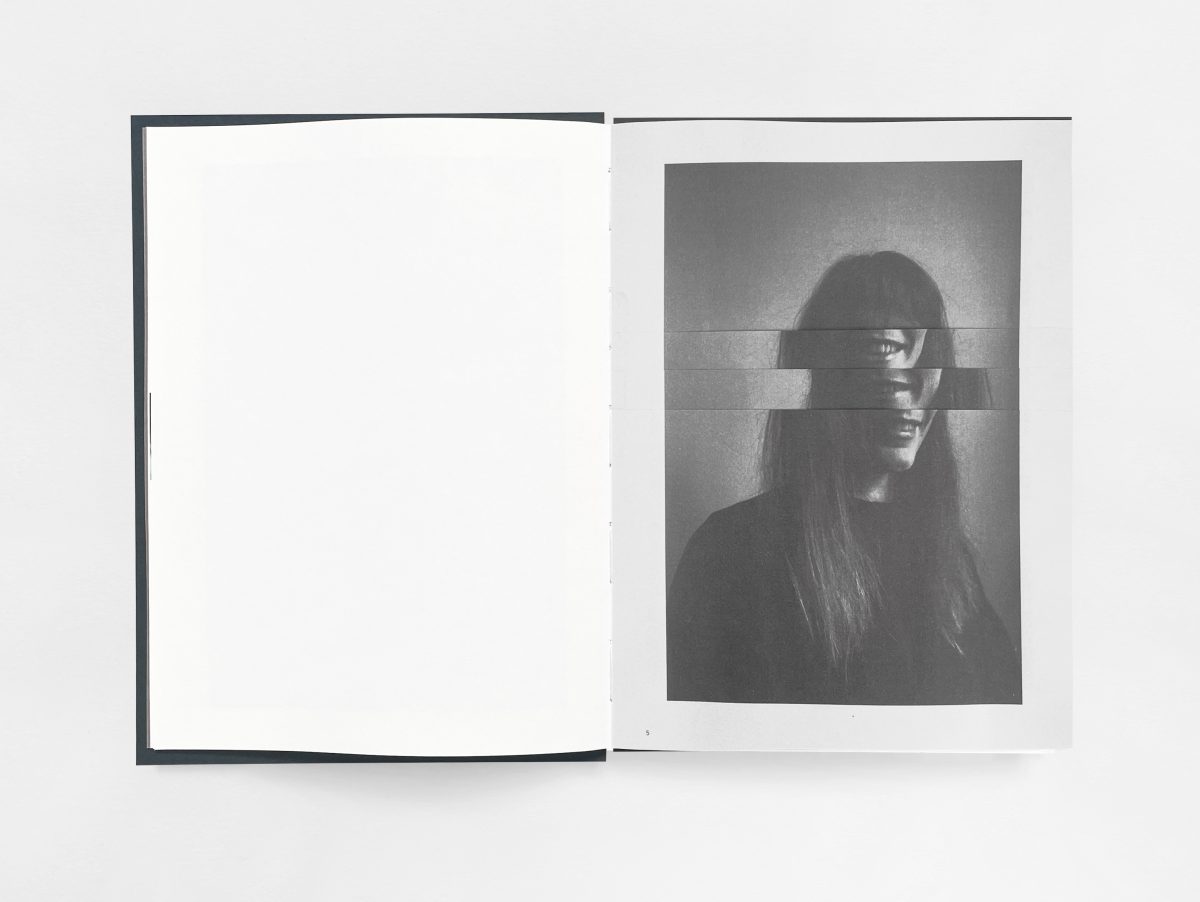

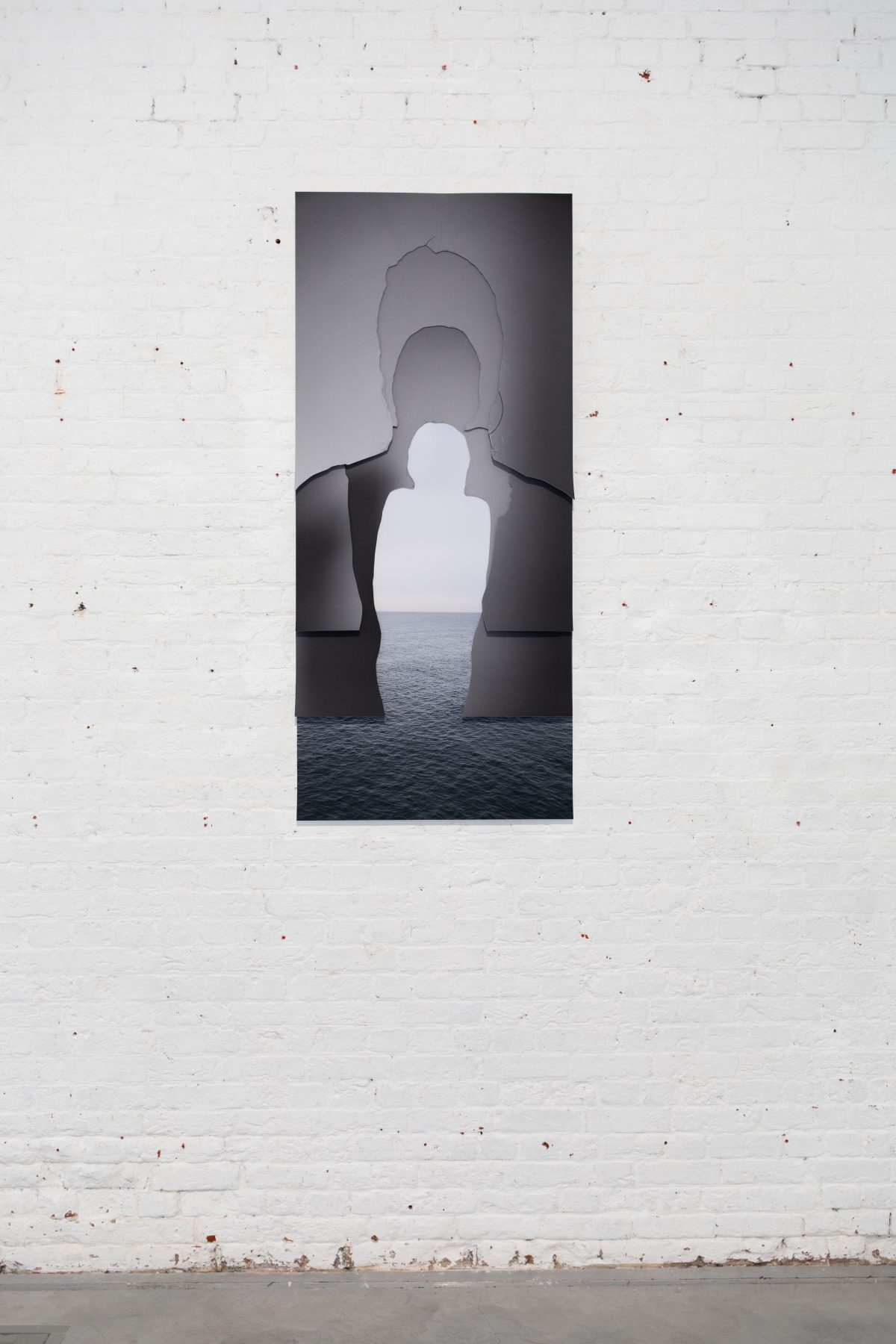

In her work, Sorry I’m Not Sorry, artist Lauren Joy Kennett approaches the part of us which relies on awe rather than knowledge. Sharing her experience of living with undiagnosed autism through fragmented and re-assembled self-portraits, employing both her inner world and the materiality of the image to be seen. Her piece Something is definitely wrong resists the typical form of the image, layering two photographs on top of each other and pulling down one of them to spill out of its own frame. Grace Martella focuses on the internal experience of being trans in her work “Memorie del transitare”, avoiding certain photographic cliches or relying solely on physical attributes of transness that can be perceived as resolved, and therefore put in a box, even if a new one.

These non-linear practices present expansive experiences and remind us that we are more than the sum of all our parts. That “stories move in circles… so it helps if you listen in circles. There are stories inside stories and stories between stories, and finding your way through them is as easy and as hard as finding your way home. And part of the finding is the getting lost. And when you’re lost, you start to look around and to listen.”– Deena Metzger.

What I seek in art and photography is connections, not conclusions. Attempting to develop an empathetic gaze, I find myself returning to an image of my mother that continually highlights the gaps between my desire to see images and the people they depict wholly, and the reality of projecting what I know onto photographs. Time and time again, I have to sit with this image for my mother to come into focus. At a glance, even if the hundredth glance, even if my mind knows I’m picking up a photograph, I still at first, see myself. It makes me wonder what other images I do that with, and whether I do that to my mother and not just the image of her. It makes me wonder who else I do this to and how open and on I must be to learn something new.

Perhaps then, the true responsibility I hold when gazing upon an image, is to allow myself the flexibility of not knowing or understanding right away. To treat the encounter as a first meeting. With curiosity and wonder and radical amazement.

Danit Ariel is an artist, writer and curator, whose practice looks into how art can create new ways of meeting. She is the author of Nayah: Empathy as an Act of Resistance which explores the role of gender in practices of empathy; and All the Tables are Brown, looking more specifically at language as both a bridge and barrier between communities. As Photoworks’ curator, she manages the curatorial programme and develops the Photoworks Festival.