From issue: #25 Multiplication

Angelina Ruiz, 6 December 2024

German born, UK based photographer Alma Haser is remastering the art of portraiture through her work. Growing up, she was surrounded by artistic parents; at age 13, turn a tin into a pinhole camera, and developing pictures in the bathroom, her interest for the medium began there. In her work, Haser incorporates collage, digitally manipulating photographs, focusing on pattern, texture and layering. Her use of mixed media recontextualizes her subjects, altering their form and shifting their gaze. Her fine art background comes across in each of her works, a careful and cautious hand that takes into account the minutiae of the human identity.

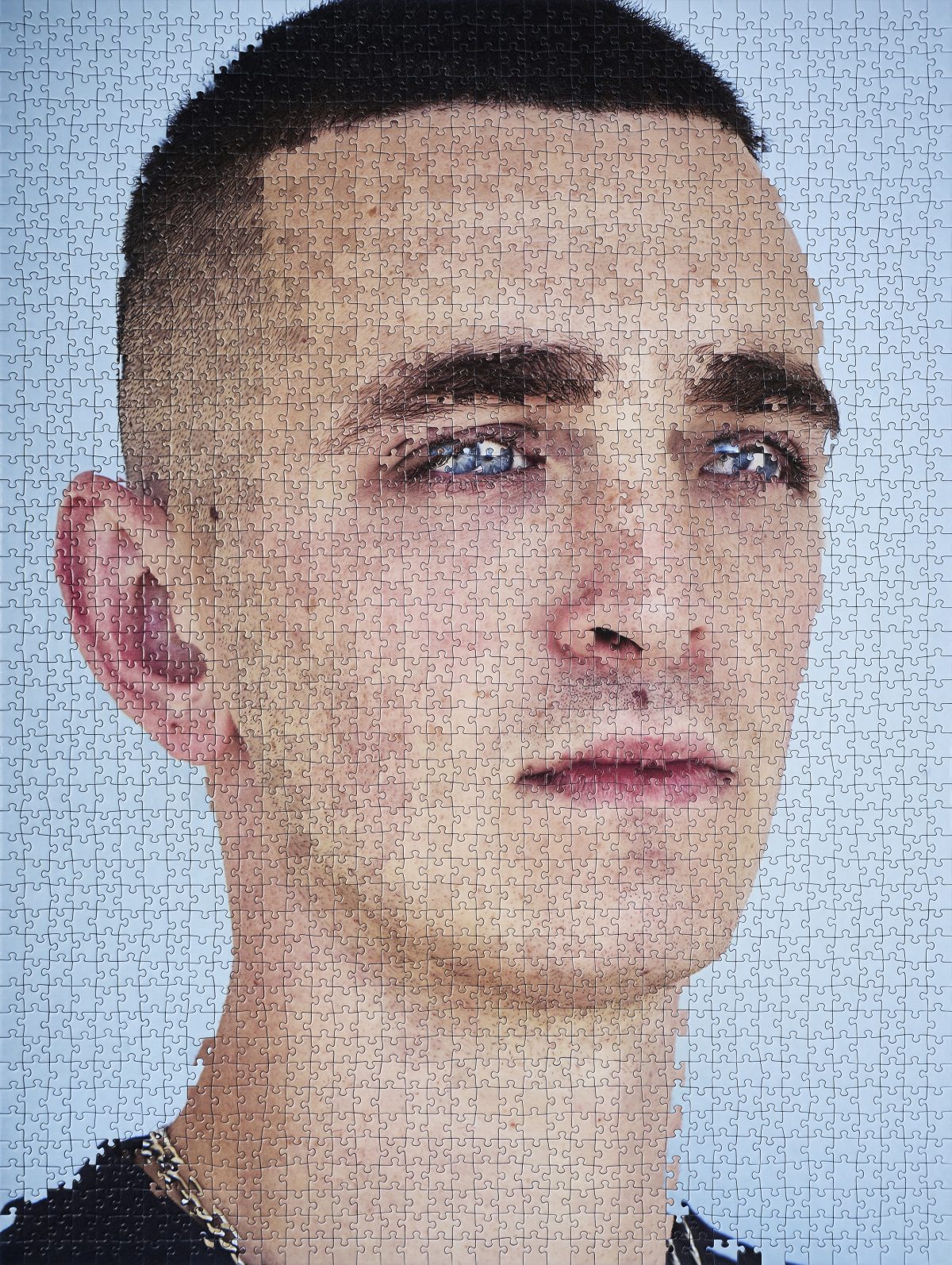

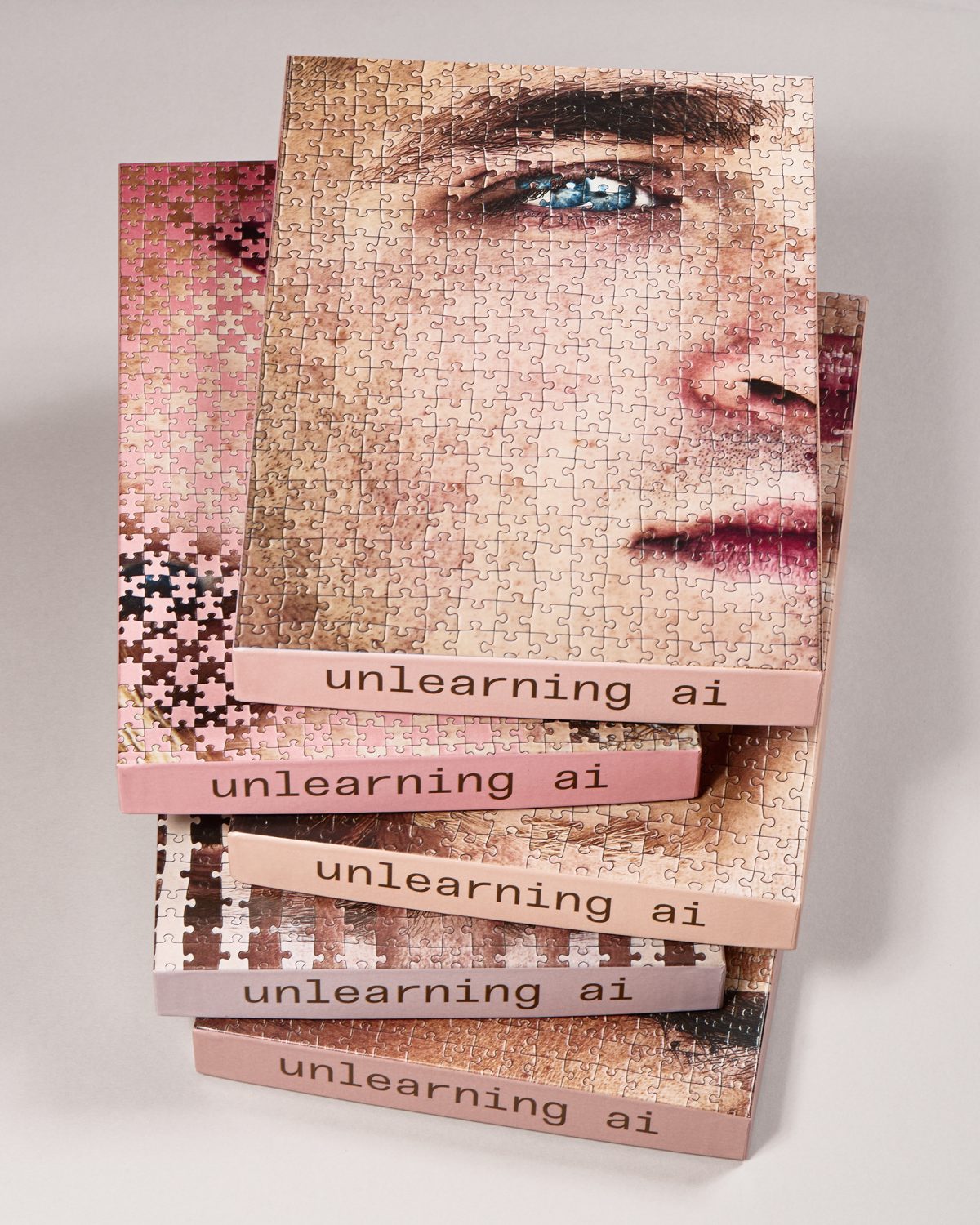

In her most recent and ongoing series, Unlearning AI, Haser creates her own kind of algorithm by combining jigsaw puzzle pieces together to make portraits, each with their own flaws and idiosyncrasies. The series includes five portraits, all of whom are people Haser originally photographed. She then meshes two 2,000 piece puzzles, reconstructing each of the portraits by hand, mixing and matching the features of each face. Each of them has a different kind of physicality, and Haser invites us to look at the seams and pieces of the puzzle, allowing us to be a detective searching for irregularities. However, these are not the AI generated portraits we’re accustomed to– ones that are unsettling and look almost too human, blurring our ability to tell what is real or not. Haser’s images embrace the flaws and excite us with their imperfections.

This way of working isn’t new territory for Haser, as she utilized puzzles in her 2018 series Within 15 Minutes, in which she explored identical twins and their genetics. When asked about this medium, Haser says that she was fascinated by it, as it allowed her a better way to get across her concept. She says: “I seem to always be drawn to mediums that take time, things like paper folding and manipulating, tapestry and embroidery too. I like the laborious and meditative qualities.” It’s the physicality of the puzzle that attracts her, and the almost monotonous, repetitive act of putting pieces together one by one. The medium allows Haser to interact with her work on another level, one that isn’t traditionally offered by photographic prints.

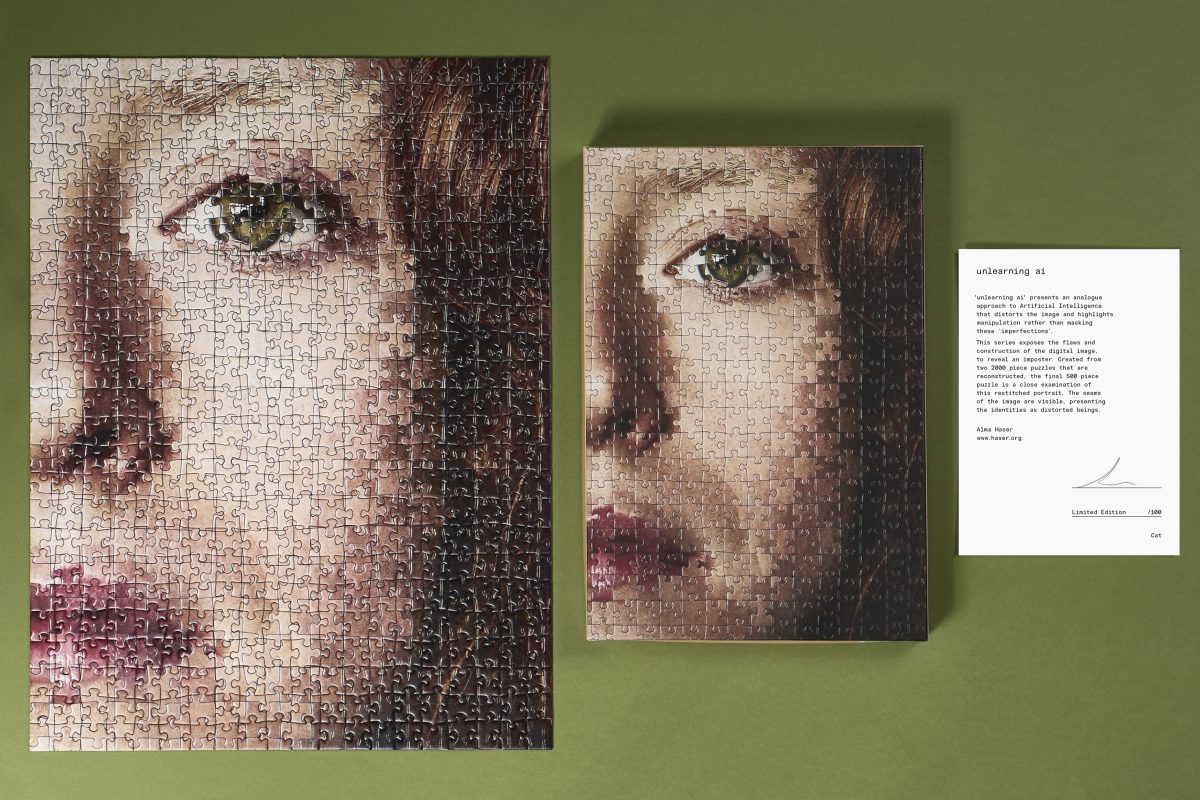

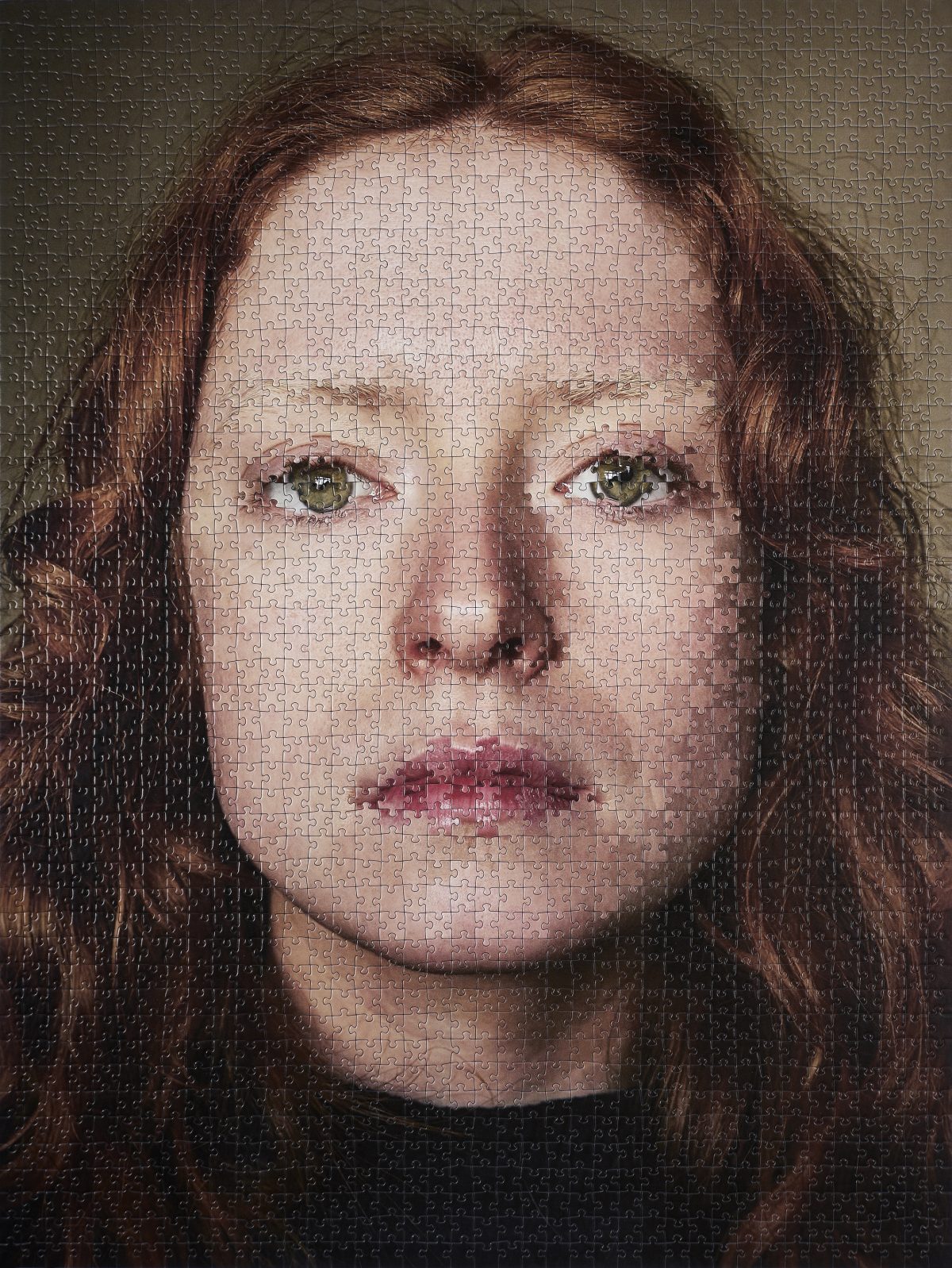

In Cat, the subject’s lips and eyes are fragmented, almost resembling a digital glitch — but it’s not. Every single choice that Haser makes is deliberate. It’s her hand that creates the traits of each subject. Utilizing puzzle pieces as a medium leans into the importance of detail and how every part of the puzzle is quite literally essential to make it a whole. Without a single piece, we’re left with a blank space and information missing. These glitches are minor; noticeable but intentional, still allowing our brains to read the figure as human, but just one with flaws.

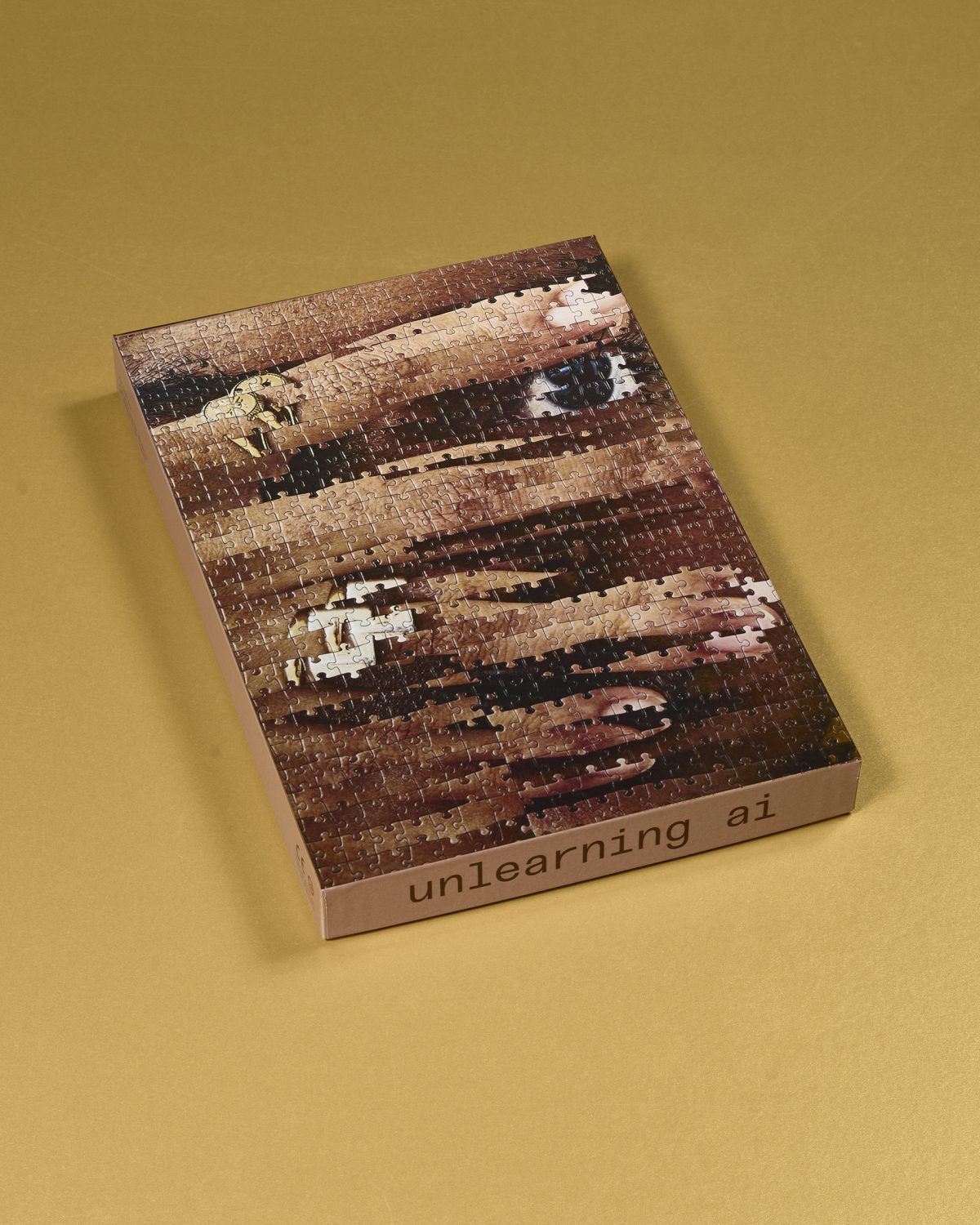

In a departure from the portraits, Hugo is figure-like but feels more representative of someone from another world. With eyes quadrupling, gums and teeth spreading, and two-tone ears, Haser’s artistic hand is felt more heavily. Still, she offers us symmetry, soothing our minds and allowing us to read the figure more easily. In a typical AI generated image, uneasiness can come from our own stress in trying to distinguish whether the person shown is human. However, in Haser’s work, she doesn’t leave us guessing.

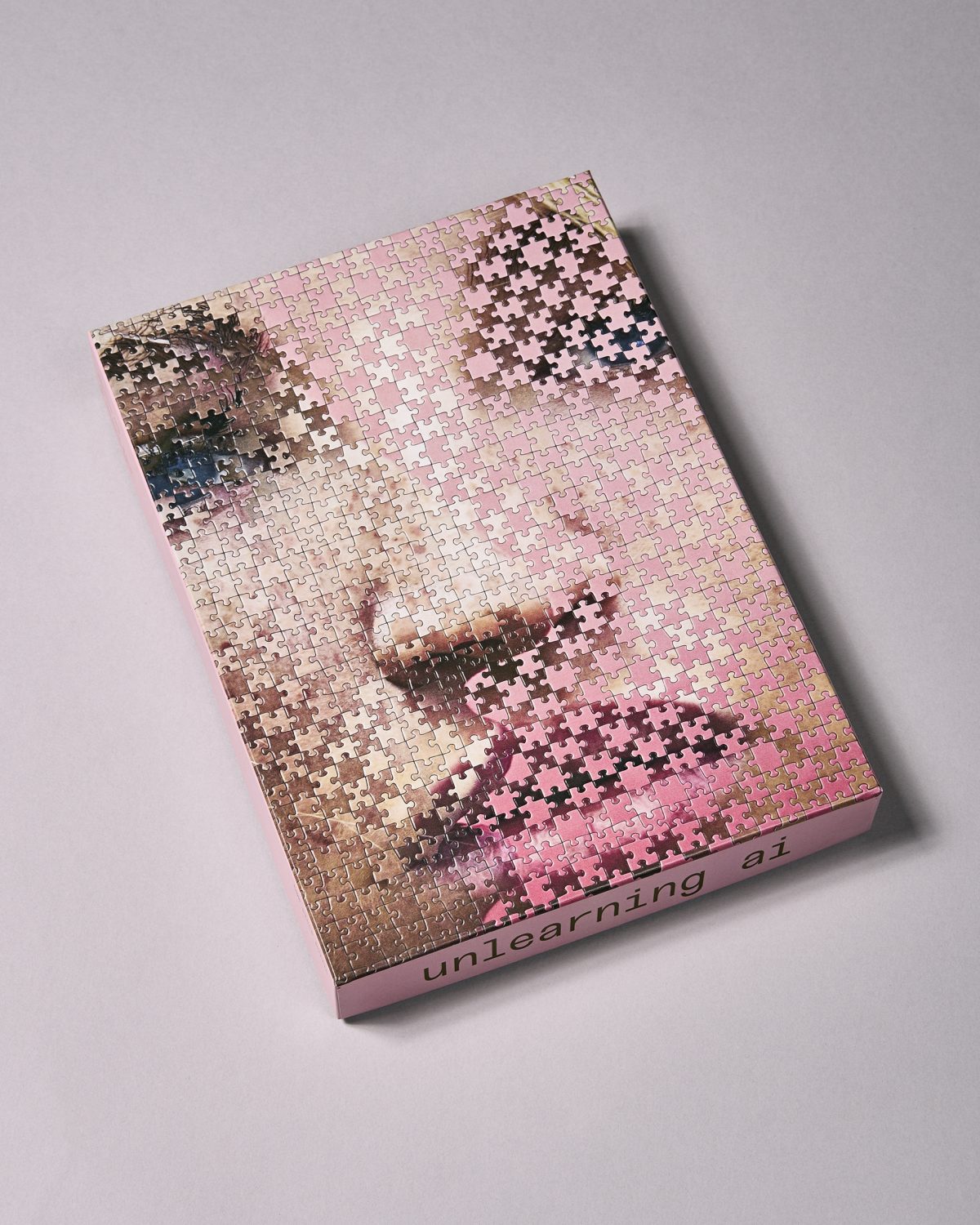

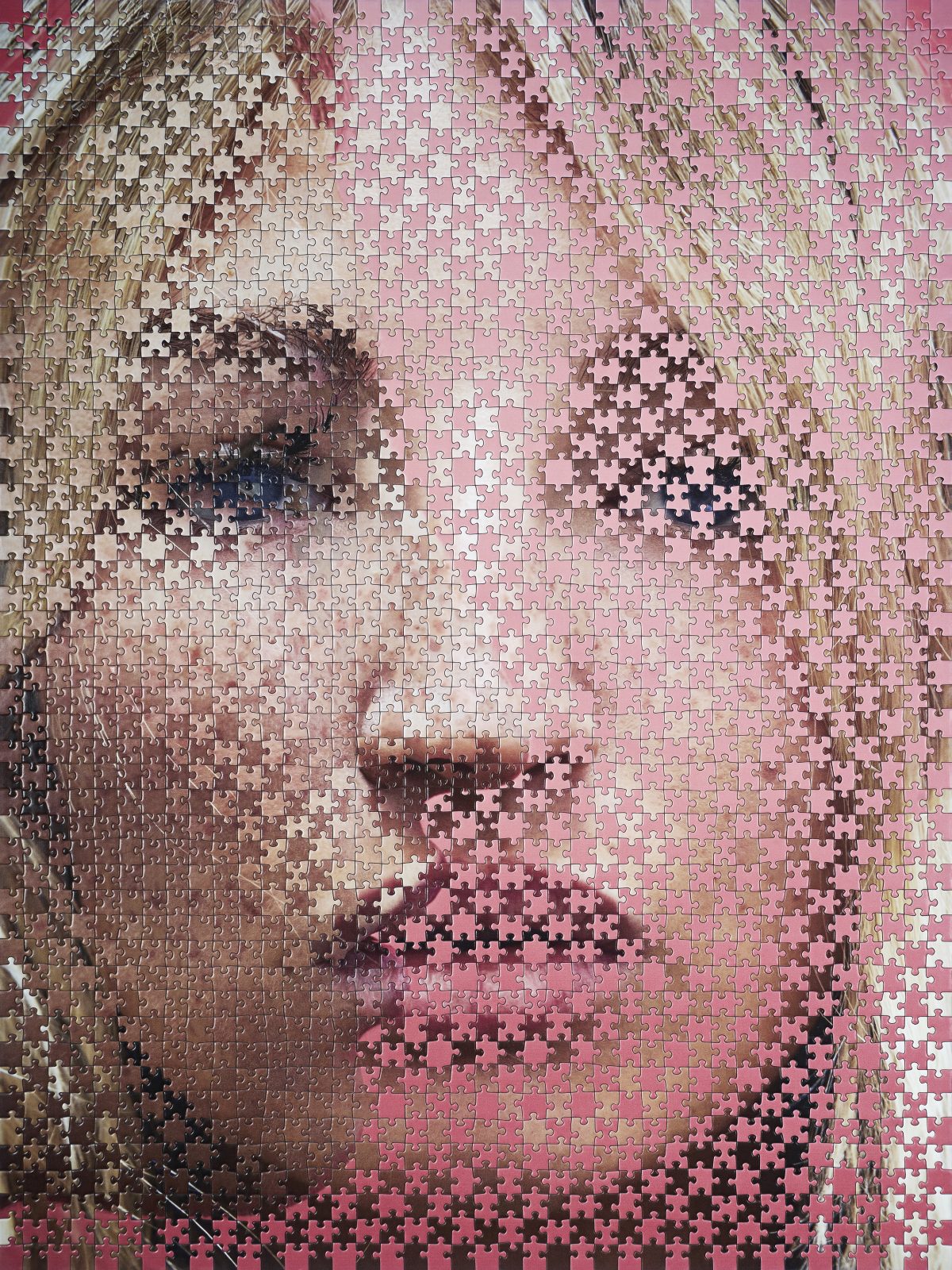

For an abstract approach in an image like Fred, Haser adds more color, weaving bright pinks into the figure’s skin, abstracting her features even more. We see peaks of blonde hair, fragments of a nose, and the slight curve of lips. Reminiscent of a wheatpaste poster buried in paint, only to weather off over time, Haser controls what the viewer can and cannot see, going out of her way to partially mask her images. In this space, we’re given breadcrumbs leaving some pieces, or sometimes all, to the imagination.

Adding another level of interaction to the series, Haser allows people to purchase the puzzles and attempt to make these collages in their own home. However, she added another challenge by photographing the final puzzle artwork and printing that onto another puzzle, showing the original lines on each piece. Haser said that although it was confusing, it was an obstacle that people enjoyed and offered a more affordable way of purchasing her artworks. Coincidentally, people have asked Haser to make work representing AI even though each of her pieces are made using the opposite technology. Her series is meant to examine it, not to utilize it. She says, “I wanted to see if I could make a series that would question AI, the speed at which it is learning, and the clean and finished feel of it–by stopping, slowing the process, and turning it back into a man-made object, not in any way aligned and full of imperfections.”

When looking at Unlearning AI, Haser is interested in going back to basics. She says that by connecting each portrait in the series, she hopes she’ll have created “an army of connected people.” She says, “Maybe [this work is] a play on how I hope technology will help us in the future if it is used correctly, or maybe even once we unlearn it all.” Haser allows herself to experiment; although inspired by AI, her own procedure is not one that can be duplicated by a machine. Her process, which is equally as important as the images, favors faults and defects over being ideal. Unlearning AI is a resistance, and in a culture that worships perfection, her images allow us to find peace in mistakes.

Angelina Ruiz is a Queer Puerto Rican artist and writer, based in New York City. Their work surrounds arts and culture at the intersection of gender, sexuality, and race.

Alma Haser is known for expanding the dimensions of traditional portrait photography through her use of inventive paper-folding techniques, collage and mixed media.